1 Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent Christians Believe That The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

21.05.30 the Holy Trinity

TRINITY SUNDAY 135 NE Randolph Avenue, Peoria, Illinois 61606 Online: www.trinitypeoria.com ~ (309) 676-4609 The Holy Trinity May 30, 2021 Sunday Worship 8:00, 9:30 and 11:00 a.m. WELCOME IN THE NAME OF OUR RISEN LORD Welcome to Trinity! Today in the Divine Service God proclaims to us through Word and Sacrament the forgiveness, love, and salvation that He has won for us through the death and resurrection of His Son Jesus Christ. LARGE PRINT BULLETINS are available from an usher for persons with vision difficulties. WORSHIPPING WITH OUR CHILDREN This week we celebrate God as the Trinity. The word “Trinity” means “three.” For Christians the word helps us understand that God shows Himself to us as “Father, Son and Holy Spirit.” He is three persons in one God. Only He can do that! It is hard for us to understand exactly how God works but the one thing we know for sure is that God the Father loves us so much that God the Son, Jesus, was sent to give His life to pay for our sins and then rose to life again so that we could live forever. God the Holy Spirit, many times shown as a dove, gives us faith to believe that God loves us this much! See how many triangles you can find in church. Ideas adapted from Kids in the Divine Service by Christopher I. Thoma. ©2000 by the Commission on Worship of The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. All rights reserved. Divine Service - Setting Two + We Come Into God’s Presence + In celebration of Trinity Sunday, we will confess the Athanasian Creed separated into four parts throughout our liturgy. -

Our Lady of the Ozarks Catholic Church

May 30, 2021 Bulletin – Most Holy Trinity Sunday Our Lady of the Ozarks Catholic Church 951 Swan Valley Drive Forsyth, MO 65653 phone: 417.546.5208 www.ourladyoftheozarks.com email: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday, Wednesday & Friday 8:00 am to 2:00 pm Weekend Mass Time: Sunday 8:30 am Father David Hulshof Weekday Mass Times: Wednesday & Friday 9:00 am Pastor Sacrament of Reconciliation: Sundays before Mass, Wednesdays after Mass 417-334-2928 Holy Hour Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament: Wednesdays after Mass [email protected] Father Samson Dorival Associate Pastor 417-334-2928 [email protected] Deacon Daniel Vaughn Pastoral Associate 417-546-5208 or 812-204-2625 [email protected] Marilyn Guy Financial Administrator Nancy Loughner Office Assistant Laura Cairns Music Ministry Welcome Blessings from our parish family Whether you are visiting for a short while, have moved here and are joining our parish, or are returning to your Catholic Faith, we want to welcome you to Our Lady of the Ozarks Church. Our parish is committed to inviting and supporting every parishioner to become a disciple of Christ, building His Kingdom through prayer, fellowship and service to others. We encourage you to connect with the people and ministries of our parish Our Lady of the Ozarks Mission Statement community and look forward to We are a unique parish called together from far and near. We bring meeting you personally. our talents and our shortcomings, our histories, and our hopes. Please call the parish office and Most of all, we bring our faith, and together in this faith we grow in let the friendship begin. -

SACRAMENTAL THEOLOGY and ECCLESIASTICAL AUTHORITY Dmusjankiewicz Fulton College Tailevu, Fiji

Andn1y.r Uniwr~itySeminary Stndics, Vol. 42, No. 2,361-382. Copyright 8 2004 Andrews University Press. SACRAMENTAL THEOLOGY AND ECCLESIASTICAL AUTHORITY DmusJANKIEWICZ Fulton College Tailevu, Fiji Sacramental theology developed as a corollary to Christian soteriology. While Christianity promises salvation to all who accept it, different theories have developed as to how salvation is obtained or transmitted. Understandmg the problem of the sacraments as the means of salvation, therefore, is a crucial soteriological issue of considerable relevance to contemporary Christians. Furthermore, sacramental theology exerts considerable influence upon ecclesiology, particularb ecclesiasticalauthority. The purpose of this paper is to present the historical development of sacramental theology, lea- to the contemporary understanding of the sacraments within various Christian confessions; and to discuss the relationship between the sacraments and ecclesiastical authority, with special reference to the Roman Catholic Church and the churches of the Reformation. The Development of Rom Catholic Sacramental Tbeohgy The Early Church The orign of modem Roman Catholic sacramental theology developed in the earliest history of the Christian church. While the NT does not utilize the term "~acrament,~'some scholars speculate that the postapostolic church felt it necessary to bring Christianity into line with other rebons of the he,which utilized various "mysterious rites." The Greek equivalent for the term "sacrament," mu~tmbn,reinforces this view. In addition to the Lord's Supper and baptism, which had always carried special importance, the early church recognized many rites as 'holy ordinances."' It was not until the Middle Ages that the number of sacraments was officially defked.2 The term "sacrament," a translation of the Latin sacramenturn ("oath," 'G. -

2. the Sacrament of Marriage and Its Impediments

THE SACRAMENT OF MARRIAGE AND ITS IMPEDIMENTS I. On Orthodox Marriage 1. The institution of the family is threatened today by such phenomena as secularization and moral relativism. The Orthodox Church maintains, as her fundamental and indisputable teaching, that marriage is sacred. The freely entered union of man and woman is an indispensable precondition for marriage. 2. In the Orthodox Church, marriage is considered to be the oldest institution of divine law because it was instituted simultaneously with the creation of Adam and Eve, the first human beings (Gen 2:23). Since its origin, this union not only implies the spiritual communion of a married couple—a man and a woman—but also assured the continuation of the human race. As such, the marriage of man and woman, which was blessed in Paradise, became a holy mystery, as mentioned in the New Testament where Christ performs His first sign, turning water into wine at the wedding in Cana of Galilee, and thus reveals His glory (Jn 2:11). The mystery of the indissoluble union between man and woman is an icon of the unity of Christ and the Church (Eph 5:32). 3. Thus, the Christocentric typology of the sacrament of marriage explains why a bishop or a presbyter blesses this sacred union with a special prayer. In his letter to Polycarp of Smyrna, Ignatius the God-Bearer stressed that those who enter into the communion of marriage must also have the bishop’s approval, so that their marriage may be according to God, and not after their own desire. -

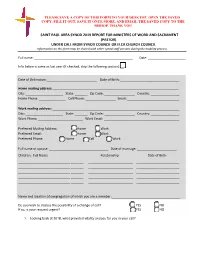

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

The Sacrament of Marriage and Its Impediments

The Canadian Journal of Orthodox Christianity Volume XI, Number 2, Spring 2016 The Sacrament of Marriage and Its Impediments The Synaxis of Primates of Local Orthodox Churches1 1. Orthodox Marriage 1) The institute of family is threatened today by such phenomena as secularization and moral relativism. The Orthodox Church asserts the sacral nature of marriage as her fundamental and indisputable doctrine. The free union of man and woman is an indispensable condition for marriage. 2) In the Orthodox Church, marriage is considered to be the oldest institution of divine law since it was instituted at the same time as the first human beings, Adam and Eve, were created (Gen. 2:23). Since its origin this union was not only the spiritual communion of the married couple – man and woman, but also assured the continuation of the human race. Blessed in Paradise, the marriage of man and woman became a holy mystery, which is mentioned in the New Testament in the story about Cana of Galilee, where Christ gave His first sign by turning water into wine thus revealing His glory (Jn. 2:11). The mystery of the indissoluble union of man and woman is the image of the unity of Christ and the Church (Eph. 5:32). 1 The document is approved by the Synaxis of the Primates of Local Orthodox Churches on January 21 – 28, 2016, in Chambesy, with the exception of representatives of the Orthodox Churches of Antioch and Georgia. 40 The Canadian Journal of Orthodox Christianity Volume XI, Number 2, Spring 2016 3) The Christ-centered nature of marriage explains why a bishop or a presbyter blesses this sacred union with a special prayer. -

The Athanasian Creed

The Athanasian Creed So likewise the Father is almighty, For the right faith is that we believe the Son almighty, and the Holy and confess that our Lord Jesus Christianity constantly struggles to keep the Faith free from false Spirit almighty. Christ, the Son of God, philosophies. And yet They are not three is God and man; In Fourth Century Alexandria, Egypt, a persuasive preacher with a logical almighties but One Almighty. God of the substance of the Father, mind used a philosophical concept foreign to the Scriptures in order to explain So the Father is God, the Son is begotten before the worlds; the connection between Jesus and his Father. Arius borrowed from the popular God, and the Holy Spirit is God. and man of the substance of His And yet They are not three mother, born in the world. Greek concept that a “god,” by nature, had to be high, distant and almighty; Gods but one God. Perfect God and perfect man, of a reason- and that humans, consequently, had to be low, spatial and inferior. So likewise the Father is Lord, the able soul and human flesh subsisting. Arius taught that only the Father was really a proper God. Because Jesus Son Lord, and the Holy Spirit Lord. Equal to the Father as touching was human, he was therefore only a creature (created by God) and therefore And yet They are not three His Godhead and inferior to the did not really possess any divine qualities. Lords but One Lord. Father as touching His The problem: when Arius denied the divinity of Christ, he destroyed God’s For as we are compelled by the manhood; role in accomplishing our salvation. -

Chapter 1 the Trinity in the Theology of Jürgen Moltmann

Our Cries in His Cry: Suffering and The Crucified God By Mick Stringer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology The University of Notre Dame Australia, Fremantle, Western Australia 2002 Contents Abstract................................................................................................................ iii Declaration of Authorship ................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements.............................................................................................. v Introduction.......................................................................................................... 1 1 Moltmann in Context: Biographical and Methodological Issues................... 9 Biographical Issues ..................................................................................... 10 Contextual Issues ........................................................................................ 13 Theological Method .................................................................................... 15 2 The Trinity and The Crucified God................................................................ 23 The Tradition............................................................................................... 25 Divine Suffering.......................................................................................... 29 The Rise of a ‘New Orthodoxy’................................................................. -

Introduction to the Sacraments * There Are Three Elements in the Concept of a Sacrament: 1

Introduction to the Sacraments * There are three elements in the concept of a sacrament: 1. The external- a sensibly perceptible sign of sanctifying grace 2. Its institution by God 3. The actual conferring of grace * From the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1131)- Sacraments are efficacious signs of grace, instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Church, by which divine life is dispensed to us”. “Efficacious signs of grace” (CCC 1127, 1145-1152)- Efficacious means that something is successful in producing a desired or intended result; it’s effective. Sacraments are accompanied by special signs or symbols that produce what they signify. These are the external, sensibly perceptible signs. “..instituted by Christ” (CCC 1117) -no human power could attach an inward grace to an outward sign, only God could do that. During his public ministry, Jesus fashioned seven sacraments. The Church cannot institute new sacraments. There can never be more or less than 7. In the coming weeks as we look at each of the sacraments individually, you’ll learn about how Christ instituted each one. “… entrusted to the Church” (CCC 1118) – By Christ’s will, the Church oversees the celebration of the sacraments. “…divine life is dispensed to us” – This divine life is grace, it is a share in God’s own life. The sacraments give sanctifying grace which is the sharing in God’s own life that is the result of God’s love, the Holy Spirit, indwelling in the soul. Sanctifying grace is not the only grace God wants to give us. Each sacrament also gives the sacramental grace of that particular sacrament. -

Getting Back to Idolatry Critique: Kingdom, Kin-Dom, and the Triune

86 87 Getting Back to Idolatry Critique: Kingdom, Critical theory’s concept of ideology is helpful, but when it flattens the idolatry critique by identifying idolatry as ideology, and thus making them synonymous, Kin-dom, and the Triune Gift Economy ideology ultimately replaces idolatry.4 I suspect that ideology here passes for dif- fering positions within sheer immanence, and therefore unable to produce a “rival David Horstkoetter universality” to global capitalism.5 Therefore I worry that the political future will be a facade of sheer immanence dictating action read as competing ideologies— philosophical positions without roots—under the universal market.6 Ideology is thus made subject to the market’s antibodies, resulting in the market commodi- Liberation theology has largely ceased to develop critiques of idolatry, espe- fying ideology. The charge of idolatry, however, is rooted in transcendence (and cially in the United States. I will argue that the critique is still viable in Christian immanence), which is at the very least a rival universality to global capitalism; the theology and promising for the future of liberation theology, by way of reformu- critique of idolatry assumes divine transcendence and that the incarnational, con- lating Ada María Isasi-Díaz’s framework of kin-dom within the triune economy. structive project of divine salvation is the map for concrete, historical work, both Ultimately this will mean reconsidering our understanding of and commitment to constructive and critical. This is why, when ideology is the primary, hermeneutical divinity and each other—in a word, faith.1 category, I find it rather thin, unconvincing, and unable to go as far as theology.7 The idea to move liberation theology from theology to other disciplines Also, although sociological work is necessary, I am not sure that it is primary for drives discussion in liberation theology circles, especially in the US, as we talk realizing divine work in history. -

The Synod Process

The Synod Process I Convocation and Preparation of the Synod 2 Preparatory Commission 1 The bishop convenes the synod with the consultation of the • Members of the preparatory commission are chosen by the bishop. Presbyteral Council. • The preparatory commission assists the bishop in organizing and preparing for the synod. • The bishop establishes a synodal secretariat and possibly a press office. 1 2 4 Preparatory phases of synod • Spiritual, catechetical and formational preparation 4 1. All are invited to pray for the ongoing intention of the synod and its results, that it might become an authentic 3 event of grace for the Church. 3 Publication of the Synodal 2. All should be informed on the nature and Directory purpose of the synod and the scope of its The Synodal Directory includes: deliberations. 1. composition of the synod; • Diocesan Consultation 2. norms by which elections of synodal members are to be conducted; 1. The faithful and the clergy of the Diocese 3. various offices to be exercised by the synod; are encouraged to express their needs, 4. procedural norms of the synod meetings. desires, challenges and opinions regarding the synod topics. 2. Meetings will take place at each parish, then deanery, to discuss synod topics. II Conducting the Synod • Determining the questions 1. The bishop determines the • The actual synod consists of the synodal sessions, questions on which the synodal typically in the cathedral. debate will concentrate. • Members of the synod make the profession of the faith before commencing synodal discussions. • Themes to be examined are introduced from a brief report; discussion begins. -

The Person of the Holy Spirit

The WORK of the Holy Spirit David J. Engelsma Herman Hanko Published by the British Reformed Fellowship, 2010 www.britishreformedfellowship.org.uk Printed in Muskegon, MI, USA Scripture quotations are taken from the Authorized (King James) Version Quotations from the ecumenical creeds, the Three Forms of Unity (except for the Rejection of Errors sections of the Canons of Dordt) and the Westminster Confession are taken from Philip Schaff, The Creeds of Christendom, 3 vols. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1966) Distributed by: Covenant Protestant Reformed Church 7 Lislunnan Road, Kells Ballymena, N. Ireland BT42 3NR Phone: (028) 25 891851 Website: www.cprc.co.uk E-mail: [email protected] South Holland Protestant Reformed Church 1777 East Richton Road Crete, IL 60417 USA Phone: (708) 333-1314 Website: www.southhollandprc.org E-mail: [email protected] Faith Protestant Reformed Church 7194 20th Avenue Jenison, MI 49418 USA Phone: (616) 457-5848 Website: www.faithprc.org Email: [email protected] Contents Foreword v PART I Chapter 1: The Person of the Holy Spirit 1 Chapter 2: The Outpouring of the Holy Spirit 27 Chapter 3: The Holy Spirit and the Covenant of Grace 41 Chapter 4: The Spirit as the Spirit of Truth 69 Chapter 5: The Holy Spirit and Assurance 84 Chapter 6: The Holy Spirit and the Church 131 PART II Chapter 7: The Out-Flowing Spirit of Jesus 147 Chapter 8: The Bride’s Prayer for the Bridegroom’s Coming 161 APPENDIX About the British Reformed Fellowship 174 iii Foreword “My Father worketh hitherto, and I work,” Jesus once declared to the unbelieving Jews at a feast in Jerusalem ( John 5:17).