“The Assurance of Salvation in the Canons of Dort: a Commemorative Essay” (Part One)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Five Points of Calvinism

• TULIP The Five Points of Calvinism instructor’s guide Bethlehem College & Seminary 720 13th Avenue South Minneapolis, MN 55415 612.455.3420 [email protected] | bcsmn.edu Copyright © 2007, 2012, 2017 by Bethlehem College & Seminary All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, modified, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Scripture taken from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. Copyright © 2007 by Crossway Bibles, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. • TULIP The Five Points of Calvinism instructor’s guide Table of Contents Instructor’s Introduction Course Syllabus 1 Introduction from John Piper 3 Lesson 1 Introduction to the Doctrines of Grace 5 Lesson 2 Total Depravity 27 Lesson 3 Irresistible Grace 57 Lesson 4 Limited Atonement 85 Lesson 5 Unconditional Election 115 Lesson 6 Perseverance of the Saints 141 Appendices Appendix A Historical Information 173 Appendix B Testimonies from Church History 175 Appendix C Ten Effects of Believing in the Five Points of Calvinism 183 Instructor’s Introduction It is our hope and prayer that God would be pleased to use this curriculum for his glory. Thus, the intention of this curriculum is to spread a passion for the supremacy of God in all things for the joy of all peoples through Jesus Christ. This curriculum is guided by the vision and values of Bethlehem College & Seminary which are more fully explained at bcsmn.edu. At the Bethlehem College & Semianry website, you will find the God-centered philosophy that undergirds and motivates everything we do. -

Unconditional Election True Or False?

“U” – Unconditional Election True or False? Bible Answers About Denominations “Unconditional election” is the second of five major errors in John Calvin’s system of doctrine which we have come to identify by the familiar acrostic of the word “tulip.” The “T” stands for Total Hereditary Depravity and is discussed in the tract by that name in this series. The “U” stands for Unconditional Election which teaches that God arbitrarily selected a certain number of people to be saved. In other words, God, from all eternity, unchangeably foreordained, or predestinated, or elected all that will be in heaven with Him, and all that will be in Hell with the devil. It does not matter whether man strives to do good or is content to do evil because this election is strictly unconditional. John Calvin wrote: “Predestination, by which God adopts some to the hope of life, and adjures others to eternal death, no one, desirous of the credit of piety, dares abso- lutely to deny....Predestination we call the eternal decree of God, by which He has determined in Himself what He would have to become of every individual of mankind. For they are not all created with a similar destiny; but eternal life is fore-ordained for some, and eternal damnation for others. Every man, therefore, being created for one or the other of these ends, we say, is predestined either to life or to death. This God has not only testified in particular persons, but has given as specimen of it in the whole posterity of Abraham, which should evidently show the future condition of every nation to depend upon His decision.” (Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church Vol. -

What Is Irresistible Grace and Is It Biblical? Heather Riggleman | Crosswalk.Com Contributing Writer 2021 5 Jul

What Is Irresistible Grace and Is it Biblical? Heather Riggleman | Crosswalk.com Contributing Writer 2021 5 Jul Photo credit: ©iStock/Getty Images Plus/Anastasiia Stiahailo Have you ever wondered why one person believes in God and another totally rejects Him? Some would say it has to do with irresistible grace. While it sounds like a decadent dessert that no person can deny, irresistible grace is something only God can do. Irresistible grace is defined as those whom God has elected and drawn to Himself. When God calls the elect, they respond (John 6:37, 44; 10:16). I remember very clearly how I thought the Bible, God, church, and all the things in between were stuffy, legalistic, and limiting to living life. I used to think God was just a crutch for weak people. But during my college years, God overcame my resistance to Him. God made Jesus look so compelling that He overcame my resistance, He broke through my barriers and I not only came freely to Him—I ran to Him with every fiber of my being. I came alive in Christ at the age of 23 because of His irresistible grace. Like you, I had been resisting God all my life until the Holy Spirit opened my eyes to the most compelling sight: Jesus, the cross, and God’s beautiful gift to be His daughter. Up until that moment, I was a slave to sin, dead on my feet. God’s irresistible grace means that you were dead in your sins. You were dead, living your life as a blind, rebellious lover of this world. -

Calvinism and Limited Atonement Isaiah 53:6; Hebrews 2:9 and Others

CALVINISM AND LIMITED ATONEMENT ISAIAH 53:6; HEBREWS 2:9 AND OTHERS Text: Isaiah 53:6; Hebrews 2:9 Isaiah 53:6 6 All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and the LORD hath laid on him the iniquity of us all. Hebrews 2:9 9 But we see Jesus, who was made a little lower than the angels for the suffering of death, crowned with glory and honour; that he by the grace of God should taste death for every man. Introduction: Of the five points of Calvin’s philosophy, (and I call it "philosophy" instead of "theology" because in this particular point, it is 100% contrary to the revealed will of God as given to us in the Bible, therefore, it cannot properly be called "theology") the weakest link is his so-called false teaching on the "LIMITED ATONEMENT," or the "L" of the T.U.L.I.P. acronym of Calvinism. - 1 - It is interesting to me that this point is the center of this deadly flower. We will consider the Basic Definition, Blatant Distortion, and the Biblical Dispute, of Limited Atonement. 1. BASIC DEFINITION OF LIMITED ATONEMENT By “Limited Atonement” we refer to the belief which states that Christ did not die for “all or everyone” but rather died only for the elect. While it is true that only the saved benefit from Christ’s death on the cross, Christ died for all people. 1 John 2:1-2 1 My little children, these things write I unto you, that ye sin not. -

Total Depravity

TULIP: A FREE GRACE PERSPECTIVE PART 1: TOTAL DEPRAVITY ANTHONY B. BADGER Associate Professor of Bible and Theology Grace Evangelical School of Theology Lancaster, Pennsylvania I. INTRODUCTION The evolution of doctrine due to continued hybridization has pro- duced a myriad of theological persuasions. The only way to purify our- selves from the possible defects of such “theological genetics” is, first, to recognize that we have them and then, as much as possible, to set them aside and disassociate ourselves from the systems which have come to dominate our thinking. In other words, we should simply strive for truth and an objective understanding of biblical teaching. This series of articles is intended to do just that. We will carefully consider the truth claims of both Calvinists and Arminians and arrive at some conclusions that may not suit either.1 Our purpose here is not to defend a system, but to understand the truth. The conflicting “isms” in this study (Calvinism and Arminianism) are often considered “sacred cows” and, as a result, seem to be solidified and in need of defense. They have become impediments in the search for truth and “barriers to learn- ing.” Perhaps the emphatic dogmatism and defense of the paradoxical views of Calvinism and Arminianism have impeded the theological search for truth much more than we realize. Bauman reflects, I doubt that theology, as God sees it, entails unresolvable paradox. That is another way of saying that any theology that sees it [paradox] or includes it is mistaken. If God does not see theological endeavor as innately or irremediably paradoxical, 1 For this reason the author declines to be called a Calvinist, a moderate Calvinist, an Arminian, an Augustinian, a Thomist, a Pelagian, or a Semi- Pelagian. -

Calvinism Vs Wesleyan Arminianism

The Comparison of Calvinism and Wesleyan Arminianism by Carl L. Possehl Membership Class Resource B.S., Upper Iowa University, 1968 M.C.M., Olivet Nazarene University, 1991 Pastor, Plantation Wesleyan Church 10/95 Edition When we start to investigate the difference between Calvinism and Wesleyan Arminianism, the question must be asked: "For Whom Did Christ Die?" Many Christians answer the question with these Scriptures: (Failing, 1978, pp.1-3) JOH 3:16 For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life. (NIV) We believe that "whoever" means "any person, and ...that any person can believe, by the assisting Spirit of God." (Failing, 1978, pp.1-3) 1Timothy 2:3-4 This is good, and pleases God our Savior, (4) who wants all men to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth. (NIV) 2PE 3:9 The Lord is not slow in keeping his promise, as some understand slowness. He is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance. (NIV) REV 22:17 The Spirit and the bride say, "Come!" And let him who hears say, "Come!" Whoever is thirsty, let him come; and whoever wishes, let him take the free gift of the water of life. (NIV) (Matthew 28:19-20 NIV) Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, (20) and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. -

Foundations of Discipleship

FOUNDATIONS FOR DISCIPLESHIP Systematic Theology Course Dr. William E. Bell INTRODUCTION This comprehensive course on the Doctrines of the Scriptures represents a complete study necessary for building a secure Biblical foundation into your life as a disciple of Jesus Christ. The Foundations For Discipleship Course consists of nine volumes, each of which is subdivided into twelve 45-minute audio units. Each unit is accompanied and supplemented by a downloadable study guide. Listen carefully to each audio message, and follow along in the printed material. Make notes on your printed study guide as needed, to help you grasp and retain the material. This will become your own personal notebook and can be used in training others. When needed, replay sections that you did not grasp the first time. It may be that the information is entirely new to you and needs to be run past you again, or perhaps you find that your mind wandered a bit. The great advantage of digital material over a live lecture is this flexibility of time, place and replay capabilities. The normal pace is one unit per week with the entire course taking two years to complete. The pace may be accelerated cautiously if you desire, but should be kept modest enough so not to hinder comprehension. Ideally, the course would be done in a small-group setting where each participant works through a specific unit on a given weekend. The Bible study group would then meet during the week to listen to that weeks audio unit again together accompanied by a time of sharing notes, discussion and prayer together. -

The Nature and Extent of the Atonement in Lutheran

THE N A T U R E A N D E X T E N T O F T H E ATONEMENT I N L U T H E R A N T H E O L O G Y DAVID SCAER, TH.D. I. The Problem The· conflict concerning the nature and extent of the atonement arose in Christian theology because of attempts to reconcile rationally apparently conflicting statements in the Holy Scriptures on the atone- ment and election. Briefly put, passages relating to the atonement are universal in scope including all men and those relating to election apply only to a limited number. Basically there have been three approaches to this tension between a universal atonement and a limited election. One approach is to understand the atonement in light of the election. Since obviously there are many who are not eventually saved, the atonement offered by Christ really applied not to them but only to those who are finally saved, i.e., the elect. This is the Calvinistic or Reformed view. The second approach understands the election in light of the atonement. This view credits each individual with the ability to make a choice of his own free will to believe in Christ. Since Christ died for all men and since man is responsible for his own damnation, therefore he at least cooperates with the Holy Spirit in coming to faith. This is the Arminian or synergistic view, also widely held in Methodism. The third view* is that of classical Lutheran theology. This position as set down in the Formula of Concord (1580) does not attempt to resolve what the Holy Scriptures state con- cerning atonement and election. -

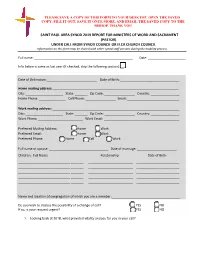

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

The Synod of Dort, the Westminster Assembly, and the French Reformed Church, 1618-431 MICHAEL DEWAR

The Synod of Dort, the Westminster Assembly, and the French Reformed Church, 1618-431 MICHAEL DEWAR The European Background In an age of ecumenical councils, from 'Edinburgh, 1910' and 'Amsterdam, 1948' to 'Vatican II', and beyond, it is often forgotten that the Reformers, insular and continental, were no less 'ecumenically' minded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Richard Baxter wrote, 'The Christian world, since the days of the Apostles, had never a Synod of more excellent divines, taking one thing with another, than this [of Westminster] and the Synod of Dort. '2 These were the nearest to the Council of Trent that Protes tantism was to see. Yet earlier correspondence between Geneva and Canterbury shows that closer union might have been possible three generations before. Calvin had written to Cranmer, 'if I can be of any service, I shall not shrink from crossing ten seas, if need be for that object' ,3 (that is, of uniting the Reformed Churches). This was in 1552, the 'high tide' of Anglican Reformation, with Melanchthon and Bull inger for Cranmer's 'Lambeth Confere~e· also. It is tragic that this ideal, so broadly based on international and eirenic lines, came to nothing until Protestantism at home and abroad was hopelessly divided. For it cannot be urged that the 'Dordrace nists' and the Westminster Fathers were other than polemical in their intentions, and divisive in their results. The sixteenth century left the Reformed Churches inclusive and international. The seventeenth century left them enfeebled but embattled, exclusive and nationalistic. The Synod of Dort, 1618 Inevitably Calvinism was closely equated with Netherlands National ism. -

"Calvinism Vs. Arminianism" by Mary Fairchild Updated July 03, 2019 One of the Most Potentially Divisive Debates in Th

"Calvinism Vs. Arminianism" By Mary Fairchild Updated July 03, 2019 One of the most potentially divisive debates in the history of the church centers around the opposing doctrines of salvation known as Calvinism and Arminianism. Calvinism is based on the theological beliefs and teaching of John Calvin (1509-1564), a leader of the Reformation, and Arminianism is based on the views of Dutch theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560-1609). After studying under John Calvin's son-in-law in Geneva, Jacobus Arminius started out as a strict Calvinist. Later, as a pastor in Amsterdam and professor at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, Arminius' studies in the book of Romans led to doubts and rejection of many Calvinistic doctrines. In summary, Calvinism centers on the supreme sovereignty of God, predestination, the total depravity of man, unconditional election, limited atonement, irresistible grace, and the perseverance of the saints. Arminianism emphasizes conditional election based on God's foreknowledge, man's free will through prevenient grace to cooperate with God in salvation, Christ’s universal atonement, resistible grace, and salvation that can potentially be lost. What exactly does all this mean? The easiest way to understand the differing doctrinal views is to compare them side by side. Compare Beliefs of Calvinism Vs. Arminianism God's Sovereignty The sovereignty of God is the belief that God is in complete control over everything that happens in the universe. His rule is supreme, and his will is the final cause of all things. Calvinism: In Calvinist thinking, God's sovereignty is unconditional, unlimited, and absolute. All things are predetermined by the good pleasure of God's will. -

The Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal

FALL 2019 volume 6 issue 1 3 FROM RUTHERFORD HALL Dr. Barry J. York 4 FOUR CENTURIES AGO: AN HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE SYNOD OF DORT Dr. David G. Whitla 16 THE FIRST HEADING: DIVINE ELECTION AND REPROBATION Rev. Thomas G. Reid, Jr. 25 THE SECOND HEADING - CHRIST’S DEATH AND HUMAN REDEMPTION THROUGH IT: LIMITED ATONEMENT AT THE SYNOD OF DORDT AND SOME CONTEMPORARY THEOLOGICAL DEBATES Dr. Richard C. Gamble 33 THE THIRD HEADING: HUMAN CORRUPTION Rev. Keith A. Evans 39 THE FOURTH HEADING: “BOTH DELIGHTFUL AND POWERFUL” THE DOCTRINE OF IRRESISTIBLE GRACE IN THE CANONS OF DORT Dr. C. J. Williams 47 THE FIFTH HEADING: THE PERSEVERANCE OF THE SAINTS Dr. Barry J. York STUDY UNDER PASTORS The theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary Description Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is provided freely by RPTS faculty and other scholars to encourage the theological growth of the church in the historic, creedal, Reformed faith. Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal is published biannually online at the RPTS website in html and pdf. Readers are free to use the journal and circulate articles in written, visual, or digital form, but we respectfully request that the content be unaltered and the source be acknowledged by the following statement. “Used by permission. Article first appeared in Reformed Presbyterian Theological Journal, the online theological journal of the Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary (rpts.edu).” e d i t o r s General Editor: Senior Editor: Assistant Editor: Contributing Editors: Barry York Richard Gamble Jay Dharan Tom Reid [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] C.