Frame Resonance and Failure in the Thai Red Shirts and Yellow Shirts Movements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

The Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Temple Dispute

International Journal of East Asian Studies, 23(1) (2019), 58-83. Dynamic Roles and Perceptions: The Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Temple Dispute Ornthicha Duangratana1 1 Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand This article is part of the author’s doctoral dissertation, entitled “The Roles and Perceptions of the Thai Ministry of Foreign Affairs through Governmental Politics in the Temple Dispute.” Corresponding Author: Ornthicha Duangratana, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand E-mail: [email protected] Received: 11 Feb 19 Revised: 16 Apr 19 Accepted: 15 May 19 58 Abstract Thailand and Cambodia have long experienced swings between discordant and agreeable relations. Importantly, contemporary tensions between Thailand and Cambodia largely revolve around the disputed area surrounding the Preah Vihear Temple, or Phra Vi- harn Temple (in Thai). The dispute over the area flared after the independence of Cambodia. This situation resulted in the International Court of Justice adjudicating the dispute in 1962. Then, as proactive cooperation with regards to the Thai-Cambodian border were underway in the 2000s, the dispute erupted again and became salient between the years 2008 to 2013. This paper explores the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ (MFA) perceptions towards the overlapping border claim since the Cold War and concentrates on the changes in perceptions in the period from 2008 to 2013 when the Preah Vihear temple dispute rekindled. Moreover, to study their implications on the Thai-Cambodian relations, those perceptions are analyzed in connection to the roles of the MFA in the concurrent Thai foreign-policy apparatus. Under the aforementioned approach, the paper makes the case that the internation- al environment as well as the precedent organizational standpoint significantly compels the MFA’s perceptions. -

Thailand White Paper

THE BANGKOK MASSACRES: A CALL FOR ACCOUNTABILITY ―A White Paper by Amsterdam & Peroff LLP EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For four years, the people of Thailand have been the victims of a systematic and unrelenting assault on their most fundamental right — the right to self-determination through genuine elections based on the will of the people. The assault against democracy was launched with the planning and execution of a military coup d’état in 2006. In collaboration with members of the Privy Council, Thai military generals overthrew the popularly elected, democratic government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, whose Thai Rak Thai party had won three consecutive national elections in 2001, 2005 and 2006. The 2006 military coup marked the beginning of an attempt to restore the hegemony of Thailand’s old moneyed elites, military generals, high-ranking civil servants, and royal advisors (the “Establishment”) through the annihilation of an electoral force that had come to present a major, historical challenge to their power. The regime put in place by the coup hijacked the institutions of government, dissolved Thai Rak Thai and banned its leaders from political participation for five years. When the successor to Thai Rak Thai managed to win the next national election in late 2007, an ad hoc court consisting of judges hand-picked by the coup-makers dissolved that party as well, allowing Abhisit Vejjajiva’s rise to the Prime Minister’s office. Abhisit’s administration, however, has since been forced to impose an array of repressive measures to maintain its illegitimate grip and quash the democratic movement that sprung up as a reaction to the 2006 military coup as well as the 2008 “judicial coups.” Among other things, the government blocked some 50,000 web sites, shut down the opposition’s satellite television station, and incarcerated a record number of people under Thailand’s infamous lèse-majesté legislation and the equally draconian Computer Crimes Act. -

War of Words: Isan Redshirt Activists and Discourses of Thai Democracy

This is a repository copy of War of words: Isan redshirt activists and discourses of Thai democracy. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/104378/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Alexander, ST and McCargo, D orcid.org/0000-0002-4352-5734 (2016) War of words: Isan redshirt activists and discourses of Thai democracy. South East Asia Research, 24 (2). pp. 222-241. ISSN 0967-828X https://doi.org/10.1177/0967828X16649045 © 2016, SOAS. This is an author produced version of a paper published in South East Asia Research. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ War of Words War of Words: Isan Redshirt Activists and Discourses of Thai Democracy Abstract Thai grassroots activists known as ‘redshirts’ (broadly aligned with former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra) have been characterized accordingly to their socio-economic profile, but despite pioneering works such as Buchanan (2013), Cohen (2012) and Uenaldi (2014), there is still much to learn about how ordinary redshirts voice their political stances. -

Thailand: the Evolving Conflict in the South

THAILAND: THE EVOLVING CONFLICT IN THE SOUTH Asia Report N°241 – 11 December 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. STATE OF THE INSURGENCY .................................................................................... 2 A. THE INSURGENT MOVEMENT ....................................................................................................... 2 B. PATTERNS OF VIOLENCE .............................................................................................................. 4 C. MORE CAPABLE MILITANTS ........................................................................................................ 5 D. 31 MARCH BOMBINGS ................................................................................................................. 6 E. PLATOON-SIZED ATTACKS ........................................................................................................... 6 III. THE SECURITY RESPONSE ......................................................................................... 8 A. THE NATIONAL SECURITY POLICY FOR THE SOUTHERN BORDER PROVINCES, 2012-2014 ......... 10 B. SPECIAL LAWS ........................................................................................................................... 10 C. SECURITY FORCES .................................................................................................................... -

Military Brotherhood Between Thailand and Myanmar: from Ruling to Governing the Borderlands

1 Military Brotherhood between Thailand and Myanmar: From Ruling to Governing the Borderlands Naruemon Thabchumphon, Carl Middleton, Zaw Aung, Surada Chundasutathanakul, and Fransiskus Adrian Tarmedi1, 2 Paper presented at the 4th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Research Network conference “Activated Borders: Re-openings, Ruptures and Relationships”, 8-10 December 2014 Southeast Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong 1. Introduction Signaling a new phase of cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar, on 9 October 2014, Thailand’s new Prime Minister, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha took a two-day trip to Myanmar where he met with high-ranked officials in the capital Nay Pi Taw, including President Thein Sein. That this was Prime Minister Prayuth’s first overseas visit since becoming Prime Minister underscored the significance of Thailand’s relationship with Myanmar. During their meeting, Prime Minister Prayuth and President Thein Sein agreed to better regulate border areas and deepen their cooperation on border related issues, including on illicit drugs, formal and illegal migrant labor, including how to more efficiently regulate labor and make Myanmar migrant registration processes more efficient in Thailand, human trafficking, and plans to develop economic zones along border areas – for example, in Mae 3 Sot district of Tak province - to boost trade, investment and create jobs in the areas . With a stated goal of facilitating border trade, 3 pairs of adjacent provinces were named as “sister provinces” under Memorandums of Understanding between Myanmar and Thailand signed by the respective Provincial governors during the trip.4 Sharing more than 2000 kilometer of border, both leaders reportedly understood these issues as “partnership matters for security and development” (Bangkok Post, 2014). -

Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011

Thai Netizen Network Annual Report: Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011 An annual report of Thai Netizen Network includes information, analysis, and statement of Thai Netizen Network on rights, freedom, participation in policy, and Thai internet culture in 2011. Researcher : Thaweeporn Kummetha Assistant researcher : Tewarit Maneechai and Nopphawhan Techasanee Consultant : Arthit Suriyawongkul Proofreader : Jiranan Hanthamrongwit Accounting : Pichate Yingkiattikun, Suppanat Toongkaburana Original Thai book : February 2012 first published English translation : August 2013 first published Publisher : Thai Netizen Network 672/50-52 Charoen Krung 28, Bangrak, Bangkok 10500 Thailand Thainetizen.org Sponsor : Heinrich Böll Foundation 75 Soi Sukhumvit 53 (Paidee-Madee) North Klongton, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand The editor would like to thank you the following individuals for information, advice, and help throughout the process: Wason Liwlompaisan, Arthit Suriyawongkul, Jiranan Hanthamrongwit, Yingcheep Atchanont, Pichate Yingkiattikun, Mutita Chuachang, Pravit Rojanaphruk, Isriya Paireepairit, and Jon Russell Comments and analysis in this report are those of the authors and may not reflect opinion of the Thai Netizen Network which will be stated clearly Table of Contents Glossary and Abbreviations 4 1. Freedom of Expression on the Internet 7 1.1 Cases involving the Computer Crime Act 7 1.2 Internet Censorship in Thailand 46 2. Internet Culture 59 2.1 People’s Use of Social Networks 59 in Political Movements 2.2 Politicians’ Use of Social -

Myanmar: the Key Link Between

ADBI Working Paper Series Myanmar: The Key Link between South Asia and Southeast Asia Hector Florento and Maria Isabela Corpuz No. 506 December 2014 Asian Development Bank Institute Hector Florento and Maria Isabela Corpuz are consultants at the Office of Regional Economic Integration, Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. In this paper, “$” refers to US dollars. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Florento, H., and M. I. Corpuz. 2014. Myanmar: The Key Link between South Asia and Southeast Asia. ADBI Working Paper 506. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: http://www.adbi.org/working- paper/2014/12/12/6517.myanmar.key.link.south.southeast.asia/ Please contact the authors for information about this paper. -

Board of Editors

2020-2021 Board of Editors EXECUTIVE BOARD Editor-in-Chief KATHERINE LEE Managing Editor Associate Editor KATHRYN URBAN KYLE SALLEE Communications Director Operations Director MONICA MIDDLETON CAMILLE RYBACKI KOCH MATTHEW SANSONE STAFF Editors PRATEET ASHAR WENDY ATIENO KEYA BARTOLOMEO Fellows TREVOR BURTON SABRINA CAMMISA PHILIP DOLITSKY DENTON COHEN ANNA LOUGHRAN SEAMUS LOVE IRENE OGBO SHANNON SHORT PETER WHITENECK FACULTY ADVISOR PROFESSOR NANCY SACHS Thailand-Cambodia Border Conflict: Sacred Sites and Political Fights Ihechiluru Ezuruonye Introduction “I am not the enemy of the Thai people. But the [Thai] Prime Minister and the Foreign Minister look down on Cambodia extremely” He added: “Cambodia will have no happiness as long as this group [PAD] is in power.” - Cambodian PM Hun Sen Both sides of the border were digging in their heels; neither leader wanted to lose face as doing so could have led to a dip in political support at home.i Two of the most common drivers of interstate conflict are territorial disputes and the politicization of deep-seated ideological ideals such as religion. Both sources of tension have contributed to the emergence of bloody conflicts throughout history and across different regions of the world. Therefore, it stands to reason, that when a specific geographic area is bestowed religious significance, then conflict is particularly likely. This case study details the territorial dispute between Thailand and Cambodia over Prasat (meaning ‘temple’ in Khmer) Preah Vihear or Preah Vihear Temple, located on the border between the two countries. The case of the Preah Vihear Temple conflict offers broader lessons on the social forces that make religiously significant territorial disputes so prescient and how national governments use such conflicts to further their own political agendas. -

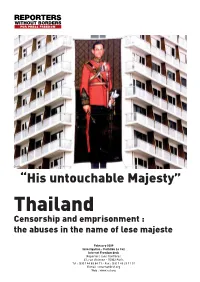

Thailand Censorship and Emprisonment : the Abuses in the Name of Lese Majeste

© AFP “His untouchable Majesty” Thailand Censorship and emprisonment : the abuses in the name of lese majeste February 2009 Investigation : Clothilde Le Coz Internet Freedom desk Reporters sans frontières 47, rue Vivienne - 75002 Paris Tel : (33) 1 44 83 84 71 - Fax : (33) 1 45 23 11 51 E-mail : [email protected] Web : www.rsf.org “But there has never been anyone telling me "approve" because the King speaks well and speaks correctly. Actually I must also be criticised. I am not afraid if the criticism concerns what I do wrong, because then I know. Because if you say the King cannot be criticised, it means that the King is not human.”. Rama IX, king of Thailand, 5 december 2005 Thailand : majeste and emprisonment : the abuses in name of lese Censorship 1 It is undeniable that King Bhumibol According to Reporters Without Adulyadej, who has been on the throne Borders, a reform of the laws on the since 5 May 1950, enjoys huge popularity crime of lese majeste could only come in Thailand. The kingdom is a constitutio- from the palace. That is why our organisa- nal monarchy that assigns him the role of tion is addressing itself directly to the head of state and protector of religion. sovereign to ask him to find a solution to Crowned under the dynastic name of this crisis that is threatening freedom of Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, born in expression in the kingdom. 1927, studied in Switzerland and has also shown great interest in his country's With a king aged 81, the issues of his suc- agricultural and economic development. -

POLITICAL PARTY FINANCE REFORM and the RISE of DOMINANT PARTY in EMERGING DEMOCRACIES: a CASE STUDY of THAILAND by Thitikorn

POLITICAL PARTY FINANCE REFORM AND THE RISE OF DOMINANT PARTY IN EMERGING DEMOCRACIES: A CASE STUDY OF THAILAND By Thitikorn Sangkaew Submitted to Central European University - Private University Department of Political Science In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Supervisor: Associate Professor Matthijs Bogaards CEU eTD Collection Vienna, Austria 2021 ABSTRACT The dominant party system is a prominent phenomenon in emerging democracies. One and the same party continues to govern the country for a certain period through several consecutive multi-party elections. Literature on this subject has tended to focus on one (set) of explanation(s) deduced from electoral model, but the way a certain party dominates electoral politics at the outset of democratization remains neglected. Alternatively, this thesis highlights the importance of the party finance model, arguing that it can complement the understanding of one-party dominance. To evaluate this argument, the thesis adopts a complementary theories approach of the congruence analysis as its strategy. A systematic empirical analysis of the Thai Rak Thai party in Thailand provides support for the argument of the thesis. The research findings reveal that the party finance regime can negatively influence the party system. Instead of generating equitable party competition and leveling the playing field, it favors major parties while reduces the likelihood that smaller parties are more institutionalized and competed in elections. Moreover, the party finance regulations are not able to mitigate undue influence arising from business conglomerates. Consequently, in combination with electoral rules and party regulations, the party finance regime paves the way for the rise and consolidation of one- party dominance. -

Her Royal Highness Princess Bajrakitiyabha Narendiradebyavati

Her Royal Highness Princess Bajrakitiyabha Narendiradebyavati Her Royal Highness Princess Bajrakitiyabha Narendiradebyavati (Thai: พัชรกิติยาภา นเรนทิราเทพยวดี, RTGS: Phatchara Kitiyapha Narenthira Thepphayawati, also known as Princess Pa or Patty, born 7 December 1978) is a Thai diplomat and princess of Thailand, the first grandchild of King Bhumibol and Queen Sirikit of Thailand, and the only one of the seven children of King Maha Vajiralongkorn born to his first wife Princess Soamsawali. Early life and education Princess Bajrakitiyabha was born on 7 December 1978 at Amphorn Sathan Residential Hall, Dusit Palace in Bangkok, She is eldest child and first daughter of Vajiralongkorn and his first wife princess Soamsawali, She studied at the all-girls Rajini School when she was in elementary and junior high school. She moved to England and began her secondary education first at Heathfield School in Ascot, finishing at the Chitralada School. Princess Bajrakitiyabha received a LL.B. degree from Thammasat University, as well a B.A. degree in International Relations from Sukhothai Thammatirat University, both in 2000. She subsequently obtained a LL.M. degree from Cornell Law School in 2002 and a J.S.D. degree from Cornell University in 2005. On 12 May 2012, she was awarded an honorary LL.D. degree from IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. On completion of her doctorate Princess Bajrakitiyabha worked briefly at the Thai Permanent Mission to the United Nations, in New York, before returning to Thailand. In September 2006, she was appointed Attorney in the Office of the Attorney General in Bangkok, and is currently appointed to Office of the Attorney General of Udon Thani Province.