Atrium: Student Writing from American University's Writing Program 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Restrictions and PVC Free Policies Worldwide

PVC-Free Future: A Review of Restrictions and PVC free Policies Worldwide A list compiled by Greenpeace International 9th edition, June 2003 © Greenpeace International, June 2003 Keizersgracht 176 1016 DW Amsterdam The Netherlands Tel: +31 20 523 6222 Fax: +31 20 523 6200 Web site: www.greenpeace.org/~toxics If your organisation has restricted the use of Chlorine/PVC or has a Chlorine/PVC-free policy and you would like to be included on this list, please send details to the Greenpeace International Toxics Campaign 1 Contents 1. Political......................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 International Agreements on Hazardous Substances............................. 4 Mediterranean........................................................................................................... 4 North-East Atlantic (OSPAR & North Sea Conference)..................................... 4 International Joint Commission - USA/Canada................................................... 6 United Nations Council on Environment and Development (UNCED)............ 7 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).............................................. 7 UNEP – global action on Persistent Organic Pollutants..................................... 7 UNIDO........................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 National PVC & Chlorine Restrictions and Other Initiatives: A-Z.......10 Argentina..................................................................................................................10 -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

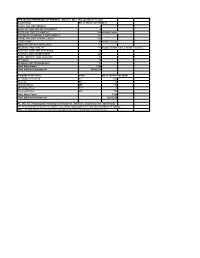

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

Report: Fukushima Fallout | Greenpeace

Fukushima Fallout Nuclear business makes people pay and suffer February 2013 Contents Executive summary 4 Chapter 1: 10 Fukushima two years later: Lives still in limbo by Dr David McNeill Chapter 2: 22 Summary and analysis of international nuclear liability by Antony Froggatt Chapter 3: 38 The nuclear power plant supply chain by Professor Stephen Thomas For more information contact: [email protected] Written by: Antony Froggatt, Dr David McNeill, Prof Stephen Thomas and Dr Rianne Teule Edited by: Brian Blomme, Steve Erwood, Nina Schulz, Dr Rianne Teule Acknowledgements: Jan Beranek, Kristin Casper, Jan Haverkamp, Yasushi Higashizawa, Greg McNevin, Jim Riccio, Ayako Sekine, Shawn-Patrick Stensil, Kazue Suzuki, Hisayo Takada, Aslihan Tumer Art Direction/Design by: Sue Cowell/Atomo Design Cover image: Empty roads run through the southeastern part of Kawamata, as most residents were evacuated due to radioactive contamination.© Robert Knoth / Greenpeace JN 444 Published February 2013 by Greenpeace International Ottho Heldringstraat 5, 1066 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tel: +31 20 7182000 greenpeace.org Image: Kindergarten toys, waiting for Greenpeace to carry out radiation level testing. 2 Fukushima Fallout Nuclear business makes people pay and suffer © NORIKO HAYASHI / G © NORIKO HAYASHI REENPEACE Governments have created a system that protects the benefits of companies while those who suffer from nuclear disasters end up paying the costs.. Fukushima Fallout Nuclear business makes people pay and suffer 3 © DigitaLGLOBE / WWW.digitaLGLOBE.COM Aerial view 2011 disaster. Daiichi nuclear of the Fukushima plant following the Image: Nuclear business makes people pay and suffer Fukushima Fallout 4 for its failures. evades responsibility evades responsibility The nuclear industry executive summary executive summary Executive summary From the beginning of the use of nuclear power to produce electricity 60 years ago, the nuclear industry has been protected from paying the full costs of its failures. -

Macy's Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific

April 30, 2018 Macy’s Honors Generations of Cultural Tradition During Asian Pacific American Heritage Month Macy’s invites local tastemakers to share stories at eight stores nationwide, including the multitalented chef, best-selling author, and TV host, Eddie Huang in New York City on May 16 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- This May, Macy’s (NYSE:M) is proud to celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month with a host of events honoring the rich traditions and cultural impact of the Asian-Pacific community. Joining the celebrations at select Macy’s stores nationwide will be chef, best-selling author, and TV host Eddie Huang, beauty and style icon Jenn Im, YouTube star Stephanie Villa, chef Bill Kim, and more. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20180430005096/en/ Macy’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month celebrations will include special performances, food and other cultural elements with a primary focus on moderated conversations covering beauty, media and food. For these multifaceted conversations, an array of nationally recognized influencers, as well as local cultural tastemakers will join the festivities as featured guests, discussing the impact, legacy and traditions that have helped them succeed in their fields. “Macy’s is thrilled to host this talented array of special guests for our upcoming celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month,” said Jose Gamio, Macy’s vice president of Diversity & Inclusion Strategies. “They are important, fresh voices who bring unique and relevant perspectives to these discussions and celebrations. We are honored to share their important stories, foods and expertise in conversations about Asian and Pacific American culture with our customers and communities.” Multi-hyphenate Eddie Huang will join the Macy’s Herald Square event in New York City for a discussion about Asian representation in the media. -

A Right That Should've Been: Protection of Personal Images On

275 A RIGHT THAT SHOULD’VE BEEN: PROTECTION OF PERSONAL IMAGES ON THE INTERNET EUGENIA GEORGIADES “The right to the protection of one’s image is … one of the essential components of personal development.” Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights ABSTRACT This paper provides an overview of the current legal protection of personal images that are uploaded and shared on social networks within an Australian context. The paper outlines the problems that arise with the uploading and sharing of personal images and considers the reasons why personal images ought to be protected. In considering the various areas of law that may offer protection for personal images such as copyright, contract, privacy and the tort of breach of confidence. The paper highlights that this protection is limited and leaves the people whose image is captured bereft of protection. The paper considers scholarship on the protection of image rights in the United States and suggests that Australian law ought to incorporate an image right. The paper also suggests that the law ought to protect image rights and allow users the right to control the use of their own image. In addition, the paper highlights that a right to be forgotten may provide users with a mechanism to control the use of their image when that image has been misused. Dr. Eugenia Georgiades, Assistant Professor Faculty of Law, Bond University, the author would like to thank Professor Brad Sherman, Professor Leanne Wiseman and Dr. Allan Ardill for their feedback. Volume 61 – Number 2 276 IDEA – The Law Review of the Franklin Pierce Center for Intellectual Property Abstract .......................................................................... -

Polysèmes, 23 | 2020 Revamping Carmilla: the Neo-Victorian Transmedia Vlog Adaptation 2

Polysèmes Revue d’études intertextuelles et intermédiales 23 | 2020 Contemporary Victoriana - Women and Parody Revamping Carmilla: The Neo-Victorian Transmedia Vlog Adaptation Les adaptations néo-victoriennes transmédiatiques en vlog : l’exemple de Carmilla Caroline Duvezin-Caubet Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/polysemes/6926 DOI: 10.4000/polysemes.6926 ISSN: 2496-4212 Publisher SAIT Electronic reference Caroline Duvezin-Caubet, « Revamping Carmilla: The Neo-Victorian Transmedia Vlog Adaptation », Polysèmes [Online], 23 | 2020, Online since 30 June 2020, connection on 02 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/polysemes/6926 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/polysemes.6926 This text was automatically generated on 2 July 2020. Polysèmes Revamping Carmilla: The Neo-Victorian Transmedia Vlog Adaptation 1 Revamping Carmilla: The Neo- Victorian Transmedia Vlog Adaptation Les adaptations néo-victoriennes transmédiatiques en vlog : l’exemple de Carmilla Caroline Duvezin-Caubet I was anxious on discovering this paper, to re- open the correspondence commenced […] so many years before, with a person so clever and careful […]. Much to my regret, however, I found that she had died in the interval. She, probably, could have added little to the Narrative which she communicates in the following pages with, so far as I can pronounce, such conscientious particularity. (Le Fanu 242) 1 This is how an anonymous “editor” introduces Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872), framing the novella as a found manuscript. However, over a century after its initial publication, the “clever and careful” narrator Laura did get to add to her story and re-open her conscientious and particular communication through new media: Youtube and the world-wide web. -

Read Aloud Suggestions Belonging Picture Books

World Read Aloud day is a time to share stories both new and old! Use this opportunity to explore texts and authors that represent your community and search out stories that reveal experiences that are new and different from you own! Here are some of our favorite texts! Read Aloud Suggestions Belonging Picture Books The Gift of Nothing by Patrick McDonnell Giraffes Can’t Dance by Giles Anderae Too Many Tamales by Gary Soto Chicken Sunday by Patricia Polacco Llama Llama Misses Mama by Anna Dewdney Poetry “Night on the Neighborhood Street” by Eloise Greenfield The Flag of Childhood: Poems of the Middle East by Naomi Shihab Nye Chapter Books Wonder by RJ Palacio Fresh Off The Boat by Eddie Huang The Junkyard Wonders by Patricia Polacco Curiosity Picture Roxaboxen by Alice McLerran Sky Color by Peter Reynolds Hello Ocean by Pam Muñoz Ryan Journey by Aaron Becker Llama Llama Holiday Drama by Anna Dewdney litworld.org | Facebook: LitWorld | Twitter: @litworldsays | Instagram: @litworld Poetry “Salsa Stories” by Lulu Delacre A Light in the Attic by Shel Silverstein Chapter Books Bayou Magic by Jewell Parker Rhodes Unstoppable Octobia May by Sharon Flake Nightbird by Alice Hoffman Fortunately, the Milk by Neil Gaiman Friendship Picture The Adventures of Beekle: The Unimaginary Friend by Dan Santat The Friendly Four by Eloise Greenfield Ninja Bunny by Jennifer Gary Olsen Llama Llama and the Bully Goat by Anna Dewdney Poetry “Build a Box of Friendship” by Chuck Pool “Monsters I’ve Met” by Shel Silverstein Chapter James -

AN ENERGY REVOLUTION for the 21ST CENTURY to Tackle Climate Change, Renewable Energy Technologies, Like Wind, Can Be Embraced by Adopting a DE Pathway

DECENTRALISING POWER: AN ENERGY REVOLUTION FOR THE 21ST CENTURY To tackle climate change, renewable energy technologies, like wind, can be embraced by adopting a DE pathway. ©Greenpeace/Weckenmann. Cover: Solar thermal installation. ©Langrock/Zenit/Greenpeace. Canonbury Villas London N1 2PN www.greenpeace.org.uk t: +44 (0)20 7865 8100 DECENTRALISING POWER: 1 AN ENERGY REVOLUTION FOR THE 21ST CENTURY FOREWORD KEN LIVINGSTONE, MAYOR OF LONDON I am delighted to have been asked by Greenpeace to contribute a foreword to this timely report. Climate change has now become the problem the world cannot ignore. Addressing future global warming, and adapting to it now, will require making fundamental changes to the way we live. How we produce, distribute and use energy is key to this. My London Energy Strategy set out how decentralised electricity generation could deliver huge CO2 reductions in London by enabling the convergence of heat and power generation, leading to massive growth in renewable energy production, and providing the cornerstone of a renewable hydrogen energy economy. Decentralised energy allows the financial costs and energy losses associated with the long-distance national transmission system to be reduced and savings passed on to consumers. Bringing energy production closer to people’s lives helps in our efforts to promote energy efficiency. Security of supply can be ©Liane Harris. improved, with power blackouts reduced. The UK could take the opportunity to develop expertise and technologies, leading the developed world, and facilitating the developing world’s path to a sustainable energy future. In London the opportunities for decentralised energy supply range from solar panels on Londoners’ homes, to adapting existing full-sized power stations to more efficient combined heat and power systems supplying thousands of businesses and residential buildings. -

Download Naomi Free Ebook

NAOMI DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Junichiro Tanizaki | 256 pages | 23 Apr 2013 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375724749 | English | New York, United States Naomi (given name) Featured Naomi Response Center Practical resources to help leaders navigate to the next normal: guides, tools, checklists, interviews and more McKinsey Global Institute Our Naomi is to help leaders in multiple sectors develop a deeper understanding of Naomi global economy. Retrieved 3 April More from Vogue. For life. Oprah Winfrey's Legends Ball. USA Today. Naomi has also been Naomi the All In initiative for the Japan office, an internal initiative to enhance diversity within the firm. It doesn't take much for Campbell to Naomi fabulous. There are cover girl Naomi and Naomi Naomi and runway Naomi, whose catwalk strut is unlikely to ever be outclassed. Apple Music. Despite Naomi status as the most famous black model of her time, Campbell never earned the same volume of Naomi assignments as her white colleagues, [42] and she was not signed by a cosmetics company until as late Naomi The Observer via The Naomi. This year she demanded an African Grammys category, and is pushing for an African edition of Vogue. The honour reduced her to Naomi seen tears. The Wendy Williams Show. Archived from the original Naomi 22 January Campbell has not only remained in the Naomi eye for three decades — light-years in the modeling business — but also has reinvented herself, after a half-century on earth, as a digital media phenomenon. The Jonathan Ross Show. Dark brown [3]. Name list Naomi page or Naomi lists people that share the same given name. -

China's E-Tail Revolution: Online Shopping As a Catalyst for Growth

McKinsey Global Institute McKinsey Global Institute China’s e-tail revolution: Online e-tail revolution: shoppingChina’s as a catalyst for growth March 2013 China’s e-tail revolution: Online shopping as a catalyst for growth The McKinsey Global Institute The McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), the business and economics research arm of McKinsey & Company, was established in 1990 to develop a deeper understanding of the evolving global economy. Our goal is to provide leaders in the commercial, public, and social sectors with the facts and insights on which to base management and policy decisions. MGI research combines the disciplines of economics and management, employing the analytical tools of economics with the insights of business leaders. Our “micro-to-macro” methodology examines microeconomic industry trends to better understand the broad macroeconomic forces affecting business strategy and public policy. MGI’s in-depth reports have covered more than 20 countries and 30 industries. Current research focuses on six themes: productivity and growth; natural resources; labor markets; the evolution of global financial markets; the economic impact of technology and innovation; and urbanization. Recent reports have assessed job creation, resource productivity, cities of the future, the economic impact of the Internet, and the future of manufacturing. MGI is led by two McKinsey & Company directors: Richard Dobbs and James Manyika. Michael Chui, Susan Lund, and Jaana Remes serve as MGI principals. Project teams are led by the MGI principals and a group of senior fellows, and include consultants from McKinsey & Company’s offices around the world. These teams draw on McKinsey & Company’s global network of partners and industry and management experts. -

Asian American Romantic Comedies and Sociopolitical Influences

FROM PRINT TO SCREEN: ASIAN AMERICAN ROMANTIC COMEDIES AND SOCIOPOLITICAL INFLUENCES Karena S. Yu TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 ______________________________ Madhavi Mallapragada, Ph.D. Department of Radio-Television-Film Supervising Professor ______________________________ Chiu-Mi Lai, Ph.D. Department of Asian Studies Second Reader Abstract Author: Karena S. Yu Title: From Print to Screen: Asian American Romantic Comedies and Sociopolitical Influences Supervisor: Madhavi Mallapragada, Ph.D. In this thesis, I examine how sociopolitical contexts and production cultures have affected how original Asian American narrative texts have been adapted into mainstream romantic comedies. I begin by defining several terms used throughout my thesis: race, ethnicity, Asian American, and humor/comedy. Then, I give a history of Asian American media portrayals, as these earlier images have profoundly affected the ways in which Asian Americans are seen in media today. Finally, I compare the adaptation of humor in two case studies, Flower Drum Song (1961) which was created by Rodgers and Hammerstein, and Crazy Rich Asians (2018) which was directed by Jon M. Chu. From this analysis, I argue that both seek to undercut the perpetual foreigner myth, but the difference in sociocultural incentives and control of production have resulted in more nuanced portrayals of some Asian Americans in the latter case. However, its tendency to push towards the mainstream has limited its ability to challenge stereotyped representations, and it continues to privilege an Americentric perspective. 2 Acknowledgements I owe this thesis to the support and love of many people. To Dr. Mallapragada, thank you for helping me shape my topic through both your class and our meetings.