QSNTS Native Title Handbook a Word from the CEO Welcome to the QSNTS Native Title Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulse March 2020

South West Hospital and Health Service Getting ready for Harmony Week 2020 from Cunnamulla were (clockwise from left) Tina Jackson, Deirdre Williams, Kylie McKellar, Jonathan Mullins, Rachel Hammond Please note: This photo was taken before implementation of social distancing measures. PULSE MARCH 2020 EDITION From the Board Chair Jim McGowan AM 5 From the Chief Executive, Linda Patat 6 OUR COMMUNITIES All in this together - COVID-19 7 Roma CAN supports the local community in the fight against COVID-19 10 Flood waters won’t stop us 11 Everybody belongs, Harmony Week celebrated across the South West 12 Close the Gap, our health, our voice, our choice 13 HOPE supports Adrian Vowles Cup 14 Voices of the lived experience part of mental health forum 15 Taking a stand against domestic violence 16 Elder Annie Collins celebrates a special milestone 17 Shaving success in Mitchell 17 Teaching our kids about good hygiene 18 Students learn about healthy lunch boxes at Injune State School 18 OUR TEAMS Stay Connected across the South West 19 Let’s get physical, be active, be healthy 20 Quilpie staff loving the South West 21 Don’t forget to get the ‘flu’ shot 22 Sustainable development goals 24 Protecting and promoting Human Rights 25 Preceptor program triumphs in the South West 26 Practical Obstetric Multi Professional Training (PROMPT) workshop goes virtual 27 OUR SERVICES Paving the way for the next generation of rural health professionals 28 A focus on our ‘Frail Older Persons’ 29 South West Cardiac Services going from strength to strength 30 WQ Pathways Live! 30 SOUTH WEST SPIRIT AWARD 31 ROMA HOSPITAL BUILD UPDATE 32 We would like to pay our respects to the traditional owners of the lands across the South West. -

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

Southern and Western Queensland Region

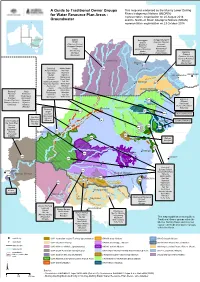

138°0'E 140°0'E 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E 152°0'E 154°0'E DOO MADGE E S (! S ' ' 0 Gangalidda 0 ° QUD747/2018 ° 8 8 1 Waanyi People #2 & Garawa 1 (QC2018/004) People #2 Warrungnu [Warrungu] Girramay People Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for they have been recognised by the Federal Court process. databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at GE ORG E TO W N People #2 Girramay Gkuthaarn and (! People #2 (! CARDW EL L that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Kukatj People map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 CARPENTARIA Tagalaka Southern and WesternQ UD176/2T0o2p0ographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Ewamian People QUD882/2015 Gurambilbarra Wulguru2k0a1b5a. Mada Claim The applications shown on the map include: and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give People #3 GULF REGION Warrgamay People (QC2020/N00o2n) freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. -

Evolution of Rights to Self-Determinism of Aboriginal People: a Comparative Analysis of Land Rights Reforms in Australia Alex Sadler, Divya Gupta Bowdoin College

Indigenous Policy Journal Vol. XXIX, No. 3 (Winter 2019) Evolution of Rights to Self-Determinism of Aboriginal People: A Comparative Analysis of Land Rights Reforms in Australia Alex Sadler, Divya Gupta Bowdoin College Abstract Despite Australia’s ratification of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2009, Aboriginal peoples continue to face obstacles in exercising their inherent rights to self-determination and to free, prior and informed consent regarding the development of their traditional land. Recent decades have seen advancements in legislation and government-backed programming to support the recognition of Aboriginal peoples’ land rights; however, the current framework often fails to achieve meaningful outcomes for impacted communities. This paper provides an overview of Australia’s current legislative and programming efforts to secure Aboriginal peoples’ land rights, evaluating the benefits and downsides to each initiative from a rights- based perspective, with the aim of promoting productive discourse on pathways to protecting and implementing the rights enshrined in the UNDRIP. Introduction In 2009, Australia ratified the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), after being one of only four countries to vote against its adoption in 2007. In reversing its decision, Australia symbolically demonstrated its commitment to the global shift towards the recognition of indigenous peoples’ inherent rights, which as the Declaration outlines derive from “their political, economic and social structures and from their cultures, spiritual traditions, histories and philosophies.” (United Nations, 2008) Although the UNDRIP covers a range of rights, from culture and identity to employment and education, a core focus of the agreement is the right of indigenous peoples to determine the development of their people and traditional land according to their own needs and interests. -

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups For

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Th is m ap w as e nd orse d by th e Murray Low e r Darling Rive rs Ind ige nous Nations (MLDRIN) for Water Resource Plan Areas - re pre se ntative organisation on 20 August 2018 Groundwater and th e North e rn Basin Aboriginal Nations (NBAN) re pre se ntative organisation on 23 Octobe r 2018 Bidjara Barunggam Gunggari/Kungarri Budjiti Bidjara Guwamu (Kooma) Guwamu (Kooma) Bigambul Jarowair Gunggari/Kungarri Euahlayi Kambuwal Kunja Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Mandandanji Mandandanji Murrawarri Giabel Bigambul Mardigan Githabul Wakka Wakka Murrawarri Githabul Guwamu (Kooma) M Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a r a Kambuwal !(Charleville n o Ro!(ma Mandandanji a GW21 R i «¬ v Barkandji Mutthi Mutthi GW22 e ne R r i i «¬ am ver Barapa Barapa Nari Nari d on Bigambul Ngarabal C BRISBANE Budjiti Ngemba k r e Toowoomba )" e !( Euahlayi Ngiyampaa e v r er i ie Riv C oon Githabul Nyeri Nyeri R M e o r Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Tati Tati n o e i St George r !( v b GW19 i Guwamu (Kooma) Wadi Wadi a e P R «¬ Kambuwal Wailwan N o Wemba Wemba g Kunja e r r e !( Kwiambul Weki Weki r iv Goondiwindi a R Barkandji Kunja e GW18 Maljangapa Wiradjuri W n r on ¬ Bigambul e « Kwiambul l Maraura Yita Yita v a r i B ve Budjiti Maljangapa R i Murrawarri Yorta Yorta a R Euahlayi o n M Murrawarri g a a l rr GW15 c Bigambul Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngarabal u a int C N «¬!( yre Githabul R Guwamu (Kooma) Ngemba iv er Kambuwal Kambuwal Wailwan N MoreeG am w Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Wiradjuri o yd Barwon River i R ir R Kwiambul !(Bourke iv iv Barkandji e er GW13 C r GW14 Budjiti -

The Astronomy of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Peoples and Their Neighbours

The Astronomy of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Peoples and Their Neighbours By Robert Stevens Fuller A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts at Macquarie University for the degree of Master of Philosophy November 2014 © Robert Stevens Fuller i I certify that the work in this thesis entitled “The Astronomy of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi Peoples and Their Neighbours” has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree to any other university or institution other than Macquarie University. I also certify that the thesis is an original piece of research and it has been written by me. Any help and assistance that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been appropriately acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. The research presented in this thesis was approved by Macquarie University Ethics Review Committee reference number 5201200462 on 27 June 2012. Robert S. Fuller (42916135) ii This page left intentionally blank Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................... iii Dedication ................................................................................................................................ vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... ix Publications .............................................................................................................................. -

A Thesis Submitted by Dale Wayne Kerwin for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy 2020

SOUTHWARD MOVEMENT OF WATER – THE WATER WAYS A thesis submitted by Dale Wayne Kerwin For the award of Doctor of Philosophy 2020 Abstract This thesis explores the acculturation of the Australian landscape by the First Nations people of Australia who named it, mapped it and used tangible and intangible material property in designing their laws and lore to manage the environment. This is taught through song, dance, stories, and paintings. Through the tangible and intangible knowledge there is acknowledgement of the First Nations people’s knowledge of the water flows and rivers from Carpentaria to Goolwa in South Australia as a cultural continuum and passed onto younger generations by Elders. This knowledge is remembered as storyways, songlines and trade routes along the waterways; these are mapped as a narrative through illustrations on scarred trees, the body, engravings on rocks, or earth geographical markers such as hills and physical features, and other natural features of flora and fauna in the First Nations cultural memory. The thesis also engages in a dialogical discourse about the paradigm of 'ecological arrogance' in Australian law for water and environmental management policies, whereby Aqua Nullius, Environmental Nullius and Economic Nullius is written into Australian laws. It further outlines how the anthropocentric value of nature as a resource and the accompanying humanistic technology provide what modern humans believe is the tool for managing ecosystems. In response, today there is a coming together of the First Nations people and the new Australians in a shared histories perspective, to highlight and ensure the protection of natural values to land and waterways which this thesis also explores. -

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 Letter of Transmittal

Queensland South Native Title Services ANNUAL REPORT 2014 - 2015 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Senator the Hon Nigel Scullion Minister for Indigenous Affairs Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 15 October 2015 Dear Minister, I am pleased to present the 2014 - 2015 Annual Report for Queensland South Native Title Services Limited (QSNTS). This report is provided in accordance with the Australian Government’s Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet 2013 - 2015 terms and conditions relating to the native title funding agreements under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), s203FE(1). The report includes independently audited financial statements for the financial year ending 30 June 2015. Thank you for your ongoing support of the work QSNTS strives to achieve. Yours sincerely, Board of Directors, Queensland South Native Title Services Diamantina Developmental Road, south of Herbert Downs Annual Report 2014 – 2015 | i TABLE OF CONTENTS Lettter of Transmittal ..................................................................................................................................................i Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................................01 Glossary ...................................................................................................................................................................02 Contact Details.......................................................................................................................................................03 -

Kerwin 2006 01Thesis.Pdf (8.983Mb)

Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author Kerwin, Dale Wayne Published 2006 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1614 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366276 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Aboriginal Dreaming Tracks or Trading Paths: The Common Ways Author: Dale Kerwin Dip.Ed. P.G.App.Sci/Mus. M.Phil.FMC Supervised by: Dr. Regina Ganter Dr. Fiona Paisley This dissertation was submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts at Griffith University. Date submitted: January 2006 The work in this study has never previously been submitted for a degree or diploma in any University and to the best of my knowledge and belief, this study contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the study itself. Signed Dated i Acknowledgements I dedicate this work to the memory of my Grandfather Charlie Leon, 20/06/1900– 1972 who took a group of Aboriginal dancers around the state of New South Wales in 1928 and donated half their gate takings to hospitals at each town they performed. Without the encouragement of the following people this thesis would not be possible. To Rosy Crisp, who fought her own battle with cancer and lost; she was my line manager while I was employed at (DATSIP) and was an inspiration to me. -

Sean Ulm, Anna Shnukal and Catherine Westcott

An Annotated Bibliography of Theses in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies at the University of Queensland, 1948–2000 Sean Ulm, Anna Shnukal and Catherine Westcott Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit Research Report Series Volume 5, 2001 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit Research Report Series Volume 5, 2001 Editors Editorial Advisory Committee Sean Ulm Cindy Shannon Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit School of Population Health University of Queensland University of Queensland Ian Lilley Jackie Huggins Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit University of Queensland University of Queensland Michael Williams Sam Watson Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit University of Queensland University of Queensland Copyright © 2001 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit The University of Queensland, Brisbane ISSN 1322–7157 ISBN 1864995939 The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit Research Report Series is an occasional refereed research report series published by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit at the University of Queensland. The main purpose of the Research Report Series is to disseminate the results of substantive research conducted by staff of the Unit, although manuscripts by other researchers dealing with contemporary issues in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies will be considered by the Editors. The views expressed in the Research Report Series are those of the author/s, and are not necessarily those of the Editors unless otherwise noted. All correspondence and submissions should be addressed to The Editors, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit Research Report Series, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Unit, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia, 4072. -

Handbook of Ethnography

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Wellesley College Library http://www.archive.org/details/handbookofethnogOOIeyb PUBLISHED ON THE LOUIS STERN MEMORIAL FUND HANDBOOK OF ETHNOGRAPHY BY JAMES G. LEYBURN Assistant Professor of the Science of Society in Yale University NEW HAVEN YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON . HUMPHREY MILFORD • OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1931 Copyright 1931 by Yale University Press Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. This book may not be re- produced, in whole or in part, in any form, ex- cept by written permission from the publishers. n PREFACE In any science the study of simple factors aids in the comprehen- sion of the complex. Especially is this true in the study of human society, for modern phenomena are so complicated that they are all but incomprehensible except when viewed in the light of their evolution. Immediately upon his return to simpler societies, how- ever, the reader meets the names of peoples and tribes unfamiliar to him : he has but vague ideas as to the location of the Hottentots, the Veddahs, and the Yakuts ; yet the more deeply he pursues his studies, the more acutely he feels the needs of some vade mecum to tell him who these people are and where they live. This Handbook of Ethnography is designed not only for the trained ethnologist, who cannot be expected to retain in his mem- ory more than a fraction of the tribal names included herein, but for the students in allied fields—in anthropology, archaeology, the science of society (sociology), political science, and the like. -

Language Groups in Goondir Service Region

Language Groups in Goondir Service Region Goondir Health Service’s, service provision area covers from Warwick in the southeast, travelling west to Goondiwindi and St George, and then north to Yuleba, and then east to Kingaroy, and then back south to Warwick. Presently the National Native Title Tribunal has four (4) claims that covers the Goondir Health Services region: QC 99/04 Western Wakka Wakka People QG 99/05 Barunggam People QC 97/50 Mandandanji QC 91/06 Bigambul People The traditional boundaries that encompass the Goondir Health Services region were formed by many groupings of Aboriginal people. The custom of trading goods and ceremony, as well as the kinship ties between the various clans/ language groups allowed the members of the different groups to speak not only their own language, but they would also have been able to communicate with visitors to their district. The impact of early European exploration also had the effect of bringing other languages into their area. An example would be the practice by the early explorers of using Aborigines from the NSW’s Hunter Valley, and the Liverpool Plains district as guides, and they would have carried new languages and dialects into this region. The constant sharing of languages has led to present day confusion on what were the ‘traditional boundaries’ for the various clans/language groups. An example is Goondiwindi, as records show that it is situated within the boundaries of two (2) language groups, the Kamilaroi and the Bigambul. This confusion is evident in nearly every ‘Native Title Claim’. The most authoritative and comprehensive source for clarifying the confusion around clan/language boundaries is the Norman Tindale collection.