Iceland and the Crisis: Territory, Europe, Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Diplomacy the Icelandic Way

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCE Cultural Diplomacy The Icelandic Way The current state of Iceland’s cultural diplomacy practices Master Thesis in Cultural Management Student: Bergþóra Laxdal Advisor: Dr. Gregory Payne Fall – 2016 ABSTRACT This 30 ECT credit MA thesis is a case study that discusses the role of the Government of Iceland and the creative centers in Iceland when publicly funding cultural projects that take place internationally. The objective is to examine the current state of how the Government of Iceland conducts its cultural diplomacy practices. In examining the Government practices on this topic, the following three questions are pursued; is there an informal cultural diplomacy policy in place; what principles drive that policy and what strategic approach is in place to fulfill the policy? The participants were selected due to their expertise in the cultural affairs of Iceland, and were divided into two groups. The first group, the Expert Committee on Art and Culture Expert Committee on Art and Culture headed by Promote Iceland, was selected to identify the Government agencies from which the creative centers receive their public funding and to gain insight into how projects that receive public funding are selected to represent Iceland abroad. This group delivered their answers in a written open ended questionnaire. The second group, Government cultural representatives with responsibilities in distributing public funding, was selected to get an overview of how the distribution of funds takes place and delivered their answers through an interview. The results were analyzed according to theories about policy and policy streams and strategy processes. The results support the view of an informal cultural policy being in place. -

Icelandic Street Art. an Analysis of the Formation and Development. Dissertation Zur Erlangung Des Grades Eines Doktors Der Phil

Icelandic street art. An analysis of the formation and development. Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie an der Philosophischen Fakultät der Technischen Universität Dresden vorgelegt von Joanna Zofia Rose geb. am 29.06.1985 in Wroclaw Betreuer: Prof. Dr. Bruno Klein Institut für Kunst- und Musikwissenschaft der TU Dresden Verteidigung am 14.07.2020 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Bruno Klein 2. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Ilaria Hoppe Table of contents PART I ......................................................................................................................... 5 Theory .......................................................................................................................... 5 1. Methodology and research goals ............................................................................................... 6 1.1 Subject matter and research tools ....................................................................................... 6 1.2 Historical background reasoning the topic choice ............................................................. 10 1.3 Development of history of art as a discipline reasoning the topic choice ......................... 12 1.4 Information sources used in research, collection methods and value assessment ........... 14 1.5 Specifics of Iceland ............................................................................................................. 18 2. Fluctuating scope of the area of interest ................................................................................ -

Beauty and Threat: the Effect of the Icelandic Landscape on the Works of Icelandic Landscape Painters

Beauty and Threat: The Effect of the Icelandic Landscape on the Works of Icelandic Landscape Painters Terry Smith MacEwan University May 27, 2018 AGAD 230 Professor: Annetta Latham Dedication – With deep gratitude Table of contents This research project is dedicated to the living artists who so generously shared their insights Abstract 5 and their time: Hrafnhildur Inga Sigurðardóttir; Gudmunda Kristinsdóttir; Kristín Tryggvadíttir; Introduction 7 Bjarni Sigurbjörnsson; and art critic Hannes Sigurdsson. I would be remiss not to thank my The geography of beauty and threat 11 cousins and their partners, who shuttled me, fed me, and who personally invested in the The history of landscape in Icelandic art 17 work I was doing, giving insight and context to Icelandic art, history, society and ultimately, Jóhannes Sveinsson Kjarval 25 enriching the research and the experience: Gunnar Gunnarsson and Jódís Hlöðversdóttir; Georg Guðni Hauksson 33 Bjartur Logi Fránn Gunnarsson and Mirra Sjöfn; Anna Jóhannsdóttir and Emil Ragnar Hrafnhildur Inga Sigurðardóttir 45 Hjartarson; Sigríður Anna Emilsdóttir; Guðrún Ragna Emilsdóttir; and Guðrún Fjeldsted. Guðmunda Kristinsdóttir 49 Bjarni Sigurbjörnsson 57 Conclusion 63 Bibliography 68 Cover image: Fig. 15. To illustrate the volatility of the weather in Iceland, five minutes before and after this picture was taken, it was a gloriously sunny day on the south coast at Vík, Iceland. Over the course of the two hours I spent in this community, this scene repeated itself three times. Terry Smith 2018, jpg. 2 Beauty and Threat: The Effect of the Icelandic Landscape on the Works of Icelandic Landscape Painters Beauty and Threat: The Effect of the Icelandic Landscape on the Works of Icelandic Landscape Painters 3 Abstract This research paper explores the subject of topophilia – a strong sense of place – as it relates to the effects of geography, environment and social influences on the works of Icelandic painters. -

Of Horses and Men Symbolic Value of Horses in Icelandic Art

FILM/SZTUKA/MEDIA „Zoophilologica. Polish Journal of Animal Studies” Nr 6/2020 Mity – stereotypy – uprzedzenia issn 2451-3849 DOI: http://doi.org/10.31261/ZOOPHILOLOGICA.2020.06.25 Emiliana Konopka http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4527-2689 University of Gdańsk Faculty of Arts Of Horses and Men Symbolic Value of Horses in Icelandic Art O koniach i ludziach. Symboliczne О лошадях и людях. Символическое znaczenie konia w sztuce islandzkiej значение лошади в исландском искусстве Abstrakt Абстракт Konie stanowią jeden z najpopularniejszych Изображение лошадей является одной из tematów w sztuce islandzkiej. Figura konia самых популярных тем в исландском ис- islandzkiego (Icelandera) może być intepre- кусстве. Образ исландской лошади можно towana jako część tożsamości narodowej интерпретировать как элемент националь- Islandczyków: od czasów osiedlenia Islandii, ного самосознания исландцев: начиная konie były obecne podczas budowania pań- с времен заселения Исландии лошади stwa oraz tworzenia narodu. Stąd poniższy участвовали в строительстве государства tekst przedstawia symboliczne znaczenie ko- и формировании общества. В статье автор nia w Islandii poprzez przyjrzenie się dwóm иллюстрирует символическое значения ло- strefom: sacrum (wierzenia oraz mitologia шади в Исландии, ссылаясь на две сферы: nordycka) i profanum (praca, życie codzien- священную (верования и скандинавская ne). Motyw konia rozpatrywany jest tutaj мифология) и светскую (труд, повседнев- zarówno w tradycyjnych przedstawieniach ная жизнь). Мотив лошади рассматрива- (w sztuce i literaturze), jak również we współ- ется как в традиционных представлениях czesnej narracji sztuk wizualnych (malarstwa (искусство и литература), так и в современ- i filmu). Wywód oparty jest na (ko)relacji ko- ном повествовании изобразительного ис- nia i człowieka w Islandii, ze szczególnym кусства (живопись и кино). -

Grapevine 2021 08.Pdf

Issue 07 2021 www.gpv.is Þór or Thor? Deportations Frin"e Festival Pettin" Belu"as First: There can be only one, News: Is it even le!al to send Art: The lockdown's over, and Travel: They're really cute, and Marvel's ain't it people to Greece? Reykjavík's best is back and super friendly! Back Into The Deep End Fannar Ingi Friðþjófsson, now the sole member of indie dream pop outfit Hipsumhaps, comes out of quarantine to face his most challenging year yet COVER ART: are known for their Photographer: brilliant lyrics and unique Svavar Pétur Eysteinsson sense of humour. a.k.a. Prins Póló The photo was shot at the In cooperation with our pool in Álftanes, which cover star, Hipsumhaps, let us visit early in the we asked the legendary morning to take them. We Prins Póló to do the are forever grateful for photoshoot. The reason their wonderful staff and was simple: Both artists patient guests! 08: Illegal Deporations 12-13: FRINGE IT UP! 31: We Met Whales <3 06: It's Always 4:20 14: Cheer Up, Girl 18: Amiina & The Love Of Somewhere 20: A Gallery In A Gas Lighthouses First 08: Thor Vs. Þór Station... What?! 23: Vaccination Nation EDITORIAL The Pandemic Is O"cially Over In Iceland, The Public Won Iceland has officially declared victory Icelanders are now looking toward the future. The over the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has been hard and we need to rebuild. The sooner, Icelandic Government decided to the better. Cultural life is slowly restoring itself and unem- completely relax domestic restric- ployment numbers are lowering every day. -

Some Heroic Motifs in Icelandic Art. Scripta Islandica 68/2017

SCRIPTA ISLANDICA ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK 68/2017 REDIGERAD AV LASSE MÅRTENSSON OCH VETURLIÐI ÓSKARSSON under medverkan av Pernille Hermann (Århus) Else Mundal (Bergen) Guðrún Nordal (Reykjavík) Heimir Pálsson (Uppsala) Henrik Williams (Uppsala) UPPSALA, SWEDEN Publicerad med stöd från Vetenskapsrådet. © 2017 respektive författare (CC BY) ISSN 0582-3234 EISSN 2001-9416 Sättning: Ord och sats Marco Bianchi urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-336099 http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-336099 Innehåll LARS-ERIK EDLUND, Ingegerd Fries (1921–2016). Minnesord ...... 5 AÐALHEIÐUR GUÐMUNDSDÓTTIR, Some Heroic Motifs in Icelandic Art 11 DANIEL SÄVBORG, Blot-Sven: En källundersökning .............. 51 DECLAN TAGGART, All the Mountains Shake: Seismic and Volcanic Imagery in the Old Norse Literature of Þórr ................. 99 ELÍN BÁRA MAGNÚSDÓTTIR, Forfatterintrusjon i Grettis saga og paralleller i Sturlas verker ............................... 123 HAUKUR ÞORGEIRSSON & TERESA DRÖFN NJARÐVÍK, The Last Eddas on Vellum .............................................. 153 HEIMIR PÁLSSON, Reflections on the Creation of Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda ........................................... 189 MAGNUS KÄLLSTRÖM, Monumenta lapidum aliquot runicorum: Om runstensbilagan i Verelius’ Gothrici & Rolfi Westrogothiae Regum Historia (1664) ................................. 233 MATTEO TARSI, Creating a Norm for the Vernacular: Some Critical Notes on Icelandic and Italian in the Middle Ages ............ 253 OLOF SUNDQVIST, Blod och blót: Blodets betydelse och funktion -

Iceland Times

Description of more than 300 places all around Iceland With High-quality photos and maps With Contact information and QR-code to use with your smartphone With Colour-coded sections for easy reference and reading Additional online content and updates at ISBN 978-9979-72-292-2 www.icelandictimes.com Iceland celandic Times Extra is an extensive and informative book about the Icelandic Tourist Industry. It contains articles from the first 16 issues of Icelandic Times magazine as well as a number of brand new articles onI nature, natural wonders, birds and wildlife, towns and villages, museums and galleries, swimming pools, activities, curiosities, accommodation, restaurants, design and handicraft – and the endless exciting possibilities available to our guests. The winter wonders with the Nordic Lights, the summer season with the Midnight Sun. Whether it is fising, sailing, horse-riding, skiing, snow-mobiling, adventure tours, hiking, mountaineering, river-rafting, glacier-tours, hang-gliding, or just plain relaxation in the tranquil nature, here you will find the best possibilities on offer in Iceland. The book travels clock-wise around Iceland, starting in Reykjavík – at 08.00 – with maps for villages and towns, as well as greater areas. There is vast information on each of the ten main areas, their specialities and interest points; Reykjavík, West Coast, Westfjords, North-West, North-East, East, South-East, South, South-West and, of course, the Highlands. The tourist industry is an ever-growing field and thus we do not claim to give a complete account of the possibilities – but we are close. You can be pretty sure you‘ll fid everything you need in this book. -

A Finding Aid to the American Federation of Arts Records, 1895-1993 (Bulk 1909-1969), in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the American Federation of Arts Records, 1895-1993 (bulk 1909-1969), in the Archives of American Art Wendy Bruton and Barbara D. Aikens 2000 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 5 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 7 Appendix: List of Artists Exhibiting with American Federation of Arts............................. 7 Names and Subjects .................................................................................................. 127 Container Listing ......................................................................................................... 132 Series 1: Board of Trustees, circa 1895-1968..................................................... 132 Series 2: Administrative Records, 1910-1966...................................................... 134 Series 3: Special Programs, 1950-1967............................................................. -

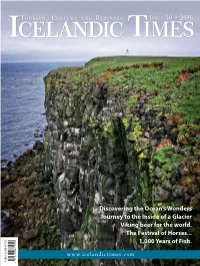

Discovering the Ocean's Wonders Journey to the Inside of a Glacier

ISSUE 30 • 2016 Discovering the Ocean’s Wonders Journey to the Inside of a Glacier Viking beer for the world. The Festival of Horses... 1,000 Years of Fish. www.icelandictimes.com ISSN 2298-6715 GRANDAGARÐI 8 101 REYKJAVÍK * 00354 456 4040 * WWW.BRYGGJANBRUGGHUS.IS TOURISM, CULT URE AND BUSINESS ISSUE 30 • 2016 ou may have noticed the tremendous growth in tourism to beers and wines, each with its own Iceland. Word is getting around that this small island, halfway specific flavour are produced in micro- between America and Russia, where the sun never sets in breweries, and enjoyed in the vibrant summer, has something special about it that other destinations lack. nightlife. YIcelandic culture and music is drawing thousands to festivals each All around the country, one of the year. Top orchestras vie to play in the new Harpa concert hall, which oldest industries has, in recent years, hosts an increasing number of major international conferences and seen a revolution take place. The conventions. Their participants are finding new, high quality hotels Icelandic fishing industry has grown to become a world leader, not rising up quickly in the capital. just in sustainable fishing but in all the ancilliary support industries, The air is pure. You can drink the water and relish its purity and with brilliant, young minds developing new technologies. Some of delicious taste. Lambs feast on mountain slopes covered with untainted these companies and their advances are to be found in the special herbs, also used for healthy cosmetics and in meals. Restaurants around section at the end of this issue. -

Press Release 27Th of May 2021

Press release 27th of May 2021. 4 Summer exhibitions in LÁ Art Museum open on 5th of June Let me walk in the moorland barefoot in a dress with seventeen singing plovers following me. Elísabet Jökulsdóttir The LÁ Art Museum summer shows – RÓSKA, Turbulence, Takeover & White – interface on many levels. The turbulence flows between galleries; from one time to another, one work to another, from the art to the visitors. RÓSKA – Impact and Inspiration Curator: Ástríður Magnúsdóttir It is a great honour to have the opportunity to present an exhibition of Róska’s art, and to communicate her campaigning spirit and visual world, which was beautiful, multi-layered, and provocative. Róska was an artist who had a powerful impact on her time and on later generations of artists; and many dimensions of her work have yet to be discovered and explored. She was unafraid of a cross-media approach in her art, and the same applies to the contemporary artists in Turbulence and Takeover. Their subjects relate, both overtly and more subtly, to the elements which were paramount to Róska in her art: the human, nature, feminism, the mystical, reiteration, lyrical simplicity, justice and humour. For more information please contact: Ástríður Magnúsdóttur t: 691 1960 [email protected] Turbulence Kristín Gunnlaugsdóttir has worked in a range of media, for instance with provocative paintings made using the age-old technique of egg-tempera and gold leaf on wood. In the exhibition Turbulence she shows pictures sewn on canvas, which are powerful and at the same time sensitive. The Icelandic Love Corporation, which was founded in 1996 and now comprises artists Eirún Sigurðardóttir and Jóní Jónsdóttir, has from the outset attracted great attention for works made in all possible media, to serve the concept in question. -

Schoen / CIA.IS - Center for Icelandic Art / Runólfsson / Et Al

Icelandic Art Today von Christian Schoen, CIA.IS - Center for Icelandic Art, Halldór Björn Runólfsson, The National Gallery of Iceland, Eva Heisler, Gregory Volk 1. Auflage Icelandic Art Today – Schoen / CIA.IS - Center for Icelandic Art / Runólfsson / et al. schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei beck-shop.de DIE FACHBUCHHANDLUNG Hatje Cantz Verlag 2009 Verlag C.H. Beck im Internet: www.beck.de ISBN 978 3 7757 2295 7 Icelandic Art Today 7 on oral history, the past not being manifested For names and places we likewise adhere to in architecture or pictures. The form of art that Icelandic spelling conventions. The Icelandic Preface developed in the early twentieth century was alphabet consists of 32 letters which mostly obliged to—and was indeed able to—survive correspond to the Latin ones (there is no C, Q, W without its own art history as a fundament or Z). All vowels (including Y) exist in a second to be based upon. Stimulation was instead form with an acute accent, which affects only Just what is it that makes Iceland’s art of today so taken mostly from international contemporary the pronunciation. In addition to the Latin letters different, so appealing? Be it from a conceptual, art. Its influence together with the autonomy there are the following letters ‘Ð/ð’ (like a vocal experimental, or poetic angle, today’s art in that comes from the country’s history and th in the word this), Þ/þ (this is nonvocal like the Iceland is what artists in other nations struggle geography continue to influence Icelandic art th in thing), Æ/æ (like the English ‘i’) and ‘Ö/ö’ to achieve: it is direct and genuine. -

Download Our Free Listings App - APPENING on the Apple and Android Stores

What we can learn from the #MeToo movement • Non-binary people in the vaccine lottery • Study the blade with HEMA! • KristÍn Þorkelsdóttir, the woman who designed Iceland • Possimiste, our favourite alien song- stress • Down to Earth at the Sky Lagoon • Ragnar Kjartansson talks 'Death Is Elsewhere' • Buy AMC! Two months into the Geldingadalir eruption, scientists are eager to decode its secrets COVER ART: Photographer: Art Bicnick The photo was taken at Fagradalsfjall, Iceland's newest volcano, just weeks after it began erupting. 10: Believe #MeToo 12-13: Ragnar "Paints" 23: Magma Masters 06: Moderna Odds Be 14: New Spots! 27: Regn Teaches Us Ever In Your Favour 20: Kristín Þorkelsdóttir Non-Binary Realness 08: The x_Emo_God_x Talks Her Life's Work 28: Soul Tacos First When the Grape- completely new. Everything from a EDITORIAL v i n e ’ s p h o t o lava tornado in the lava stream, to the editor Art Bicnick dramatic weather transforming the and I first visited area into something that even the best the Geldingadalir CGI in Hollywood could never recreate. volcano on March But the volcano also has some 2 0 t h w e w er e answers to provide and secrets to The Ever speechless. On unlock. In our feature about the scien- an Icelandic scale, the volcanic activ- tists researching the volcano on page ity was small and it was incredible how 10, it's evident that we have a scientific close we could safely get to the erup- goldmine on our hands, making this Changing tion. We realised instantly that this was eruption even more spectacular.