Emily Wilding Davison (1872-1913)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosa Parks and Emily Davison

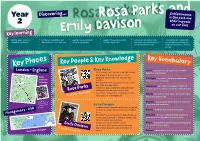

Year Achievements Discovering... in the past and 2 Rosa Parks andtheir impacts Emily Davison on our lives Key learning Identify what makes an Recognise similarities and Explain how Rosa Parks Explain how Emily Davison Recognise similarities and Understand and explain the individual significant. differences to 1955 and now. became significant. became significant. differences about RP and ED impact that Rosa Parks and and their achievements. Emily Davison had on modern society. Key Vocabulary Key Places Key People & Key Knowledge Rosa Parks Activist – a person who campaigns to bring about London - England • Civil rights activist in the mid to late 20th Century. political or social change. • She refused to give up her seat to a white Emily passenger on December 1st, 1955 and was Civil Rights – the rights of citizens to political and Davison’s arrested. social freedom and equality. birthplace • This launched the Montgomery bus boycott (5th Dec, 1995-20th Dec, 1996) Segregation – the enforced separation of different • At this time, black people were segregated and racial groups in a country, community or establishment. discriminated for the colour of their skin. Rosa Parks • Rosa Parks changed laws on segregation in the Equality – the state of being equal, especially in status. Feb 4, 1913 – Oct 24, 2005 USA, starting with transportation. Rights and opportunities. Carlisle Park, Prejudice – preconceived opinion that is not based on Northumberland reason or actual experience. – Statue of Emily Emily Davison Davison • A women’s equal rights activist who quit her job as a teacher to join the Women’s Social and Political Boycott – withdraw from something in protest. -

Process Paper and Bibliography

ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Books Kenney, Annie. Memories of a Militant. London: Edward Arnold & Co, 1924. Autobiography of Annie Kenney. Lytton, Constance, and Jane Warton. Prisons & Prisoners. London: William Heinemann, 1914. Personal experiences of Lady Constance Lytton. Pankhurst, Christabel. Unshackled. London: Hutchinson and Co (Publishers) Ltd, 1959. Autobiography of Christabel Pankhurst. Pankhurst, Emmeline. My Own Story. London: Hearst’s International Library Co, 1914. Autobiography of Emmeline Pankhurst. Newspaper Articles "Amazing Scenes in London." Western Daily Mercury (Plymouth), March 5, 1912. Window breaking in March 1912, leading to trials of Mrs. Pankhurst and Mr. & Mrs. Pethick- Lawrence. "The Argument of the Broken Pane." Votes for Women (London), February 23, 1912. The argument of the stone: speech delivered by Mrs Pankhurst on Feb 16, 1912 honoring released prisoners who had served two or three months for window-breaking demonstration in November 1911. "Attempt to Burn Theatre Royal." The Scotsman (Edinburgh), July 19, 1912. PM Asquith's visit hailed by Irish Nationalists, protested by Suffragettes; hatchet thrown into Mr. Asquith's carriage, attempt to burn Theatre Royal. "By the Vanload." Lancashire Daily Post (Preston), February 15, 1907. "Twenty shillings or fourteen days." The women's raid on Parliament on Feb 13, 1907: Christabel Pankhurst gets fourteen days and Sylvia Pankhurst gets 3 weeks in prison. "Coal That Cooks." The Suffragette (London), July 18, 1913. Thirst strikes. Attempts to escape from "Cat and Mouse" encounters. "Churchill Gives Explanation." Dundee Courier (Dundee), July 15, 1910. Winston Churchill's position on the Conciliation Bill. "The Ejection." Morning Post (London), October 24, 1906. 1 The day after the October 23rd Parliament session during which Premier Henry Campbell- Bannerman cold-shouldered WSPU, leading to protest led by Mrs Pankhurst that led to eleven arrests, including that of Mrs Pethick-Lawrence and gave impetus to the movement. -

The Battle of Equality Contents 1

The Battle Of Equality Contents 1. Contents 2. Women’s Rights 3. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. 4. Suffragettes 5. Suffragists 6. Who didn’t want women’s suffrage 7. Time Line of The Battle of Equality 8. Horse Derby 9. Pictures Woman’s Rights There were two groups that fought for woman's rights, the WSPU and the NUWSS. The NUWSS was set up by Millicent Fawcett. The WSPU was set up by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters. The WSPU was created because they didn’t want to wait for women’s rights by campaigning and holding petitions. They got bored so they created the WSPU. The WSPU went to the extreme lengths just to be heard. Whilst the NUWSS jus campaigned for women’s rights. 10 Famous women who made women’s suffrage happen. Emmeline Pankhurst (suffragette) - Leader of the suffragettes Christabel Pankhurst (suffragette)- Director of the most dangerous suffragette activities Constance Lytton (suffragette)- Daughter of viceroy Robert Bulwer-Lytton Emily Davison (suffragette)- Killed by kings horse Millicent Fawcett (suffragist)- Leader of the suffragist Edith Garrud (suffragette)- World professional Jiu-Jitsu master Silvia Pankhurst (suffragist)- Focused on campaigning and got expelled from the suffragettes by her sister Ethel Smyth (suffragette)- Conducted the suffragette anthem with a toothbrush Leonora Cohen (suffragette)- Smashed the display case for the Crown Jewels Constance Markievicz (suffragist)- Played a prominent role in ensuring Winston Churchill was defeated in elections Suffragettes The suffragettes were a group of women who wanted to vote. They did dangerous things like setting off bombs. The suffragettes were actually called The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). -

Identity of Suffragette Emily Wilding Davison Revealed in BFI Film

Scenes in the Record Demonstration of Suffragettes (1910), Emily Wilding Davison 2nd from right. Source: BFI National Archive Identity of Suffragette Emily Wilding Davison revealed in BFI film footage for the first time For Immediate release: 6 June 2018, London The BFI is thrilled to announce the discovery of previously unidentified moving image footage of iconic Suffragette Emily Wilding Davison revealed within a film of a Suffragettes procession in 1910, Scenes in the Record Demonstration of Suffragettes (1910) held by the BFI National Archive and available to view for free on BFI Player as part of the BFI’s Suffragettes on Film collection. This is a significant find as the only previously known footage featuring Emily Davison came from the 1913 Epsom Derby Day, in which she lost her life, and from her funeral procession. The discovery was made by writer and performer Deborah Clair who was watching the BFI’s Suffragettes on Film collection as research for her new play about Davison, A Necessary Woman. Whilst studying Scenes in the Record Demonstration of Suffragettes (1910) Deborah Clair thought she saw Emily Davison in the Suffragette procession, in her graduate gown and mortar board, “A familiar figure emerged. I instantly knew it was her right away and I even cried out, ‘Emily’ almost to get her attention! Then, even more strangely, the figure stops as the line temporarily halts and she looks directly at the camera. I could see her up close, in motion, for the first time. She was alive and she looked – defiant!” Clair compared the moving image to a photo she knew of Davison held by the National Portrait Gallery. -

The Case of the UK Suffragettes (1906–1914)

G Model SON-733; No. of Pages 11 ARTICLE IN PRESS Social Networks xxx (2012) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Social Networks journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/socnet Covert social movement networks and the secrecy-efficiency trade off: The case ଝ of the UK suffragettes (1906–1914) ∗ Nick Crossley , Gemma Edwards, Ellen Harries, Rachel Stevenson Mitchell Centre for Social Network Analysis, School of Social Sciences, University of Manchester, UK a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Keywords: This paper formulates and empirically tests a number of hypotheses regarding the impact of covertness Covert networks upon network structure. Specifically, hypotheses are deduced from theoretical arguments regarding a Secrecy-efficiency trade off ‘secrecy-efficiency trade off’ which is said to shape covert networks. The paper draws upon data con- Social movements cerning the UK suffragettes. It is taken from a publicly archived UK Home Office document listing 1992 Suffragettes court appearances (for suffrage related activities), involving 1214 individuals and 394 court sessions, between 1906 and 1914. Network structure at earlier phases of suffragette activism, when the move- ment was less covert, is compared with that during the final phase, when it was more covert and meets the definitional criteria of what we call a ‘covert social movement network’ (CSMN). Support for the vari- ous hypotheses tested is variable but the key claims derived from the idea of the secrecy-efficiency trade off are supported. Specifically, the suffragettes’ network becomes less dense and less degree centralised as it becomes more covert. -

Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliography Primary Sources: Anonymous, “Women's Suffrage: The Right to The Vote”, n.d. This image shows an example of a poster that supported the Suffragettes’ cause. There have been numerous posters with a similar design. On this poster is Joan of Arc, an important figure to the Suffragettes, holding a banner that says “The Right to The Vote”. “ALL THE SUFFRAGIST LEADERS ARRESTED: “WE WILL ALL STARVE TO DEATH IN PRISON UNLESS WE ARE FORCIBLY FED”” The Daily Sketch, http://www.spirited.org.uk/object/daily-sketch-shows-the-method-used-for-force-feeding-suf fragettes This is an image of a newspaper during the force-feeding of Suffragettes. This image describes the strength and sacrifice that Suffragettes were willing to make. Barratt's Photo Press Ltd. “Suffragette Struggling with a Policeman on Black Friday.” The Museum of London, London , 14 Nov. 2018, www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/black-friday. This photograph was taken during the police brutality during protests against the failure of the Conciliation Bill. It was compiled by Barratt’s Photo Press Ltd. in 1910. Bathurst, G. “The National Archives .” Received by First Commissioner of His Majesty’s Works, The National Archives , 6 Apr. 1910. WORK 11/117, www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/suffragettes-on-file/hiding-in-parliament/. This was a letter written by G. Bathurst, Chief Clark of the Commissioner of Police of the Metropolis, to inform the First Commissioner of His Majesty’s Works about the actions of Emily Wilding Davison. Emily Wilding Davison was an important Suffragette who eventually became the Suffragette martyr in 1913 when she ran in front of the King’s horse during a derby. -

The, Suffragette Movement in Great Britain

/al9 THE, SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT IN GREAT BRITAIN: A STUDY OF THE FACTORS INFLUENCING THE STRATEGY CHOICES OF THE WOMEN'S SOCIAL AND POLITICAL UNION, 1903-1918 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Derril Keith Curry Lance, B. S. Denton, Texas. December, 1977 Lance, Derril Keith Curry, The Suffragette Movement in Great Britain: A Study of the Factors Influencing the Strategy Choices of the Women's Social and Political Union, 1903-1918, Master of Science (Sociology), Decem- ber, 1977, 217 pp., 4 tables, bibliography, 99 titles. This thesis challenges the conventional wisdom that the W.S.P.U.'s strategy choices were unimportant in re- gard to winning women's suffrage. It confirms the hypo- thesis that the long-range strategy of the W.S.P.U. was to escalate coercion until the Government exhausted its powers of opposition and conceded, but to interrupt this strategy whenever favorable bargaining opportunities with the Government and third parties developed. In addition to filling an apparent research gap by systematically analyzing these choices, this thesis synthesizes and tests several piecemeal theories of social movements within the general framework of the natural history approach. The analysis utilizes data drawn from movement leaders' auto- biographies, documentary accounts of the militant movement, and the standard histories of the entire British women's suffrage movement. Additionally, extensive use is made of contemporary periodicals and miscellaneous works on related movements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . Chapter I. -

The Death of Suffragette Emily Wilding Davison: the Manchester Guardian's Response | from the Guardian | Guardian.Co.Uk

The death of suffragette Emily Wilding Davison: The Manchester Guardian's response How the paper reported on the death of the militant suffragist - and the reaction of its readers Emily Davison a few days before her fatal attempt to stop the King's horse 'Amner' on Derby Day to draw attention to the Women's Suffragette movement. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images Emily Wilding Davison, the militant suffragist who stepped out in front of the King's horse on 4 June 1913, died from her injuries four days later. The Manchester Guardian reported the death and printed an editorial that acknowledged her courage and resolution but noted that because of her actions "In effect, though not in intention, she has committed suicide to keep women voteless and "militancy" prominent. The Manchester Guardian, 11 June 1913. Click on image to read full article. In response, the paper received a vast number of letters including one from the suffragist, and regular Guardian contributor, Evelyn Sharp (see below). The Manchester Guardian, 11 June 1913 To this, CP Scott, the paper's editor, added an editorial footnote (something he often did), reiterating the point that "militancy" was an obstacle to women's suffrage. More letters appeared on the 12 June. Emily Wilding Davison herself had written to the paper in December 1911 (see below), declaring that "No deserving cause could succeed by violence. The success of violence is the test of righteousness of the cause." Scott's footnote to this letter read: The really ludicrous position is the Mr Lloyd George is fighting to enfranchise seven million women and the militants are smashing unoffending people's windows and breaking up benevolent societies' meetings in a desperate effort to prevent him. -

Emily Davison May Be a Familiar Name to You As the Suffragette Who Threw

Emily Davison may be a familiar name to you as the suffragette who documenting the Suffrage campaign threw herself under a horse and who is often dismissed as typical of have found little information about her the lunatic fringe' of the Women's Social and Political Union. and so have either excluded her entirely from their accounts or have cast her When Rebecca Ferguson was a student at the Royal Holloway into strange, very inappropriate roles. College, which Emily herself attended, she was prompted to look She has been described as a statuesque, into the rest of her story. Emily's commitment to civil disobedience red-headed beauty, going to her death with an Amazon-like dignity; as a and direct action symbolizes the militancy in the suffrage campaign mystic and a visionary who thought she that hides behind its more respectable history. was Joan of Arc; or as an hysterical, even insane woman who did not know what she was doing. The accounts of he day after the Derby in to give all the worid the knowledge that those who knew her prove each of those 1913, Emily reached the a Suffragette, in the full tide of life and pictures wrong. headlines of all the papers. energy, had died for her faith, Emily Emily was born and spent her child Some even had a photograph Davison left for her comrades in the hood in Northumberland, where her of her being thrown to the ground. The fight an ineffaceable impression of a life family remained while she moved away Suffragette magazine devoted a whole consecrated to one great end.' to attend school in Kensington. -

Facebook.Com/Scottishsocialistvoice @Ssv Voice INDEPENDENCE

One year on: Colin Fox Emily: Denise on the mass grassroots Morton on Emily pro-indy campaign Davison’s legacy • see page 5 • see page 9 £1 • issue 419 • 7th - 20th June 2013 facebook.com/scottishsocialistvoice Labour, Tories: BITTER AS bankers’ pal Alastair Darling wooed the dwindling band of Scottish Tories in Stirling, Labour unionist splits - led by Gordon Brown - widened. TOGETAH growing reEvulsion R at sharing a platform with the Tories and Lib Dems behind the savage austerity cuts saw the first No camp split, with ‘United With Labour’ going their own way. Former Labour MP and MSP John McAllion lifts the lid on the DAVID CAMERON: master of cuts ALISTAIR DARLING: ‘UK OK’ murky stew - see page 3... facebook.com/ScottishSocialistVoice @ssv_voice INDEPENDENCE bLy Kaen bFergouson ur and Tories: bitter toachigevements itn bhenefiets, her alth and social provision - all accom - As the latest round of benefit cuts panied by crocodile tears and hand slash the income of the disabled wringing about “hard times”. and Bedroom Tax horror tales grow The truth is that Labour is in the anybody looking for relief from midst of a wholesale break with its Labour had their hopes dashed by historic past achievements under shadow chancellor Ed Balls who the cloak of making “communi - warned of “iron rule” and cuts in ties” responsible for services and winter payments to wealthier pen - sub letting key services to the vol - sioners under Labour. untary sector in what will amount The latest stage in the auction to to back door privatisation. prove who can be toughest on the poor, ConDems or Labour, came Fault line as it was revealed that former Anyone with illusions about Labour Chancellor Alistair Dar - being saved from the wicked To - ling is speaking at the conference ries by valiant Labour needs ur - of that isolated fringe group, the BALLS! shadow chancellor warned of ‘iron rule’ and more cuts gently to read the not so small Scottish Tories, as Better Together print and understand that Red Ed, chief. -

The Suffragette As Militant Artist

The Suffragette as Militant Artist The Suffragette as Militant Artist Suffragette artists & suffragette attacks on art A gift from The Emily Davison Lodge, 2010 Dare to be Free! Information collated and artistic impressions created in response to archival material by Olivia Plender & Hester Reeve With thanks to – Gail Cameron & Inderbir Bhullar (The Women’s Library) Anna Colin (curator) Jamie Crewe (lay out) Matthew Booth (photographer) Created and published by The Emily Davison Lodge, 2010 Suffragette Attacks on Art Suffragettes Date Location Artwork Tool! Solo Suffragette 1894 The Royal Stanhope Alexander Forbes’ Umbrella (possibly Ethel Cox, Academy “The Quarry team” alias of Gwendoline Cook, who is on a M.O.D file held by the National Gallery archives as a suspected slasher and not mentioned in any other reported incidences) Sylvia Pankhurst 14/1/13 St Stephen’s “Speaker Finch being held in the chair” Lump of concrete (artist and one of the Hall, Parliament WSPU leaders) Buildings A productive artist throughout the campaign, Sylvia Pankhurst nonetheless doubted, “…whether it was worthwhile to fight one’s individual struggle…to make one’s way as an artist, to bring out of oneself the best possible, and to induce the world to accept one’s creations, and give one in return ones’ daily bread, when all the time the real struggles to better the world for humanity demand another service.” Evelyn Manesta, 3/4/13 Manchester Art Smash glass of 13 paintings, damage: Hammer Lillian Forrester & Gallery Frederick Leighton’s “ Captive & one other (Sarah Andromache,” Jane/Jennie- Geroge Frederic Watts’ “Paolo & Baines?) Francesca” and “The Prayer,” (Forrester had taken Arthur Hacker’s “Syrinx” part in the 1911 window smashing) Mary Richardson 10/3/14 National Velázquez “Rokeby Venus” (The Toilet Butcher’s Chopper – 5 slashes aka “Slasher Mary” Gallery of Venus) across the nude’s body. -

A Virtual Museum by Nefeli Tsamili Welcomewelcome Toto Mymy Extensionextension Ofof Suffragesuffrage Museum!Museum!

TheThe extensionextension ofof suffragesuffrage A virtual museum by Nefeli Tsamili WelcomeWelcome toto mymy ExtensionExtension OfOf SuffrageSuffrage Museum!Museum! Ready to travel back to a monumental moment in British history? Then let's start travelling back in time and learn about the time when women fought for the right to vote! WhatWhat was was a a suffragette? suffragette? A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisations in the early 20th century The term refers in who, under the banner particular to members of "Votes for Women", the British Women's fought for the right to Social and Political vote in public elections, Union (WSPU), a known as women's women-only movement suffrage. founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, which engaged in direct action and civil disobedience. How the suffragettes used fashion to further their cause Dress is a powerful form of communication. No-one knew this better than the media-savvy leadership of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The suffragettes wanted to avoid accusations of eccentricity or spinsterish masculinity. They recognised their best chance of winning the vote was to align themselves, at least outwardly, with Edwardian ideals of femininity, even if they were engaging in defiantly unladylike activities under the radar. The WSPU was also canny enough to learn from the mistakes of previous generations. The fight for female emancipation had been going on for decades. In the 19th century, the drive for equality became closely associated with the dress reform movement, which sought to free women from the constriction of a Victorian silhouette, with its attendant corsetry and crinolines.