Orchestra Sex Disparity: Experimental Evidence from Audience Members

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz

CoNSERVATORY oF Music presents The Violin Studio of Sergiu Schwartz SPOTLIGHT ON YOUNG VIOLIN VIRTUOSI with Tao Lin, piano Saturday, April 3, 2004 7:30p.m. Amamick-Goldstein Concert Hall de Hoernle International Center Program Polonaise No. 1 in D Major ..................................................... Henryk Wieniawski Gabrielle Fink, junior (United States) (1835 - 1880) Tambourin Chino is ...................................................................... Fritz Kreisler Anne Chicheportiche, professional studies (France) (1875- 1962) La Campanella ............................................................................ Niccolo Paganini Andrei Bacu, senior (Romania) (1782-1840) (edited Fritz Kreisler) Romanza Andaluza ....... .. ............... .. ......................................... Pablo de Sarasate Marcoantonio Real-d' Arbelles, sophomore (United States) (1844-1908) 1 Dance of the Goblins .................................................................... Antonio Bazzini Marta Murvai, senior (Romania) (1818- 1897) Caprice Viennois ... .... ........................................................................ Fritz Kreisler Danut Muresan, senior (Romania) (1875- 1962) Finale from Violin Concerto No. 1 in g minor, Op. 26 ......................... Max Bruch Gareth Johnson, sophomore (United States) (1838- 1920) INTERMISSION 1Ko<F11m'1-za from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor .................... Henryk Wieniawski ten a Ilieva, freshman (Bulgaria) (1835- 1880) llegro a Ia Zingara from Violin Concerto No. 2 in d minor -

PROGRAM NOTES Wolfgang Mozart Clarinet Concerto in a Major, K

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Clarinet Concerto in A Major, K. 622 Mozart composed this concerto between the end of September and mid-November 1791, and it apparently was performed in Vienna shortly afterwards. The orchestra consists of two flutes, two bassoons, two horns, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-nine minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first performance of Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto was given at the Ravinia Festival on July 25, 1957, with Reginald Kell as soloist and Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra’s first subscription concert performance was given at Orchestra Hall on May 2, 1963, with Clark Brody as soloist and Walter Hendl conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on October 11 and 12, 1991, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Georg Solti conducting. The Orchestra most recently performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival on July 15, 2001, with Larry Combs as soloist and Sir Andrew Davis conducting. This concerto is the last important work Mozart finished before his death. He recorded it in his personal catalog without a date, right after The Magic Flute and La clemenza di Tito. The only later entry is the little Masonic Cantata, dated November 15, 1791. The Requiem, as we know, didn’t make it into the list. For decades the history of the Requiem was full of ambiguity, while that of the Clarinet Concerto seemed quite clear. But in recent years, as we learned more about the unfinished Requiem, questions about the concerto began to emerge. -

June WTTW & WFMT Member Magazine

Air Check Dear Member, The Guide As we approach the end of another busy fiscal year, I would like to take this opportunity to express my The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT heartfelt thanks to all of you, our loyal members of WTTW and WFMT, for making possible all of the quality Renée Crown Public Media Center content we produce and present, across all of our media platforms. If you happen to get an email, letter, 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue or phone call with our fiscal year end appeal, I’ll hope you’ll consider supporting this special initiative at Chicago, Illinois 60625 a very important time. Your continuing support is much appreciated. Main Switchboard This month on WTTW11 and wttw.com, you will find much that will inspire, (773) 583-5000 entertain, and educate. In case you missed our live stream on May 20, you Member and Viewer Services can watch as ten of the area’s most outstanding high school educators (and (773) 509-1111 x 6 one school principal) receive this year’s Golden Apple Awards for Excellence WFMT Radio Networks (773) 279-2000 in Teaching. Enjoy a wide variety of great music content, including a Great Chicago Production Center Performances tribute to folk legend Joan Baez for her 75th birthday; a fond (773) 583-5000 look back at The Kingston Trio with the current members of the group; a 1990 concert from the four icons who make up the country supergroup The Websites wttw.com Highwaymen; a rousing and nostalgic show by local Chicago bands of the wfmt.com 1960s and ’70s, Cornerstones of Rock, taped at WTTW’s Grainger Studio; and a unique and fun performance by The Piano Guys at Red Rocks: A Soundstage President & CEO Special Event. -

The Publication History of Spohr's Clarinet Concertos

THE PUBLICATION HISTORY OF SPOHR'S CLARINET CONCERTOS by Keith Warsop N DISCUSSING the editions used for the recording by French clarinettist paul Meyer of Spohr's four concertos for the instrument on the Alpha label (released as a two-CD set, ALPHA 605, with the orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne), reviewers in the November 2012 issues of the Gramophone and,Internotional Record Review magazines came to some slightly misleading conclusions about this subject so that it has become important to clarify matters. Carl Rosman, writing in 1RR, ,authentic, said: "Meyer has also taken steps towards a more text fbr these concertos. While the clarinet works of Mozart, Brahms and Weber have seen various Urtext editions over the years, Spohr's concertos circulate only in piano reductions from the late nineteenth century ... Meyer has prepared his own editions from the best available sources (the manuscripts of all but No.4 have been lost but there are contemporary manuscript copies of the others held at the Louis Spohr Society in Kassel); this has certainly giu., him lreater freedom in the area of articulation, and also allowed him to adopt some more-flowing temios than the late nineteenth-century editions specify.', In the Gramophone, Nalen Anthoni stated: "Hermstedt demanded exclusive rights and, presumably, kept the autographs. Only that of No.4 was found, in 1960. The other works have been put together from manuscript copies. Paul Meyer seems largely attuned to the solo parts edited by stanley Drucker, the one-time principal ciarinettist of the New york philharmonic. Michael Collins [on the Hyperion label] is of similar mind, though both musicians add their own individual touches phrasing to and articulation. -

Henryk Szeryng – Weltbürger Und Weltklasse-Geiger (3)

SWR2 Musikstunde Henryk Szeryng – Weltbürger und Weltklasse-Geiger (3) Von Jörg Lengersdorf Sendung vom: 18. August 2021 (Erstsendung 19. September 2018) Redaktion: Dr. Ulla Zierau Produktion: SWR 2018 SWR2 können Sie auch im SWR2 Webradio unter www.SWR2.de und auf Mobilgeräten in der SWR2 App hören – oder als Podcast nachhören: Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Die SWR2 App für Android und iOS Hören Sie das SWR2 Programm, wann und wo Sie wollen. Jederzeit live oder zeitversetzt, online oder offline. Alle Sendung stehen mindestens sieben Tage lang zum Nachhören bereit. Nutzen Sie die neuen Funktionen der SWR2 App: abonnieren, offline hören, stöbern, meistgehört, Themenbereiche, Empfehlungen, Entdeckungen … Kostenlos herunterladen: www.swr2.de/app Die Jugend des Geigers Henryk Szeryng ist vorbei, das Studium fast beendet. Eine Weltkarriere scheint auf ihn zu warten. Doch dann sucht der Krieg Europa heim, alles kommt anders… Im Juli 1937 hat der 18jährige Henryk Szeryng gerade einmal 8 Monate in Paris studiert, als er sein Studium am Konservatorium beim Abschlusskonzert mit dem Prestigeträchtigen und begehrten ersten Preis der Kohorte abschließt. Neben Szeryng erhält der ebenfalls bald zur Weltelite gehörende Geiger Yfrah Neaman diese Auszeichnung. Der später legendäre Solist und langjährige Star-Konzertmeister der Berliner Philharmoniker, Michel Schwalbé, bekommt dagegen nur den zweiten Preis. Ein Detail am Rande, das immerhin illustriert, was für ein Niveau die Pariser Professoren in dieser Prüfungsphase 1937 serviert bekommen. In einigen biografischen Abrissen (ausführliche Biografien gibt es noch nicht) liest man nun, Szeryngs Eltern hätten ihm zum Pariser Abschluss eine wertvolle Geige das Cremoneser Meisters Andrea Guarneri geschenkt. -

Radio 3 Listings for 28 December 2019 – 3 January 2020 Page 1 of 16

Radio 3 Listings for 28 December 2019 – 3 January 2020 Page 1 of 16 SATURDAY 28 DECEMBER 2019 (conductor) BBC National Orchestra of Wales Jac van Steen (conductor) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m000cpsr) 05:01 AM BIS BIS2408 (Hybrid SACD) - Released 3rd January 2020 Regensburger Domspatzen at Tage Alter Musik Judith Weir (1954-) String quartet Ravel: Jeux de Miroirs Leopold Mozart shows himself to be a serious composer at the Silesian Quartet Javier Perianes (piano) height of his powers with his Symphony in G and Missa Orchestre de Paris Solemnis. They are performed at the Tage Alter Musik festival 05:13 AM Josep Pons (conductor) in Regensburg, Germany, by the Regensburger Domspatzen and Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Harmonia Mundi HMM902326 the Hofkapelle Munich. Catriona Young presents. 4 Impromptus for piano, D 899 (No 4 in A flat) http://www.harmoniamundi.com/#!/albums/2571 Arthur Schnabel (piano) 01:01 AM 9.30am Building a Library Leopold Mozart (1719-1787) 05:21 AM Symphony in G 'Neue Lambacher', for strings Johann Philipp Kirnberger (1721-1783) Laura Tunbridge discusses a wide range of approaches to Hofkapelle Munchen, Rudiger Lotter (conductor) Cantata, 'An den Flussen Babylons' Schumann's searing Heine cycle and recommends the key Johannes Happel (bass), Balthasar-Neumann-Chor, Balthasar- recording to keep for posterity. 01:18 AM Neumann-Ensemble, Detlef Bratschke (conductor) Leopold Mozart (1719-1787) 10.20am New Releases Missa Solemnis in C 05:33 AM Katja Stuber (soprano), Dorothee Rabsch (contralto), Robert Joaquín Turina (1882-1949) -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

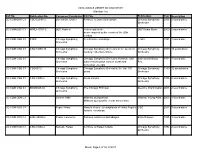

CSOA LEAGUE LIBRARY CD COLLECTION Member List Music

CSOA LEAGUE LIBRARY CD COLLECTION Member List Call No. Publication No. Composer/Conductor CD Title Publication Year Description CD COM BAR C3 CSO-CD-06-2 Barenboim, Daniel A tribute to Daniel Barenboim Chicago Symphony 2006 2 sound discs. Orchestra CD COM BBC C3 WMEF-0051-2 BBC Radio 4. This sceptred isle BBC Radio Music 2000 2 sound discs music inspired by the events of the 20th century. CD COM CSO C3 830IP Chicago Symphony Celebration Fantastique Teldec 1997 1 sound disc. Orchestra CD COM CSO C3 CSO CD00-10 Chicago Symphony Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the twentieth Chicago Symphony 2000 10 audio discs. Orchestra century: collector's choice Orchestra CD COM CSO C3 Chicago Symphony Chicago Symphony Orchestra trombone and Educational Brass 1971 1 sound disc. Orchestra tuba sections plays concert works and Rec. orchestral excerpts CD COM CSO C3 CSO90/12 Chicago Symphony Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the first 100 Chicago Symphony 1990 12 sound discs. Orchestra years Orchestra CD COM CSO C3 CSO CD95-2 Chicago Symphony Great soloists Chicago Symphony 1995 2 sound discs. Orchestra Orchestra CD COM CSO C3 B0000025-02 Chicago Symphony The Chicago Principal Deutche Grammopon 2003 2 sound discs. Orchestra CD COM DEN C3 Dennis, Allan Midwest young artists Midwest Young Artist 2003 1 sound disc Midwest young artitst : tenth anniversary CD COM FOG C3 Fogel, Henry Henry's choice : a compilation of Henry Fogel's CSO 2003 3 sound discs favorite recordings. CD COM FOS C3 2292-45860-2 Foster, Lawrence Famous romances and adagios Erato Disques 1985 1 sound disc. -

Prominent Schools of Clarinet Sound (National Styles)

Prominent Schools of Clarinet Sound (National Styles) German School (Oehler system, up to 27 keys) Description: dark, compact, well in tune but difficult to play very softly Players: Karl Leister, Sabine Meyer French School (Boehm system, 16 or 17 keys) Description: clear, bright/too bright, large dynamic range Players: Anthony Gigliotti, Phillippe Cuper Italian School (Boehm system) Description: voice-like quality Opera tradition Players: Ernesto Cavallini, Alessandro Carbonare American School (Boehm system) Description: Strong French influence but more open and wide, more air and flexibility Connections to jazz and film music Players: Larry Combs, Richard Stolzman, Charles Neidich, Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw JDG 20200815 The Most-used Types of Clarinets Band Eb Clarinet Bb Clarinet***** Eb Alto Clarinet Bb Bass Clarinet Eb Contra Alto Clarinet Bb Contra Bass Clarinet Orchestra Eb Clarinet C Clarinet Bb Clarinet A Clarinet Bb Bass Clarinet Worth Mentioning Basset Horn (in F) Basset Clarinet (in A) When an instrument plays its C and that sound/pitch is the same as the piano’s C, we say the instrument is “in C” When an instrument plays its C and that sound/pitch is the same as the piano’s Bb, we say the instrument is “in Bb” When an instrument plays its C and that sound/pitch is the same as the piano’s Eb, we say the instrument is “in Eb” And so on. JDG 20200815 Equipment Clarinets Rubber/plastic/ebonite, wood, carbon composites • Buffet • Selmer • LeBlanc • Yamaha • Bundy Mouthpieces Rubber, glass (metal) • Vandoren • Selmer • Yamaha • LeBlanc Reeds Cane or synthetic • Vandoren • Rico • Alexander • Gonzalez Ligatures and mouthpiece caps • Vandoren • Bonade (inverted) • LeBlanc • Rovner • Unnamed Tips • I purchase new instruments and used instruments. -

Bach's Goldberg Variations

Bach’s Goldberg Variations - A survey of the piano recordings by Ralph Moore Let me say right away that while I am well aware that Bach specified on the title page that these variations are for harpsichord, I much prefer them played on the modern piano in what is technically a transcription and venture to suggest that Bach would have loved the sonorities and flexibility of the modern instrument, even though it inevitably involves essentially faking the changes of register available on a double manual harpsichord. I hardly seem to be alone in this, in that, just as every great cellist wants to engage with the Cello Suites, so almost every great pianist seems to want to record his or her interpretation of the Goldbergs for posterity and the public appetite for recordings and performances on the pianoforte seems undiminished. I have accordingly confined this survey to that category; doubtless more authentic accounts on an original instrument have great merit but they lie beyond my scope, knowledge and experience; I have neither the acquaintance with, nor appreciation for, harpsichord versions to attempt a meaningful conspectus of them; nor, indeed, do I have the recording on my shelves and leave that task to a better-qualified reviewer. Here, however, is a good collective survey of the harpsichord recordings from The Classic Review aimed at the average punter like me. In common with many a devotee of this miraculous music, my own first encounter with it was via the second Glenn Gould recording when, many years ago, a cultivated girlfriend introduced me to it; it was love at first hearing (assisted, perhaps by my attachment to said lady, but that’s another story…). -

Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf194 No online items Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043 Finding aid prepared by Frank Ferko and Anna Hunt Graves This collection has been processed under the auspices of the Council on Library and Information Resources with generous financial support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] 2011 Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium ARS.0043 1 Collection ARS.0043 Title: Ambassador Auditorium Collection Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0043 Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Physical Description: 636containers of various sizes with multiple types of print materials, photographic materials, audio and video materials, realia, posters and original art work (682.05 linear feet). Date (inclusive): 1974-1995 Abstract: The Ambassador Auditorium Collection contains the files of the various organizational departments of the Ambassador Auditorium as well as audio and video recordings. The materials cover the entire time period of April 1974 through May 1995 when the Ambassador Auditorium was fully operational as an internationally recognized concert venue. The materials in this collection cover all aspects of concert production and presentation, including documentation of the concert artists and repertoire as well as many business documents, advertising, promotion and marketing files, correspondence, inter-office memos and negotiations with booking agents. The materials are widely varied and include concert program booklets, audio and video recordings, concert season planning materials, artist publicity materials, individual event files, posters, photographs, scrapbooks and original artwork used for publicity. -

Julian Bliss

Julian Bliss “unfailingly musical” Fanfare Magazine Biography Julian Bliss is one of the world’s finest solo clarinettists excelling as concerto soloist, chamber musician, jazz artist, masterclass leader and tireless musical explorer. He has inspired a generation of young players, as guest lecturer and creator of the Leblanc Bliss range of affordable clarinets, and introduced a large new audience to his instrument. The breadth and depth of Julian’s artistry are reflected in the diversity and distinction of his work. He has appeared with many of the world’s leading orchestras, including the London Philharmonic Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, and performed chamber music with Joshua Bell, Hélène Grimaud, Steven Isserlis, Steven Kovacevich and other great interpreters. Born in St Albans (UK), Julian began playing at the age of four. He moved to the United States in 2000 to study at Indiana University and subsequently received lessons from Sabine Meyer in Germany. Julian’s prodigious early career included performances at the prestigious Gstaad, Mecklenburg Vorpommern, Rheingau and Verbier festivals, and critically acclaimed debuts at London’s Wigmore Hall and New York’s Julian Bliss Lincoln Center. His first album for EMI Classics’ Debut series was greeted by five-star reviews and public praise following its release in 2003. Released on Signum Classics in September 2014, Julian’s live recording of the Mozart Clarinet Concerto with the Royal Northern Sinfonia was Classic FM disc of the week upon release. The release was accompanied by a performance at Classic FM Live at the Royal Albert Hall, London.