Seeley, Edgar Stanley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Harcourt Adams – Frankie Munro

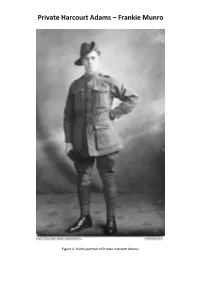

Private Harcourt Adams – Frankie Munro Figure 1: Studio portrait of Private Harcourt Adams. These are the stories of two brave Tasmanian men. The first of which, my friend’s ancestor, a sailor from Swansea, killed at Pozières in 1916. The second, a lost relative of mine that I discovered through the Frank MacDonald Memorial Prize, also killed at Pozières in 1916. Harcourt (Duke) Adams was born in Swansea on the 8 August 1890 to parents Frederick and Alice Adams. Prior to his enlistment, he was a fireman on board a steamship owned by the Mt. Lyell Co. When his ship was in port in Hobart, he lived with his mother and younger sister, Ivy. His four other sisters, Minnie, Violet, Lilly and Ruby had married and lived elsewhere, and his father tragically passed away several years before the war, so Harcourt was providing the only income for them when he enlisted. Harcourt enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on the 11 June 1915, aged 24. He was given the service number 2496 and assigned to the 15th Battalion, 7th Reinforcements. Figure 2: 15th Battalion AIF colour patch. On the 17 July 1915, Harcourt embarked from Melbourne on board the HMAT Orsova A67. Several photographs were taken of the ship as it left Port Melbourne, the soldiers can be seen lining the deck, bidding farewell to the crowd, some even climbed the rigging. There is the possibility that one of those men was Harcourt. Figure 3: HMAT Orsova A67 leaving Port Melbourne, 17.07.1915. Figure 4: A closeup shot of the Orsova showing the Australian soldiers on board, 17.07.1915. -

We Remember Those Members of the Lloyd's Community Who Lost Their

Surname First names Rank We remember those members of the Lloyd’s community who lost their lives in the First World War 1 We remember those who lost their lives in the First World War SurnameIntroduction Today, as we do each year, Lloyd’s is holding a But this book is the story of the Lloyd’s men who fought. Firstby John names Nelson, Remembrance Ceremony in the Underwriting Room, Many joined the County of London Regiment, either the ChairmanRank of Lloyd’s with many thousands of people attending. 5th Battalion (known as the London Rifle Brigade) or the 14th Battalion (known as the London Scottish). By June This book, brilliantly researched by John Hamblin is 1916, when compulsory military service was introduced, another act of remembrance. It is the story of the Lloyd’s 2485 men from Lloyd’s had undertaken military service. men who did not return from the First World War. Tragically, many did not return. This book honours those 214 men. Nine men from Lloyd’s fell in the first day of Like every organisation in Britain, Lloyd’s was deeply affected the battle of the Somme. The list of those who were by World War One. The market’s strong connections with killed contains members of the famous family firms that the Territorial Army led to hundreds of underwriters, dominated Lloyd’s at the outbreak of war – Willis, Poland, brokers, members and staff being mobilised within weeks Tyser, Walsham. of war being declared on 4 August 1914. Many of those who could not take part in actual combat also relinquished their This book is a labour of love by John Hamblin who is well business duties in order to serve the country in other ways. -

Publicité Du 15/07/2019 Au 16/09/2019

PRÉFÈTE DE LA SOMME Direction Départementale des Territoires et de la Mer Service Economie Agricole Bureau structures et installations PUBLICITÉ relative à une demande d'autorisation d'exploiter au titre du CONTRÔLE DES STRUCTURES des EXPLOITATIONS AGRICOLES conformément aux articles R331-4 et D331-4-1 du code rural et de la pêche maritime Liste des parcelles objet de demande d'autorisation d'exploiter n° 8019357 Date d'enregistrement de la demande : 28/06/2019 Demandeur : DOLIGEZ Estelle Date limite de dépôt des demandes d'autorisation d'exploiter en concurrence avec ce dossier est fixée au : 16/09/2019 Toute demande déposée après cette date ne pourra être mis en concurrence avec la présente demande. COMMUNES Références cadastrales Superficie en ha Nom prénom des propriétaires CANCHY B 569 0,4384 DOLIGEZ Sylvain CANCHY B 513 0,041 DOLIGEZ Sylvain CANCHY B 127 0,0467 DOLIGEZ Sylvain Les demandes d’autorisation d’exploiter doivent être déposées auprès de la DDTM du département de la Somme. Le formulaire de demande d’autorisation d’exploiter est téléchargeable sur le site internet de la préfecture de la Somme ou celui de la Préfecture de région. dossier n°8019357 PRÉFÈTE DE LA SOMME Direction Départementale des Territoires et de la Mer Service Economie Agricole Bureau structures et installations PUBLICITÉ relative à une demande d'autorisation d'exploiter au titre du CONTRÔLE DES STRUCTURES des EXPLOITATIONS AGRICOLES conformément aux articles R331-4 et D331-4-1 du code rural et de la pêche maritime Liste des parcelles objet de demande d'autorisation d'exploiter n° 8019360 Date d'enregistrement de la demande : 02/07/2019 Demandeur : SCEA KETELS Date limite de dépôt des demandes d'autorisation d'exploiter en concurrence avec ce dossier est fixée au : 16/09/2019 Toute demande déposée après cette date ne pourra être mis en concurrence avec la présente demande. -

Vainqueurs De La Coupe De France Excellence

VAINQUEURS DE LA COUPE DE FRANCE EXCELLENCE Année Nom de l’équipe Nom du foncier 1991 DERNANCOURT BERTOUX Eric 1992 SENLIS LE SEC MAISSE Michel 1993 HERISSART BERTOUX Eric 1994 FRANVILLERS DEBART Stéphane 1995 SENLIS LE SEC MAISSE Michel 1996 LOUVENCOURT TILLOLOY Philippe 1997 FRANVILLERS BERTOUX Eric 1998 WARLOY BAILLON BELISON Manuel 1999 FRANVILLERS DEBROY Ludovic 2000 LOUVENCOURT PECOURT Olivier 2001 WARLOY BAILLON BELISON Manuel 2002 FRANVILLERS BERTOUX Eric 2003 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste 2004 BEAUQUESNE DEBART Stéphane 2005 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste 2006 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste 2007 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste 2008 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste 2009 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste 2010 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste 2011 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste 2012 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste 2013 BEAUQUESNE DERNY Anthony 2014 BEAUQUESNE DERNY Anthony 2015 BEAUQUESNE DERNY Anthony 2016 LOUVENCOURT PECOUL Jean Baptiste VAINQUEURS DE LA COUPE DE FRANCE 1ère A Année Nom de l'équipe Nom du foncier 1991 AMIENS LEQUETTE Gérard 1992 LUCHEUX CLERGE Fabrice 1993 WARLOY BAILLON SAVEYN Franck 1994 RAINCHEVAL PATAUT Eric 1995 TERRAMESNIL SAGUEZ Jocelyn 1996 AMIENS LEQUETTE Gérard 1997 AMIENS ATTELEYN Pascal 1998 et 1999 TOUTENCOURT CHOQUET Bruno 2000 TOUTENCOURT BRIAULT Jérôme 2001 BEAUQUESNE ANDRIEU David 2002 BEAUQUESNE DERNY Cédric 2003 SENLIS LE SEC TILLOLOY Vincent 2004 SENLIS LE SEC POQUET Gilles 2005 FRANVILLERS BELLOTTO David 2006 RAINNEVILLE MORDACQUE Jonathan 2007 SENLIS LE SEC VITTE Benjamin 2008 HERISSART -

Major Swindell's World War 1 Diary

This article contains extracts from the war diary of my Grandfather, Major Swindell. He was a Pioneer in the 2nd Battalion Manchester Regiment. Having joined the colours in 1906, he served right through the war, from being one of the Old Contemptibles, all the way to the armistice. He ended the war as Battalion Pioneer Sgt. The diary was written in two separate volumes – one is a Letts diary for 1915, covering the period 5th August 1914 to 31st December 1916 and the other is a notebook which covers the period 1st January 1916 to 3rd September 1918. The diary ends two months before the armistice. I don’t know whether he ended there or if he started a missing third volume. The diary covers most of the major battles of WW1 – starting with the Retreat from Mons (including Le Cateau), the Marne/Aisne, First Ypres, Second Ypres, The Somme/Ancre, Messines and the 1918 offensives. The reader may be puzzled about my grandfather’s name, Major. The story goes that this unusual name came about from a short-lived tradition in his family of naming the boys after army ranks. Major was the last one, as after he was born, all the women in the family got together and put a stop to it. My father read parts of the diary over the years, but he was put off reading the whole thing, as the handwriting can be quite difficult to decipher. I decided to attempt to transcribe the diary for the benefit of both my father (who died shortly after I finished) and future generations. -

Minimes Cadet

Minimes 3ème journée 9-déc. Éliminatoire 1: Talmas 10 Beauquesne 3 Éliminatoire 2: Senlis le Sec 7 Beauval 10 5 et 6 : Beauquesne 2 Senlis le Sec 10 1ère 1/2 finale: Talmas 10 Beauval 8 2ème 1/2 finale: Forceville 10 Raincheval 6 3 et 4 : Beauval 10 Raincheval 7 Finale : Talmas 10 Forceville 4 Classement: 3ème journée 9-déc. Talmas 21 points Beauval 12 points Forceville 11 points Raincheval 9 points Senlis le Sec 8 points Beauquesne 5 points 4ème journée 9-déc Éliminatoire 1: Beauval 10 Forceville 7 Raincheval = forfait 5 et 6 : non disputé 1ère 1/2 finale: Beauval 4 Talmas 10 2ème 1/2 finale: Senlis le Sec 10 Beauquesne 3 3 et 4 : Beauval 10 Beauquesne 4 Finale : Talmas 10 Senlis le Sec 8 Classement: 4ème journée 23-déc. Talmas 28 points Beauval 16 points Forceville 13 points Senlis le Sec 13 points Raincheval 9 points Beauquesne 7 points Cadet 3ème journée 1ère 1/2 finale: Beauval 1 Terramesnil 10 2ème 1/2 finale: Raincheval 10 Ribemont sur Ancre 0 3 et 4 : Beauval 8 Ribemont sur Ancre 10 Finale : Terramesnil 8 Raincheval 10 Classement 3ème journée 2-dé Raincheval 21 points Terramesnil 14 points Beauval 11 points Ribemont sur Ancre 8 points 4ème journée 1ère 1/2 finale: Raincheval 10 Beauval 0 2ème 1/2 finale: Terramesnil 10 Ribemont sur Ancre 2 3 et 4 : Beauval 5 Ribemont sur Ancre 10 Finale : Raincheval 10 Terramesnil 6 Classement: 4ème journée 16-déc. Raincheval 28 points Terramesnil 19 points Beauval 13 points Ribemont sur Ancre 12 points 2eme Poule 1 2ème journée 1ère 1/2 finale: Raincheval AB 3 Toutencourt 10 2ème 1/2 finale: Beauval LLG 10 Lucheux 3 3 et 4 : Raincheval AB 10 Lucheux 8 Finale : Toutencourt 5 Beauval LLG 10 Classement 2ème journée 1-déc. -

Albert Et Le Pays Du Coquelicot, Terre D’Innovation Industrielle Dossier Central Pages 9 À 12

Mars 2012 - N° 91 Albert et le Pays du Coquelicot, terre d’innovation industrielle Dossier central pages 9 à 12 Le budget 2012 page 5 hier . JSP : le retour ! page 15 . aujourd’hui . © ASCODERO Le relais d’assistantes maternelles page 16 . et demain “ Ne demande pas à ton pays ce qu’il peut faire pour toi, demande-toi ce que tu peux faire pour lui ” J.F. KENNEDY ARS SOMMAIRE M 2012 2 n°91 - mars 2012 SOMMAIRE MARS 2012 Édito 03 Mairie pratique 04 Budget 2012 05 Tourisme/culture 06 Madame, Mademoiselle, Monsieur, Vivre ensemble 07 Dossier 9 Hier, en 1835, avec les premières machines-outils de précision, aujourd’hui avec le développement du composite, demain avec les projets à haute valeur ajoutée Economie/emploi 13 technologique INDUSTRILAB et CADEMCE… Albert et le Pays du Coquelicot n’ont Portraits d’Albertins 14 jamais cessé d’être une terre d’innovation industrielle. Sport/Activités 15 Social/Santé 16 Alors que les travaux d’aménagement de la nouvelle ZAC du Coquelicot sont terminés et que les premiers travaux d’implantation d’entreprises (Laroche Industrie, Environnement 17 Figeac Aero Picardie, Blondel Aérologistique, Segula, Village PMI ...) vont débuter, Loisirs 18 le dossier central de ce numéro de printemps d’ “Albert en Direct” vous fait revivre cette quête incessante de l’excellence technologique et industrielle qui fait battre le cœur économique de notre territoire depuis près de deux siècles. Baroux, Toulet, Pifre, Liné, Hurtu, Potez…mais aussi composite, CAO, KERADOUCE, UGV (Usinage à Grande Vitesse), réalité virtuelle... sont autant de noms de pionniers, de techniques ou de procédés qui ont fait, qui font, et qui feront la vitalité Albert en Direct de l’industrie albertine. -

Beaumont Hamel - SE01-2 Mémorial Du Commonwealth « 29 Th Division (Newfoundland) Memorial »

Association « Paysages et Sites de mémoire de la Grande Guerre » SECTEUR K - LA VALLÉE DE L’ANCRE SE01 SE02 SE03 SE04 Description générale du secteur mémoriel Le secteur mémorial de la « Vallée de l'Ancre » se situe sur le plateau de l’Amiénois, sur les rives est et ouest de la rivière Ancre – un affluent de la Somme. Son organisation spatiale d’openfield en fait un paysage agraire ouvert, ponctué de villages, hameaux et bois. Le « saillant de Leipzig », sur les hauteurs, culmine à plus de 140m à l’est et constitue une véritable forteresse naturelle, dominant la vallée de l’Ancre. Au plan géologique, la vallée présente un limon argilo-sableux, tandis que le sol du plateau est constitué tant d’argile que de limon. Ces caractéristiques géologiques ont été utilisées pendant le conflit et ont eu un impact sur l’offensive. Le secteur mémoriel « Vallée de l'Ancre » regroupe quatre éléments constitutifs. Son homogénéité, tant chronologique qu’environnementale, architecturale et spatiale, en fait un lieu mémoriel unique, doté d’un maillage très dense de mémoriaux, cimetières et paysages marqués par le conflit. Chacun se distingue par une identité individuelle forte et complémentaire. C’est un territoire rural totalement « sacralisé », pour lequel la dimension funéraire de la Première Guerre mondiale constitue la première caractéristique : outre les stèles des combattants inhumés dans les cimetières, c’est surtout le « missing » ou « disparu » en anglais qui se trouve au cœur du discours architectural. En parallèle, la proximité et le principe de co-visibilité entre chaque élément constitutif contribuent à définir l’identité symbolique, esthétique et mémorielle unique qui caractérise cet espace, né de la bataille de la Sommeen 1916 (1 er juillet-18 novembre). -

Enquete Publique Rapport Et

ENQUETE PUBLIQUE du 2 novembre au 2 décembre 2016 PROJET DE PLAN DE SERVITUDES AERONAUTIQUES DE DEGAGEMENT AERODROME d’ALBERT - BRAY RAPPORT ET CONCLUSIONS Guy MONFRIER Commissaire - Enquêteur Enquête Publique n° E 16000170/80 : Plan de servitudes aéronautiques de 1. dégagement de l’aérodrome Albert – Bray. 2 Enquête Publique n° E 16000170/80 : Plan de servitudes aéronautiques de dégagement de l’aérodrome Albert – Bray. SOMMAIRE RAPPORT I GENERALITES : 6 I – 1 : LE CADRE JURIDIQUE DU PROJET . 7 I - 2 : L’HISTORIQUE DE L’AERODROME . 7 I – 3 : LA SITUATION ACTUELLE . .. 9 II LES PREALABLES A L’ENQUÊTE PUBLIQUE : 10 II – 1 : LA COMPOSITION DU DOSSIER . 11 II – 2 : LA CONFERENCE ENTRE SERVICES . 11 II – 3 : LA PREPARATION DE L’ENQUÊTE PUBLIQUE . 12 III LE DEROULEMENT DE L’ENQUÊTE 14 III – 1 : L’INFORMATION DU PUBLIC . 14 III – 2 : LES PERMANENCES EN MAIRIES . 15 III – 3 : LA CLOTURE DE L’ENQUÊTE PUBLIQUE. 16 ANNEXES AU RAPPORT LISTE DES ANNEXES . 18 . Enquête Publique n° E 16000170/80 : Plan de servitudes aéronautiques de 3. dégagement de l’aérodrome Albert – Bray. CONCLUSIONS ET AVIS CONCLUSIONS . 28 AVIS . 30 4 Enquête Publique n° E 16000170/80 : Plan de servitudes aéronautiques de dégagement de l’aérodrome Albert – Bray. RAPPORT D’ENQUÊTE PUBLIQUE Enquête Publique n° E 16000170/80 : Plan de servitudes aéronautiques de 5. dégagement de l’aérodrome Albert – Bray. I GENERALITES : Par lettre en date du 2 octobre 2015, Madame la ministre de l’écologie, du développement durable et de l’énergie – Direction Générale de l’Aviation Civile – Direction des transports aériens – identifiait la nécessité d’établir un plan de servitudes aéronautiques de dégagement de l’aérodrome d’Albert-Bray. -

Muche » De Bouzincourt (Somme)

Observations et avis du brgm concernant deux éboulements dans la « muche » de Bouzincourt (Somme) Compte rendu de la visite du 30 janvier 2008 Rapport final BRGM/RP-56150-FR février 2008 Observations et avis du brgm concernant deux éboulements dans la « muche » de Bouzincourt (Somme) Compte rendu de la visite du 30 janvier 2008 Rapport final BRGM/RP-56150-FR février 2008 Étude réalisée dans le cadre des projets de Service public du BRGM 08PIRA25 P. Chrétien Vérificateur : Approbateur : Nom : C. Mathon Nom : J.P. Lepretre Date : le 18/02/2008 Date : le 19/02/2008 En l’absence de signature, notamment pour les rapports diffusés en version numérique, l’original signé est disponible aux Archives du BRGM. Le système de management de la qualité du BRGM est certifié AFAQ ISO 9001:2000. I M 003 SIMP - AVRIL. 05 Mots clés : En bibliographie, ce rapport sera cité de la façon suivante : P. Chrétien (2008) – Observations et avis du brgm concernant deux éboulements dans la « muche » de Bouzincourt (Somme). Rapport final. Compte rendu de la visite du 30 janvier 2008. BRGM/RP-56150-FR, 36 pages, 11 illustrations, 2 annexes. © BRGM, 2008, ce document ne peut être reproduit en totalité ou en partie sans l’autorisation expresse du BRGM. Muche de Bouzincourt (80) – Observations et avis du brgm concernant 2 éboulements – Janvier 2008 Synthèse Deux éboulements de terrain ont été constatés en janvier 2008 dans la muche de Bouzincourt (Somme) par les services de la mairie de la commune. Ils ont été portés à la connaissance du Bureau Interministériel de Défense et Sécurité Civiles (BIRDSC) de la Préfecture de la Somme le 28 janvier 2008. -

Communauté De Communes Du Pays Du Coquelicot 20/06/2019 DDTM De

SCoT du Grand Amiénois - Porter à connaissance Liste des servitudes d'utilité publique 1 / 44 Commune Code Insee Intulé de la servitude Type Caractérisques Acte générateur Gesonnaire ACHEUX-EN- 80003 Servitudes résultant de l'instauration de périmètres de AS1 Autorisation d'utilisation de l'eau prélevée dans le milieu naturel en vue de la Arrêté Préfectoral du 30 Agence régionale de santé AMIENOIS protection des eaux potables et minérales. consommation humaine. décembre 2004 Service Santé Environnementale de la Somme Déclaration d'utilité publique des travaux de dérivation des eaux et d'établissement des Direction de la Sécurité Sanitaire et de la Santé périmètres de protection du captage d'indice national 00355X008 situé sur le territoire Environnementale d'Acheux en Amiènois. 52 rue Daire CS 73706 80037 AMIENS cedex 1 ACHEUX-EN- 80003 Servitudes résultant de l'instauration de périmètres de AS1 Captage de Léalvillers Arrêté Préfectoral du Agence régionale de santé AMIENOIS protection des eaux potables et minérales. 12/01/2006 Service Santé Environnementale de la Somme Direction de la Sécurité Sanitaire et de la Santé Environnementale 52 rue Daire CS 73706 80037 AMIENS cedex 1 ACHEUX-EN- 80003 Servitudes relatives à l'établissement des canalisations I4 Ligne Haute Tension 2 x 400 KV ARGOEUVES _ CHEVALET 1 et 2 (ex. ligne RTE DIES - Direction Développement Ingénierie AMIENOIS électriques. Argoeuves - Avelin). Centre Développement Ingénierie Lille Pour toute précision complémentaire se rapprocher du service responsable. Service Concertation Environnement Tiers Animateur Les travaux à proximité de ces ouvrages sont réglementés par le décret 65-48 du Régional SIG Lille 08/01/1965 et la circulaire 70-21 du 21/12/1970. -

Secrétariats Et Directions Annuaire Des Du Pays Du Coquelicot De Mairie

Annuaire des secrétariats et directions de mairie du Pays du Coquelicot MAJ MAJ février 2019 Recherche par commune : Recherche par secrétaire : Acheux-en-Amiénois Grandcourt Albert Harponville BATTY Denis Arquèves Hédauville BAYARD Hervé Auchonvillers Hérissart BLANCHARD Laurence Authie Irles BORMANS Patricia Authuille La Neuville-lès-Bray BORMANS Régis FIEVET Bertrand Aveluy Laviéville BOULANGER Christine GLIN Vanessa Bayencourt Léalvillers BOULARD Ludivine MARY Marina Bazentin Louvencourt BRIET Céline GRAUX Marlène GRAUX Valérie Beaucourt-sur-l'Ancre Mailly-Maillet CARDON Annie GRIGNY Carole Beaumont-Hamel Maricourt CAUUET Aurore GOUBET Odile Bécordel-Bécourt Marieux CHEVALIER Diane CHOQUET Mathilde GUERLE Sébastien Bertrancourt Méaulte CORBIER Lucile LACAILLE Christine Bouzincourt Mesnil-Martinsart CRAMPON Emmanuelle LAMBERT Maryline Bray-sur-Somme Millencourt CROCHET Evelyne LANDO Annie Buire-sur-Ancre Miraumont DARRAS Sylvie LEGRAND Brigitte Bus-lès-Artois Montauban-de- DELETRE Sabine LEVRIEN Elisabeth Picardie Cappy DERVAUX Florence LORIOT Fabienne Morlancourt Carnoy-Mametz DEVOGELAERE Fabienne MAJOT Laetitia Ovillers-La-Boisselle Chuignolles DRIENCOURT Christiane MEHAYE Catherine Puchevillers Coigneux DUFOUR Odile MOREL Annette Pys Colincamps DUMONT Aurore NIBART Isabelle Pozières Contalmaison ELOY Eliane OMIEL Marie-Christine Raincheval PICAVET Corinne Courcelette FARSI Fatima Saint-Léger-lès-Authie PILARSKI Mélanie Courcelles-au-Bois FELIX Delphine Senlis-le-Sec SERAFFIN Julien Curlu Suzanne SIMEK Mélody Dernancourt WALLET Marie