Moving Youth Work Forward: Reflections on Youth-Centered Practice in Minnesota a COLLECTION of WORKING PAPERS PRODUCED by the MINNESOTA WALKABOUT FELLOWSHIP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elli Griff Set Decorator

Elli Griff Set Decorator Credits include: KNIVES OUT 2 Writer/Director: Rian Johnson Detective Comedy Crime Drama Producers: Ram Bergman, Rian Johnson Exec Producer: Tom Karnowski Designer: Rick Heinrichs Featuring: Daniel Craig, Dave Bautista, Kathryn Hayn Production Co: T-Street / Lionsgate / Netflix UNCHARTERED Director: Ruben Fleischer Action Adventure Producers: Ari Arad, Avi Arad, Alex Gartner, Charles Roven Designer: Shepherd Frankel Featuring: Tom Holland, Mark Wahlberg, Antonio Banderas Production Co: Atlas Ent. / Arad Productions Columbia Pictures / Sony Pictures THE DARK TOWER Director: Stephen Hopkins Adventure Fantasy Producers: Akiva Goldsman, Stephen King, Glen Mazzara Designer: Barry Robison Featuring: Michael Rooker, Sam Strike, Jerome Flynn Production Co: Amazon Studios / Sony Pictures Television THE ROOK Directors: Sunu Gonera, Rebecca Johnson Fantasy Thriller Drama Series China Moo-Young, Kari Skogland Exec Producer: Stephen Garrett Designer: Jonathan Lee Featuring: Emma Greenwell, Joely Richardson, Jon Fletcher Production Co: Character 7 / Lionsgate / Starz Originals GHOST IN THE SHELL Director: Rupert Sanders Sci-Fi Action Drama Producers: Ari Arad, Avi Arad, Michael Costigan, Steven Paul Designer: Jan Roelfs Featuring: Scarlett Johansson, Michael Pitt, Juliette Binoche Production Co: Paramount Pictures / DreamWorks / Reliance Ent. Arad Productions / Steven Paul Production / Amblin MISS PEREGRINE’S HOME FOR Director: Tim Burton PECULIAR CHILDREN Producers: Peter Chernin, Jenno Topping Adventure Fantasy Drama Designer: Gavin Bocquet Featuring: Eva Green, Asa Butterfield, Ella Purnell Production Co: Twentieth Century Fox / Chernin Ent. Creative Media Management | 10 Spring Bridge Mews | London | W5 2AB t: +44 (0)20 3795 3777 e: [email protected] w: creativemediamanagement.com Creative Media Management Limited Incorporated in England and Wales No: 3816049 VAT No: 739953576 Registered Office: 61 St Dunstans Road, London, W7 2EY Elli Griff | Set Decorator 2 THE MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E. -

Girl Scout Programs: Daisy

Learn It, Earn It! Cub and Girl Scout Badge Program 630-848-5000 • napervilleparks.org Learn It, Earn It! 2 Learn It, Earn It! The Naperville Park District is pleased to offer several new Learn It, Earn It! scout badge programs for local scout troops and dens. Group badge programs are designed to accomplish badge requirements. With over 30 programs for scouts, the Naperville Park District is your scouting headquarters for art, cooking, nature, science badges and more. Badge Programs • Badge programs are led by knowledgeable instructors who are Youth Protection trained/certified. • Programs are designed to fulfill badge requirements. Badge requirements covered are highlighted in the program descriptions and will be more detailed within your contract. • The program instructor will make every effort to cover the badge requirements listed under each badge program. However, some requirements or portions of a requirement may need to be completed during future scout meetings. • All Brownie, Junior and Cadette badge programs include badges for each participant. Daisy programs do not include badges. • Due to the complex nature of awarding beads, points, pins and/or badges upon completion of Cub Scout achievements and electives , the Park District does not provide these items. Cub Scout leaders are responsible for obtaining these recognition items for their scouts. • The Millennium Carillon Tour includes a special patch for each scout. • Some of the programs listed do not meet specific badge requirements but are designed to provide opportunities for fun, hands-on experiences that promote personal growth and exploration. Payment/Fees • Full payment is due at the time of registration. -

Antigua's Superyacht

On-line FEBRUARY 2008 NO. 149 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore Antigua’s Superyacht Cup See story on page 13 © KOS/KOSPICTURES.COM FEBRUARY 2008 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 2 FEBRUARY 2008 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 3 CALENDAR FEBRUARY 2 - 4 Martinique Carnival Regatta. Club Nautique Le Neptune (CNN), [email protected], www.clubnautiqueleneptune.com 3 - 6 Carnival Monday and Tuesday in most Dutch and French islands, Puerto Rico, Dominica, Carriacou, Trinidad & Tobago, Venezuela, and other places The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore 7 Independence Day. Public holiday in Grenada 9 - 10 St. Croix International Regatta. St. Croix Yacht Club (SCYC), www.caribbeancompass.com www.stcroixyc.com 13 - 17 Casa de Campo Regatta, Dominican Republic. FEBRUARY 2008 • NUMBER 149 www.casadecamporegatta.com 15 - 17 30th Annual Sweethearts of the Caribbean and 26th Annual Classic Yacht Regatta, Tortola. West End Yacht Club (WEYC), [email protected], www.weyc.net Bombs Away! 17 Sailors’ and Landlubbers’ Auction, Bequia. (784) 457-3047 Visiting Vieques.....................24 18 Presidents’ Day. Public holiday in Puerto Rico and USVI 20 Lunar Eclipse visible throughout the Caribbean 21 FULL MOON 21 - 24 Grenada Classic Yacht Regatta. www.ClassicRegatta.com 22 Independence Day. Public holiday in St. Lucia. Yacht races 24 Bonaire International Fishing Tournament. www.infobonaire.com 27 Independence Day. Public holiday in Dominican Republic TBA Non-Stop Around Martinique Race. CNN TBA Semaine Nautique Schoelcher, Martinique. [email protected] Small Island… …big launching! ....................17 MARCH Labor of Love 1 Spanish Town Fishermen’s Jamboree and 12th Annual Plastic classic renewed ..........18 Wahoo Tournament, BVI 3 H. -

Enhancement of Forest Canopy Research, Education, and Conservation in the New Millennium

Plant Ecology 153: 361-367,2001. O 2001 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlunds. Enhancement of forest canopy research, education, and conservation in the new millennium Nalini M. Nadkarni The Evergreen State College, Olympia, WA 98505, USA (e-mail: [email protected]) Key words: Conservation, Forest Canopy, Graduate Study, Rain forests Abstract Study of the forest canopy has reached a critical stage in its development from a young 'frontier' area of study to a vibrant and coalescing field of investigation and communication. Many current environmental and social issues at global scales (e.g., environmental change, acid deposition, loss of biodiversity) are related directly to our knowledge of forest canopies. I present six activities that are needed to help the vibrant and growing field of forest canopy studies progress efficiently. Enabling canopy researchers to communicate with each other and with those outside our field is an important element to address these issues. The establishment of a graduate-level training program is also a high priority to generate and maintain a healthy discipline. Formal procedures to identify particular forest sites of critical concern should be initiated, and these should include communication of prioritized sites to conservation groups and policy makers. Instilling a sense of wonder and appreciation for organisms and interactions in non-scientists is another important avenue for forest canopy conservation. Introduction (Lugo & Scatena 1992; Benzing 1998). The bulk of the photosynthetic machinery of the biosphere is lo- The forest canopy has been termed 'the last biotic cated within forest canopies, so understanding their frontier', and is one of the richest but most poorly physiology and interactions has tremendous impor- studied habitats in the biosphere (Lowman & Nad- tance on issues relating to global carbon budgets and karni 1995). -

Bruxy Cavey and the Meeting House Megachurch: a Dramaturgical Model of Charismatic Leadership Performing “Evangelicalism for People Not Into Evangelicalism”

Bruxy Cavey and The Meeting House Megachurch: A Dramaturgical Model of Charismatic Leadership Performing “Evangelicalism for People Not Into Evangelicalism” by Peter Schuurman A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Peter Schuurman 2016 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ! ii ! Abstract Megachurch pastors—as local and international celebrities—have been a growing phenomenon since the 1960s, when megachurches began to proliferate across North America. Why are these leaders and their large congregations so popular in an age of increasing “religious nones”? Commentators in both popular and academic literature often resort to characterizing the leadership with stereotypes of manipulative opportunists along the lines of Sinclair Lewis’ Elmer Gantry (1927) or narrow characterizations of savvy entrepreneurs who thrive in a competitive religious economy. Similarly, writers assume megachurch attendees are a passive audience, or even dupes. This dissertation challenges the Elmer Gantry stereotype and the religious economic perspectives by examining one particular megachurch pastor named Bruxy Cavey in the context of his “irreligious” megachurch community called -

To Build Or Not to Build Project Learning Objectives November 2003

Millennium Quest High School | Highway Construction in a Local Neighborhood | Denver, CO To Build or Not to Build Project Learning Objectives November 2003 Measurable Objectives All students will: Understand eminent domain Understand industrialism (history of and how the environment took a “hit”) Read charts and graphs Read a government budget Calculate using percentage Understand which decisions affect environmental racism Define contamination: what and quantity Understand the effects of contamination Know about clean-up models (like Superfund) Understand the potential hazardous effects of public transportation Describe the model for funding federal highways Know the history of at least these three Denver neighborhoods: Elyria-Swansea, Globeville, and 5 Points Design an instrument to conduct a survey or conduct a personal interview Use the Internet to obtain resources/information Experiential Objectives Appreciate how complex decisions get made Learn on one’s own Competency in a new technology (Palm Pilot) Ability to access “real world” people The reality of deadlines Frustrations of leadership and responsibility Compromise “Real world” power struggles Millennium Quest High School | Highway Construction in a Local Neighborhood | Denver, CO I-70 East Corridor including Light Rail Options Student Study Project Research Wrap-up February 26, 2004 Sunny Walker, facilitator Millennium Quest High School AGENDA Introductions Walkabout to View Team Exhibits Clarify Information/Key Facts to Consider in Making a Decision Brainstorm Our Recommendations CLARIFY INFORMATION 1. No decision has been made. 2. EIS means Environmental Impact Study, DEIS means Draft Environmental Impact Study 3. Main issue is pollution to air, soil, water from factories, transportation (buses, cars, trucks) 4. EIS is being done on the highway from the I-70/I-25 interchange (the “mousetrap”) to Peña Boulevard and a rapid transit system (light rail or “fastrack”) from Union Station through Stapleton to DIA 5. -

Roebling and the Brooklyn Bridge

BOOK SUMMARY She built a monument for all time. Then she was lost in its shadow. Discover the fascinating woman who helped design and construct an American icon, perfect for readers of The Other Einstein. Emily Warren Roebling refuses to live conventionally―she knows who she is and what she wants, and she's determined to make change. But then her husband Wash asks the unthinkable: give up her dreams to make his possible. Emily's fight for women's suffrage is put on hold, and her life transformed when Wash, the Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge, is injured on the job. Untrained for the task, but under his guidance, she assumes his role, despite stern resistance and overwhelming obstacles. Lines blur as Wash's vision becomes her own, and when he is unable to return to the job, Emily is consumed by it. But as the project takes shape under Emily's direction, she wonders whose legacy she is building―hers, or her husband's. As the monument rises, Emily's marriage, principles, and identity threaten to collapse. When the bridge finally stands finished, will she recognize the woman who built it? Based on the true story of the Brooklyn Bridge, The Engineer's Wife delivers an emotional portrait of a woman transformed by a project of unfathomable scale, which takes her into the bowels of the East River, suffragette riots, the halls of Manhattan's elite, and the heady, freewheeling temptations of P.T. Barnum. It's the story of a husband and wife determined to build something that lasts―even at the risk of losing each other. -

Walking Wounded

Walking Wounded: Cinematic Representations of Masculine, Post-Modern Anxiety in the Urban Space Penelope Eate B. Soc. Sc. (Hons) Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Gender, Work and Social Inquiry, School of Social Sciences University of Adelaide February, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... v Declaration ............................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. vii INTRODUCTION __________________________________________ 1 CHAPTER ONE Going Nowhere: Urban Strolling as Masculine Anxiety In and Out of the Nineteenth Century __________________________________________ 18 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 18 The Physiology of the Urban Sketcher.................................................................................... 19 Flânerie as Crisis ...................................................................................................................... 20 Detecting Dissent in Edgar Allan Poe‟s „The Man of The Crowd‟ (1845) ......................... 22 The Politics of Location: Gender and Public Space ............................................................. -

The 6Os Communes Messianic Communities) Bus at Bellows Falls) Vermont

The 6os Communes Messianic Communities) bus at Bellows Falls) Vermont. Photograph by Timothy Miller. TIMOTHY MILLER The 60s Communes Hippies and Beyond Syracuse UniversityPress Copyright © 1999 by Syracuse UniversityPress, Syracuse, New York 13244-5160 AllRights Reserved First Edition 1999 02 03 04 05 06 6 5 4 3 2 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard forInformation Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANS I z39.48-1984.@ LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG ING -IN-PUBLICATI ON DATA Miller, Timothy, 1944- The 6os communes : hippies and beyond/ Timothy Miller. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8156-2811-0 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 0-8156-0601-x (pbk.: alk. paper) I. Communal living-United States. 2. United States-Social conditions- 1960-1980. I. Title. II. Title: Sixties communes. III. Title: Hippies and beyond. HQ97I.M55 1999 307.77'4'0973-dc21 99-37768 Manufactured in the United States of America For Michael) Gretchen) andJeffre y TIMOTHY MILLER is professor of religious studies at the University of Kansas. Among his previous publica tions is The Quest forUt opia in Twentieth-CenturyAm erica: 1900-1960) the first of three volumes on communal life to be published by Syracuse UniversityPress. Contents Acknowledgments IX Introduction xm I. Set and Setting: The Roots of the 196os-Era Communes I 2. The New Communes Emerge: 1960-1965 17 3. Communes Begin to Spread: 1965-1967 41 4. Out of the Haight and Back to the Land: Countercultural Communes after the Summer of Love 67 5. Searching for a Common Center: Religious and Spiritual Communes 92 6. -

Monitored This Issue

April 26, 2017 | No. 842 Dear readers of the WISE/NIRS Nuclear Monitor, In this issue of the Monitor: • Diet Simon writes about the German environment minister’s refusal to halt nuclear fuel shipments to high-risk reactors in neighboring Belgium. • We summarize an important critique of (terrestrial) fusion Monitored this issue: power by experienced fusion scientist Dr Daniel Jassby, who argues that it is not the ideal energy source extolled German environment minister’s dangerous 2 by its boosters but is “something to be shunned.” schizophrenia on nuclear fuel exports ‒ Diet Simon • We summarize new reports on the record-breaking Fusion scientist debunks fusion power 4 growth of renewable energy sources in 2016 and a significant shift away from coal power. 2016 another record year for renewables 5 • We write about Canadian uranium company Cameco’s Cameco battling uranium 7 continuous downsizing over the past five years, its downturn, tax office, TEPCO legal battle with the Canadian tax office over profit- Cameco’s incidents and accidents: 1981‒2016 10 shifting allegations, and its battle against TEPCO’s termination of a long-term supply contract. • And we detail many of the accidents, incidents and scandals that Cameco has been involved in since 1981. Feel free to contact us if you have feedback on this issue of the Monitor, or if there are topics you would like to see covered in future issues. April 26 marks the 31st anniversary of the Chernobyl disaster. Operators in Regards from the editorial team. the control room of reactor #4 (pictured) committed a series of errors during a safety test, triggering a reactor meltdown that resulted in the world’s largest Email: [email protected] nuclear accident to date. -

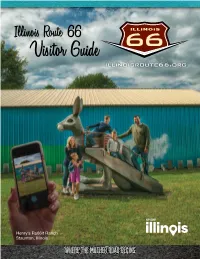

Visitor Guide

Welcome to Illinois Route 66 The Experience of a Lifetime! The Mother Road in Illinois is the place to search out the perfect piece of homemade pie, neon signs you won’t see anywhere else, an honest-to-goodness rabbit ranch, and a whole slew of larger and small towns that truly are the “real America.” For all event listings and other up-to-date information visit: illinoisroute66.org Map and History Restaurants pics on 66 pages 2 and 3 page 4 page 5 breweries museums Abraham Lincoln on 66 page 7 page 8 page 9 events downtown districts giants page 10 page 12 page 13 interpretive exhibits page 16 community listings pages 17-58 outdoors pages 32-33 neon vintage 66 Lodging pages 60-62 page 15 page 14 more info page 64 Printed in the U.S.A. April 2020 50M Index of Communities The communities in this visitors guide are listed as they are found along Route 66 traveling from north to south. If you are looking for information on a particular community, please use the table of contents below with corresponding page numbers. Atlanta ...................................37 Auburn ..................................51 Benld .....................................53 Berwyn ..................................18 Bloomington ..........................31 Bolingbrook ...........................20 Braceville ...............................25 Braidwood .............................25 Broadwell ..............................42 Carlinville ...............................52 Cayuga ..................................26 Channahon ............................20 Chatham -

A Walkabout Tour of Historic Bradmore

A WALKABOUT TOUR OF HISTORIC BRADMORE Originally published by Bradmore Millennium Committee A WALKABOUT TOUR OF HISTORIC BRADMORE Published as a booklet by the Bradmore Millennium Committee Bradmore, April 2000, and copied for publishing on the village website 2016. Bradmore’s history at a glance Guide to the village and its history Village Map Field Map Villagers’ reminiscences of the 20th century Acknowledgements The booklet is written by present and past members of the village community. The history group members were Gwenda Ackroyd, Sheila Clark, Jack Garner, Kathleen Hogg, Garrie Naden, Mike Peregrine and John Randall. Other contributions – written and verbal, photographs and maps – came from Marion Bagguley, Robert Bagguley, Enid Hofton, Valerie Jackson, Dorothy Jesson, Helen Miller, Mary Morley, Dorothy Onyon, Ann Peregrine and Holly Scothern, Win Randall, Doris and George Randall, Sally Starling, Stef and Gill Zelynskyj, and from earlier work by Oliver Randall, Neville Waddingham and John Bishton. All contributions are gratefully acknowledged. Thanks are also due to the Parish Council and the Bradmore Millennium Committee for initiating and supporting the work, to the staff at the Nottinghamshire Archives for instruction and patient help to amateur researchers, to Judy Clifford for reviewing and advising on the final text, and not least to all the villagers who have supported the enterprise with their interest and encouragement. This booklet draws on previous publications, notably Miss M H Hill’s ‘History of Bunny and Bradmore’, John Smeeton’s 1939 Nottingham Guardian article ‘Bradmore of the Nineties’, Oliver Randall’s ‘Bradmore the Village and Methodism 1830-1980’, Bob Hine’s ‘The Morris Dancers of Bradmore’ and Notts Industrial Archaeology Society Journal September 1981 on Bradmore Windmill.