UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99q9f2k0 Author Bailony, Reem Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Reem Bailony 2015 © Copyright by Reem Bailony 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 by Reem Bailony Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor James L. Gelvin, Chair This dissertation explores the transnational dimensions of the Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927. By including the activities of Syrian migrants in Egypt, Europe and the Americas, this study moves away from state-centric histories of the anti-French rebellion. Though they lived far away from the battlefields of Syria and Lebanon, migrants championed, contested, debated, and imagined the rebellion from all corners of the mahjar (or diaspora). Skeptics and supporters organized petition campaigns, solicited financial aid for rebels and civilians alike, and partook in various meetings and conferences abroad. Syrians abroad also clandestinely coordinated with rebel leaders for the transfer of weapons and funds, as well as offered strategic advice based on the political climates in Paris and Geneva. Moreover, key émigré figures played a significant role in defining the revolt, determining its goals, and formulating its program. By situating the revolt in the broader internationalism of the 1920s, this study brings to life the hitherto neglected role migrants played in bridging the local and global, the national and international. -

Lebanese Christian Nationalism: a Theoretical Analyses of a National Movement

1 Lebanese Christian nationalism: A theoretical analyses of a national movement A Masters Thesis Presented by Penelope Zogheib To the faculty of the department of Political Science at Northeastern University In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Northeastern University Boston, MA December, 2013 2 Lebanese Christian nationalism: A theoretical analyses of a national movement by Penelope Zogheib ABSTRACT OF THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December, 2013 3 ABSTRACT OF THESIS This thesis examines the distinctiveness of Lebanese Christian identity, and the creation of two interconnected narratives pre and during the civil war: the secular that rejects Arab nationalism and embraces the Phoenician origins of the Lebanese, and the marriage of the concepts of dying and fighting for the sacred land and faith. This study portrays the Lebanese Christian national movement as a social movement with a national agenda struggling to disseminate its conception of the identity of a country within very diverse and hostile societal settings. I concentrate on the creation process by the ethnic entrepreneurs and their construction of the self-image of the Lebanese Christian and the perception of the "other" in the Arab world. I study the rhetoric of the Christian intelligentsia through an examination of their writings and speeches before, during and after the civil war, and the evolution of that rhetoric along the periods of peace and war. I look at how the image of “us” vs. -

The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918)

The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) by Melanie Tanielian A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Beshara Doumani Professor Saba Mahmood Professor Margaret L. Anderson Professor Keith D. Watenpaugh Fall 2012 The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) © Copyright 2012, Melanie Tanielian All Rights Reserved Abstract The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) By Melanie Tanielian History University of California, Berkeley Professor Beshara Doumani, Chair World War I, no doubt, was a pivotal event in the history of the Middle East, as it marked the transition from empires to nation states. Taking Beirut and Mount Lebanon as a case study, the dissertation focuses on the experience of Ottoman civilians on the homefront and exposes the paradoxes of the Great War, in its totalizing and transformative nature. Focusing on the causes and symptoms of what locals have coined the ‘war of famine’ as well as on international and local relief efforts, the dissertation demonstrates how wartime privations fragmented the citizenry, turning neighbor against neighbor and brother against brother, and at the same time enabled social and administrative changes that resulted in the consolidation and strengthening of bureaucratic hierarchies and patron-client relationships. This dissertation is a detailed analysis of socio-economic challenges that the war posed for Ottoman subjects, focusing primarily on the distorting effects of food shortages, disease, wartime requisitioning, confiscations and conscriptions on everyday life as well as on the efforts of the local municipality and civil society organizations to provision and care for civilians. -

The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2016 The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905 Manal Kabbani College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kabbani, Manal, "The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626979. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-5ysg-8x13 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Infusion of Stars and Stripes: Sectarianism and National Unity in Little Syria, New York, 1890-1905 Manal Kabbani Springfield, Virginia Bachelors of Arts, College of William & Mary, 2013 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Comparative and Transnational History The College of William and Mary January 2016 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (anal Kabbani . Approved by the Committee, October, 2014 Committee Chair Assistant Professor Ayfer Karakaya-Stump, History The College of William & Mary Associate Professor Hiroshi Kitamura, History The College of William & Mary AssistafvTProfessor Fahad Bishara, History The College of William & Mary ABSTRACT In August of 1905, American newspapers reported that the Greek Orthodox Bishop of the American Antioch, Rafa’el Hawaweeny, asked his Syrian migrant congregation to lay down their lives for him and kill two prominent Maronite newspaper editors in Little Syria, New York. -

Lebanon's Versatile Nationalism

EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2008/13 MEDITERRANEAN PROGRAMME SERIES Lebanon’s Versatile Nationalism Tamirace Fakhoury Muehlbacher EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES MEDITERRANEAN PROGRAMME Lebanon’s Versatile Nationalism TAMIRACE FAKHOURY MUEHLBACHER EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2008/13 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). Requests should be addressed directly to the author(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. The author(s)/editor(s) should inform the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the EUI if the paper will be published elsewhere and also take responsibility for any consequential obligation(s). ISSN 1028-3625 © 2008 Tamirace Fakhoury Muehlbacher Printed in Italy in May 2008 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy http://www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ http://cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), directed by Stefano Bartolini since September 2006, is home to a large post-doctoral programme. Created in 1992, it aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research and to promote work on the major issues facing the process of integration and European society. The Centre hosts major research programmes and projects, and a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration and the expanding membership of the European Union. -

Nicholas Brooke Phd Thesis

THE DOGS THAT DIDN'T BARK: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND NATIONALISM IN SCOTLAND, WALES AND ENGLAND Nicholas Brooke A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2016 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/8079 This item is protected by original copyright The Dogs That Didn't Bark: Political Violence and Nationalism in Scotland, Wales and England Nicholas Brooke This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 30th June 2015 1 Abstract The literature on terrorism and political violence covers in depth the reasons why some national minorities, such as the Irish, Basques and Tamils, have adopted violent methods as a means of achieving their political goals, but the study of why similar groups (such as the Scots and Welsh) remained non-violent, has been largely neglected. In isolation it is difficult to adequately assess the key variables behind why something did not happen, but when compared to a similar violent case, this form of academic exercise can be greatly beneficial. This thesis demonstrates what we can learn from studying ‘negative cases’ - nationalist movements that abstain from political violence - particularly with regards to how the state should respond to minimise the likelihood of violent activity, as well as the interplay of societal factors in the initiation of violent revolt. This is achieved by considering the cases of Wales, England and Scotland, the latter of which recently underwent a referendum on independence from the United Kingdom (accomplished without the use of political violence) and comparing them with the national movement in Ireland, looking at both violent and non-violent manifestations of nationalism in both territories. -

Religion, Peacebuilding, and Social Cohesion in Conflict-Affected Countries

Religion, Peacebuilding, and Social Cohesion in Conflict-affected Countries Research Report Authors Fletcher D. Cox, Catherine R. Orsborn, and Timothy D. Sisk Project Team Contacts Fletcher D. Cox, Research Fellow and Doctoral Candidate Josef Korbel School of International Studies Email: fl[email protected] Catherine R. Orsborn, Research Associate and Doctoral Candidate University of Denver-Iliff School of Theology Joint Doctoral Program Email: [email protected] Timothy D. Sisk, Professor and Associate Dean for Research Josef Korbel School of International Studies Email: [email protected] © Fletcher D. Cox, Catherine R. Orsborn, and Timothy D. Sisk. All rights reserved. This report presents case study findings from a two-year research and policy-dialogue initiative that explores how international peacemakers and development aid providers affect social cohesion in conflict-affected countries. Field research conducted by leading international scholars and global South researchers yields in-depth analyses of social cohesion and related peacebuilding efforts in Guatemala, Kenya, Lebanon, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, and Sri Lanka. The project was coordinated by the Sié Chéou Kang Center for International Security and Diplomacy at the University of Denver from 2012 - 2014, and supported by a generous grant from Henry Luce Foundation’s Initiative on Religion and International Affairs. Religion, Social Cohesion and Peacebuilding in Conflict-affected Countries: Research Report Contents Overview and Summary Findings 1. Introduction 1.1 An Era of Ethno-religious Violence ................................................................................ 2 1.2 Research Question: When do external peacebuilders foster social cohesion? ...................... 2 1.3 About this Project ..................................................................................................... 4 2. Case Study Summary Findings 2.1 Guatemala: Local Social Cohesion versus National Fragmentation ................................... -

Nationalism and Ethnic Politics

This article was downloaded by:[Ingenta Content Distribution - Routledge] On: 27 April 2008 Access Details: [subscription number 791963552] Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Nationalism and Ethnic Politics Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713636289 The political transformation of the Maronites of Lebanon: From dominance to accommodation Simon Haddad a a Notre Dame University, Lebanon Online Publication Date: 01 June 2002 To cite this Article: Haddad, Simon (2002) 'The political transformation of the Maronites of Lebanon: From dominance to accommodation', Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 8:2, 27 - 50 To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/13537110208428660 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13537110208428660 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Green Book Cover Rev5

THE GREEN BUSINESS HANDBOOK Green Actors and Green Marketing DIRECTORY Contact details for companies listed here are in the general directory listing in the last part of this handbook GREEN NGOS FOR BUSINESSES Jozour Loubnan Tree planting campaigns AFDC Tree planting campaigns LibanPack Green packaging design Beeatoona E-cycling all electronic Lebanese Green Building Council equipment Green building certification (ARZ) Cedars for Care Operation Big Blue Association Disposable and biodegradable Seashore cleaning campaigns cutlery TERRE Liban Craft Recycling paper and plastics Recycling paper Recycled notebooks and paper Horsh Ehden Reserve Vamos Todos Eco-tourism activities Eco-tourism activities 133 THE GREEN BUSINESS HANDBOOK Green Actors and Green Marketing CHECKLIST – GREEN MARKETING ❏ Use green material in product packaging and production ❏ Use green methods in product promotion and advertisement ❏ Use online methods to buy and sell products and services ❏ Use online methods to conduct corporate meetings ❏ Brand the product indicating its green attributes (biodegradable, saved trees, recyclable) ❏ Engage the customer in providing feedback on green products and services ❏ Obtain credible certification and make it visible. ❏ Make information readily available about the green initiative. ❏ Provide accurate, understandable information (Use ‘Recyclable Plastic’ instead of ‘Environmentally Friendly’) ❏ Report sustainability to employees, clients, and stakeholders transparently. ❏ Ensure that customer questions and remarks on the product’s -

Here Is Another Accounting Due

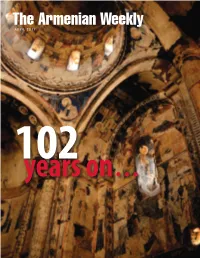

The Armenian Weekly APRIL 2017 102years on . The Armenian Weekly NOTES REPORT 4 Contributors 19 Building Bridges in Western Armenia 5 Editor’s Desk —By Matthew Karanian COMMENTARY ARTS & LITERATURE 7 ‘The Ottoman Lieutenant’: Another Denialist 23 Hudavendigar—By Gaye Ozpinar ‘Water Diviner’— By Vicken Babkenian and Dr. Panayiotis Diamadis RESEARCH REFLECTION 25 Diaspora Focus: Lebanon—By Hagop Toghramadjian 9 ‘Who in this room is familiar with the Armenian OP-ED Genocide?’—By Perry Giuseppe Rizopoulos 33 Before We Talk about Armenian Genocide Reparations, HISTORY There is Another Accounting Due . —By Henry C. Theriault, Ph.D. 14 Honoring Balaban Hoja: A Hero for Armenian Orphans 41 Commemorating an Ongoing Genocide as an Event —By Dr. Meliné Karakashian of the Past . —By Tatul Sonentz-Papazian 43 The Changing Significance of April 24— By Michael G. Mensoian ON THE COVER: Interior of the Church of St. Gregory of Tigran 49 Collective Calls for Justice in the Face of Denial and Honents in Ani (Photo: Rupen Janbazian) Despotism—By Raffi Sarkissian The Armenian Weekly The Armenian Weekly ENGLISH SECTION THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY The opinions expressed in this April 2017 Editor: Rupen Janbazian (ISSN 0004-2374) newspaper, other than in the editorial column, do not Proofreader: Nayiri Arzoumanian is published weekly by the Hairenik Association, Inc., necessarily reflect the views of Art Director: Gina Poirier 80 Bigelow Ave, THE ARMENIAN WEEKLY. Watertown, MA 02472. ARMENIAN SECTION Manager: Armen Khachatourian Sales Manager: Zovig Kojanian USPS identification statement Editor: Zaven Torikian Periodical postage paid in 546-180 TEL: 617-926-3974 Proofreader: Garbis Zerdelian Boston, MA and additional FAX: 617-926-1750 Armenian mailing offices. -

The Crisis in Lebanon: a Test of Consociational Theory

THE CRISIS IN LEBANON: A TEST OF CONSOCIATIONAL THEORY BY ROBERT G. CHALOUHI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1978 Copyright 1978 by Robert G. Chalouhi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my thanks to the members of my committee, especially to my adviser, Dr. Keith Legg, to whom I am deeply indebted for his invaluable assistance and guidance. This work is dedicated to my parents, brother, sister and families for continued encouragement and support and great confidence in me; to my parents-in-law for their kindness and concern; and especially to my wife Janie for her patient and skillful typing of this manuscript and for her much- needed energy and enthusiasm. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii ABSTRACT ix CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 1 Applicability of the Model 5 Problems of System Change 8 Assumption of Subcultural Isolation and Uniformity 11 The Consociational Model Applied to Lebanon 12 Notes 22 CHAPTER II THE BEGINNINGS OF CONSOCIATIONALISM: LEBANON IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE. 25 The Phoenicians 27 The Birth of Islam 29 The Crusaders 31 The Ottoman Empire 33 Bashir II and the Role of External Powers 38 The Qaim Maqamiya 41 The Mutasarrif iyah: Confessional Representation Institutionalized. 4 6 The French Mandate, 1918-1943: The Consolidation of Consociational Principles 52 Notes 63 CHAPTER III: THE OPERATION OF THE LEBANESE POLITICAL SYSTEM 72 Confessionalism and Proportionality: Nominal Actors and Formal Rules . 72 The National Pact 79 The Formal Institutions 82 Political Clientelism: "Real" Actors and Informal Rules The Politics of Preferment and Patronage 92 Notes 95 CHAPTER IV: CONSOCIATIONALISM PUT TO THE TEST: LEBANON IN THE FIFTIES AND SIXTIES.