10 Duncan.Indd 333 4/21/08 10:13:52 AM 334 Duncan Mccargo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011

Thai Netizen Network Annual Report: Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011 An annual report of Thai Netizen Network includes information, analysis, and statement of Thai Netizen Network on rights, freedom, participation in policy, and Thai internet culture in 2011. Researcher : Thaweeporn Kummetha Assistant researcher : Tewarit Maneechai and Nopphawhan Techasanee Consultant : Arthit Suriyawongkul Proofreader : Jiranan Hanthamrongwit Accounting : Pichate Yingkiattikun, Suppanat Toongkaburana Original Thai book : February 2012 first published English translation : August 2013 first published Publisher : Thai Netizen Network 672/50-52 Charoen Krung 28, Bangrak, Bangkok 10500 Thailand Thainetizen.org Sponsor : Heinrich Böll Foundation 75 Soi Sukhumvit 53 (Paidee-Madee) North Klongton, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand The editor would like to thank you the following individuals for information, advice, and help throughout the process: Wason Liwlompaisan, Arthit Suriyawongkul, Jiranan Hanthamrongwit, Yingcheep Atchanont, Pichate Yingkiattikun, Mutita Chuachang, Pravit Rojanaphruk, Isriya Paireepairit, and Jon Russell Comments and analysis in this report are those of the authors and may not reflect opinion of the Thai Netizen Network which will be stated clearly Table of Contents Glossary and Abbreviations 4 1. Freedom of Expression on the Internet 7 1.1 Cases involving the Computer Crime Act 7 1.2 Internet Censorship in Thailand 46 2. Internet Culture 59 2.1 People’s Use of Social Networks 59 in Political Movements 2.2 Politicians’ Use of Social -

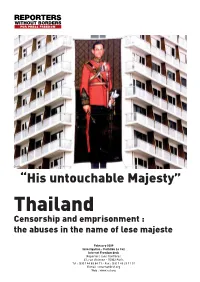

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

27 Bangkok Indexit.Indd 339 12/15/11 11:00:18 AM 340 Index

Index 339 INDEX A amnesty, 279–83, 285, 301, 303 Abhisit Vejjajiva, 5, 7–8, 20, 25, 27, Amnuay Virawan, 17 30–31, 38–40, 43–45, 47, 72, Amsterdam, Robert, 280–81 77–80, 100, 120, 123–5, 132, 135, Anan Panyarachun, 44, 104, 169, 144, 165–66, 168, 173, 178, 182, 305–306 186, 194, 200–201, 245, 253, Ananda Mahidol, King, 73, 180 257–62, 274–76, 282–83, 285, 290, ancien régime, 287, 295 294, 298, 313, 319, 321, 323 Angkor Sentinel, military exercise, background of, 35 208 government under, 32–36, 42, 44, anti-monarchical conspiracy theory, 74, 76, 82, 102, 111, 115, 138, 74, 80 158, 169, 179, 183, 185, 195, see also “lom chao” 203, 205–207, 209–10, 267, 278, “anti-system” forces, 129 280, 305, 309, 329 anti-Thaksin media, 79 reform package proposed by, 89, 95 Anuman Ratchathon, Phraya, 2 absolute monarchy, 22, 192, 221–22, Anuphong Paochinda, 25, 33, 315 269–70 Apichatphong Weerasethakun, see also constitutional monarchy; 184–85 monarchy Appeals Court, 277 absolute poverty, 27, 156, 324 “aristocratic liberalism”, 105 Academy Fantasia, reality show, 93 Army, Thai, 21–22, 25, 35, 43–44, activist monks, 290–92 76–78, 87, 133, 139, 165, 220, agents provocateurs, 294, 299 224, 227, 293, 298, 302, 304, 307, agrarian change, waves of, 232–36 309–10, 323 “ai mong”, 78 psychological warfare unit, 237 Allende, Salvador, 50 restructured, 128 Amara Phongsaphit, 303 Arvizu, Alexander, 253 American Embassy, see U.S. Embassy ASEAN (Association of Southeast ammat (establishment), 21–22, 27, 29, Asian Nations), 166, 202, 204–205, 38, 93, 99, 135, 137–38, -

Organic Crisis, Social Forces, and the Thai State, 1997 – 2010

THE OLD IS DYING AND THE NEW CANNOT BE BORN: ORGANIC CRISIS, SOCIAL FORCES, AND THE THAI STATE, 1997 – 2010 WATCHARABON BUDDHARAKSA PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK POLITICS FEBRUARY 2014 i Abstract This thesis is a study of the crisis-ridden social transition of the Thai state (1997-2010) by analysing the interrelations of social forces in the Thai historical bloc. The thesis argues that the recent political conflict in Thailand that reached its peak in 2010 transcended the conflict between the Thaksin government and its social antagonists, or merely the conflict between the Yellow and the Red Shirt forces. Rather, the organic crisis of the Thai state in the recent decade should be seen as social reflections of the unfinished process of social transition. Furthermore, this transition contains features of ‘crises’, ‘restructuring’, ‘transition’ and ‘other crises’ within the transition. The thesis employs a Gramscian account as a major theoretical framework because it stresses the importance of history, provides tools to analyse configurations of social forces, and offers a combined focus of political, social, and ideological matters. This thesis finds that the street fights and violent government repression in May 2010 was only the tip of the iceberg and the incidents of 2010 themselves did not represent a genuine picture of Thailand’s organic crisis. The crisis, this thesis argues, was not caused only by the Thaksin government and its allies. The Thaksin social force should be seen as a part of a broader social transition in which it acted as a ‘social catalyst’ that brought social change to the Thai state in terms of both political economy and socio- ideological elements. -

Week 4 (21St January 2013 – 27Th January 2013)

Week 4 (21st January 2013 – 27th January 2013) ASEAN Newspapers Issues pertaining to Thailand ‐ politics Number of article(s): 11 Keywords/criteria used for search: Thailand, Thai Search Engine: www.google.com Online newspapers included in search: Borneo Bulletin (Brunei) Brunei Times (Brunei) Phnom Penh Post (Cambodia) Jakarta Post (Indonesia) Jakarta Globe (Indonesia) Vientiane Times (Laos) Vietnam Net (Vietnam) Nhan Dan (Vietnam) The Star (Malaysia) The New Straits Times (Malaysia) The Strait Times (Singapore) The Philippine Inquirer (Philippines) The Japan Times (Japan) China Daily (China) The China Po st (China) Table of Contents THE BRUNEI TIMES 6 22 /J AN. / 2013 – THAI ARMY CHIEF WANTS OFFICERS PROBED FOR HUMAN TRAFFICKING (REUTERS – ALSO PUBLISHED IN THE STRAITS TIMES) 6 ‐ Thai media last Sunday reported that a police investigation had found senior army officers, some with ranks as high as major and colonel, were involved in smuggling Rohingyas from Myanmar into Malaysia via Thailand and that the trafficking had been going on for several years. ‐ Thai Army chief Prayuth Chan‐ocha said last Monday that “…Anyone found to be involved — especially soldiers — will be prosecuted, expelled and charged with a criminal offence,” ‐ Prayuth further noted that some army officers might have got involved in the Rohingya situation because it was "hard not to sympathise with their plight ". THE PHNOM PENH POST 7 22 /J AN. / 2013 HUN SEN BASHES EXTHAI PM 7 ‐ Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen last Monday blasted former Thai Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva and Thai opposition activists for what he said were attempts to use Cambodia as a cudgel to score political points on sensitive issues back home. -

Asia Briefing, Nr. 82: Thailand

Policy Briefing Asia Briefing N°82 Bangkok/Brussels, 22 September 2008 Thailand: Calming the Political Turmoil I. OVERVIEW Complaints of government incompetence or malprac- tice can and should be pursued through democratic and constitutional means, including the courts and Street protests are threatening to bring down the govern- parliament. But the PAD’s proposals for a “new poli- ment led by the People Power Party (PPP) just nine tics” – essentially a reversion to government by the months after it won a decisive victory in general elections. elite, with only 30 per cent of parliamentarians elected Clashes between pro- and anti-government protesters – is profoundly anti-democratic and a recipe for dicta- have left one dead and 42 people injured. Mass action torship. Even the current constitutional settlement – is hurting the economy, including the lucrative – and imposed by the military government last year – gives usually sacrosanct – tourism industry. The replacement the courts and bureaucracy too much power to thwart of Samak Sundaravej with Somchai Wongsawat as prime and undermine an elected government for relatively minister is unlikely to defuse tensions. The immediate minor failings. Samak has already been disqualified need is to restore the rule of law and authority of the from office for an offence which in most countries government – not because it is perfect, but for the sake would be regarded as trivial, and the future of the of stability and democracy. In the medium and longer PPP-led government is under nearly as much threat in term, the priorities must be to resolve political differ- the courts as from the streets. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

Essential reading for anyone interested in ai politics and culture e ai monarchy today is usually presented as both guardian of tradition and the institution to bring modernity and progress to the ai people. It is moreover Saying the seen as protector of the nation. Scrutinizing that image, this volume reviews the fascinating history of the modern monarchy. It also analyses important cultural, historical, political, religious, and legal forces shaping Saying the Unsayable Unsayable the popular image of the monarchy and, in particular, of King Bhumibol Adulyadej. us, the book o ers valuable Monarchy and Democracy insights into the relationships between monarchy, religion and democracy in ailand – topics that, a er the in Thailand September 2006 coup d’état, gained renewed national and international interest. Addressing such contentious issues as ai-style democracy, lése majesté legislation, religious symbolism and politics, monarchical traditions, and the royal su ciency economy, the book will be of interest to a Edited by broad readership, also outside academia. Søren Ivarsson and Lotte Isager www.niaspress.dk Unsayable-pbk_cover.indd 1 25/06/2010 11:21 Saying the UnSayable Ivarsson_Prels_new.indd 1 30/06/2010 14:07 NORDIC INSTITUTE OF ASIAN STUDIES NIAS STUDIES IN ASIAN TOPICS 32 Contesting Visions of the Lao Past Christopher Goscha and Søren Ivarsson (eds) 33 Reaching for the Dream Melanie Beresford and Tran Ngoc Angie (eds) 34 Mongols from Country to City Ole Bruun and Li Naragoa (eds) 35 Four Masters of Chinese Storytelling -

Thailand: Joint CSO Submission to the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (March 2010)

Universal Periodic Review (UPR), Thailand: Joint CSO Submission to the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (March 2010) This joint submission has been prepared in consultation with a number of key Thai CSOsi. It has been endorsed, in whole or part, by the 92 organizations listed in Attachment A. I: Background and framework 1. Thailand has yet to ratify at least two major international Conventions – the Convention on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (CED), which has serious ramifications on the Thai populace, including Thai-Malay Muslims in the three southern-most provinces and elsewhere who disagree with the state, and the Convention on the Protection of the Rights of Migrants Workers and Member of their Families (MWC), which also has far reaching repercussions on Thai citizens and unregistered foreign migrant workers. An estimated 2 million plusii unregistered migrant workers live and work in Thailand with very limited rights and protection. 2. Regarding a number of Conventions that have been ratified by the Thai state, the government has yet to pass organic law to make rights protection a reality, such as laws on torture. As far as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is concerned, the Thai government has submitted initial report on 22 June 2004,iii after a six-year delay. Most notable is the absence of any attempt by the Thai government to disseminate details about the report to the wider public, resulting in little awareness on the issue. On the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the initial report was due on December 5th, 2009,iv but the Royal Thai Government (herein referred to as RTG) has yet to draft it. -

Factbox: Thailand's New Cabinet Line-Up 12:44, February 07, 2008

Factbox: Thailand's new cabinet line-up 12:44, February 07, 2008 The new cabinet line-up of Thailand's first elected government after the Sept. 19 coup that ousted former administration of Thaksin Shinawatra was unveiled after the appointments of the 36 new cabinet members received royal endorsement from the King Bhumibol Adulyadej Wednesday. The full list is as follows (in parenthesis is the political party to which he/she belongs to): Prime Minister and Defense Minister: Samak Sundaravej (People Power Party, or PPP) First Deputy Prime Minister and Education Minister: Somchai Wongsawat (PPP) Deputy Minister and Finance Minister: Surapong Suebwonglee (PPP) Deputy Minister and Industry Minister: Suwit Khunkitti (Puea Pandin, or For the Motherland Party) Deputy Minister: Sanan Kachornparsart (Chart Thai, or Thai Nation Party) Deputy Minister: Sahas Bunditkul (PPP) Deputy Minister and Commerce Minister: Mingkwan Sangsuwan (PPP) PM's Office Ministers: Chusak Sirinil (PPP) Jakrapob Penkair (PPP), also government spokesman Interior Minister: Chalerm Yoobamrung (PPP) Foreign Minister: Noppadol Pattama (PPP) Justice Minister: Sompong Amornwiwat (PPP) Energy Minister: Poonpirom Liptapanlop (Ruam Jai Thai Chart Pattana, or Thais United National Development Party) Agriculture and Coopreatives Minister: Somsak Prisannanuntakul (Chart Thai) Transport Minister: Santi Promphat (PPP) Tourism and Sports Minister: Weerasak Kohsurat (Chart Thai) Public Health Minister: Chaiya Sasomsap (PPP) Science and Technology Minister: Wutthipong Chaisaeng (PPP) Culture -

Policy Statement of the Council of Ministers

UNOFFICIAL TRANSLATION Policy Statement of the Council of Ministers Delivered by Mr. Samak Sundaravej Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Thailand to the National Assembly on Monday 18 February B.E. 2551 (2008) 0 UNOFFICIAL TRANSLATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Announcement on the Appointment ………………… i of the Prime Minister Announcement on the Appointment of Ministers ….. ii Policy Statement of the Government of …………….. 1 Mr. Samak Sundaravej, Prime Minister, to the National Assembly 1. Urgent policies to be carried out in the first year …………... 2 2. Social Policy and Standards of Living …………..………….. 5 3. Economic Policy ……………..……………………………… 8 4. Policies on Land, Natural Resources, and the Environment .. 13 5. Policy on Science, Technology and Innovation …………… 14 6. Foreign Policy and International Economic Policy ………… 14 7. State Security Policy ………………………………………. 15 8. Policy on Good Management and Governance ……………. 16 Annex A ……………………………………………….. 20 Enactment or revision of laws according to the provisions of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand Annex B ……………………………………………….. 22 List of the Cabinet’s Policy Topics in the Administration of State Affairs Compared with the Fundamental Policy Approach in Chapter 5 Of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand 1 UNOFFICIAL TRANSLATION Announcement on the Appointment of the Prime Minister -------------------- Bhumibol Adulyadej, Rex Phrabat Somdet Phra Paramintharamaha Bhumibol Adulyadej has graciously given a Royal Command for the announcement to be made that: Pursuant to the election of the members of the House of Representatives according to the Constitution, the Cabinet administering state affairs having to relinquish their positions, and the Speaker of the House of Representatives having humbly informed His Majesty that the House of Representatives has passed a resolution on 28 January B.E. -

60 Years Oppression Suppression Thailand

Day of global Action for People’s Democracy in Thailand 60 YEARS of OPPRESSION AND SUPPRESSION in THAILAND Compiled by Junya Yimprasert for Action for People’s Democracy in Thailand (ACT4DEM) 19 September 2011 1 CONTENTS PREFACE Political assassinations and extra-judicial killings since 1947 4 Lèse majesté . some recent cases 24 APPENDICES 1. Letter from political prisoners in Bangkok Remand Prison 34 2. Free Somyot Campaign 35 Further information: www.timeupthailand.net 2 PREFACE Will the 9th ‘successful’ military coup against the ‘People’s Assembly’ on 19 September 2006 and the massacre of people in the streets in April-May 2010 lead to a 10th ‘successful’ military coup, with even more loss of civilian life? This document brings together some of the evidence of the fearful tension that underlies the power struggle between the Institution of Monarchy and the Parliament of the People, tension that must be faced with dispassionate reasoning by all sides if the governance of Thailand is to mature in the name of peace and sustainable development. Between these two competing forces there squats the greatly over-grown, hugely self-important Royal Thai Army - playing the game of ‘protecting the Monarch’ from ‘corrupt government’. Our decision, after April-May 2010, to attempt to fill the void of public data about the fallen heroes of the people’s struggle for democracy gradually became an eye-opener - even for the seasoned activist, not just because of the number of top-down political assassinations but because of the consistency of the top-down brutality throughout the 6 decades of the current kingship.