Vertical Integration, Exclusivity and Game Sales Performance in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

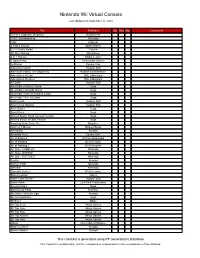

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 101-in-1 Explosive Megamix Nordcurrent 1080° Snowboarding Nintendo 1942 Capcom 2 Fast 4 Gnomz QubicGames 3-2-1, Rattle Battle! Tecmo 3D Pixel Racing Microforum 5 in 1 Solitaire Digital Leisure 5 Spots Party Cosmonaut Games ActRaiser Square Enix Adventure Island Hudson Soft Adventure Island: The Beginning Hudson Entertainment Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo 2 HAL Laboratory Air Zonk Hudson Soft Alex Kidd in Miracle World Sega Alex Kidd in Shinobi World Sega Alex Kidd: In the Enchanted Castle Sega Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Sega Alien Crush Hudson Soft Alien Crush Returns Hudson Soft Alien Soldier Sega Alien Storm Sega Altered Beast: Sega Genesis Version Sega Altered Beast: Arcade Version Sega Amazing Brain Train, The NinjaBee And Yet It Moves Broken Rules Ant Nation Konami Arkanoid Plus! Square Enix Art of Balance Shin'en Multimedia Art of Fighting D4 Enterprise Art of Fighting 2 D4 Enterprise Art Style: CUBELLO Nintendo Art Style: ORBIENT Nintendo Art Style: ROTOHEX Nintendo Axelay Konami Balloon Fight Nintendo Baseball Nintendo Baseball Stars 2 D4 Enterprise Bases Loaded Jaleco Battle Lode Runner Hudson Soft Battle Poker Left Field Productions Beyond Oasis Sega Big Kahuna Party Reflexive Bio Miracle Bokutte Upa Konami Bio-Hazard Battle Sega Bit Boy!! Bplus Bit.Trip Beat Aksys Games Bit.Trip Core Aksys Games Bit.Trip Fate Aksys Games Bit.Trip Runner Aksys Games Bit.Trip Void Aksys Games bittos+ Unconditional Studios Blades of Steel Konami Blaster Master Sunsoft This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Ubisoft Reports Full-Year 2007-08 Sales

Ubisoft reports full-year 2007-08 sales Full-year sales up 36% to €928 million. Target for 2008-09 current operating income 1 revised upwards. Paris, April 24, 2008 – Today, Ubisoft reported its sales for the fourth fiscal quarter ended March 31, 2008. Sales Sales for the fourth quarter of 2007-08 came to €217 million, up 10.0%, or 20.3% at constant exchange rates, compared with the €197 million recorded for the same period of 2006-07. Full-year sales for fiscal 2007-08 totaled €928 million, versus €680 million for fiscal 2006-07, representing an increase of 36.4%, or 42.9% at constant exchange rates. Fourth-quarter sales outstripped the initial guidance of approximately €165 million issued on January 23, 2008. This strong showing was driven by better-than-expected performances from the following games: Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six® Vegas 2, which reached almost 2 million sell-in units and ranked second in all-format sales for March in the United States and United Kingdom according to NPD and Chart-Track. The Games For Everyone (G4E) brands, which topped €230 million in sales for the year. Assassin's Creed ™, which continued its robust performance, achieving over 6 million sell-in units since its launch. During the first three months of the 2008 calendar year, Ubisoft continued to grow faster than the market 2 based on sell-through data: In the United States, Ubisoft posted growth of 38% (compared with 28% for the US market as a whole), with market share of 7.2% versus 6.7% in the first quarter of 2007. -

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Nintendo Co., Ltd

earnings releases May 30, 2002 Nintendo Co., Ltd. 11-1 Kamitoba hokotate-cho, Minami-ku, Kyoto 601-8501 Japan CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Nintendo Co., Ltd. and Consolidated Subsidiaries FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Years ended March 31, 2001 and 2002 The amounts presented herein are rounded down under one million yen except as otherwise denominated. Numbers in parentheses are negative. Yen in Millions 2001 2002 Net sales 462,502 554,886 Percentage change from previous year (12.8%) 20.0% Operating income 84,697 119,151 Percentage change from previous year (41.6%) 40.7% Income before income taxes and extraordinary items 192,247 186,618 Percentage change from previous year 77.5% (2.9%) Net income 96,603 106,444 Percentage change from previous year 72.3% 10.2% Net income per share --------------------------------------------------- ¥681.90 ¥751.39 Ratio of net income to net worth ------------------------------------------ 12.1% 12.0% Ratio of income before income taxes and extraordinary items to total assets -- 19.2% 16.8% Ratio of income before income taxes and extraordinary items to net sales ---- 41.6% 33.6% Financial position Total assets (1) --------------------------------------------- 1,068,568 1,156,715 Shareholders' equity (2) ------------------------------------- 834,951 935,075 Ratio of net worth to total assets (2) / (1) --------------------- 78.1% 80.8% Shareholders' equity per share ------------------------------- ¥5,893.71 ¥6,600.82 Cash flows Cash flows from operating activities ------------------------- 122,234 56,234 Cash -

Previews #306 (Vol. Xxiv #3, Mar14)

PREVIEWS #306 (VOL. XXIV #3, MAR14) PREVIEWS PUBLICATIONS PREVIEWS #308 MAY 2014 THIS MONTH’S COVER ART: New projects from Image and DC! THIS MONTH’S THEME: Women in Comics! Since 1988, PREVIEWS has been your ultimate source for all of the comics and merchandise to be available from your local comic book shop… revealed up to two months in advance! Hundreds of comics and graphic novels from the best comic publishers; the coolest pop-culture merchandise on Earth; plus PREVIEWS exclusive items available nowhere else! Now more than ever, PREVIEWS is here to show the tales, toys and treasures in your future! This May issue features items scheduled to ship in July 2014 and beyond. Catalog, 8x11, 500+pg, PC $4.50 PREVIEWS #308 CUSTOMER ORDER FORM — MAY 2014 PREVIEWS makes it easy for you to order every item in the catalog with this separate order form booklet! This May issue features items scheduled to ship in July 2014 and beyond. Comic-sized, 62pg, PC PI MARVEL PREVIEWS VOLUME 2 #22 Each issue of Marvel Previews is a comic book-sized, 120-page, full-color guide and preview to all of Marvel’s upcoming releases — it’s your #1 source for advanced information on Marvel Comics! This May issue features items scheduled to ship in July 2014 and beyond. FREE w/Purchase of PREVIEWS Comic-sized, 120pg, FC $1.25 COMICS SECTION PREMIER VENDORS DARK HORSE COMICS HATSUNE MIKU: UNOFFICIAL HATSUNE MIX TP KEI (W/A/Cover) On sale July 2 FC/b&w, 480 pages $19.99 TP, 5 3/4" x 8 1/4" Who's that girl with the long green ponytails you've been seeing everywhere? It's Hatsune Miku, the Vocaloid—the synthesizer superstar who's singing your song! She's a global cyber celebrity and a cosplay favorite at conventions. -

WHETHER You're LOOKING to COMPLETE the FUL SET

COLLECTORS' CORNER! WHETHER You’re lOOKING TO COMPLETE THE FUL SET, COLLECT ALL THE GAMES PUBLISHED IN THE FOUR MAIN TERRITORIES, OR MORE MODESTLY LIST THE TITLES YOU OWN, THE COLLECTor’s CORNER WAS MADE FOR YOU. TITLE PAGE ALTERNATE TITLE RELEASE RELEASE RELEASE DEVELOPER PUBLISHER DATE JP DATE NTSC DATE PAL 2020 SUPER BASEBALL 10 MONOLITH K AMUSEMENT LEASING (JP) / TRADEWEST (US) 3 NINJAS KICK BACK 10 l l MALIBU INTERACTIVE SONY IMAGESOFT 3×3 EYES JÛMA HÔKAN 10 l SYSTEM SUPPLY N-TECH BANPRESTO 3×3 EYES SEIMA KÔRINDEN 10 l NOVA GAMES YUTAKA GREAT BATTLE III (THE) 114 l SUN L BANPRESTO 4-NIN SHÔGI 10 l PLANNING OFFICE WADA PLANNING OFFICE WADA 7TH SAGA (THE) 10 ELNARD (JP) l PRODUCE GAMEPLAN21 (JP) / ENIX AMERICA (US) 90 MINUTES: EUROPEAN PRIME GOAL 11 J.LEAGUE SOCCER PRIME GOAL 3 (JP) l l NAMCO NAMCO (JP) / OCEAN (EU) A.S.P AIR STRIKE PATROL 11 DESERT FIGHTER (EU) l l OPUS SETA (JP-US) / SYSTEM 3 (EU) AAAHH!!! REAL MONSTERS 12 l l l REALTIME ASSOCIATES VIACOM NEW MEDIA ABC MONDAY NIGHT FOOTBALL 11 l l KÛSÔ KAGAKU DATA EAST ACCELE BRID 11 l Gl ENKI TOMY ACE O NERAE! 11 l TELENET JAPAN TELENET JAPAN ACME ANIMATION FACTORY 12 l PROBE SOFTWARE SUNSOFT ACROBAT MISSION 12 l l MICRONICS TECHIKU ACTION PACHIO 12 l C-LAB COCONUTS JAPAN ACTRAISER 13 l QUINTET ENIX (JP-EU) / ENIX AMERICA (US) ACTRAISER 2 14 ACTRAISER 2: CHINMOKU E NO SEISEN (JP) l l l QUINTET ENIX (JP) / ENIX AMERICA (US) / UBISOFT (EU) ADDAMS FAMILY (THE) 14 l l l OCEAN MISAWA (JP) / OCEAN (EU-US) ADDAMS FAMILY (THE): PUGSley’S SCAVENGER HUNT 14 l l l OCEAN OCEAN ADDAMS FAMILY VALUES 14 l l OCEAN OCEAN ADVANCED DUNGEONS & DRAGONS: EYE OF THE BEHOLDER 15 l Cl APCOM CAPCOM ADVENTURES OF BATMAN & ROBIN (THE) 15 l l KONAMI KONAMI ADVENTURES OF DR. -

1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die

1001 Video Games You Must Play Before You Die G = Completed B = Played R = Not played bold = in collection 1971-1980 (1 st GENERATION) 1. The Oregon Trail Multi-platform MECC 1971 2. Pong Multi-platform Atari 1972 1976-1992 (2 nd GENERATION) 3. Breakout Multi-platform Atari 1976 4. Boot Hill Arcade Midway 1977 5. Combat Atari 2600 Atari 1977 6. Space Invaders Arcade Taito 1978 7. Adventure Atari 2600 Atari 1979 8. Asteroids Arcade Atari 1979 9. Galaxian Arcade Namco 1979 10. Lunar Lander Arcade Atari 1979 11. Battle Zone Arcade Atari 1980 12. Defender Arcade Williams 1980 13. Eamon Apple II D. Brown 1980 14. Missile Command Arcade Atari 1980 15. Rogue Multi-platform M. Toy, G. Wichman, K. Arnold 1980 16. Tempest Arcade Atari 1980 17. MUD Multi-platform R. Trubshaw, R. Bartle 1980 18. Pac-Man Arcade Namco 1980 19. Phoenix Arcade Amstar Electronics 1980 20. Zork I Multi-platform Infocom 1980 21. Warlords Arcade / Atari 2600 Atari 1980 22. Centipede Arcade Atari 1980 23. Galaga Arcade Namco 1981 24. Donkey Kong Arcade Nintendo 1981 25. Qix Arcade R. Pfeiffer, S. Pfeiffer 1981 26. Scramble Arcade Konami 1981 27. Stargate Arcade Vid Kidz 1981 28. Venture Multi-platform Exidy 1981 29. Ms. Pac-Man Arcade Midway 1981 30. Frogger Arcade Konami 1981 31. Gorf Arcade Midway 1981 32. Ultima Multi-platform Origin Systems 1981 33. Gravitar Arcade Atari 1982 34. Joust Arcade Williams 1982 35. The Hobbit Multi-platform Beam Software 1982 36. Choplifter Multi-platform Brøderbund 1982 37. Robotron 2084 Arcade Williams 1982 38. -

会社案内 1 Side by Side; Overlapping , Representative Director and Make Them Now

www.success-corp.co.jp 会社案内 Greetings the Make the games you want, make them stand out, and make them now. from President Representative Director Takato Yoshinari In June of this year(2013) we were able to greet the 35th anniversary of our establishment. The histories of both video games and our company have evolved side by side; overlapping , so to speak. Therefore, may it not be said that we are a unique company within the game industry? In the period of these 35 years, the video game industry has completely changed our lifestyle. From the light-user, who enjoys a game while commuting, and during break time at his or her job, to a heavy-user who has no time to sleep because of playing with a video game, a large segment of society that enjoys the games has been formed throughout the nation. Nowadays, whenever we speak about our lives, we can hardly avoid speaking about video games. To have been witness to the entire formation process of this new game culture and to have been able to contribute to it, we consider ourselves very fortunate. Until now, we have sent out into the world more than 1200 titles of games, and from now on, also, we will make, and fervently, continue to make, as many interesting games as we can, ones which can be easily absorbed by anyone. This company having been allotted the destiny to make games, and with the readiness and willingness to follow it, we are, with pleasure, moving in the direction of further game-making. -

Patatine O Onigiri? Trasformazioni E Adattamenti Culturali Nella Localizzazione Dei Videogiochi

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Lingue e civiltà dell’Asia e dell’Africa mediterranea Tesi di Laurea Patatine o onigiri? Trasformazioni e adattamenti culturali nella localizzazione dei videogiochi Relatore Ch. Prof. Francesco Saverio Vitucci Correlatore Ch. Prof. Bonaventura Ruperti Laureando Federico Moia Matricola 833771 Anno Accademico 2014 / 2015 要旨 本論文はゲームローカライズについてである。ゲームローカライズというのはテレビゲーム・コ ンピューターゲーム・携帯型ゲームの文章を翻訳することだけでなく、その内容も海外の違っ た文化や好みに合わせることでもある。つまり、日本製のゲームを海外でも売れるように、日 本語から西洋の言語に翻訳したゲームコンテンツを部分的に、または全て書き改めることを必 要とすることでもある。その上、日本文化や日本語と西洋文化や西洋言語は非常に違ってい るだけあって、必要だと判断された変化は多くて、深い。その差異のせいで、昔は、日本製の ゲームが海外市場に輸出される時、度々そのゲームのコンテンツは変えられ、実物のゲーム の内容が、新しい部分と取り替えられなかったら、コンテンツが減少して不完全な製品になっ てしまった。実際に、当時は、ゲームローカライズはまだ実験段階にあり、不適切な翻訳ストラ テジーが多かったので、ゲームのコンテンツが、不相応だと考えられ、変化し、または検閲され ることは普通であった。しかし、運よくその時から、ゲームローカライズの実践は非常に成長し、 学術的な研究さえ次第に多くなってきた。そのかげで、日本製のゲームの中の内容、つまり日 本文化・考え方・習慣を失うことなく西洋へ持って来ることができ、ゲームの中の文化から、日 本の一般的な文化をよく理解するようになった。 本論文の目的はゲームローカライズの歴史、現状、これからの発達の仕方を研究することで ある。そのために、様々なローカライズしたゲームのケースと元のバージョンとの違いを分析し、 この課題を研究した学者の作品を参考にした。本論文は四章に分けられている。 第一章目では、ゲームローカライズの課題を一般的に述べる。始めに、ゲームローカライズの 定義を説明する。それから、様々な実例を挙げて、どんな内容が多くの場合変化に至るか、や その変化の理由を提示する。一般的に、ゲームのグラフィックはもっとも変化されている部分 で、その結果、ゲームの見た目は実物と非常に違ってくる。例えば、激しすぎて怖いと判断さ れたイメージだけでなく、エロチックなシーンも検閲される恐れがあるため、非常に変化を強い られたゲームのケースは多い。もちろん、ゲームの文も翻訳され、度々もとのバージョンと少し 違っている。ゲームは映像の作品だけあって、よく理解できるように、例をとして、多くのイメー ジを見せる。最後に、学者のローカライズによる理論などを発表する。 第二章目では、ゲームローカライズの歴史について話す。前述のとおり、ゲームの起源から今 1 日の超現実な製品の登場まで、ローカライズは非常に成長した。最初のゲームの時、ローカラ イズ標準がなく、それぞれのゲームがユニークな方法を使って、翻訳され、この不規則な仕方 の結果はあまり思わしくなかった。つまり、最初のゲームのローカライズと言えば、解決策が功 -

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Nintendo Co., Ltd

earnings releases November 21, 2001 Nintendo Co., Ltd. 11-1 Kamitoba hokotate-cho, Minami-ku, Kyoto 601-8501 Japan CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Nintendo Co., Ltd. and Consolidated Subsidiaries FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Six months ended September 30, 2000 and 2001, and year ended March 31, 2001 The amounts presented herein are rounded down under one million yen except as otherwise denominated. Numbers in parentheses are negative. Yen in Millions Sept. 30 Sept. 30 Mar. 31 2000 2001 2001 Net sales 190,634 225,722 462,502 Percentage change from previous half year - 18.4% Operating income 39,533 51,221 84,697 Percentage change from previous half year - 29.6% Income before income taxes and extraordinary items 62,729 51,557 192,247 Percentage change from previous half year - (17.8%) Net income 30,018 34,349 96,603 Percentage change from previous half year - 14.4% Net income per share ¥211.89 ¥242.47 ¥681.90 Financial position Total assets (1) 927,534 1,065,615 1,068,568 Shareholders' equity (2) 765,133 858,411 834,951 Ratio of net worth to total assets (2) / (1) 82.5% 80.6% 78.1% Shareholders' equity per share ¥5,400.89 ¥6,059.41 ¥5,893.71 Cash flows Cash flows from operating activities 11,640 ( 18,546) 122,234 Cash flows from investing activities ( 2,578) ( 65,151) 12,776 Cash flows from financing activities ( 8,456) ( 8,528) ( 16,451) Cash and cash equivalents - Ending 598,675 680,987 785,992 Scope of consolidation and equity method application Consolidated subsidiaries 24 (of which, newly added … 2 excluded … 0) Non-consolidated subsidiary with equity method applied 1 Affiliates with equity method applied 12 (of which, newly added … 0 excluded … 2) Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Nintendo Co., Ltd

earnings releases November 22, 2000 Nintendo Co., Ltd. Kyoto, Japan CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Nintendo Co., Ltd. and Consolidated Subsidiaries FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Six months ended September 30, 2000 and year ended March 31, 2000 The amounts presented herein are rounded down under one million yen except as otherwise denominated. Numbers in parentheses are negative. Yen in Millions Sept. 30 Mar. 31 2000 2000 Net sales 190,634 530,665 Percentage change from previous half year - Income from operations 39,533 145,030 Percentage change from previous half year - Income before income taxes and extraordinary items 62,729 108,338 Percentage change from previous half year - Net income 30,018 56,061 Percentage change from previous half year - Net income per share ¥211.89 ¥395.73 Since disclosure of interim consolidated financial statements starts in this period, the numbers and percentages of previous interim are left out. Financial position Total assets (1) 927,534 933,374 Shareholders' equity (2) 765,133 757,448 Ratio of net worth to total assets (2) / (1) 82.5% 81.2% Shareholders' equity per share ¥5,400.89 ¥5,346.71 Cash flows Cash flows from operating activities 11,640 93,053 Cash flows from investing activities ( 2,578) ( 64,476) Cash flows from financing activities ( 8,456) ( 16,895) Cash and cash equivalents at the end of year 598,675 594,062 Scope of consolidation and equity method application Consolidated subsidiaries 22 (of which, newly added … 2 excluded … 0) Non-consolidated subsidiary with equity method applied 1 Affiliated companies with equity method applied 11 (of which, newly added … 1 excluded … 0) Nintendo Co., Ltd. -

New Super Mario Bros. U (Wiiu), Borderlands 2(Ps3), Mass Effect 3 (PS3)

Downloaded from: justpaste.it/1k3w Eighty-ninth update – November 8, 2012 – Kingdom Hearts (3ds), Code of Princess (3ds), New Super Mario Bros. U (Wiiu), Borderlands 2(ps3), Mass effect 3 (PS3) Eighty-eighth update July 15, 2012 - King of Fighters XIII (PS3), Fallout 3 (PS3), Fallout New Vegas (PS3), Tales of Graces F (PS3), Donkey Kong Country Returns (Wii), Street Fighter X Tekken (PS3), SSX (PS3) eighty-sixthy update - April, 20, 2012 - Uncharted Golden Abyss (PSV), Wipeout 2048 (PSV), Lumines (PSV), Soul Calibur V (PS3), Xenoblade chronicles (Wii), Diablo 3 (PC) eighty-seven update - May 20, 2012 - Diseaga 3 (Vita), Dragon Force (Saturn), Valkyrie Profile (PS1), Breath of Fire IV (PS1), Shining Force CD (Sega CD), Ogre Tactics (PS1), Dragon Quest IV (SNES), Dragon Quest VI (SNES), Secret of Mana 2 (SNES), Tales of Phantasia (SNES), Terranigma (SNES), Soul Blazer (SNES), Tactics Ogre (PS1), Guardian Heroes (Saturn), Thunder Force V (PS1) eighty-sixth update - April, 20, 2012 - Uncharted Golden Abyss (PSV), Wipeout 2048 (PSV), Lumines (PSV), Soul Calibur V (PS3), Xenoblade chronicles (Wii), ZHF Unlosing Ranger vs. Darkdeath Evilman (PSP), Tales of Graces F (PS3), Mass Effect 3 (PC), Skies of Arcadia (GCN), Persona 2 (PSP), Persona 3 (PSP), Diseaga DS (DS), Diseaga (PSP) Diseaga 2 (PSP), Legend of Heroes (PSP) eighty-fifth update - January 27, 2012 - Dark Souls (PS3), Gears of War 3 (360), Super Mario 3D Land (3DS), Mario Kart 7 (3DS), Deus Ex: Human Revolution (PS3), Ratchet & Clank All 4 One (PS3), Batman: Arkham City (PS3), Elder -

TOKYO GAME SHOW 2013 Visitors Survey Report November 2013

TOKYO GAME SHOW 2013 Visitors Survey Report November 2013 Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association ■ Contents ■ Outline of Survey 3 I. Visitors' Characteristics 4 1. Gender ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 4 2. Age ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 4 3. Residential area ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 5 4. Occupation ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 5 5. Hobbies and interests ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 6 II. Household Videogames 9 1. Hardware ownership・Hardware most frequently used ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 9 2. Hardware the respondents wish to purchase ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 12 3. Use of game machine accessories ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 15 4. Favorite game genres ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 18 5. Frequency of game playing ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 22 6. Duration of game playing ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 24 7. Tendency of software purchases ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 27 8. Tendency of purchases of additional contents by downloading ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 31 III. Social Games 32 1. Familiarity with SNS and social games ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 32 2. Familiarity with social games ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐