1 Do Justice: Linking Christian Faith and Modern Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Theology in an Age of World Christianity

Public Theology in an Age of World Christianity 9780230102682_01_previii.indd i 2/11/2010 11:31:56 AM This page intentionally left blank Public Theology in an Age of World Christianity God’s Mission as Word-Event Paul S. Chung 9780230102682_01_previii.indd iii 2/11/2010 11:31:57 AM PUBLIC THEOLOGY IN AN AGE OF WORLD CHRISTIANITY Copyright © Paul S. Chung, 2010. All rights reserved. First published in 2010 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN: 978–0–230–10268–2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chung, Paul S., 1958– Public theology in an age of world Christianity : God's mission as word-event / Paul S. Chung. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–230–10268–2 (alk. paper) 1. Missions—Theory. I. Title. BV2063.C495 2010 266.001—dc22 2009039957 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. First edition: April 2010 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America. -

A Study on Religious Variables Influencing GDP Growth Over Countries

Religion and Economic Development - A study on Religious variables influencing GDP growth over countries Wonsub Eum * University of California, Berkeley Thesis Advisor: Professor Jeremy Magruder April 29, 2011 * I would like to thank Professor Jeremy Magruder for his valuable advice and guidance throughout the paper. I would also like to thank Professor Roger Craine, Professor Sofia Villas-Boas, and Professor Minjung Park for their advice on this research. Any error or mistake is my own. Abstract Religion is a popular topic to be considered as one of the major factors that affect people’s lifestyles. However, religion is one of the social factors that most economists are very careful in stating a connection with economic variables. Among few researchers who are keen to find how religions influence the economic growth, Barro had several publications with individual religious activities or beliefs and Montalvo and Reynal-Querol on religious diversity. In this paper, I challenge their studies by using more recent data, and test whether their arguments hold still for different data over time. In the first part of the paper, I first write down a simple macroeconomics equation from Mankiw, Romer, and Weil (1992) that explains GDP growth with several classical variables. I test Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2003)’s variables – religious fragmentation and religious polarization – and look at them in their continents. Also, I test whether monthly attendance, beliefs in hell/heaven influence GDP growth, which Barro and McCleary (2003) used. My results demonstrate that the results from Barro’s paper that show a significant correlation between economic growth and religious activities or beliefs may not hold constant for different time period. -

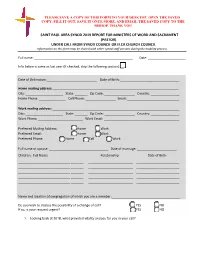

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

Public Theology the Spirit Sent to Bring Good News

CHAPTER 22 Public Theology The Spirit Sent to Bring Good News JASON S. SEXTON ll theology happens in particular with such uniformity are going to bring addi- contexts. This means that theol- tional perspectives beyond thinking with an Aogy, if worth doing at all—whether explicit precommitment “from and in the as critical construction, ecclesial dogma, or Spirit.” Some of these perspectives will reflect apologetic versions—is done in and from various sensibilities, proclivities, and eccen- real places. The contributions in the pres- tricities of authors, whether this be the result ent volume, including this chapter, have as of their ecclesial identities, some other theo- their stated perspective to be “thinking theo- logical or philosophical persuasions, or the logically from and in the Spirit.”1 While this part of the world they come from, their so- viewpoint, seen in each essay, contributes to called contexts.2 To refer to such a theology as the budding of what is being called Third Article Theology, even theologies beginning 2. For a recent example of an approach to devel- oping a regional theology, see Fred Sanders and Jason S. Sexton, eds., Theology and California: Theo- 1. Myk Habets, “Prologeomenon: On Starting logical Refractions on California’s Culture (New York: with the Spirit,” chapter 1 of the present volume. Routledge, 2014). 421 422 THIRD ARTICLE THEOLOGY contextual theology would be jejune, since all The Nature of Public Theology theology is done from somewhere and bears particular markings descriptive of particular Various models have been given in the extant settings and situations. literature attempting to describe precisely 4 These considerations bring the theolo- the meaning of the term “public theology.” I do not propose to settle any matters pertinent gian paying attention to the place where she finds an echo of the very first question asked 4. -

The Concept of Energy in T. F. Torrance and in Orthodox Theology

THE CONCEPT OF ENERGY IN T. F. TORRANCE AND IN ORTHODOX THEOLOGY Stoyan Tanev, PhD Associate Professor, Department of Technology & Innovation, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Theology, nieity o Sof lgi Co-founder, International Center for Theologicl Scientifc lte [email protected] Abstract: The motivation for this paper is fourfold: (1) to emphasize the fact that the teaching on the distinction between Divine essence and energies is an integral part of Orthodox theology; (2) to provide an analysis of why Torrance did not adhere to it; (3) to correct certain erroneous perceptions regarding Orthodox theology put forward by scholars who have already discussed Torrance’s view on the essence-energies distinction in its relation to eication or theosis an nall to suggest an analsis emonstrating the correlation between Torrance’s engagements with particular themes in modern physics and the content of his theological positions. This last analsis is mae comparing his scientic theological approach to the approach of Christos Yannaras. The comparison provides an opportunity to emonstrate the correlation etween their preoccupations with specic themes in moern phsics an their specic theological insights. Thomas Torrance has clearly neglected the epistemological insights emerging from the advances of quantum mechanics in the 20th century and has ended up neglecting the value of the Orthodox teaching on the distinction between Divine essence and energies. This neglect seems to be associated with his specic prehalceonian unerstaning of personprosoponhpostasis. s a result he has expressed opinions that contradict the apophatic character of the distinction between Divine essence and energies and the subtlety of the apophatic realism of iinehuman communion. -

The Synod Process

The Synod Process I Convocation and Preparation of the Synod 2 Preparatory Commission 1 The bishop convenes the synod with the consultation of the • Members of the preparatory commission are chosen by the bishop. Presbyteral Council. • The preparatory commission assists the bishop in organizing and preparing for the synod. • The bishop establishes a synodal secretariat and possibly a press office. 1 2 4 Preparatory phases of synod • Spiritual, catechetical and formational preparation 4 1. All are invited to pray for the ongoing intention of the synod and its results, that it might become an authentic 3 event of grace for the Church. 3 Publication of the Synodal 2. All should be informed on the nature and Directory purpose of the synod and the scope of its The Synodal Directory includes: deliberations. 1. composition of the synod; • Diocesan Consultation 2. norms by which elections of synodal members are to be conducted; 1. The faithful and the clergy of the Diocese 3. various offices to be exercised by the synod; are encouraged to express their needs, 4. procedural norms of the synod meetings. desires, challenges and opinions regarding the synod topics. 2. Meetings will take place at each parish, then deanery, to discuss synod topics. II Conducting the Synod • Determining the questions 1. The bishop determines the • The actual synod consists of the synodal sessions, questions on which the synodal typically in the cathedral. debate will concentrate. • Members of the synod make the profession of the faith before commencing synodal discussions. • Themes to be examined are introduced from a brief report; discussion begins. -

Public Theology in the Face of Pain and Suffering: a Proletarian Perspective Florence Juma

Consensus Volume 36 Article 6 Issue 2 Public Theology 11-25-2015 Public Theology in the face of pain and suffering: A proletarian perspective Florence Juma Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Juma, Florence (2015) "Public Theology in the face of pain and suffering: A proletarian perspective," Consensus: Vol. 36 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol36/iss2/6 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Consensus by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Juma: Public Theology in the face of pain and suffering Public Theology in the face of pain and suffering: A proletarian perspective Florence Juma* Introduction basic understanding of theology is the quest for knowledge of the Divine—the study of God.1 But why, one may ask, undertake such an endeavour, and to what end? My A simple response would be, to know God is to enhance and enrich my life and service. To know God is to understand His creation – humanity and, the created context. I practice theology to learn more about God and His creation. In the process, that knowledge serves to improve my professional practice as a spiritual care provider in a public health institution. Thus, originates the burden of this task – the implication of doing theology in a public domain. My hope is to reflect on the implications of my professional practice as a spiritual care provider engaging in theological discourse in a public health institution. -

The Synod for the Amazon

THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON Marcelo Barros • The divine revelation that arrives late1 • ABSTRACT It is good news that the Synod of Catholic Bishops from around the world, convened by Pope Francis and which will take place in October in Rome, has been prepared with extensive consultation with Amazonian communities and civil organizations working with them. The novelty of this Synod is the call for the Church, instead of acting as a teacher, to listen and hear the voice of the Amazon. In doing so, the Church will discover how to confront the challenges and new possibilities for its mission; a new vision and in opposition to the colonization in which it was complicit. KEYWORDS Spiritual listening | Catholic Church | Earth cry | Amazon peoples | Walk together • SUR 29 - v.16 n.29 • 133 - 138 | 2019 133 THE SYNOD FOR THE AMAZON There is no doubt that for the peoples of the Amazon, the news that Pope Francis convoked a Synod of Roman-Catholic Bishops from around the world to reflect about the appeals that the Amazon is making to the Universal Church (the body of Christian churches worldwide) was well-received. As Dom Roque Paloschi, president of the Indigenist Missionary Council in Brazil (Conselho Indigenista Missionário - CIMI), affirmed, “the Synod for the Amazon practically began in January of 2018, in Puerto Maldonado (Peru), during the Pope’s meeting with Amazonian people.”2 The Synod of Bishops is an institution that continues an old church custom and enacts the Church’s vocation as a sign and instrument of unity for all of humanity. -

1 Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent Christians Believe That The

Trinity, Filioque and Semantic Ascent1 Christians believe that the Persons of the Trinity are distinct but in every respect equal. We believe also that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father. It is difficult to reconcile claims about the Father’s role as the progenitor of Trinitarian Persons with commitment to the equality of the persons, a problem that is especially acute for Social Trinitarians. I propose a metatheological account of the doctrine of the Trinity that facilitates the reconciliation of these two claims. On the proposed account, “Father” is systematically ambiguous. Within economic contexts, those which characterize God’s relation to the world, “Father” refers to the First Person of the Trinity; within theological contexts, which purport to describe intra-Trinitarian relations, it refers to the Trinity in toto-- thus in holding that the Son and Holy Spirit proceed from the Father we affirm that the Trinity is the source and unifying principle of Trinitarian Persons. While this account solves a nagging problem for Social Trinitarians it is theologically minimalist to the extent that it is compatible with both Social Trinitarianism and Latin Trinitarianism, and with heterodox Modalist and Tri-theist doctrines as well. Its only theological cost is incompatibility with the Filioque Clause, the doctrine that the Holy Spirit proceeds from both the Father and the Son—and arguably that may be a benefit. 1. Problem: the equality of Persons and asymmetry of processions In addition to the usual logical worries about apparent violations of transitivity of identity, the doctrine of the Trinity poses theological problems because it commits us to holding that there are asymmetrical quasi-causal relations amongst the Persons: the Father “begets” the Son and “spirates” the Holy Spirit. -

Synodality” – Results and Challenges of the Theological Dialogue Between the Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church

“SYNODALITY” – RESULTS AND CHALLENGES OF THE THEOLOGICAL DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH Archbishop Job of Telmessos I. The results of the Joint International Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church The Joint International Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church has been focusing on the topic of “Primacy and Synodality” over the last twelve years. This is not surprising, since the issue of the exercise of papal primacy has been an object of disagreement between Orthodox and Catholics over a millennium. The Orthodox contribution has been to point out that primacy and synodality are both inseparable: there cannot be a gathering (synodos) without a president (protos), and no one cannot be first (protos) if there is no gathering (synodos). As the Metropolitan of Pergamon, John Zizioulas, pointed out: “The logic of synodality leads to primacy”, since “synods without primates never existed in the Orthodox Church, and this indicates clearly that if synodality is an ecclesiological, that is, dogmatical, necessity so must primacy [be]”1. The Ravenna Document (2007) The document of the Joint International Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church, referred as the “Ravenna Document” (2007), speaks of synodality and conciliarity as synonyms, “as signifying that each member of the Body of Christ, by virtue of baptism, has his or her place and proper responsibility in eucharistic koinonia (communio in Latin)”. It then affirms that “conciliarity reflects the Trinitarian mystery and finds therein its ultimate foundation”2 and from there, considers that “the Eucharist manifests the Trinitarian koinônia actualized in the faithful as an organic unity of several members each of whom has a charism, a service or a proper ministry, necessary in their variety and diversity for the edification of all in the one ecclesial Body of Christ”3. -

Summary History of the Synod of the West

Summary History of the Synod of the West By Joseph L. Mihelic, and Lightly edited by Joel L. Samuels Introduction German Presbyterianism in the Upper Mississippi Valley may be said to have begun with the coming of the Rev. and Mrs. Peter Flury to Dubuque, Iowa in the fall of 1846. Peter Flury was a Swiss-German and his wife Sophie Jackson Flury was English from Brighton, England. After serving a pastorate in Schiers, Switzerland, Pastor Flury and his wife decided to come to America as missionaries to American Indians, and applied to the American Mission Board for an assignment. The Board, however, commissioned him in October 1846 and sent him to Dubuque, Iowa where there was a colony of Swiss-German immigrants who had asked the American Mission Board for a pastor. The Flurys came to Dubuque in the fall of 1846 and rented a house in which they began a school for the children and adults of the Swiss immigrants, as well as anyone who was interested in learning German and English and the Christian religion. The school was free and open to Protestants and Roman Catholics. On Christmas Day of 1847, Flury organized a congregation of thirty-five charter members and called this congregation the German Evangelical Church. He provided it also with a Constitution which he modeled after the Reform Church of Switzerland, the Church which he served at Schiers, Switzerland. This constitution has been preserved in the Kirchenbuch (“church-book”) of the congregation and shows Flurys’ concern for the correct order in the operation of the congregation's business, as well as his interest in education of both children and adults. -

A Review of Dissident Sacramental Theology

A REVIEW OF DISSIDENT SACRAMENTAL THEOLOGY Five years ago it was my privilege to address this Society, making a cursory review of the main points on which Catholics and Orthodox disagree in the realm of dogmatic theology. These points are neither too numerous nor too difficult to preclude a harmonious solution. The most fundamental issue is the primacy of the pope. But even here, since the Orthodox already believe in the infallibility of the Church and in an honorary primacy of the Bishop of Rome in that Church, it might not be too sanguine to posit the possibility of arriving at an understanding of the pope as the mouthpiece of the infallible Church. This year the officers of the Society have requested a review of Orthodox sacramental practice in the hope that this might furnish some summary of Orthodox moral theology by providing a glimpse of the actual religious life in an Orthodox parish, as well as bring- ing our Catholic theologians up to date on the practical questions they must face regarding intercommunion if any reunion should ever be achieved. At the outset we should express the caution that in this practical as well as in the theoretical sphere, we must beware of absolute predications—because there is apt to be a divergency of practice between the various national groups of Orthodox and even within the same national group. The chief bodies of Orthodox—at least as far as theological leadership is concerned—are the Greeks and the Russians. Usually the Syrian and Albanian Orthodox will follow Greek practice, while the various Slav groups like the Serbs, Bulgars and Ukrainians will be content to follow the hegemony of the Russian Orthodox Church.