Report of the Sixth Annual Round Table Meeting on Linguistics and Language Teaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Person Meets Word Part 1: Personalism in the Language

WTJ 77 (2015): 355–77 WHERE PERSON MEETS WORD PART 1: PERSONALISM IN THE LANGUAGE THEORY OF KENNETH L. PIKE Pierce Taylor Hibbs I. Introduction eformed theology has always championed the Trinity as the beating heart of the Christian faith. This is true not just of the mainstay his- torical Reformers, Luther and Calvin, but also of Dutch Calvinism, Old R 1 Princeton, and the Westminster heritage. Certainly, Calvin and Melanchthon were not alone in claiming that “God’s triunity was that which distinguished the true and living God from idols.”2 The true God is the Trinity. Out of this tradition emerged Cornelius Van Til and his insistence that the self-contained ontological Trinity be the basis of all human experience and knowledge.3 He claimed that “if we are to have coherence in our experience, Pierce Hibbs currently serves as the Assistant Director of the Center for Theological Writing at Westminster Theological Seminary. 1 On Luther, see David Lumpp, “Returning to Wittenberg: What Martin Luther Teaches Today’s Theologians on the Holy Trinity,” CTQ 67 (2003): 232, 233–34; and Mickey Mattox, “From Faith to the Text and Back Again: Martin Luther on the Trinity in the Old Testament,” ProEccl 15 (2006): 292. On Calvin, see T. F. Torrance, “Calvin’s Doctrine of the Trinity,” CTJ 25 (1990): 166. For an example of the Dutch Calvinist view, see Herman Bavinck, Reformed Dogmatics, ed. John Bolt, trans. John Vriend, 4 vols. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2003–2008), 2:279, 329. For Old Princeton, see Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2013), 1:442; and B. -

Artist Title Count PURPLE DISCO MACHINE FEAT. MOSS KENA & THEFIREWORKS KNOCKS 92 LEONY FADED LOVE 83 ONEREPUBLIC RUN 82 ATB FT

Artist Title Count PURPLE DISCO MACHINE FEAT. MOSS KENA & THEFIREWORKS KNOCKS 92 LEONY FADED LOVE 83 ONEREPUBLIC RUN 82 ATB FT. TOPIC & A7S YOUR LOVE 81 JUSTIN BIEBER FT. DANIEL CAESAR PEACHES 81 COLDPLAY HIGHER POWER 80 IMAGINE DRAGONS FOLLOW YOU 80 OLIVIA RODRIGO GOOD 4 YOU 80 REGARD X TROYE SIVAN X TATE MCRAE YOU 79 ALVARO SOLER MAGIA 74 RITON X NIGHTCRAWLERS FRIDAY 74 LOST FREQUENCES RISE 70 JONAS BLUE FT. AVA SOMETHING STUPID 69 THE WEEKND SAVE YOUR TEARS 69 KUNGS NEVER GOING HOME 68 ED SHEERAN BAD HABITS 68 JUSTIN WELLINGTON FEAT. SMALL JAM IKO IKO 67 MAJESTIC X BONEY M. RASPUTIN 67 ROBIN SCHULZ FT. FELIX JAEHN & ALIDA ONE MORE TIME 66 RAG'N'BONE MAN ALL YOU EVER WANTED 64 DUA LIPA LOVE AGAIN 63 JOEL CORRY FT. RAYE & DAVID GUETTA BED 63 JASON DERULO & NUKA LOVE NOT WAR 62 MEDUZA FT. DERMOT KENNEDY PARADISE 59 AVA MAX MY HEAD & MY HEART 58 DUA LIPA WE'RE GOOD 57 MARTIN GARRIX FEAT. BONO & THE EDGE WE ARE THE PEOPLE 57 JOEL CORRY HEAD AND HEART 56 CALVIN HARRIS FT. TOM GRENNAN BY YOUR SIDE 56 DOJA CAT FEAT. SZA KISS ME MORE 56 PINK ALL I KNOW SO FAR 54 OFENBACH FT. LAGIQUE WASTED LOVE 53 PINK + WILLOW SAGE HART COVER ME IN SUNSHINE 53 MALARKEY SHACKLES (PRAISE YOU) 50 MASTER KG FT. NOMCEBO JERUSALEMA 49 SIA & DAVID GUETTA FLOATING THROUGH SPACE 48 SUPER-HI & NEEKA FOLLOWING THE SUN 48 ALVARO SOLER FT. CALI Y EL DANDEE MANANA 44 MARCO MENGONI MA STASERA 42 AVA MAX EVERYTIME I CRY 41 TATE MCRAE YOU BROKE ME FIRST [LUCA SCHREINER41 REMIX] MAROON 5 LOST 40 OFENBACH & QUARTERHEAD HEAD SHOULDERS KNEES & TOES 38 PS1 FT. -

Éducation Et Didactique, 5-3 | 2011 a Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/Emic Distin

Éducation et didactique 5-3 | 2011 Varia A Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/Emic Distinction Christina Hahn, Jane Jorgenson and Wendy Leeds-Hurwitz Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/educationdidactique/1167 DOI: 10.4000/educationdidactique.1167 ISSN: 2111-4838 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 30 December 2011 Number of pages: 145-154 ISBN: 978-2-7535-1832-2 ISSN: 1956-3485 Electronic reference Christina Hahn, Jane Jorgenson and Wendy Leeds-Hurwitz, « A Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/Emic Distinction », Éducation et didactique [Online], 5-3 | 2011, Online since 30 December 2013, connection on 09 December 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ educationdidactique/1167 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/educationdidactique.1167 This text was automatically generated on 9 December 2020. Tous droits réservés A Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/Emic Distin... 1 A Curious Mixture of Passion and Reserve”: Understanding the Etic/ Emic Distinction Christina Hahn, Jane Jorgenson and Wendy Leeds-Hurwitz 1 The title of this chapter alludes to the complex requirements placed on ethnographic researchers who maintain multiple roles as both insiders and outsiders to the social settings they study. When in the role of insiders, researchers try to apprehend the contextualized meanings of people’s experiences within specific locales, while in their role as outsiders, they seek to identify commonalities across different locales. Clyde Kluckhohn alluded to this tension when he proposed that « the hallmark of the good anthropologist must be a curious mixture of passion and reserve » (1957, pp. -

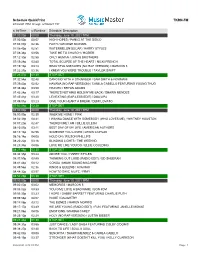

Schedule Quickprint TKRN-FM

Schedule QuickPrint TKRN-FM 6/10/2021 7PM through 6/10/2021 11P s: AirTime s: Runtime Schedule: Description 07:00:00p 00:00 Thursday, June 10, 2021 7PM 07:00:00p 03:07 HIGH HOPES / PANIC! AT THE DISCO 07:03:07p 02:36 FAITH / GEORGE MICHAEL 07:05:43p 02:51 WATERMELON SUGAR / HARRY STYLES 07:08:34p 03:56 TAKE ME TO CHURCH / HOZIER 07:12:30p 02:58 ONLY HUMAN / JONAS BROTHERS 07:15:28p 03:45 TOTAL ECLIPSE OF THE HEART / NICKI FRENCH 07:19:13p 03:14 BEAUTIFUL MISTAKES (NO RAP VERSION) / MAROON 5 07:22:27p 03:36 I KNEW YOU WERE TROUBLE / TAYLOR SWIFT 07:26:07p 03:30 STOP-SET 07:32:54p 02:48 DANCING WITH A STRANGER / SAM SMITH & NORMANI 07:35:42p 02:52 HAVANA (NO RAP VERSION) / CAMILA CABELLO FEATURING YOUNG THUG 07:38:34p 03:50 HEAVEN / BRYAN ADAMS 07:42:24p 03:17 THERE'S NOTHING HOLDIN' ME BACK / SHAWN MENDES 07:45:41p 03:20 LEVITATING (RAP-LESS EDIT) / DUA LIPA 07:49:01p 03:23 GIVE YOUR HEART A BREAK / DEMI LOVATO 07:52:24p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:00:00p 00:00 Thursday, June 10, 2021 8PM 08:00:00p 02:39 WALK ME HOME / PINK 08:02:39p 04:41 I WANNA DANCE WITH SOMEBODY (WHO LOVES ME) / WHITNEY HOUSTON 08:07:20p 02:47 THEREFORE I AM / BILLIE EILESH 08:10:07p 03:11 BEST DAY OF MY LIFE / AMERICAN AUTHORS 08:13:18p 02:56 SOMEONE YOU LOVED / LEWIS CAPALDI 08:16:14p 04:08 HOLD ON / WILSON PHILLIPS 08:20:22p 03:16 BLINDING LIGHTS / THE WEEKND 08:23:38p 04:06 LOVE ME LIKE YOU DO / ELLIE GOULDING 08:27:48p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:34:35p 03:24 ADORE YOU / HARRY STYLES 08:37:59p 03:45 THINKING OUT LOUD (RADIO EDIT) / ED SHEERAN 08:41:44p 04:12 CONGA / MIAMI SOUND MACHINE 08:45:56p 02:36 KINGS & QUEENS / AVA MAX 08:48:32p 03:57 HOW TO SAVE A LIFE / FRAY 08:52:29p 03:30 STOP-SET 09:00:00p 00:00 Thursday, June 10, 2021 9PM 09:00:00p 03:02 MEMORIES / MAROON 5 09:03:02p 03:33 YOU GIVE LOVE A BAD NAME / BON JOVI 09:06:35p 03:23 I HOPE / GABBY BARRETT FEATURING CHARLIE PUTH 09:09:58p 04:07 HOME / DAUGHTRY 09:14:05p 03:12 THE BONES / MAREN MORRIS 09:17:17p 03:49 WE ARE YOUNG (RADIO EDIT) / FUN. -

The Creative Fight Create Your Best Work and Live the Life You Imagine

THE CREATIVE FIGHT CREATE YOUR BEST WORK AND LIVE THE LIFE YOU IMAGINE CHRIS ORWIG THE CREATIVE FIGHT CREATE YOUR BEST WORK AND LIVE THE LIFE YOU IMAGINE CHRIS ORWIG THE CREATIVE FIGHT: CREATE YOUR BEST WORK AND LIVE THE LIFE YOU IMAGINE Chris Orwig Peachpit Press www.peachpit.com To report errors, please send a note to [email protected] Peachpit Press is a division of Pearson Education. Copyright © 2016 by Chris Orwig All images copyright © 2016 by Chris Orwig Project Editor: Valerie Witte Production Editor: David Van Ness Copy Editor: Scout Festa Proofreader: Liz Welch Composition: Kim Scott, Bumpy Design Indexer: James Minkin Cover Image: John Kelsey / Chris Orwig Cover Design: Cybele Grandjean Interior Design: Cybele Grandjean Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For information on getting permission for reprints and excerpts, contact [email protected]. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As Is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of the book, neither the author nor Peachpit shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss, damage, or injury caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the instructions con- tained in this book or by the computer software and hardware products described in it. Trademarks Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their prod- ucts are claimed as trademarks. -

Schedule Quickprint TKRN-FM

Schedule QuickPrint TKRN-FM 7/22/2021 7PM through 7/22/2021 11P s: AirTime s: Runtime Schedule: Description 07:00:00p 00:00 Thursday, July 22, 2021 7PM 07:00:00p 02:58 DON'T START NOW / DUA LIPA 07:02:58p 03:59 EVERYBODY WANTS TO RULE THE WORLD / TEARS FOR FEARS 07:06:57p 03:30 WILLOW / TAYLOR SWIFT 07:10:27p 03:15 SHUT UP AND DANCE / WALK THE MOON 07:13:42p 02:28 HOLY (NO RAP VERSION) / JUSTIN BIEBER 07:16:10p 04:17 VOGUE (SINGLE) / MADONNA 07:20:27p 03:28 BEFORE YOU GO / LEWIS CAPALDI 07:23:55p 03:44 FIREWORK / KATY PERRY 07:27:43p 03:30 STOP-SET 07:34:30p 02:39 WALK ME HOME / PINK 07:37:09p 03:55 A THOUSAND YEARS (RADIO EDIT) / CHRISTINA PERRI 07:41:04p 04:38 HOLD ME NOW / THOMPSON TWINS 07:45:42p 02:43 YOU BROKE ME FIRST / TATE MC RAE 07:48:25p 04:01 DON'T STOP THE MUSIC (RADIO EDIT) / RIHANNA 07:52:26p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:00:00p 00:00 Thursday, July 22, 2021 8PM 08:00:00p 02:58 TRAMPOLINE / SHAED 08:02:58p 04:04 TAKE MY BREATH AWAY / BERLIN 08:07:02p 03:16 BLINDING LIGHTS / THE WEEKND 08:10:18p 03:52 WATER UNDER THE BRIDGE / ADELE 08:14:10p 03:00 SAVAGE LOVE / JAWSH 365 X JASON DERULO X BTS 08:17:10p 04:23 TRULY MADLY DEEPLY / SAVAGE GARDEN 08:21:33p 02:36 KINGS & QUEENS / AVA MAX 08:24:09p 03:58 NO ONE / ALICIA KEYS 08:28:11p 03:30 STOP-SET 08:34:58p 03:28 INTENTIONS / JUSTIN BIEBER FEATURING QUAVO 08:38:26p 03:25 HAPPY / PHARRELL WILLIAMS 08:41:51p 04:03 WILL YOU STILL LOVE ME? / CHICAGO 08:45:54p 03:14 BEAUTIFUL MISTAKES (NO RAP VERSION) / MAROON 5 08:49:08p 03:21 USE SOMEBODY / KINGS OF LEON 08:52:29p 03:30 STOP-SET 09:00:00p 00:00 -

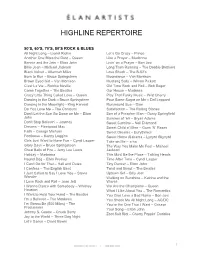

Highline Repertoire

HIGHLINE REPERTOIRE 50’S, 60’S, 70’S, 80’S ROCK & BLUES All Night Long – Lionel Richie Let’s Go Crazy – Prince Another One Bites the Dust – Queen Like a Prayer – Madonna Bennie and the Jets – Elton John Livin’ on a Prayer – Bon Jovi Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Long Train Running – The Doobie Brothers Black Velvet – Allannah Miles Love Shack – The B-52’s Born to Run – Bruce Springsteen Moondance – Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Mustang Sally – Wilson Pickett C’est La Vie – Robbie Neville Old Time Rock and Roll – Bob Seger Come Together – The Beatles Our House – Madness Crazy Little Thing Called Love – Queen Play That Funky Music – Wild Cherry Dancing in the Dark – Bruce Springsteen Pour Some Sugar on Me – Def Leppard Dancing in the Moonlight – King Harvest Runaround Sue – Dion Do You Love Me – The Contours Satisfaction – The Rolling Stones Don’t Let the Sun Go Down on Me – Elton Son of a Preacher Man – Dusty Springfield John Summer of ’69 – Bryan Adams Don’t Stop Believin’ – Journey Sweet Caroline – Neil Diamond Dreams – Fleetwood Mac Sweet Child o’ Mine – Guns ‘N’ Roses Faith – George Michael Sweet Dreams – Eurythmics Footloose – Kenny Loggins Sweet Home Alabama – Lynyrd Skynyrd Girls Just Want to Have Fun – Cyndi Lauper Take on Me – a-ha Glory Days – Bruce Springsteen The Way You Make Me Feel – Michael Great Balls of Fire – Jerry Lee Lewis Jackson Holiday – Madonna This Must Be the Place – Talking Heads Hound Dog – Elvis Presley Time After Time – Cyndi Lauper I Can’t Go for That – Hall and Oates Tiny Dancer – Elton John -

Handbook-Of-Semiotics.Pdf

Page i Handbook of Semiotics Page ii Advances in Semiotics THOMAS A. SEBEOK, GENERAL EDITOR Page iii Handbook of Semiotics Winfried Nöth Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Page iv First Paperback Edition 1995 This Englishlanguage edition is the enlarged and completely revised version of a work by Winfried Nöth originally published as Handbuch der Semiotik in 1985 by J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart. ©1990 by Winfried Nöth All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Nöth, Winfried. [Handbuch der Semiotik. English] Handbook of semiotics / Winfried Nöth. p. cm.—(Advances in semiotics) Enlarged translation of: Handbuch der Semiotik. Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. ISBN 0253341205 1. Semiotics—handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Communication —Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. II. Series. P99.N6513 1990 302.2—dc20 8945199 ISBN 0253209595 (pbk.) CIP 4 5 6 00 99 98 Page v CONTENTS Preface ix Introduction 3 I. History and Classics of Modern Semiotics History of Semiotics 11 Peirce 39 Morris 48 Saussure 56 Hjelmslev 64 Jakobson 74 II. Sign and Meaning Sign 79 Meaning, Sense, and Reference 92 Semantics and Semiotics 103 Typology of Signs: Sign, Signal, Index 107 Symbol 115 Icon and Iconicity 121 Metaphor 128 Information 134 Page vi III. -

Angol-Magyar Nyelvészeti Szakszótár

PORKOLÁB - FEKETE ANGOL- MAGYAR NYELVÉSZETI SZAKSZÓTÁR SZERZŐI KIADÁS, PÉCS 2021 Porkoláb Ádám - Fekete Tamás Angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótár Szerzői kiadás Pécs, 2021 Összeállították, szerkesztették és tördelték: Porkoláb Ádám Fekete Tamás Borítóterv: Porkoláb Ádám A tördelés LaTeX rendszer szerint, az Overleaf online tördelőrendszerével készült. A felhasznált sablon Vel ([email protected]) munkája. https://www.latextemplates.com/template/dictionary A szótárhoz nyújtott segítő szándékú megjegyzéseket, hibajelentéseket, javaslatokat, illetve felajánlásokat a szótár hagyományos, nyomdai úton történő előállítására vonatkozóan az [email protected] illetve a [email protected] e-mail címekre várjuk. Köszönjük szépen! 1. kiadás Szerzői, elektronikus kiadás ISBN 978-615-01-1075-2 El˝oszóaz els˝okiadáshoz Üdvözöljük az Olvasót! Magyar nyelven már az érdekl˝od˝oközönség hozzáférhet német–magyar, orosz–magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakhoz, ám a modern id˝ok tudományos világnyelvéhez, az angolhoz még nem készült nyelvészeti célú szak- szótár. Ennek a több évtizedes hiánynak a leküzdésére vállalkoztunk. A nyelvtudo- mány rohamos fejl˝odéseés differenciálódása tovább sürgette, hogy elkészítsük az els˝omagyar-angol és angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárakat. Jelen kötetben a kétnyelv˝unyelvészeti szakszótárunk angol-magyar részét veheti kezébe az Olvasó. Tervünk azonban nem el˝odöknélküli vállalkozás: tudomásunk szerint két nyelvészeti csoport kísérelt meg a miénkhez hasonló angol-magyar nyelvészeti szakszótárat létrehozni. Az els˝opróbálkozás -

Theme and the Function of the Verb in Palestinian Arabic Narrative Discourse

THEME AND THE FUNCTION OF THE VERB IN PALESTINIAN ARABIC NARRATIVE DISCOURSE BY ILHAM NAYEF ABU-GHAZALEH A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1983 , To my sister SHADYIA, who refused to continue her studies at Cairo University after the final occupation of Palestine in 1967 - She said, before she was killed at the age of -nineteen "WHAT IS THE USE OF A UNIVERSITY DEGREE FOR A PALESTINIAN WHEN HE HAS NO WALL TO HANG IT ON?" . ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My thankfulness to the head of my committee, Dr. Chauncey Chu, is limitless. I am greatly indebted to him for his tireless devotion and generosity in giving of his valuable time to crystallize this work. His kind and patient encourage- ment has been an important factor in my academic growth. My gratitude also goes to the rest of the members of my committee. Dr. Alice Faber's comments, guidance and sup- port sharpened my perception in this analysis. Dr. Bill Sullivan enriched my analysis by helping me see other sides to it. Dr. Robert de Beaugrande always enabled me to put things into perspective through his discussions, concern and encouragement. My discussions with Dr. Rene LeMarchand were of great importance to me. My greatest thanks and love go to my home university, Birzeit, for providing me with this opportunity for growth and enrichment. The difficulties they were enduring while I was far from them constituted a heavy part of my personal suffering To all my friends in Gainesville, in the United States, and at home, go my unlimited love and gratitude. -

What's in This Issue

In Focus June 2015 Edition: 06/2015 What’s In This Issue Content Pg. CLUB MEETINGS Photo Group Diary .............................................. 1 2nd and 4th Tuesday of Each Month Dates For Your Diary ......................................... 2 at 7.30pm Tuesday, May 12 th 2015 ...................................... 3 FIGTREE HEIGHTS PRIMARY SCHOOL Photographer’s Rights in Australia. .................. 5 th St Georges Avenue & Lewis Drive Tuesday, May 26 2015 ...................................... 5 FIGTREE POINTSCORES: June 2015 ............................. 10 Vehicle entrance via Lewis Drive Colour Prints ................................................... 10 FIGTREE Monochrome Prints ......................................... 11 UBD Map: 34 Ref: P6 EDI .................................................................. 11 Small Prints ..................................................... 11 2015 Competition: July ..................................... 11 Future Cameras Will Make Living Photographs Reality ................................................................. 12 Club Address: P.O Box 193 FIGTREE, NSW. 2525 The Techno Shop ............................................... 13 Quick Tips .......................................................... 14 Phone Contact: 0457 415598 Photo Group Diary Club Website: June 2015 http://www.wollongongcameraclub.com Tues 9th “Wedding and Social Photography” Enquiries : with Anna Fitzgerald [email protected] Tues 16 th EDI Competition Entry Closing Date. Competition Entries -

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2007

San Diego Public Library New Additions September 2007 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities Biographies 100 - Philosophy & Psychology California Room 200 - Religion CD-ROMs 300 - Social Sciences Compact Discs 400 - Language DVD Videos/Videocassettes 500 - Science eBooks 600 - Technology Fiction 700 - Art Foreign Languages 800 - Literature Genealogy Room 900 - Geography & History Graphic Novels Audiocassettes Large Print Audiovisual Materials Fiction Call # Author Title [SCI-FI] FIC/ADAMS Adams, Douglas The ultimate hitchhiker's guide FIC/ALLEN Allen, Woody. Side effects. FIC/ANDERS Anders, Donna. Night stalker FIC/ANDREWS Andrews, Mary Kay Hissy fit FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey Cat o'nine tales and other stories FIC/ARGUEDAS Arguedas, José María Yawar fiesta FIC/ASIMOV Asimov, Isaac The complete robot FIC/ASTON Aston, Elizabeth. Mr. Darcy's daughters [MYST] FIC/ATKINSON Atkinson, Kate. One good turn FIC/ATWOOD Atwood, Margaret Eleanor The handmaid's tale FIC/AUCHINCLOSS Auchincloss, Louis. East Side story FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane Pride and prejudice FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane Sense and sensibility FIC/AYLMER Aylmer, Janet. Darcy's story FIC/BAGGOTT Baggott, Julianna. Girl talk FIC/BALDACCI Baldacci, David. Simple genius FIC/BALDACCI Baldacci, David. The collectors [MYST] FIC/BARNARD Barnard, Robert. A murder in Mayfair FIC/BARNES Barnes, Julian. Arthur & George FIC/BARON Baron, Aileen Garsson. The gold of Thrace FIC/BARRY Barry, Maxx. Jennifer Government [MYST] FIC/BASS Bass, Jefferson. Flesh and bone FIC/BATTLES Battles, Brett. The cleaner [MYST] FIC/BEATON Beaton, M. C. Agatha Raisin and the terrible tourist [MYST] FIC/BEATON Beaton, M. C. Love, lies and liquor FIC/BELLE Belle, Jennifer Going down FIC/BERG Berg, Elizabeth.