Concordia Theological Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice of God in Damnation

THE JUSTICE OF GOD IN THE DAMNATION OF SINNERS “That every mouth may be stopped” (Romans 3:19). By Jonathan Edwards Online Edition by: International Outreach, Inc. PO Box 1286, Ames, Iowa 50014 (515) 292-9594 THE JUSTICE OF GOD IN THE DAMNATION OF SINNERS By Jonathan Edwards "That every mouth may be stopped." (Romans 3:19) The main subject of the doctrinal part of this epistle, is the free grace of God in the salvation of men by Christ Jesus; especially as it appears in the doctrine of justification by faith alone. And the more clearly to evince this doctrine, and show the reason of it, the apostle, in the first place, establishes that point, that no flesh living can be justified by the deeds of the law. And to prove it, he is very large and particular in showing, that all mankind, not only the Gentiles, but Jews, are under sin, and so under the condemnation of the law; which is what he insists upon from the beginning of the epistle to this place. He first begins with the Gentiles; and in the first chapter shows that they are under sin, by setting forth the exceeding corruptions and horrid wickedness that overspread the Gentile world: and then through the second chapter, and the former part of this third chapter, to the text and following verse, he shows the same of the Jews, that they also are in the same circumstances with the Gentiles in this regard. They had a high thought of themselves, because they were God's covenant people, and circumcised, and the children of Abraham. -

Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained a Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D

Welcome to OUR 4th VIRTUAL GSP class. Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained A Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D. Lord Jesus Christ, may our church be a temple of your presence and a house of prayer. Be always near us when we seek you in this place. Draw us to you, when we come alone and when we come with others, to find comfort and wisdom, to be supported and strengthened, to rejoice and give thanks. May it be here, Lord Christ, that we are made one with you and with one another, so that our lives are sustained and sanctified for your service. Amen. HISTORY OF CHURCH BUILDINGS The Bible's authors never thought of the church as a building. To early Christians the word “church” referred to the act of assembling together rather than to the building itself. As long as the Roman government did not did not recognize and protect Christian places of worship, Christians of the first centuries met in Jewish places of worship, in privately owned houses, at grave sites of saints and loved ones, and even outdoors. In Rome, there are indications that early Christians met in other public spaces such as warehouses or apartment buildings. The domus ecclesiae or house church was a large private house--not just the home of an extended family, its slaves, and employees--but also the household’s place of business. Such a house could accommodate congregations of about 100-150 people. 3rd-century house church in Dura-Europos, in what is now Syria CHURCH BUILDINGS In the second half of the 3rd century, Christians began to construct their first halls for worship (aula ecclesiae). -

Purgatory--Purification After Death by Fire Heb. 12:29

Purgatory--Purification After Death By Fire Heb. 12:29 - God is a consuming fire (of love in heaven, of purgation in purgatory, or of suffering and damnation in hell). 1 Cor. 3:10-15 - works are judged after death and tested by fire. Some works are lost, but the person is still saved. Paul is referring to the state of purgation called purgatory. The venial sins (bad works) that were committed are burned up after death, but the person is still brought to salvation. This state after death cannot be heaven (no one with venial sins is present) or hell (there is no forgiveness and salvation). 1 Cor. 3:15 – “if any man’s work is burned up, he will suffer loss, though he himself will be saved, but only as through fire.” The phrase for "suffer loss" in the Greek is "zemiothesetai." The root word is "zemioo" which also refers to punishment. The construction “zemiothesetai” is used in Ex. 21:22 and Prov. 19:19 which refers to punishment (from the Hebrew “anash” meaning “punish” or “penalty”). Hence, this verse proves that there is an expiation of temporal punishment after our death, but the person is still saved. This cannot mean heaven (there is no punishment in heaven) and this cannot mean hell (the possibility of expiation no longer exists and the person is not saved). 1 Cor. 3:15 – further, Paul writes “he himself will be saved, "but only" (or “yet so”) as through fire.” “He will be saved” in the Greek is “sothesetai” (which means eternal salvation). -

Chapter 2 Orthodox Church Life A. Church Etiquette an Orthodox

chapter 2 Orthodox Church Life A. Church Etiquette The Church is the earthly heaven in which the heavenly God dwells and moves. An Orthodox Church is that part of God’s creation which has been set apart and “reclaimed” for the Kingdom of God. Within its walls, the heavenly and earthly realms meet, outside time, in the acts of worship and Sacrifice offered there to God. Angels assist the Priest during the Divine Liturgy, and Saints and members of the Church Triumphant participate in the Ser- vices. The Blessed Theotokos, the Mother of God, is also present and, of course, our Lord Jesus Christ is invisibly present wher- ever two or three gather in His Name, just as He is always present in the reserved Eucharist preserved on the Holy Table of most Orthodox Churches. Given these very significant spiritual realities, we should al- ways approach an Orthodox Church with the deepest attitude of reverence. Even when passing an Orthodox Church on foot or in a car, we always cross ourselves out of respect for the presence of God therein. It is, indeed, unthinkable that we should ever pass in front of an Orthodox Church without showing such rev- erence. Therefore, it is obvious that we must approach our meeting with the heavenly realm during Divine Services with careful and proper preparation. When preparing for Church, we should always dress as we would for a visit to an important dignitary. After all, we are about to enter into the very presence of God. Therefore, casual apparel is not appropriate. For example, shorts should never be St. -

Quality Silversmiths Since 1939. SPAIN

Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com - ARTIMETAL - PROCESSIONALIA 2014-2015 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN ARTISTIC SILVER INDEXINDEX Presentation ......................................................................................... Pag. 1-12 ARTISTIC SILVER - ARTIMETAL ARTISTICPresentation SILVER & ARTIMETAL Pag. 1-12 ChalicesChalices && CiboriaCiboria ........................................................................... Pag. 13-6713-52 MonstrancesCruet Sets & Ostensoria ...................................................... Pag. 68-7853 TabernaclesJug & Basin,........................................................................................... Buckets Pag. 79-9654 AltarMonstrances accessories & Ostensoria Pag. 55-63 &Professional Bishop’s appointments Crosses ......................................................... Pag. 97-12264 Tabernacles Pag. 65-80 PROCESIONALIAAltar accessories ............................................................................. Pag. 123-128 & Bishop’s appointments Pag. 81-99 General Information ...................................................................... Pag. 129-132 ARTIMETAL Chalices & Ciboria Pag. 101-115 Monstrances Pag. 116-117 Tabernacles Pag. 118-119 Altar accessories Pag. 120-124 PROCESIONALIA Pag. 125-130 General Information Pag. 131-134 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. Justo Dorado, 12 28040 Madrid, Spain Product design: Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. CHALICES & CIBORIA Our silversmiths combine -

44-How Can Ye Escape the Damnation of Hell?

More About Jesus #44 (9/25/16) Bible Bap3st Church, Port Orchard, WA — Dr. Al Hughes “How Can Ye Escape the Damnation of Hell?” Matthew 23:33 Matthew 23 is one of the least preached passages in the New Testa- ment. It would be classified as “hate literature” by the media today. This was the last public sermon Jesus preached before He was arrested and delivered up to be crucified. The setting is the Temple in Jerusalem (21:23 cf. 24:1). This scathing sermon is filled with warnings of judgment, woes upon hypocrisy, and dripping with sarcasm. Nothing like this would ever be preached in Joel Osteen’s church. READ MATTHEW 23. It is no wonder that after Jesus finishes this sermon, the Pharisees plot to kill Him (26:1-4). It is fitting that the last message Jesus preached on earth would be cli- maxed with an admonition about hell (v. 33). Strong language similar to the preaching of John the Baptist (Mt. 3:7). I. The PREACHING on hell. Not much preaching on hell today. A. The PREACHER—Most of what we know about hell, we learn from the teaching of Jesus. He preached more about hell than He did heaven! Jesus was a “hell-fire and damnation” preacher. • Mt. 5:22–…in danger of hell fire. (from Sermon on the Mount) • Mt. 5:29–…thy whole body should be cast into hell... • Mt. 16:18–…the gates of hell… • Mt. 23:15–…the child of hell… • Mt. 23:33–…how can ye escape the damnation of hell? • Mk. -

Altar Server Instructions Booklet

Christ the King Catholic Church ALTAR SERVER INSTRUCTIONS Revised May, 2012 - 1 - Table of Contents Overview – All Positions ................................................................................................................ 4 Pictures of Liturgical Items ............................................................................................................. 7 Definition of Terms: Liturgical Items Used At Mass ..................................................................... 8 Helpful Hints and Red Cassocks................................................................................................... 10 1st Server Instructions ................................................................................................................. 11 2nd Server Instructions ................................................................................................................ 14 Crucifer Instructions .................................................................................................................... 17 Special Notes about FUNERALS ................................................................................................ 19 BENEDICTION .......................................................................................................................... 23 - 2 - ALTAR SERVER INSTRUCTIONS Christ the King Church OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION First of all, THANK YOU for answering God’s call to assist at Mass. You are now one of the liturgical ministers, along with the priest, deacon, lector and Extraordinary -

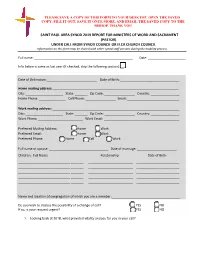

UNDER CALL from SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on This Form May Be Shared with Other Synod Staff Persons During the Mobility Process

PLEASE SAVE A COPY OF THIS FORM TO YOUR DESKTOP, OPEN THE SAVED COPY, FILL IT OUT, SAVE IT ONCE MORE, AND EMAIL THE SAVED COPY TO THE BISHOP. THANK YOU SAINT PAUL AREA SYNOD 2019 REPORT FOR MINISTERS OF WORD AND SACRAMENT (PASTOR) UNDER CALL FROM SYNOD COUNCIL OR ELCA CHURCH COUNCIL Information on this form may be shared with other synod staff persons during the mobility process Full name: _______________________________________________________ Date: _____________________ Info below is same as last year (if checked, skip the following section):__ Date of Ordination:____________________________ Date of Birth: _________________________________ Home mailing address: ______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Home Phone: _______________ Cell Phone: _________________ Email: _____________________________ Work mailing address: _______________________________________________________________________ City: _____________________ State: _______ Zip Code: _________________ Country: ________________ Work Phone: _________________________ Work Email: __________________________________________ Preferred Mailing Address: Home Work Preferred Email: Home Work Preferred Phone: Home Cell Work Full name of spouse: _________________________________ Date of marriage: ______________________ Children: Full Name Relationship Date of Birth _____________________________ _______ _________________________ ________________________ _____________________________ -

Occupational Limbo, Transitional Liminality and Permanent Liminality: New Conceptual Distinctions

Occupational limbo, transitional liminality and permanent liminality: New conceptual distinctions Matthew Bamber, Jacquelyn Allen-Collinson and John McCormack Abstract This article contributes new theoretical perspectives and empirical findings to the conceptualisation of occupational liminality. Here, we posit ‘occupational limbo’ as a state distinct from both transitional and permanent liminality; an important analytic distinction in better understanding occupational experiences. In its anthropological sense, liminality refers to a state of being betwixt and between; it is temporary and transitional. Permanent liminality refers to a state of being neither-this-nor-that, or both-this-and-that. We extend this framework in proposing a conceptualisation of occupational limbo as always-this-and-never- that, where this is less desirable than that. Based on interviews with 51 teaching-only staff at 20 research-intensive ‘Russell Group’ universities in the United Kingdom, the findings highlight some challenging occupational experiences. Interviewees reported feeling ‘locked- in’ to an uncomfortable state by a set of structural and social barriers often perceived as insurmountable. Teaching-only staff were found to engage in negative and often self- depreciatory identity talk that highlighted a felt inability to cross the līmen to the elevated status of ‘proper academics’. The research findings and the new conceptual framework provide analytic insights with wider application to other occupational spheres, and can thus enhance the understanding not just of teaching-only staff and academics, but also of other workers and managers. Keywords Academic careers, liminality, limbo organisational theory, work environment Introduction The purpose of this article is to analyse and extend current understandings of the concept of liminality, originally utilised in anthropology in relation to rites of passage (Van Gennep, 1960). -

Father God Explains the Souls in Purgatory's Anguish To

Behold, he cometh with the clouds, and every eye shall see him, and they also that pierced him. And all the tribes of the earth shall bewail themselves because of him. Even so. Amen. I am Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, saith the Lord God, who is, and who was, and who is to come, the Almighty. Revelation 1:7–8 Father God Explains the Souls in Purgatory’s Anguish to Contact Their Loved Ones and What They Need from Earth to Be Released into Heaven 08/03/2016 Father God, Jesus Christ and Mother Mary Thank you, my daughter, for sitting with me, your Father God, the Holy Spirit and Blessed Mother Mary. My little one, I, your Father God, I am here with you, sitting next to you. Oh, today you have been very occupied with many chores of your daily life. It was needed. Soon you are going to have a helping hand. I desire for you to be totally absorbed in the intimacy of our hearts − no other distractions. There is so much to be done. Today is very prognostic of many souls in need of coming to heaven. My little lamb, I, your Father, I am going to explain more profoundly about these souls coming to heaven. My little lamb, there are many souls waiting to be released with prayers, to come, to enter heaven. These souls are thirsty for their coming into heaven. There are many waiting for long, long years without relief from earth to heaven. My little one, I have told you before: Holy Mass is very essential as my people come to eternal life. -

Universal Salvation and the Problem of Hell John R

Theological Studies 52 (1991) CURRENT ESCHATOLOGY: UNIVERSAL SALVATION AND THE PROBLEM OF HELL JOHN R. SACHS, S.J. Weston School of Theology, Cambridge, Mass. HE PURPOSE of this article is to take a fresh look at the ancient and Tmuch misunderstood theme of apocatastasis. Increasing contempo rary use of the apocalyptic language of hell, hand in hand with the alarming appeal and growth of fundamentalism, sectarianism, and inte- gralism, suggest the urgency of this endeavor. After first surveying the checkered history of this theme from biblical times to the present, I will, second, state and describe the central points of current Catholic theology on these issues. It manifests a remarkable degree of consensus. Third, I shall turn more closely to the highly original thought of Hans Urs von Balthasar, whose approach seems most challenging. Fourth, I shall raise a question concerning the ability of human freedom to reject God defin itively. Finally, my conclusion will stress how a properly understood Christian universalism is not only consonant with several central strands of Christian belief, but is also profoundly relevant to the religious and cultural developments of the present age. THE DOCTRINE OF APOCATASTASIS The doctrine of apocatastasis, commonly attributed to Origen, main tained that the entire creation, including sinners, the damned, and the devil, would finally be restored to a condition of eternal happiness and salvation. This was an important theme in early Christian eschatology.1 Even before the Christian era, of course, the idea of an apokatastasis paritàri was well known in ancient religion and philosophy. In Eastern thought especially, one finds a predominantly cyclical conception of time and history according to which the end always involves a return to the 1 See, for example, Brian E. -

The Synod Process

The Synod Process I Convocation and Preparation of the Synod 2 Preparatory Commission 1 The bishop convenes the synod with the consultation of the • Members of the preparatory commission are chosen by the bishop. Presbyteral Council. • The preparatory commission assists the bishop in organizing and preparing for the synod. • The bishop establishes a synodal secretariat and possibly a press office. 1 2 4 Preparatory phases of synod • Spiritual, catechetical and formational preparation 4 1. All are invited to pray for the ongoing intention of the synod and its results, that it might become an authentic 3 event of grace for the Church. 3 Publication of the Synodal 2. All should be informed on the nature and Directory purpose of the synod and the scope of its The Synodal Directory includes: deliberations. 1. composition of the synod; • Diocesan Consultation 2. norms by which elections of synodal members are to be conducted; 1. The faithful and the clergy of the Diocese 3. various offices to be exercised by the synod; are encouraged to express their needs, 4. procedural norms of the synod meetings. desires, challenges and opinions regarding the synod topics. 2. Meetings will take place at each parish, then deanery, to discuss synod topics. II Conducting the Synod • Determining the questions 1. The bishop determines the • The actual synod consists of the synodal sessions, questions on which the synodal typically in the cathedral. debate will concentrate. • Members of the synod make the profession of the faith before commencing synodal discussions. • Themes to be examined are introduced from a brief report; discussion begins.