A Chinese Bite of Translation: a Translational Approach to Chineseness and Culinary Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

As One of China's Most Celebrated Literary

BAS-RELIEFS A pair of Tang Dynasty (618-906 AD) dragon reliefs on the façade of the Kuo building greets passersby and diners. Margaret Kuo commissioned these reliefs to Lung-kuang Yang, a renowned sculptor from Hangchow, to honor the Chinese name of her new eatery on the Main Line, which translates into English as the “Dragon’s Lair.” She chose the simple majesty of an ancient version of a Tang dragon devoid of modern embellishment to memorialize one of the Golden Ages of Chinese culture, known for its literature and arts. Continuing with this theme, the bas-reliefs of horses on the wall of the first floor dining room are sculpted replicas of two of six reliefs ordered by Emperor Tai-tsung, founder of the Tang Dynasty. These figures portray favorite mounts that Tai-tsung rode into battle to secure his rule and the empire’s borders. The priceless originals are part of the collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, in Philadelphia. POEM by LI PO As one of China’s most celebrated literary legends, Li Po’s poem is both spontaneous and inspiring. His life (701-762 AD) and works epitomize the adventuresome splendor of the Tang Dynasty with its military prowess romanticized and tempered by art, music and literature. Margaret Kuo selected the following verses by this extraordinary Tang Dynasty poet to adorn her dining room in the form of carved calligraphy flanking the horse bas-reliefs. The translation by Simon Elegant reads as follows: A pot of wine amidst the flowers’ With these two I set alone, no friends to drink with Or waste this Spring evening. -

Jamie Kennedy

Jamie Kennedy One of Canada’s most celebrated chefs, Jamie Kennedy is known for his legendary commitment to environmental issues and his support for organic agriculture, local producers and traditional methods. This translates into choices about the fish we buy, the meat and vegetables we serve and increasingly the wines we choose to offer. Jamie makes every effort to minimize the impact of our operations on the environment and we are continuously on the look out for like-minded suppliers and better methods of work. His respect for traditional practices exerted its influence early on in Jamie Kennedy’s culinary endeavors, precipitating his decision to pursue an apprenticeship. Over the course of three years, Jamie worked for one Chef, under whose tutelage he learned basic kitchen skills, including how to manage staff and strike a balance between life and the demands of being a Chef. Having graduated from the apprenticeship program at George Brown in 1977, Jamie finessed his training and experience as Journeyman Cook in Europe from 1977 to 1979. In this ever- evolving learning environment, Jamie experienced what he describes as “a gradual awakening to gastronomy”. The Restaurants of Jamie Kennedy Returning to Toronto, Jamie opened what is now one of Toronto’s most renowned and respected restaurants, Scaramouche. Modeled on the French three-star system, Scaramouche was heralded as a new phase in Canadian culinary history and solidified Jamie’s reputation as a pioneer of contemporary Canadian cuisine. However, it was not until 1985 when he opened Palmerston Restaurant and established relationships with a number of local artisan producers that Jamie began to identify and develop what would become his own definitive style. -

Appetizers Soups Fried Rice Egg Foo Young Chop Suey

Appetizers Chop Suey (w/Rice) Chinese Specialties (Full Size, w/Steam Rice and Hot Roll) Egg Rolls . 1.35 Poultry Chow Mein (w/Hard Noodles) , Szechuan Spicy Beef . 11.75 Spring Roll (veg. only) . 1.75 Almond Chicken . 10.25 Small Large Crab Regoon (4) . 3.75 (8) . 6.50 Sweet & Sour Chicken . 10.25 , Mongolian Beef . 11.75 Pork Shredded beef stir-fried with scallions. Fried Wontons, (12) Plain . 3.75 Extra Fine ......... 5.25 9.25 Gai Kew . 10.25 Fried Wontons, (8) w/Meat . 5.75 Chicken stir-fried w/Chinese veg. Mushroom ...... 5.75 9.95 Moo Goo Gai Pan . 10.75 Pot Stickers -= pork =- (8) . 6.65 Subgum ........... 5.75 9.95 Mandarin Chicken . 11.75 Pot Stickers -= chicken =- (8) . 6.65 Chicken ............... 5.25 9.25 Breaded chicken stuffed w/ham in sweet & sour sauce. Pork Char Shu Bow . 3.25 Hong Shu Gai . 10.25 Sweet & Sour Pork . 10.25 Mushroom ....... 5.75 9.95 Breaded chicken stir-fried w/Chinese veg. Bar-B-Q Pork . (small) 5.50 (large) 9.75 Char Shu Kew . 10.25 Subgum ............ 5.75 9.95 Sesame Chicken (old style) . 10.50 Breaded chicken served w/a rich brown gravy. Roast pork served w/Chinese vegetables. Beef ................... 5.60 9.95 Sesame Chicken (new style) . 10.95 Moo Goo Chow Yok . 10.75 Soups Mushroom ........ 6.25 10.25 Lightly breaded chicken with a sweet taste. Extra fine cut pork w/mushrooms in a garlic Small Large Subgum ........... 6.25 10.25 Chicken with Broccoli . 10.25 and black bean sauce. -

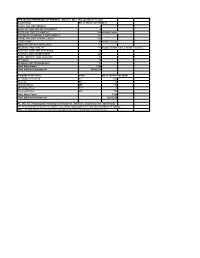

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 Through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No

NPR ISSUES/PROGRAMS (IP REPORT) - March 1, 2021 through March 31, 2021 Subject Key No. of Stories per Subject AGING AND RETIREMENT 5 AGRICULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT 76 ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT 149 includes Sports BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND FINANCE 103 CRIME AND LAW ENFORCEMENT 168 EDUCATION 42 includes College IMMIGRATION AND REFUGEES 51 MEDICINE AND HEALTH 171 includes Health Care & Health Insurance MILITARY, WAR AND VETERANS 26 POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT 425 RACE, IDENTITY AND CULTURE 85 RELIGION 19 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 79 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 Program Codes (Pro) Code No. of Stories per Show All Things Considered AT 645 Fresh Air FA 41 Morning Edition ME 513 TED Radio Hour TED 9 Weekend Edition WE 191 Total Story Count 1399 Total duration (hhh:mm:ss) 125:02:10 AT, ME, WE: newsmagazine featuring news headlines, interviews, produced pieces, and analysis FA: interviews with newsmakers, authors, journalists, and people in the arts and entertainment industry TED: excerpts and interviews with TED Talk speakers centered around a common theme Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Aging and Retirement ALL THINGS CONSIDERED 03/23/2021 0:04:22 Hit Hard By The Virus, Nursing Homes Are In An Even More Dire Staffing Situation Aging and Retirement WEEKEND EDITION SATURDAY 03/20/2021 0:03:18 Nursing Home Residents Have Mostly Received COVID-19 Vaccines, But What's Next? Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/15/2021 0:02:30 New Orleans Saints Quarterback Drew Brees Retires Aging and Retirement MORNING EDITION 03/12/2021 0:05:15 -

Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago During the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Summer 2019 Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 Samuel C. King Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Recommended Citation King, S. C.(2019). Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5418 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exclusive Dining: Immigration and Restaurants in Chicago during the Era of Chinese Exclusion, 1893-1933 by Samuel C. King Bachelor of Arts New York University, 2012 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Lauren Sklaroff, Major Professor Mark Smith, Committee Member David S. Shields, Committee Member Erica J. Peters, Committee Member Yulian Wu, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Abstract The central aim of this project is to describe and explicate the process by which the status of Chinese restaurants in the United States underwent a dramatic and complete reversal in American consumer culture between the 1890s and the 1930s. In pursuit of this aim, this research demonstrates the connection that historically existed between restaurants, race, immigration, and foreign affairs during the Chinese Exclusion era. -

Rural Memory and Rural Development

Rural Memory and Rural Development by Xinran Tang Submitted in partial fulflment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2019 © Copyright by Xinran Tang, 2019 CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ........................................................................................... v Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 Thesis Questions ................................................................................. 2 1.2 Rural China .......................................................................................... 2 1.3 History of Rural China .......................................................................... 3 1.4 Chinese Rural Society .......................................................................... 4 1.5 Challenges and Problems in Rural China ............................................ 5 1.6 The Relationship Between City and Rural Area ................................... 8 1.7 Opportunities for Rural China ............................................................... 10 1.8 Site: Liujiadu Village ............................................................................. 11 Chapter 2: Rural Memory Study ........................................................................ 14 2.1 Collective Memory ............................................................................... -

Culinary Chronicles

Culinary Chronicles THE NEWSLETTER OF THE CULINARY HISTORIANS OF ONTARIO SUMMER 2010 NUMBER 65 Marie Nightingale’s classic cookbook, Old of Old Nova Scotia Kitchens, will enjoy a fortieth anniversary reprinting in October by Nimbus Publishing in Halifax. Included will be a new introduction from Marie, some new recipes, and a forward from Chef Michael Howell of Tempest Restaurant in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. Marie and Michael both contribute to this issue of Culinary Chronicles too. The original hard cover edition of 1970 will be replicated for the fortieth anniversary edition. (Image courtesy of Nimbus Publishing) Cover of the ninth printing, August 1976, with drawings by Morna MacLennan Anderson. (Image courtesy of Fiona Lucas) _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Contents President’s Message 2 CHO Members News 10 Newsletter News 2 Tribute: Margo Oliver Morgan, It’s Only Too Late If You Don’t Start 1923–2010 Helen Hatton 11–13 Now: A Profile of Marie Nightingale Book Reviews: Mary Elizabeth Stewart 3, 10 Atlantic Seafood Janet Kronick 14 Celebrating the Fortieth Anniversary The Edible City Karen Burson 15 Of Marie Nightingale’s Out of Old CHO Program Reviews: Nova Scotia Kitchens Michael Howell 4–5 Talking Food Janet Kronick 16, 19 260 Years of the Halifax Farmers Apron-Mania Amy Scott 17 Market Marie Nightingale 6–7 Two Resources for Canadian Culinary Dean Tudor’s Book Review: South History: Shore Tastes 7 Back Issues of Culinary Chronicles Speaking of Food, No. 1: Bakeapples A Selected Bibliography 18 and Brewis in Newfoundland CHO Upcoming Events 19 Gary Draper 8–9 About CHO 20 2 Culinary Chronicles _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ President’s Message Summer is a time for fresh local fruits and vegetables, farmers' markets, lazy patio meals, and picnics. -

“Steak, Blé D'inde, Patates”

SANDRA ROY “Steak, Blé d’Inde, Patates” Eating national identity in late twentieth-century Québec This paper explores the connections between pâté chinois and Québec national identity during the second half of the twentieth century. The respective French, British, and Native roots of the ingredients are highlighted and discussed, with a particular emphasis on socioeconomic and cultural terms that also extends to the analysis of the historical preparation of the layered meal, more akin to “daily survival” than to gastronomy. Special attention is also given to the significance of the dish’s origin myths, as well as to cultural references on a popular television series. Those origin myths are separated along the French/English divide, thus evoking the often- tempestuous relationship between these two languages and their speakers in Québec. The progression of the discourse surrounding pâté chinois, from a leftover dish prior to the rise of nationalism in the ’70s, to a media darling in the decade following the 1995 referendum, corresponds with efforts to define and then to redefine Québécois identity. The history of the dish tells the tumultuous history of the people of Québec, their quest for a unique identity, and the ambiguous relationship they have with language. Pâté chinois became a symbol, reminding French Canadians of Québec daily of their Québécois identity. Keywords: pâté chinois, food, Québec, national identity, La Petite Vie (TV series), French language INTRODUCTION As a little girl, pâté chinois was my favourite meal—but only my grandmother’s version. The classic recipe is simple: cooked ground beef at the bottom, canned corn—blé d’Inde—in the middle, mashed potatoes on top, warmed in the oven for a few minutes.1 Grandma did it differently: she mixed all the ingredients together without putting them in the oven. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Xi Tian August 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson Dr. Paul Pickowicz Dr. Yenna Wu Copyright by Xi Tian 2014 The Dissertation of Xi Tian is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 by Xi Tian Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Comparative Literature University of California, Riverside, August 2014 Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson My dissertation rethinks satire and redefines our understanding of it through the examination of works from the 1930s and 1940s. I argue that the fluidity of satiric writing in the 1930s and 1940s undermines the certainties of the “satiric triangle” and gives rise to what I call, variously, self-satire, self-counteractive satire, empathetic satire and ambiguous satire. It has been standard in the study of satire to assume fixed and fairly stable relations among satirist, reader, and satirized object. This “satiric triangle” highlights the opposition of satirist and satirized object and has generally assumed an alignment by the reader with the satirist and the satirist’s judgments of the satirized object. Literary critics and theorists have usually shared these assumptions about the basis of satire. I argue, however, that beginning with late-Qing exposé fiction, satire in modern Chinese literature has shown an unprecedented uncertainty and fluidity in the relations among satirist, reader and satirized object. -

©Catherine Turgeon-Gouin 2011

THE MYTH OF QUÉBEC’S TRADITIONAL CUISINE CATHERINE TURGEON-GOUIN, ENGLISH LITERATURE MCGILL UNIVERSITY, MONTREAL A THESIS SUBMITTED TO MCGILL UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE MASTERS DEGREE OF ENGLISH LITERATURE ©Catherine Turgeon-Gouin 2011 Table of Contents ABSTRACT 3 RÉSUMÉ 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 5 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER 1 21 1: ELECTING A NATIONAL MEAL 21 1.2: FOOD AS NATIONAL SYMBOL 22 SECTION 1.3: HOW FOOD CARRIES MEANING 23 SECTION 2: A PROVISIONAL CANON OF TRADITIONAL QUÉBEC DISHES 24 2.2: NATIONALIZATION PROCESS 28 2.3: FROM NATIONAL PRODUCT TO NATIONAL SYMBOL 33 CONCLUSION 39 CHAPTER 2 40 PART 1 40 SECTION 1 - EXPLAINING THE BASIC STRUCTURE OF BARTHES’ NOTION OF MYTH 44 SECTION 2 - EXAMPLE AND TERMINOLOGY 45 PART 2 50 SECTION 1 - AU PIED DE COCHON AS MYTH 50 SECTION 2 – INGREDIENTS 54 SECTION 3 – MENU 61 SECTION 4: FAMILIAL, CONVIVIAL ATMOSPHERE 66 CONCLUSION 72 CHAPTER 3 74 PART 1: MAKING A MYTHOLOGY OF MYTH – THE THEORY 76 PART 2: O QUÉBEC RESTAURANTS AS MYTHOLOGY 80 2.1 ROOTED IN THE MYTH OF QUÉBEC’S TRADITIONAL CUISINE 80 2.2 – THE ‘ORNAMENTED’ AND ‘SUBJUNCTIVE’ FORM: THE DISNEY INFLUENCE 86 2.3 THE CONCEPT: THE GAZE AND THE STAGE 92 2.4 THE FINAL SIGNIFICATION: MYTH UNCOVERED BY MYTHOLOGY 95 CONCLUSION 98 WORKS CITED 104 2 Abstract Ever since Brillat-Savarin famously claimed that “we are what we eat,” thinkers and critics have tried, in this generation more than ever, to articulate what, precisely, can be observed about identities through culinary practices. Nowhere is the relationship between identity and foodways as explicit as in a nation’s traditional cuisine.