Sentiment and Geopolitics in the Formulation and Realization of the Balfour Declaration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEBEELE, Gerald Clarence, 1932- the PREDICAMENT of the BRITISH UNIONIST PARTY, 1906-1914

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 68-3000 HEBEELE, Gerald Clarence, 1932- THE PREDICAMENT OF THE BRITISH UNIONIST PARTY, 1906-1914. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by Gerald Clarence Heberle 1968 THE PREDICAMENT OF THE BRITISH UNIONIST PARTY, 1906-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gerald c / Heberle, B.A., M.A, ******* The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by B k f y f ’ P c M k ^ . f Adviser Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my deepest gratitude to Professor Philip P. Poirier of the Department of History, The Ohio State University, Dr. Poirier*s invaluable advice, his unfailing patience, and his timely encouragement were of immense assistance to me in the production of this dissertation, I must acknowledge the splendid service of the staff of the British Museum Manuscripts Room, The Librarian and staff of the University of Birmingham Library made the Chamberlain Papers available to me and were most friendly and helpful. His Lordship, Viscount Chilston, and Dr, Felix Hull, Kent County Archivist, very kindly permitted me to see the Chilston Papers, I received permission to see the Asquith Papers from Mr, Mark Bonham Carter, and the Papers were made available to me by the staff of the Bodleian Library, Oxford University, To all of these people I am indebted, I am especially grateful to Mr, Geoffrey D,M, Block and to Miss Anne Allason of the Conservative Research Department Library, Their cooperation made possible my work in the Conservative Party's publications, and their extreme kindness made it most enjoyable. -

The Sacred and the Profane

Kimberly Katz. Jordanian Jerusalem: Holy Places and National Spaces. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005. xvi + 150 pp. $59.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-8130-2844-6. Reviewed by Michael Fischbach Published on H-Levant (October, 2007) One of the topics that has generated consider‐ time) as well as to maintain these changing identi‐ able scholarly interest in the past decade, within ties in the face of powerful regional currents, the various disciplines dealing with modern Mid‐ forces, events, and neighbors that often (if not dle Eastern history, is the question of how nation‐ usually) have militated against these efforts. For al identity is created. Various factors, from socio- example, the fact that Jordan's Hashemite mon‐ economic to cultural and spatial, have been ana‐ archs have embraced and celebrated the lyzed by those seeking to discover how national Hashemite family's traditionalist and pro-Western communities--what Benedict Anderson's seminal Arab nationalist credentials frequently has collid‐ 1991 book calls "imagined communities"--are ed with the anti-Western, anti-colonial sentiments formed. Despite the fact that all the modern-day so often found among Arabs in the twentieth cen‐ states of the Fertile Crescent were creations of tury, including those living in Jordan itself. This Western imperialism, Jordan has been the subject was particularly true in the mid-twentieth centu‐ of particular focus in regard to this issue. What ry, when so many of the traditional values upon factors have gone into the creation of a Jordanian -

Arab-Israeli Relations

FACTSHEET Arab-Israeli Relations Sykes-Picot Partition Plan Settlements November 1917 June 1967 1993 - 2000 May 1916 November 1947 1967 - onwards Balfour 1967 War Oslo Accords which to supervise the Suez Canal; at the turn of The Balfour Declaration the 20th century, 80% of the Canal’s shipping be- Prepared by Anna Siodlak, Research Associate longed to the Empire. Britain also believed that they would gain a strategic foothold by establishing a The Balfour Declaration (2 November 1917) was strong Jewish community in Palestine. As occupier, a statement of support by the British Government, British forces could monitor security in Egypt and approved by the War Cabinet, for the establish- protect its colonial and economic interests. ment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. At the time, the region was part of Otto- Economics: Britain anticipated that by encouraging man Syria administered from Damascus. While the communities of European Jews (who were familiar Declaration stated that the civil and religious rights with capitalism and civil organisation) to immigrate of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine to Palestine, entrepreneurialism and development must not be deprived, it triggered a series of events would flourish, creating economic rewards for Brit- 2 that would result in the establishment of the State of ain. Israel forcing thousands of Palestinians to flee their Politics: Britain believed that the establishment of homes. a national home for the Jewish people would foster Who initiated the declaration? sentiments of prestige, respect and gratitude, in- crease its soft power, and reconfirm its place in the The Balfour Declaration was a letter from British post war international order.3 It was also hoped that Foreign Secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour on Russian-Jewish communities would become agents behalf of the British government to Lord Walter of British propaganda and persuade the tsarist gov- Rothschild, a prominent member of the Jewish ernment to support the Allies against Germany. -

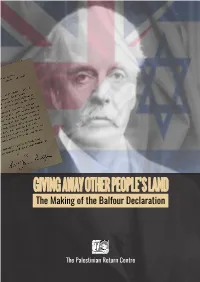

The Making of the Balfour Declaration

The Making of the Balfour Declaration The Palestinian Return Centre i The Palestinian Return Centre is an independent consultancy focusing on the historical, political and legal aspects of the Palestinian Refugees. The organization offers expert advice to various actors and agencies on the question of Palestinian Refugees within the context of the Nakba - the catastrophe following the forced displacement of Palestinians in 1948 - and serves as an information repository on other related aspects of the Palestine question and the Arab-Israeli conflict. It specializes in the research, analysis, and monitor of issues pertaining to the dispersed Palestinians and their internationally recognized legal right to return. Giving Away Other People’s Land: The Making of the Balfour Declaration Editors: Sameh Habeeb and Pietro Stefanini Research: Hannah Bowler Design and Layout: Omar Kachouch All rights reserved ISBN 978 1 901924 07 7 Copyright © Palestinian Return Centre 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publishers or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. مركز العودة الفلسطيني PALESTINIAN RETURN CENTRE 100H Crown House North Circular Road, London NW10 7PN United Kingdom t: 0044 (0) 2084530919 f: 0044 (0) 2084530994 e: [email protected],uk www.prc.org.uk ii Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 -

The Evolution of British Tactical and Operational Tank Doctrine and Training in the First World War

The evolution of British tactical and operational tank doctrine and training in the First World War PHILIP RICHARD VENTHAM TD BA (Hons.) MA. Thesis submitted for the award of the degree of Master of Philosophy by the University of Wolverhampton October 2016 ©Copyright P R Ventham 1 ABSTRACT Tanks were first used in action in September 1916. There had been no previous combat experience on which to base tactical and operational doctrine for the employment of this novel weapon of war. Training of crews and commanders was hampered by lack of vehicles and weapons. Time was short in which to train novice crews. Training facilities were limited. Despite mechanical limitations of the early machines and their vulnerability to adverse ground conditions, the tanks achieved moderate success in their initial actions. Advocates of the tanks, such as Fuller and Elles, worked hard to convince the sceptical of the value of the tank. Two years later, tanks had gained the support of most senior commanders. Doctrine, based on practical combat experience, had evolved both within the Tank Corps and at GHQ and higher command. Despite dramatic improvements in the design, functionality and reliability of the later marks of heavy and medium tanks, they still remained slow and vulnerable to ground conditions and enemy counter-measures. Competing demands for materiel meant there were never enough tanks to replace casualties and meet the demands of formation commanders. This thesis will argue that the somewhat patchy performance of the armoured vehicles in the final months of the war was less a product of poor doctrinal guidance and inadequate training than of an insufficiency of tanks and the difficulties of providing enough tanks in the right locations at the right time to meet the requirements of the manoeuvre battles of the ‘Hundred Days’. -

The Royal Air Force and Kuwait

THE ROYAL AIR FORCE AND KUWAIT Please return to the holder for other visitors. Introduction In January 1899 an agreement was reached between Kuwait and the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom agreed to pay an annual subsidy to Kuwait and take responsibility for its security. The Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913 con rmed Kuwait’s status as an autonomous region within the Ottoman Empire. The defeat and collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War One, however, led to an unstable situation. In 1920 border disputes led to warfare between Kuwaitis and the Ikhwan tribes from Nejd. At first it was the Ikhwan who were victorious but in October they raided Jahra and were defeated. Sheikh Salim al-Mubarak Al-Sabah of Kuwait claimed to be in control of all territory in a radius of 140 kilometres from the capital but Abdul Aziz ibn Abdul Rahman ibn Sa’ud claimed that the borders of Kuwait did not extend beyond the walls of its capital. The British Government, unwilling at first to intervene, confirmed that it recognised the borders laid down in the 1913 Convention. Eventually the British Government sent warships to protect the Kuwaiti capital and RAF aircraft dropped copies of a communique to the Ikhwan tribesmen. This helped create an uneasy truce between the two countries and established a no man’s land. The 1921 Cairo Conference, chaired by Winston Churchill, established Iraq as a kingdom under King Faisal within the British Mandate. The Royal Air Force was tasked with maintaining peace in the country; it took command with effect from 1 October 1922. -

Leo Amery at the India Office, 1940 – 1945

AN IMPERIALIST AT BAY: LEO AMERY AT THE INDIA OFFICE, 1940 – 1945 David Whittington A thesis submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education August 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii GLOSSARY iv INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTERS I LITERATURE REVIEW 10 II AMERY’S VIEW OF ATTEMPTS AT INDIAN CONSTITUTIONAL 45 REFORM III AMERY FROM THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT OF 1935 75 UNTIL THE AUGUST OFFER OF 1940 IV FROM SATYAGRAHA TO THE ATLANTIC CHARTER 113 V THE CRIPPS MISSION 155 VI ‘QUIT INDIA’, GANDHI’S FAST AND SOCIAL REFORM 205 IN INDIA VII A SUCCESSOR TO LINLITHGOW, THE STERLING BALANCES 253 AND THE FOOD SHORTAGES VIII FINAL ATTEMPTS AT CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM BEFORE THE 302 LABOUR ELECTION VICTORY CONCLUSION 349 APPENDICES 362 LIST OF SOURCES CONSULTED 370 ABSTRACT Pressure for Indian independence had been building up throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, initially through the efforts of the Indian National Congress, but also later, when matters were complicated by an increasingly vocal Muslim League. When, in May 1940, Leo Amery was appointed by Winston Churchill as Secretary of State for India, an already difficult assignment had been made more challenging by the demands of war. This thesis evaluates the extent to which Amery’s ultimate failure to move India towards self-government was due to factors beyond his control, or derived from his personal shortcomings and errors of judgment. Although there has to be some analysis of politics in wartime India, the study is primarily of Amery’s attempts at managing an increasingly insurgent dependency, entirely from his metropolitan base. -

The Armenians

THE ARMENIANS By C.F. DIXON-JOHNSON “Whosoever does wrong to a Christian or a Jew shall find me his accuser on the day of judgment.” (EL KORAN) Printed and Published by GEO TOULMIN & SONS, LTD. Northgate, Blackburn. 1916 Preface The following pages were first read as a paper before the “Société d’Etudes Ethnographiques.” They have since been amplified and are now being published at the request of a number of friends, who believe that the public should have an opportunity of judging whether or not “the Armenian Question” has another side than that which has been recently so assiduously promulgated throughout the Western World. Though the championship of Greek, Bulgarian and other similar “Christian, civilized methods of fighting,” as contrasted with “Moslem atrocities” in the Balkans and Asia Minor, has been so strenuously undertaken by Lord Bryce and others, the more recent developments in the Near East may perhaps already have opened the eyes of a great many thinking people to the realization that, in sacrificing the traditional friendship of the Turk to all this more or less sectarian clamor, British diplomacy has really done nothing better than to exchange the solid and advantageous reality for a most elusive and unreliable, if not positively dangerous, set of shadows. It seems illogical that the same party which recalled the officials (and among them our present War Minister) appointed by Lord Beaconsfield to assist the Turkish Government in reforming their administration and collecting the revenue in Asia Minor, and which on the advent of the Young Turks refused to lend British Administrators to whom ample and plenary powers were assured, should now, in its eagerness to vilify the Turk, lose sight of their own mistakes which have led in the main to the conditions of which it complains, and should so utterly condemn its own former policy. -

THE FRIENDS of EXETER CATHEDRAL ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Pages 27–31 ‘1917 and ALL THAT’ by Jonathan Walker

THE FRIENDS OF EXETER CATHEDRAL ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Pages 27–31 ‘1917 AND ALL THAT’ by Jonathan Walker ‘1917 AND ALL THAT’ It is not often that Hollywood has a link with Exeter Cathedral, but Sir Sam Mendes’ new blockbuster film ‘1917’ has created one. The film, which features cameo roles by Colin Firth and Dominic Cumberbatch, is set on the Western Front during The Great War and tells the story of two messengers who have to cross a surreal landscape, recently abandoned by the Germans, in order to deliver a message to a British battalion. That message aims to halt the unit’s intended suicidal attack, for the Germans have laid a trap. To say more, would be a ‘spoiler’ but the unit portrayed in the film is the 2nd Battalion The Devonshire Regiment – and Exeter Cathedral remains the spiritual home of the ‘Devons’, encompassing their regimental chapel of St Edmund. Before looking at the close association between the Devons and the Cathedral, what was the story of the county regiment’s contribution to The Great War? As with most regiments before the outbreak of the conflict, the Devons maintained two regular battalions of professional soldiers, a reserve battalion and three battalions of territorial (part-time) soldiers. There was a gulf between these units, with Lord Kitchener complaining, somewhat unjustly, that the Territorials were a collection of ‘middle-aged professional men who were allowed to put on uniform and play at soldiers’. Professional jealousy apart, it was clear that the British Army would have to be rapidly expanded, as the first weeks of the war decimated the ranks of the ‘old contemptibles’. -

From Sykes-Picot to Present; the Centenary Aim of the Zionism on Syria and Iraq

From Sykes-Picot to Present; The Centenary Aim of The Zionism on Syria and Iraq Ergenekon SAVRUN1 Özet Ower the past hundred years, much of the Middle East was arranged by Sir Mark Sykes and François Georges Picot. During the World War I Allied Powers dominanced Syria by the treaty of Sykes-Picot which was made between England and France. After the Great War Allied Powers (England-France) occupied Syria, Palestine, Iraq or all Al Jazeera and made them mandate. As the Arab World and Syria in particular is in turmoil, it has become fashionable of late to hold the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement responsible for the current storm surge. On the other hand, Theodor Herzl, the father of political Zionism, published a star-eyed novel entitled Altneuland (Old-New Land) in 1902. Soon after The Britain has became the biggest supporter of the Jews, but The Britain had to occupy the Ottoman Empire’s lands first with some allies, and so did it. The Allied Powers defeated Germany and Ottoman Empire. Nevertheless, the gamble paid off in the short term for Britain and Jews. In May 14, 1948 Israel was established. Since that day Israel has expanded its borders. Today, new opportunity is Syria just standing infront of Israel. We think that Israel will fill the headless body gap with Syrian and Iraqis Kurds with the support of Western World. In this article, we will emerge and try to explain this idea. Anahtar Kelimeler: Sykes-Picot Agrement, Syria-Iraq Issue, Zionism, Isreal and Kurds’ Relation. Sykes-Picot’dan Günümüze; Suriye ve Irak Üzerinde Siyonizm’in Yüz Yıllık Hedefleri Abstract Geçtiğimiz son yüzyılda, Orta Doğu’nun birçok bölümü Sir Mark Sykes ve François Georges Picot tarafından tanzim edildi. -

A2 Revision Guide British Empire 1914-1967 India

A2 Revision Guide British Empire 1914-1967 India 1906 All Muslim League founded- originally cooperated with Congress 1909 expressed belief in home rule, ‘Hind Swaraj’- favoured peaceful resistance based on satyagraha- insistence on the truth- rejecting violence to combat evil- appeal to moral conscience through strikes (hartals) and swadeshi (boycotts) Gandhi rejected caste system particularly against untouchables Wanted independent India- remain agricultural and rural and reject western industrialisation/ urbanisation Offered benefits of Western democracy/ liberalism whilst keeping Indian tradition. Non-violent methods were difficult for British- hit them economically and they couldn’t use violent oppression as it seemed disproportionate to methods used. Gandhi began career in S. Africa- campaigned against racism and segregation and challenged GB and Afrikaners from 1910 (dominant group after unification- descendants of Boers) 1913 Muhammad Ali Jinnah takes over Muslim League- originally favoured Hindu- Muslim co-op Approx. 1/3 of troops in Fr. In 1914 were Indian or GB soldiers who had served in India. Indian troops- major contributions to fight Middle East, and Africa (record less successful than Dominions). 1914 2/3 India’s imports came from GB but this began to fall- wartime disruption. India as capture domestic market more. After war desperate for £ to help control against nationalists GB put high taxes on Indian imports- 1917 11% to 1931 25%- protected Indian industry against competitors so there was growth. 1915 Gandhi returned to India, became President of Indian National Congress GB imports from India reduced from 7.3% to 6.1% 1925-29 but rose to 6.5% 1934-8. GB exports to India also reduced 11.9% 1909-13 to 8% 1934-8. -

"Weapon of Starvation": the Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2015 A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919 Alyssa Cundy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Cundy, Alyssa, "A "Weapon of Starvation": The Politics, Propaganda, and Morality of Britain's Hunger Blockade of Germany, 1914-1919" (2015). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1763. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1763 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A “WEAPON OF STARVATION”: THE POLITICS, PROPAGANDA, AND MORALITY OF BRITAIN’S HUNGER BLOCKADE OF GERMANY, 1914-1919 By Alyssa Nicole Cundy Bachelor of Arts (Honours), University of Western Ontario, 2007 Master of Arts, University of Western Ontario, 2008 DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in History Wilfrid Laurier University 2015 Alyssa N. Cundy © 2015 Abstract This dissertation examines the British naval blockade imposed on Imperial Germany between the outbreak of war in August 1914 and the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles in July 1919. The blockade has received modest attention in the historiography of the First World War, despite the assertion in the British official history that extreme privation and hunger resulted in more than 750,000 German civilian deaths.