CM 2-08.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science @ the Symphony Ontario Science Centre, Concert Partner

Science @ the Symphony Ontario Science Centre, concert partner The Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s Student Concerts are generously supported by Mrs. Gert Wharton and an anonymous donor. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra gratefully acknowledges Sarah Greenfield for preparing the lesson plans for the Junior/Intermediate Student Concert Study Guide. Junior/Intermediate Level Student Concert Study Guide Study Concert Student Level Junior/Intermediate Table of Contents Table of Contents 1) Concert Overview & Repertoire Page 3 2) Composer Biographies and Programme Notes Page 4 - 11 3) Unit Overview & Lesson Plans Page 12 - 23 4) Lesson Plan Answer Key Page 24 - 30 5) Artist Biographies Page 32 - 34 6) Musical Terms Glossary Page 35 - 36 7) Instruments in the Orchestra Page 37 - 45 8) Orchestra Seating Chart Page 46 9) Musicians of the TSO Page 47 10) Concert Preparation Page 48 11) Evaluation Forms (teacher and student) Page 49 - 50 The TSO has created a free podcast to help you prepare your students for the Science @ the Symphony Student Concerts. This podcast includes excerpts from pieces featured on the programme, as well as information about the instruments featured in each selection. It is intended for use either in the classroom, or to be assigned as homework. To download the TSO Junior/Intermediate Student Concert podcast please visit www.tso.ca/studentconcerts, and follow the links on the top bar to Junior/Intermediate. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra wishes to thank its generous sponsors: SEASON PRESENTING SPONSOR OFFICIAL AIRLINE SEASON -

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

Concierto Barroco: Estudios Sobre Música, Dramaturgia E Historia Cultural

CONCIERTO BARROCO Estudios sobre música, dramaturgia e historia cultural CONCIERTO BARROCO Estudios sobre música, dramaturgia e historia cultural Juan José Carreras Miguel Ángel Marín (editores) UNIVERSIDAD DE LA RIOJA 2004 Concierto barroco: estudios sobre música, dramaturgia e historia cultural de Juan José Carreras y Miguel Ángel Marín (publicado por la Universidad de La Rioja) se encuentra bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2012 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-84-695-4053-4 Afinaban cuerdas y trompas los músicos de la orquesta, cuando el indiano y su servidor se instalaron en la penumbra de un palco. Y, de pronto, cesaron los martillazos y afinaciones, se hizo un gran silencio y, en el puesto de director, vestido de negro, violín en mano, apareció el Preste Antonio, más flaco y narigudo que nunca […] Metido en lo suyo, sin volverse para mirar a las pocas personas que, aquí, allá, se habían colocado en el teatro, abrió lentamente un manuscrito, alzó el arco —como aquella noche— y, en doble papel de director y de ejecutante impar, dio comienzo a la sinfonía, más agitada y ritmada —acaso— que otras sinfonías suyas de sosegado tempo, y se abrió el telón sobre un estruendo de color… Alejo Carpentier, Concierto barroco ÍNDICE PRÓLOGO . 11 INTRODUCCIÓN . 13 PARTE I 1. Juan José Carreras Ópera y dramaturgia . 23 Nota bibliográfica 2. Martin Adams La “dramatic opera” inglesa: ¿un imposible género teatral? . -

Motezuma.Pdf

2. Traum von der Ferne „Sieh an mein Gesicht voll Tugend und Wert, doch dein perverses Herz zeigt mir sogleich, wie grausam und wild du bist.“ (Fernando) Theater und Philharmonisches Orchester der Stadt Heidelberg Antonio Vivaldi Motezuma Uraufführung im Teatro Sant‘Angelo, Venedig, am 14. November 1733 Antonio Vivaldi Motezuma * 08.12.06 Oper in drei Akten Koproduktion mit dem Libretto von Alvise Giusti Luzerner Theater Uraufführung der Wir danken der Heidelberger Fassung Schlossverwaltung Schwetzingen Transkription des Fragments: & dem Autohaus Jonckers. Steffen Voss Das Cembalo wird durch Merzdorf Neukomposition: Thomas Leininger Cembalobau zur Verfügung gestellt. In italienischer Sprache mit deutschen Übertiteln 04 Besetzung Motezuma, Kaiser der Azteken Asprano, mexikanischer General Sebastian Geyer Silke Schwarz Mitrena, seine Frau Alebrije Rosa Dominguez Yusuf Erdugan Teutile, seine Tochter Azteken Michaela Maria Mayer Xaver Bachmann Yusuf Erdugan Fernando (Hernan Cortés) Emil Kraft Maraile Lichdi Philipp Schüfer Birtan Özkan Ramiro, sein Bruder & Teutiles Liebhaber Jana Kurucová 05 Inszenierungsteam Engel Musikalische Leitung Emil Kraft Michael Form Spanier Regie Kahwe Knapp / Michael Schlösser Martín Acosta Businessman, Astronaut Bühne und Kostüme Eberhard Bühler Humberto Spíndola Museumswächter, Astronaut, Priester Lichtdesign Eren Gövercin Andreas Rinkes Götter Chor Xaver Bachmann / Philipp Schüfer Tarmo Vaask 06 Dramaturgie, Übertitel Ausstattungsassistenz Bernd Feuchtner Bettina Ernst Musikalische Assistenz & Rezitative Souffl -

Antonio Lucio VIVALDI

AN IMPORTANT NOTE FROM Johnstone-Music ABOUT THE MAIN ARTICLE STARTING ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE: We are very pleased for you to have a copy of this article, which you may read, print or save on your computer. You are free to make any number of additional photocopies, for johnstone-music seeks no direct financial gain whatsoever from these articles; however, the name of THE AUTHOR must be clearly attributed if any document is re-produced. If you feel like sending any (hopefully favourable) comment about this, or indeed about the Johnstone-Music web in general, simply vis it the ‘Contact’ section of the site and leave a message with the details - we will be delighted to hear from you ! Una reseña breve sobre VIVALDI publicado por Músicos y Partituras Antonio Lucio VIVALDI Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Venecia, 4 de marzo de 1678 - Viena, 28 de julio de 1741). Compositor del alto barroco, apodado il prete rosso ("el cura rojo" por ser sacerdote y pelirrojo). Compuso unas 770 obras, entre las cuales se cuentan 477 concerti y 46 óperas; especialmente conocido a nivel popular por ser el autor de Las cuatro estaciones. johnstone-music Biografia Vivaldi un gran compositor y violinista, su padre fue el violinista Giovanni Batista Vivaldi apodado Rossi (el Pelirrojo), fue miembro fundador del Sovvegno de’musicisti di Santa Cecilia, organización profesional de músicos venecianos, así mismo fue violinista en la orquesta de la basílica de San Marcos y en la del teatro de S. Giovanni Grisostomo., fue el primer maestro de vivaldi, otro de los cuales fue, probablemente, Giovanni Legrenzi. -

Howard Mayer Brown Microfilm Collection Guide

HOWARD MAYER BROWN MICROFILM COLLECTION GUIDE Page individual reels from general collections using the call number: Howard Mayer Brown microfilm # ___ Scope and Content Howard Mayer Brown (1930 1993), leading medieval and renaissance musicologist, most recently ofthe University ofChicago, directed considerable resources to the microfilming ofearly music sources. This collection ofmanuscripts and printed works in 1700 microfilms covers the thirteenth through nineteenth centuries, with the bulk treating the Medieval, Renaissance, and early Baroque period (before 1700). It includes medieval chants, renaissance lute tablature, Venetian madrigals, medieval French chansons, French Renaissance songs, sixteenth to seventeenth century Italian madrigals, eighteenth century opera libretti, copies ofopera manuscripts, fifteenth century missals, books ofhours, graduals, and selected theatrical works. I Organization The collection is organized according to the microfilm listing Brown compiled, and is not formally cataloged. Entries vary in detail; some include RISM numbers which can be used to find a complete description ofthe work, other works are identified only by the library and shelf mark, and still others will require going to the microfilm reel for proper identification. There are a few microfilm reel numbers which are not included in this listing. Brown's microfilm collection guide can be divided roughly into the following categories CONTENT MICROFILM # GUIDE Works by RISM number Reels 1- 281 pp. 1 - 38 Copies ofmanuscripts arranged Reels 282-455 pp. 39 - 49 alphabetically by institution I Copies of manuscript collections and Reels 456 - 1103 pp. 49 - 84 . miscellaneous compositions I Operas alphabetical by composer Reels 11 03 - 1126 pp. 85 - 154 I IAnonymous Operas i Reels 1126a - 1126b pp.155-158 I I ILibretti by institution Reels 1127 - 1259 pp. -

The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection

• The Howard Mayer Brown Libretto Collection N.B.: The Newberry Library does not own all the libretti listed here. The Library received the collection as it existed at the time of Howard Brown's death in 1993, with some gaps due to the late professor's generosity In loaning books from his personal library to other scholars. Preceding the master inventory of libretti are three lists: List # 1: Libretti that are missing, sorted by catalog number assigned them in the inventory; List #2: Same list of missing libretti as List # 1, but sorted by Brown Libretto Collection (BLC) number; and • List #3: List of libretti in the inventory that have been recataloged by the Newberry Library, and their new catalog numbers. -Alison Hinderliter, Manuscripts and Archives Librarian Feb. 2007 • List #1: • Howard Mayer Brown Libretti NOT found at the Newberry Library Sorted by catalog number 100 BLC 892 L'Angelo di Fuoco [modern program book, 1963-64] 177 BLC 877c Balleto delli Sette Pianeti Celesti rfacsimile 1 226 BLC 869 Camila [facsimile] 248 BLC 900 Carmen [modern program book and libretto 1 25~~ Caterina Cornaro [modern program book] 343 a Creso. Drama per musica [facsimile1 I 447 BLC 888 L 'Erismena [modern program book1 467 BLC 891 Euridice [modern program book, 19651 469 BLC 859 I' Euridice [modern libretto and program book, 1980] 507 BLC 877b ITa Feste di Giunone [facsimile] 516 BLC 870 Les Fetes d'Hebe [modern program book] 576 BLC 864 La Gioconda [Chicago Opera program, 1915] 618 BLC 875 Ifigenia in Tauride [facsimile 1 650 BLC 879 Intermezzi Comici-Musicali -

Antonio Vivaldi from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Antonio Vivaldi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Antonio Lucio Vivaldi (Italian: [anˈtɔːnjo ˈluːtʃo viˈvaldi]; 4 March 1678 – 28 July 1741) was an Italian Baroque composer, virtuoso violinist, teacher and cleric. Born in Venice, he is recognized as one of the greatest Baroque composers, and his influence during his lifetime was widespread across Europe. He is known mainly for composing many instrumental concertos, for the violin and a variety of other instruments, as well as sacred choral works and more than forty operas. His best-known work is a series of violin concertos known as The Four Seasons. Many of his compositions were written for the female music ensemble of the Ospedale della Pietà, a home for abandoned children where Vivaldi (who had been ordained as a Catholic priest) was employed from 1703 to 1715 and from 1723 to 1740. Vivaldi also had some success with expensive stagings of his operas in Venice, Mantua and Vienna. After meeting the Emperor Charles VI, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, hoping for preferment. However, the Emperor died soon after Vivaldi's arrival, and Vivaldi himself died less than a year later in poverty. Life Childhood Antonio Lucio Vivaldi was born in 1678 in Venice, then the capital of the Republic of Venice. He was baptized immediately after his birth at his home by the midwife, which led to a belief that his life was somehow in danger. Though not known for certain, the child's immediate baptism was most likely due either to his poor health or to an earthquake that shook the city that day. -

Descriptive Leaflet

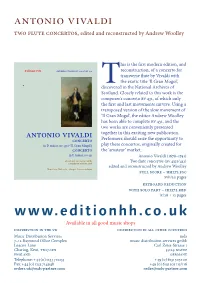

antonio vivaldi two flute concertos, edited and reconstructed by Andrew Woolley his is the first modern edition, and Edition HH antonio vivaldi: rv 431a / rv 431 reconstruction, of a concerto for transverse flute by Vivaldi with the exotic title ‘Il Gran Mogol’, Tdiscovered in the National Archives of Scotland. Closely related to this work is the composer’s concerto rv 431, of which only the first and last movements survive. Using a transposed version of the slow movement of ‘Il Gran Mogol’, the editor Andrew Woolley has been able to complete rv 431, and the two works are conveniently presented antonio vivaldi together in this exciting new publication. concerto Performers should seize the opportunity to in D minor, rv 431a (‘Il Gran Mogol’) play these concertos, originally created for concerto the ‘amateur’ market. in E minor, rv 431 Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) edited and reconstructed by Two flute concertos (rv 431a/431) andrew woolley edited and reconstructed by Andrew Woolley Transverse flute solo · strings · basso continuo full score – hh272.fsc xvii/30 pages keyboard reduction with solo part – hh272.kbd ix/28 + 12 pages www.editionhh.co.uk Available in all good music shops distribution in the uk distribution in all other countries Music Distribution Services mds 7– 12 Raywood Office Complex music distribution services gmbh Leacon Lane Carl Zeiss-Strasse 1 Charing, Kent, tn27 0en 55129 mainz england germany Telephone: +44 (0) 1233 712233 +49 (0) 6131 505 100 Fax: +44 (0) 1233 714948 +49 (0) 6131 505 115/116 [email protected] [email protected] Edition HH should be applauded for their willingness to seek out rare but wholly worthwhile repertoire, Edition HH and their knack of bringing it to our attention Edition HH Ltd through extremely high quality and usable editions. -

Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

Ospedale della Pietà in Venice Opernhaus Prag Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Complete Opera – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Index - Complete Operas by Antonio Vivaldi Page Preface 3 Cantatas 1 RV687 Wedding Cantata 'Gloria e Imeneo' (Wedding cantata) 4 2 RV690 Serenata a 3 'Mio cor, povero cor' (My poor heart) 5 3 RV693 Serenata a 3 'La senna festegiante' 6 Operas 1 RV697 Argippo 7 2 RV699 Armida al campo d'Egitto 8 3 RV700 Arsilda, Regina di Ponto 9 4 RV702 Atenaide 10 5 RV703 Bajazet - Il Tamerlano 11 6 RV705 Catone in Utica 12 7 RV709 Dorilla in Tempe 13 8 RV710 Ercole sul Termodonte 14 9 RV711 Farnace 15 10 RV714 La fida ninfa 16 11 RV717 Il Giustino 17 12 RV718 Griselda 18 13 RV719 L'incoronazione di Dario 19 14 RV723 Motezuma 20 15 RV725 L'Olimpiade 21 16 RV726 L'oracolo in Messenia 22 17 RV727 Orlando finto pazzo 23 18 RV728 Orlando furioso 24 19 RV729 Ottone in Villa 25 20 RV731 Rosmira Fedele 26 21 RV734 La Silvia (incomplete) 27 22 RV736 Il Teuzzone 27 23 RV738 Tito Manlio 29 24 RV739 La verita in cimento 30 25 RV740 Il Tigrane (Fragment) 31 2 – Antonio Vivaldi – Complete Opera – Preface In 17th century Italy is quite affected by the opera fever. The genus just newly created is celebrated everywhere. Not quite. For in Romee were allowed operas for decades heard exclusively in a closed society. The Papal State, who wanted to seem virtuous achieved at least outwardly like all these stories about love, lust, passions and all the ancient heroes and gods was morally rather questionable. -

CHRISTMAS Christmas with Naxos

CATALOGUE 2018 CHRISTMAS Christmas with Naxos Christmas is one of the most richly celebrated seasons around the world. While its focus rests on just a few days of the year, the wealth of music that has been written to mark its spirit and story is astonishingly plentiful and varied. Musicians continue to be inspired by the message of Christmas: in the following pages you will find examples of contemporary choral works by British composers John Tavener, James MacMillan and Sasha Johnson Manning alongside the established masterpieces of composers such as J. S. Bach, Handel and Berlioz. The Christmas story has also been recorded in opera, ballet and instrumental music, in a range of expression that runs from piety to jollity. Easy-listening compilations are well represented in the listings, including regional collections and the gamut of carols that are annual favourites, heard either in the splendour of Europe's historic cathedrals or in the local community. We hope our catalogue will serve you with music that is both comfortingly familiar and refreshingly novel. May you spend a very happy Christmas with Naxos. Contents Listing by Composer ...............................................................................................................................4 Collections .............................................................................................................................................15 Audiovisual ............................................................................................................................................27 -

Meisterklasse Gesang Mit Adrian Eröd Mit Studierenden Des Studiengangs Gesang Und Oper (Leitung: Yuly Khomenko)

Meisterklasse Gesang mit Adrian Eröd mit Studierenden des Studiengangs Gesang und Oper (Leitung: Yuly Khomenko) Dienstag, 1. März 2016 20.00 Uhr Eine Kooperation der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien und der Musik und Kunst Privatuniversität der Stadt Wien. Wiener Musikverein Gläserner Saal/Magna Auditorium Musikvereinsplatz 1 1010 Wien EINFÜHRUNG & PROGRAMM Seit Jahren begeistert der österreichische Bariton Adrian Eröd an seinem Stammhaus, der Wiener Staatsoper, wie auch international Publikum und Presse mit seiner Vielfältigkeit als Sänger. Auch auf dem Konzertpodium ist er äußerst erfolgreich, mit dem Wiener Musik- verein verbindet ihn eine sehr enge und erfolgreiche Zusammenarbeit. Adrian Eröds Meisterklasse für Studierende des Studiengangs Gesang und Oper (Leitung: Yuly Khomenko) der Musik und Kunst Privatuniversität der Stadt Wien gewährt spannende Einblicke in die Ausbildung von jungen Sängerinnen und Sängern. Vielleicht gilt es dabei sogar, den einen oder anderen Star von morgen zu entdecken! PROGRAMM Franz Schubert (1797–1828) Ganymed D 544 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe) Andrea Purtic, Mezzosopran Robert Schumann (1810–1856) Stille Tränen op. 35 Nr. 10 (Justinus Kerner) Kristján Jóhannesson, Bariton Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) aus La clemenza di Tito KV 621 Duett Nr. 7 Servilia – Annio „Ah perdona il primo affetto“ Servilia: Nataliya Stepanyak, Sopran Annio: Ghazal Kazemiesfeh, Mezzosopran Pause 2 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart aus La clemenza di Tito KV 621 Terzett Nr. 18 Tito – Sesto – Publio „Quello di Tito è il volto!“ Tito: Jinhun Lee, Tenor Sesto: Eyrun Unnarsdottir, Mezzosopran Publio: Tair Tazhigulov, Bass Robert Schumann Reich mir die Hand op. 104 Nr. 5 (Elisabeth Kulmann) Anna-Sophie Kostal, Sopran Franz Schubert aus Schwanengesang D 957 Nr.