00 Copertina Ocp 2016 2 Extracta.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

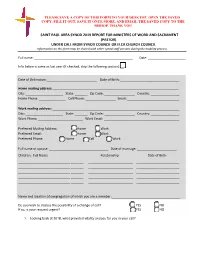

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

The Synod Process

The Synod Process I Convocation and Preparation of the Synod 2 Preparatory Commission 1 The bishop convenes the synod with the consultation of the • Members of the preparatory commission are chosen by the bishop. Presbyteral Council. • The preparatory commission assists the bishop in organizing and preparing for the synod. • The bishop establishes a synodal secretariat and possibly a press office. 1 2 4 Preparatory phases of synod • Spiritual, catechetical and formational preparation 4 1. All are invited to pray for the ongoing intention of the synod and its results, that it might become an authentic 3 event of grace for the Church. 3 Publication of the Synodal 2. All should be informed on the nature and Directory purpose of the synod and the scope of its The Synodal Directory includes: deliberations. 1. composition of the synod; • Diocesan Consultation 2. norms by which elections of synodal members are to be conducted; 1. The faithful and the clergy of the Diocese 3. various offices to be exercised by the synod; are encouraged to express their needs, 4. procedural norms of the synod meetings. desires, challenges and opinions regarding the synod topics. 2. Meetings will take place at each parish, then deanery, to discuss synod topics. II Conducting the Synod • Determining the questions 1. The bishop determines the • The actual synod consists of the synodal sessions, questions on which the synodal typically in the cathedral. debate will concentrate. • Members of the synod make the profession of the faith before commencing synodal discussions. • Themes to be examined are introduced from a brief report; discussion begins. -

The Synod for the Amazon

THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON Marcelo Barros • The divine revelation that arrives late1 • ABSTRACT It is good news that the Synod of Catholic Bishops from around the world, convened by Pope Francis and which will take place in October in Rome, has been prepared with extensive consultation with Amazonian communities and civil organizations working with them. The novelty of this Synod is the call for the Church, instead of acting as a teacher, to listen and hear the voice of the Amazon. In doing so, the Church will discover how to confront the challenges and new possibilities for its mission; a new vision and in opposition to the colonization in which it was complicit. KEYWORDS Spiritual listening | Catholic Church | Earth cry | Amazon peoples | Walk together • SUR 29 - v.16 n.29 • 133 - 138 | 2019 133 THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON There is no doubt that for the peoples of the Amazon, the news that Pope Francis convoked a Synod of Roman-Catholic Bishops from around the world to reflect about the appeals that the Amazon is making to the Universal Church (the body of Christian churches worldwide) was well-received. As Dom Roque Paloschi, president of the Indigenist Missionary Council in Brazil (Conselho Indigenista Missionário - CIMI), affirmed, “the Synod for the Amazon practically began in January of 2018, in Puerto Maldonado (Peru), during the Pope’s meeting with Amazonian people.”2 The Synod of Bishops is an institution that continues an old church custom and enacts the Church’s vocation as a sign and instrument of unity for all of humanity. -

1 Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent Christians Believe That The

Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent1 Christians believe that the Persons of the Trinity are distinct but in every respect equal. We believe also that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father. It is difficult to reconcile claims about the Father’s role as the progenitor of Trinitarian Persons with commitment to the equality of the persons, a problem that is especially acute for Social Trinitarians. I propose a metatheological account of the doctrine of the Trinity that facilitates the reconciliation of these two claims. On the proposed account, “Father” is systematically ambiguous. Within economic contexts, those which characterize God’s relation to the world, “Father” refers to the First Person of the Trinity; within theological contexts, which purport to describe intra-Trinitarian relations, it refers to the Trinity in toto-- thus in holding that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father we affirm that the Trinity is the source and unifying principle of Trinitarian Persons. While this account solves a nagging problem for Social Trinitarians it is theologically minimalist to the extent that it is compatible with both Social Trinitarianism and Latin Trinitarianism, and with heterodox Modalist and Tri-theist doctrines as well. Its only theological cost is incompatibility with the Filioque Clause, the doctrine that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son—and arguably that may be a benefit. 1. Problem: the equality of Persons and asymmetry of processions In addition to the usual logical worries about apparent violations of transitivity of identity, the doctrine of the Trinity poses theological problems because it commits us to holding that there are asymmetrical quasi-causal relations amongst the Persons: the Father “begets” the Son and “spirates” the Holy Spirit. -

Synodality” – Results and Challenges of the Theological Dialogue Between the Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church

“SYNODALITY” – RESULTS AND CHALLENGES OF THE THEOLOGICAL DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH Archbishop Job of Telmessos I. The results of the Joint International Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church The Joint International Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church has been focusing on the topic of “Primacy and Synodality” over the last twelve years. This is not surprising, since the issue of the exercise of papal primacy has been an object of disagreement between Orthodox and Catholics over a millennium. The Orthodox contribution has been to point out that primacy and synodality are both inseparable: there cannot be a gathering (synodos) without a president (protos), and no one cannot be first (protos) if there is no gathering (synodos). As the Metropolitan of Pergamon, John Zizioulas, pointed out: “The logic of synodality leads to primacy”, since “synods without primates never existed in the Orthodox Church, and this indicates clearly that if synodality is an ecclesiological, that is, dogmatical, necessity so must primacy [be]”1. The Ravenna Document (2007) The document of the Joint International Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church, referred as the “Ravenna Document” (2007), speaks of synodality and conciliarity as synonyms, “as signifying that each member of the Body of Christ, by virtue of baptism, has his or her place and proper responsibility in eucharistic koinonia (communio in Latin)”. It then affirms that “conciliarity reflects the Trinitarian mystery and finds therein its ultimate foundation”2 and from there, considers that “the Eucharist manifests the Trinitarian koinônia actualized in the faithful as an organic unity of several members each of whom has a charism, a service or a proper ministry, necessary in their variety and diversity for the edification of all in the one ecclesial Body of Christ”3. -

Summary History of the Synod of the West

Summary History of the Synod of the West By Joseph L. Mihelic, and Lightly edited by Joel L. Samuels Introduction German Presbyterianism in the Upper Mississippi Valley may be said to have begun with the coming of the Rev. and Mrs. Peter Flury to Dubuque, Iowa in the fall of 1846. Peter Flury was a Swiss-German and his wife Sophie Jackson Flury was English from Brighton, England. After serving a pastorate in Schiers, Switzerland, Pastor Flury and his wife decided to come to America as missionaries to American Indians, and applied to the American Mission Board for an assignment. The Board, however, commissioned him in October 1846 and sent him to Dubuque, Iowa where there was a colony of Swiss-German immigrants who had asked the American Mission Board for a pastor. The Flurys came to Dubuque in the fall of 1846 and rented a house in which they began a school for the children and adults of the Swiss immigrants, as well as anyone who was interested in learning German and English and the Christian religion. The school was free and open to Protestants and Roman Catholics. On Christmas Day of 1847, Flury organized a congregation of thirty-five charter members and called this congregation the German Evangelical Church. He provided it also with a Constitution which he modeled after the Reform Church of Switzerland, the Church which he served at Schiers, Switzerland. This constitution has been preserved in the Kirchenbuch (“church-book”) of the congregation and shows Flurys’ concern for the correct order in the operation of the congregation's business, as well as his interest in education of both children and adults. -

A Review of Dissident Sacramental Theology

A REVIEW OF DISSIDENT SACRAMENTAL THEOLOGY Five years ago it was my privilege to address this Society, making a cursory review of the main points on which Catholics and Orthodox disagree in the realm of dogmatic theology. These points are neither too numerous nor too difficult to preclude a harmonious solution. The most fundamental issue is the primacy of the pope. But even here, since the Orthodox already believe in the infallibility of the Church and in an honorary primacy of the Bishop of Rome in that Church, it might not be too sanguine to posit the possibility of arriving at an understanding of the pope as the mouthpiece of the infallible Church. This year the officers of the Society have requested a review of Orthodox sacramental practice in the hope that this might furnish some summary of Orthodox moral theology by providing a glimpse of the actual religious life in an Orthodox parish, as well as bring- ing our Catholic theologians up to date on the practical questions they must face regarding intercommunion if any reunion should ever be achieved. At the outset we should express the caution that in this practical as well as in the theoretical sphere, we must beware of absolute predications—because there is apt to be a divergency of practice between the various national groups of Orthodox and even within the same national group. The chief bodies of Orthodox—at least as far as theological leadership is concerned—are the Greeks and the Russians. Usually the Syrian and Albanian Orthodox will follow Greek practice, while the various Slav groups like the Serbs, Bulgars and Ukrainians will be content to follow the hegemony of the Russian Orthodox Church. -

The Diocesan Synod

The Diocesan Synod A Brief Summary of the Institution of the Diocesan Synod and A Preview of our Second Diocesan Synod Definition of a Synod An assembly or “coming together” of the local Church. Code of Canon Law c. 460 A diocesan synod is a group of selected priests and other members of the Christian faithful of a particular church who offer assistance to the diocesan bishop for the good of the whole diocesan community... Purpose of a Synod What’s the purpose of a Diocesan Synod? 1. Unity – brings the Diocese together 2. Reform and Renewal o Teaching o Spirituality 3. Assess/Implement Best Practices o Pastoral o Financial 4. Communicate Info – from Rome/USCCB 5. Legislate practical Norms o To aid: Pastors, Vicars, Business Managers, Parish Secretaries, Diocesan Officials, Lay faithful, etc… Purpose of a Synod What a Synod is not… A Diocesan Synod is not a ‘be all to end all’ pastoral plan Rather, a Diocesan Synod is intended to meet the current practical needs of the Church and is to be renewed when those needs change (~ 8-10 years) A Synod provides (when needed) pastoral and administrative ‘housecleaning’. First Diocesan Synods Rooted in 2 ancient practices The presbyterate meeting to share in the governance of the local church Bishops of an area/province gathering to address issues of common concern Why were they needed? Heresies threatened Church Teaching Schisms threatened Church Unity Lax Behavior (clergy:) threatened Evangelization First Diocesan Synods Historically, Dioceses were more so municipal, city- centered entities with the Bishop and his clergy being located very closely geographically. -

The Word-Of-God Conflict in the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod in the 20Th Century

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Master of Theology Theses Student Theses Spring 2018 The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century Donn Wilson Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Donn, "The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century" (2018). Master of Theology Theses. 10. https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Theology Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE WORD-OF-GOD CONFLICT IN THE LUTHERAN CHURCH MISSOURI SYNOD IN THE 20TH CENTURY by DONN WILSON A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Luther Seminary In Partial Fulfillment, of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY THESIS ADVISER: DR. MARY JANE HAEMIG ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr. Mary Jane Haemig has been very helpful in providing input on the writing of my thesis and posing critical questions. Several years ago, she guided my independent study of “Lutheran Orthodoxy 1580-1675,” which was my first introduction to this material. The two trips to Wittenberg over the January terms (2014 and 2016) and course on “Luther as Pastor” were very good introductions to Luther on-site. -

Information About on Leave from Call Status from the ELCA Roster

B. On Leave from Call 7.31.07. On Leave from Call. A minister of Word and Sacrament of this church, serving under a regularly issued letter of call, who leaves the work of that ministry without accepting another regularly issued letter of call, may be retained on the roster of Ministers of Word and Sacrament of this church, upon endorsement by the synod bishop, by action of the Synod Council in the synod of which the minister of Word and Sacrament is a member, under policy developed by the appropriate churchwide unit, reviewed by the Conference of Bishops, and adopted by the Church Council. a. Normative Pattern: By annual action of the Synod Council in the synod of which a member, upon endorsement by the synod bishop, a minister of Word and Sacrament who is without a current letter of call may be retained on the roster of Ministers of Word and Sacrament of this church for a maximum of three years, beginning at the completion of an active call. b. Study Leave: By annual action of the Synod Council in the synod of which a member, with the approval of the synod bishop and in consultation with the appropriate churchwide unit, a minister of Word and Sacrament engaged in graduate study, in a field of study that will enhance service in the ministry of Word and Sacrament, may be retained on the roster of Ministers of Word and Sacrament of this church for a maximum of six years. c. Family Leave: A minister of Word and Sacrament may request leave for family responsibilities. -

Sharing the Gospel of Salvation

GS Misc 956 Sharing the Gospel of Salvation Foreword The gospel testifies to the uniqueness of Jesus Christ in God’s plan for the salvation of the world. There can be no greater theme – and no higher calling for the Church than to bear witness to salvation in and through Christ. One might think that any attempt to address a matter of such magnitude in the thin pages of a Synod report is sure to be inadequate and, indeed, there is much that this report does not, and cannot do. Nevertheless, it is a timely and important report because it addresses the day to day impact of Christian doctrine on the life of the Church and our relationship with the people and cultures around us. There is often a gap between the great declarations of Christian doctrine and the practical outworking of belief in the daily discipleship of Christian men and women and the communities they create and inhabit. The gap is not so much one of inconsistency but one of understanding the connections. The Church in every age must give close attention to how it lives as a neighbour amongst others, and how such neighbourliness is informed and shaped by its overarching beliefs about the nature of God and Christ’s transformation of the world. This report is a bridge between what we believe about God’s saving work in Christ and the practical implications for discipleship in a world made profoundly complex and confusing by rapid change and a deepening appreciation of social, cultural and religious plurality. When Mr Paul Eddy moved the Private Member’s Motion at General Synod which led to this report, he was supported, both on the platform and in the debate itself, by Synod members from right across the range of doctrine and practice within the Church of England. -

1 Common Formula on Christology Mixed Commission of the Dialogue

Common formula on Christology Mixed Commission of the Dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Coptic Orthodox Church "The Mystery of Redemption and Its Consequences for the Last Ends of the Human Person" FULL TEXT Report In the love of God the Father, by the grace of the Only Begotten Son, and by the gift of the Holy Spirit. On Friday, the 12th of February 1988, the mixed commission of the dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Coptic Orthodox Church met in the Monastery of Saint Bishoy, Wadi El Natrun, in Egypt. His Holiness Pope Shenouda III opened the meeting by prayer. His Excellency Giovanni Moretti, the Apostolic Pro Nuncio in Egypt, and Reverend Father Pierre Duprey, Secretary of the Vatican Secretariate for Promoting Christian Unity, attended this meeting representing His Holiness Pope John Paul II and enabled to sign this agreement. Also bishops delegated by His Beatitude Stephanos II Ghattas, Patriarch of the Coptic Catholic Church, were present and delegated to sign this agreement. We have rejoiced at the historical meeting that happened in the Vatican on May 1973, between His Holiness Pope Paul VI and His Holiness Pope Shenouda III. This was the first meeting since about 15 centuries between our two Churches. In that meeting we found ourselves in agreement on many issues of faith. In that meeting also a mixed commission was formed to discuss the issues of difference of doctrine and faith between the two Churches aiming at church unity. Previously in Vienna, September 1971, Pro Oriente arranged a meeting between theologians of the Catholic Church and those of the Oriental Orthodox Churches: the Coptic, the Syrian, the Armenian, the Ethiopian, and the Indian.