The Impact of the Air Cargo Industry on the Global Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December, 2005

CoverINT 11/21/05 3:05 PM Page 1 WWW.AIRCARGOWORLD.COM DECEMBER 2005 INTERNATIONAL EDITION Cargo’s New Directions the 2005-2006 Review & Outlook Saving Fuel • Latin America • Buying BAX 01TOCINT 11/21/05 11:56 AM Page 1 INTERNATIONAL EDITION December 2005 CONTENTS Volume 8, Number 10 REGIONS Review & 10 North America Outlook Air cargo traffic fell back Cargo carriers are looking at 2220 to earth in 2005 after 2004’s creative ways to reduce sky high strong growth. What’s on fuel costs • Delta Crisis tap for 2006? 12 Europe An integrated Air France/ KLM aims to be the word’s lead- ing international cargo airline 16 Pacific Asian carriers are fretting over a peak season that may be too little, too late Buying 20 Latin America Anti-trade sentiments and BAX restrictive regulations cool air 4 Deutsche Bahn’s pur- cargo growth in the region chase of the U.S. logistics operator adds to the speedy consolidation of global freight transport. 2006 DEPARTMENTS Corporate 2 Edit Note 29 Oulook 4 News Updates Special Advertising Sec- 35 Events tion provides companies’ pro- jections on the year ahead. 36 People 38 Bottom Line 40 Commentary WWW.aircargoworld.com Air Cargo World (ISSN 0745-5100) is published monthly by Commonwealth Business Media. Editorial and production offices are at 1270 National Press Building, Washington, DC, 20045. Telephone: (202) 355-1172. Air Cargo World is a registered trademark of Commonwealth Business Media. ©2005. Periodicals postage paid at Newark, NJ and at additional mailing offices. Subscription rates: 1 year, $58; 2 year $92; outside USA surface mail/1 year $78; 2 year $132; outside US air mail/1 year $118; 2 year $212. -

World Airline Cargo Report Currency and Fuel Swings Shift Dynamics

World Airline Cargo Report Currency and fuel swings shift dynamics Changing facilities Asia’s handlers adapt LCCs and cargo Handling rapid turnarounds Cool chain Security technology Maintaining pharma integrity Progress and harmonisation 635,1*WWW.CAASINT.COM www.airbridgecargo.com On Time Performance. Delivered 10 YEARS EXPERIENCE ON GLOBAL AIR CARGO MARKET Feeder and trucking delivery solutions within Russia High on-time performance Online Track&Trace System Internationally recognized Russian cargo market expert High-skilled staff in handling outsize and heavy cargo Modern fleet of new Boeing 747-8 Freighters Direct services to Russia from South East Asia, Europe, and USA Direct services to Russian Far East (KHV), Ural (SVX), and Siberian region (OVB, KJA) AirBridgeCargo Airlines is a member of IATA, IOSA Cool Chain Association, Cargo 2000 and TAPA Russia +7 495 7862613 USA +1 773 800 2361 Germany +49 6963 8097 100 China +86 21 52080011 IOSA Operator The Netherlands +31 20 654 9030 Japan +81 3 5777 4025 World Airline PARVEEN RAJA Cargo Report Currency and fuel swings shift dynamics Publisher Changing facilities [email protected] Asia’s handlers adapt LCCs and cargo Handling rapid turnarounds Cool chain Security technology Maintaining pharma integrity Progress and harmonisation 635,1*WWW.CAASINT.COM SIMON LANGSTON PROMISING SIGNS Business Development Manager here are some apparently very positive trends highlighted [email protected] and discussed in this issue of CAAS, which is refreshing for a sector that often goes round in -

Automated Flight Statistics Report For

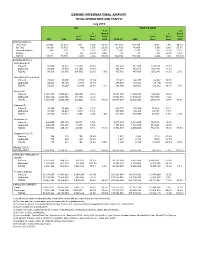

DENVER INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT TOTAL OPERATIONS AND TRAFFIC July 2010 July YEAR TO DATE % of % of % Grand % Grand Incr./ Incr./ Total Incr./ Incr./ Total 2010 2009 Decr. Decr. 2010 2010 (9) 2009 Decr. Decr. 2010 OPERATIONS (1) Air Carrier 42,054 41,412 642 1.6% 73.7% 271,866 269,130 2,736 1.0% 74.1% Air Taxi 14,569 13,761 808 5.9% 25.5% 92,769 86,804 5,965 6.9% 25.3% General Aviation 400 393 7 1.8% 0.7% 2,073 2,079 (6) -0.3% 0.6% Military 8 12 (4) -33.3% 0.0% 82 91 (9) -9.9% 0.0% TOTAL 57,031 55,578 1,453 2.6% 100.0% 366,790 358,104 8,686 2.4% 100.0% PASSENGERS (2) International (3) Inbound 50,854 62,421 (11,567) -18.5% 376,293 421,396 (45,103) -10.7% Outbound 47,469 60,635 (13,166) -21.7% 374,289 426,424 (52,135) -12.2% TOTAL 98,323 123,056 (24,733) -20.1% 1.9% 750,582 847,820 (97,238) -11.5% 2.5% International/Pre-cleared Inbound 37,682 30,097 7,585 25.2% 232,432 166,370 66,062 39.7% Outbound 34,523 29,170 5,353 18.4% 230,434 163,254 67,180 41.2% TOTAL 72,205 59,267 12,938 21.8% 1.4% 462,866 329,624 133,242 40.4% 1.5% Majors (4) Inbound 1,963,129 2,003,643 (40,514) -2.0% 11,491,709 11,586,595 (94,886) -0.8% Outbound 1,960,236 2,004,666 (44,430) -2.2% 11,526,782 11,639,633 (112,851) -1.0% TOTAL 3,923,365 4,008,309 (84,944) -2.1% 77.5% 23,018,491 23,226,228 (207,737) -0.9% 76.6% National (5) Inbound 38,190 36,695 1,495 4.1% 212,141 193,469 18,672 9.7% Outbound 38,140 36,227 1,913 5.3% 209,256 194,340 14,916 7.7% TOTAL 76,330 72,922 3,408 4.7% 1.5% 421,397 387,809 33,588 8.7% 1.5% Regionals (6) Inbound 443,456 420,139 23,317 5.5% 2,677,209 -

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report January, 2012

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report January, 2012 This Month Calendar Year to Date 2012 2011 %Chg 2012 2011 %Chg Total PDX Flight Operations * 15,907 17,573 -9.5% 15,907 17,573 -9.5% Military 295 255 15.7% 295 255 15.7% General Aviation 1,372 1,408 -2.6% 1,372 1,408 -2.6% Hillsboro Airport Operations 12,834 11,335 13.2% 12,834 11,335 13.2% Troutdale Airport Operations 4,813 3,455 39.3% 4,813 3,455 39.3% Total System Operations 33,554 32,363 3.7% 33,554 32,363 3.7% PDX Commercial Flight Operations ** 13,642 15,144 -9.9% 13,642 15,144 -9.9% Cargo 1,698 2,042 -16.8% 1,698 2,042 -16.8% Charter 4 14 -71.4% 4 14 -71.4% Major 5,738 5,912 -2.9% 5,738 5,912 -2.9% National 440 362 21.5% 440 362 21.5% Regional 5,762 6,814 -15.4% 5,762 6,814 -15.4% Domestic 13,188 14,660 -10.0% 13,188 14,660 -10.0% International 454 484 -6.2% 454 484 -6.2% Total Enplaned & Deplaned Passengers 974,082 964,699 1.0% 974,082 964,699 1.0% Charter 301 1,059 -71.6% 301 1,059 -71.6% Major 653,855 626,343 4.4% 653,855 626,343 4.4% National 61,882 54,568 13.4% 61,882 54,568 13.4% Regional 258,044 282,729 -8.7% 258,044 282,729 -8.7% Total Enplaned Passengers 484,783 485,192 -0.1% 484,783 485,192 -0.1% Total Deplaned Passengers 489,299 479,507 2.0% 489,299 479,507 2.0% Total Domestic Passengers 947,137 935,041 1.3% 947,137 935,041 1.3% Total Enplaned Passengers 471,806 470,957 0.2% 471,806 470,957 0.2% Total Deplaned Passengers 475,331 464,084 2.4% 475,331 464,084 2.4% Total International Passengers 26,945 29,658 -9.1% 26,945 29,658 -9.1% Total Enplaned -

2008 Annual Report Air Transport Services Group 2008 Annual Report

SM 2008 Annual Report Air Transport Services Group 2008 Annual Report To Our Shareholders 2008 was bound to be a year of dramatic the $91.2 million in impairment charges, full-year change for us. Shortly after our acquisition of Cargo pre-tax earnings increased 36 percent to $45.4 Holdings International (CHI) at the end of 2007, we million, versus $33.3 million for 2007. For the full were informed that our principal customer, DHL, year, our revenues were up 37 percent to $1.6 intended to dramatically restructure its U.S. operations. billion. This growth can be attributed primarily to DHL’s decision in May 2008 to pursue an air transport our CHI businesses, which contributed revenue of and sorting agreement for domestic freight with its $352.7 million for the year. Likewise, cash fl ows competitor UPS came as a tremendous shock. generated from operations increased to $161.7 million in 2008, up from $95.5 million in 2007. Just as disappointing, however, was DHL’s decision last November to suspend its domestic services in favor of handling only inbound and Operating Cash Flow 2004-2008 outbound international shipments for its global customers. Those decisions, together with the U.S. economic recession, have substantially $162M reduced the scale of our operations for DHL. $119M They also have cost us the valued contributions of thousands of men and women who had served us, and DHL, very well over the years. Wilmington, the southwest Ohio community where we are $96M based, has experienced severe economic distress. We are doing our best to remain a supportive $55M $65M corporate citizen in Wilmington, and have funded and taken an active role in many groups seeking long-term solutions to the region’s diffi culties. -

Wisconsin-Madison and Texas A&M Transportation Institute

Air Cargo in the Mid-America Freight Coalition Region Teresa M. Adams, Ph.D. Scott Janowiak, Jason Bittner, Benjamin R. Sperry, Jeffery E. Warner, Jeffrey D. Borowiec, Ph.D. University of Wisconsin-Madison and Texas A&M Transportation Institute WisDOT ID no. 0092-11-09 CFIRE ID no. 04-11 August 2012 Research & Library Unit National Center for Freight & Infrastructure Research & Education University of Wisconsin-Madison WISCONSIN DOT PUTTING RESEARCH TO WORK Air Cargo in the Mid-America Freight Coalition Region CFIRE 04-11 CFIRE August 2012 National Center for Freight & Infrastructure Research & Education Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering College of Engineering University of Wisconsin–Madison Authors: Teresa M. Adams, Scott Janowiak, Jason Bittner University of Wisconsin–Madison Benjamin R. Sperry, Jeffery E. Warner, Jeffrey D. Borowiec Texas A&M Transportation Institute Principal Investigator: Teresa M. Adams National Center for Freight & Infrastructure Research & Education University of Wisconsin–Madison 2 Technical Report Documentation 1. Report No. CFIRE 04-11 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. CFDA 20.701 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date August 2012 Air Cargo in the Mid-America Freight Coalition Region 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author/s 8. Performing Organization Report No. Scott Janowiak, Teresa M. Adams, and Jason Bittner, CFIRE, University of CFIRE 04-11 Wisconsin–Madison Benjamin R. Sperry, Jeffery E. Warner, and Jeffrey D. Borowiec. Texas A&M Transportation Institute 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) National Center for Freight and Infrastructure Research and Education (CFIRE) University of Wisconsin-Madison 11. Contract or Grant No. -

Volume 22: Number 1 (2004)

Estimating Airline Employment: The Impact Of The 9-11 Terrorist Attacks David A. NewMyer, Robert W. Kaps, and Nathan L. Yukna Southern Illinois University Carbondale ABSTRACT In the calendar year prior to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, U. S. Airlines employed 732,049 people according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics [BTS] of the U. S. Department of Transportation (Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U. S. Department of Transportation [BTS], 2001). Since the 9-11 attacks there have been numerous press reports concerning airline layoffs, especially at the "traditional," long-time airlines such as American, Delta, Northwest, United and US Airways. BTS figures also show that there has been a drop in U. S. Airline employment when comparing the figures at the end of the calendar year 2000 (732,049 employees) to the figures at the end of calendar year 2002 (642,797 employees) the first full year following the terrorist attacks (BTS, 2003). This change from 2000 to 2002 represents a total reduction of 89,252 employees. However, prior research by NewMyer, Kaps and Owens (2003) indicates that BTS figures do not necessarily represent the complete airline industry employment picture. Therefore, one key purpose of this research was to examine the scope of the post 9-11 attack airline employment change in light of all available sources. This first portion of the research compared a number of different data sources for airline employment data. A second purpose of the study will be to provide airline industry employment totals for both 2000 and 2002, if different from the BTS figures, and report those. -

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report August, 2010

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report August, 2010 This Month Calendar Year to Date 2010 2009 %Chg 2010 2009 %Chg Total PDX Flight Operations * 20,295 20,518 -1.1% 150,344 153,148 -1.8% Military 332 429 -22.6% 2,748 2,974 -7.6% General Aviation 2,166 2,083 4.0% 14,500 14,373 0.9% Hillsboro Airport Operations 20,149 20,068 0.4% 157,334 158,499 -0.7% Troutdale Airport Operations 6,036 6,782 -11.0% 38,315 52,276 -26.7% Total System Operations 46,480 47,368 -1.9% 345,993 363,923 -4.9% PDX Commercial Flight Operations ** 16,494 16,448 0.3% 122,624 124,714 -1.7% Cargo 2,220 2,252 -1.4% 17,668 17,806 -0.8% Charter 10 4 150.0% 70 58 20.7% Major 6,954 6,788 2.4% 50,108 51,698 -3.1% National 426 372 14.5% 3,064 2,618 17.0% Regional 6,884 7,032 -2.1% 51,714 52,534 -1.6% Domestic 16,372 16,154 1.3% 118,864 121,114 -1.9% International 122 294 -58.5% 3,760 3,600 4.4% Total Enplaned & Deplaned Passengers 1,322,198 1,299,478 1.7% 8,764,322 8,742,636 0.2% Charter 623 281 121.7% 4,421 3,841 15.1% Major 893,326 882,326 1.2% 5,858,946 5,918,522 -1.0% National 71,325 61,711 15.6% 478,206 413,721 15.6% Regional 356,924 355,160 0.5% 2,422,749 2,406,552 0.7% Total Enplaned Passengers 666,576 655,781 1.6% 4,377,425 4,367,180 0.2% Total Deplaned Passengers 655,622 643,697 1.9% 4,386,897 4,375,456 0.3% Total Domestic Passengers 1,272,967 1,245,523 2.2% 8,468,989 8,418,571 0.6% Total Enplaned Passengers 642,176 628,730 2.1% 4,230,321 4,203,580 0.6% Total Deplaned Passengers 630,791 616,793 2.3% 4,238,668 4,214,991 0.6% Total International Passengers -

Confidential Garvinm@Stlouis-Mo

LAMBERT-ST. LOUIS INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT MASTER PLAN UPDATE CHAPTER THREE FORECAST OF AVIATION DEMAND Notes to Aviation Activity Forecasts: Sections 3.1 through 3.10 reflect forecasts prepared and published in June 2009. These forecasts were approved by the FAA on August 27, 2009. Appendix A reflects a sensitivity analysis conducted in November 2009 and published in final in August 2010. The June 2009 forecasts were re-approved by the FAA on September 27, 2010 pursuant to FAA review of the sensitivity analysis. INTRODUCTION This chapter presents comprehensive forecasts of aviation demand for the Lambert-St. Louis International Airport (STL or Lambert Airport) Master Plan Update for the years 2013, 2018, 2023, and 2028. The aviation activity forecast is a critical component in the master planning process. Future activity levels were projected for annual passenger enplanements, air cargo volumes, and aircraft operations. In addition, peak period (monthly, daily, and hourly) forecasts were also prepared to guide the planning process. Forecasts of aviation demand for the purpose of planning future facilities were last prepared in 1996 when STL functioned as a major hub for Trans World Airlines (TWA). At the turn of the decadeConfidential, TWA succumbed to financial difficulties and was purchased by American Airlines. American has since reduced the size of the hub considerably resulting in a significant reduction in connecting traffic at the airport. As a result, STL has changed from being a predominantly connecting hub to an airport primarily servicing demand for travel to and from the St. Louis metropolitan area. As the passenger [email protected] has changed, the mix of carriers and mix of aircraft has also changed. -

Future Aviation Activities

TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH CIRCULAR Number E-C051 January 2003 Future Aviation Activities 12th International Workshop TRANSPORTATION Number E-C051, January 2003 RESEARCH ISSN 0097-8515 CIRCULAR Future Aviation Activities 12th International Workshop Sponsored by COMMITTEE ON AVIATION ECONOMICS AND FORECASTING (A1J02) COMMITTEE ON LIGHT COMMERCIAL AND GENERAL AVIATION (A1J03) Workshop Committee Cochairs Gerald W. Bernstein, Stanford Transportation Group Chair, Committee on Aviation Economics and Forecasting (A1J02) Gerald S. McDougall, Southeast Missouri State University Chair, Committee on Light Commercial and General Aviation (A1J03) Panel Leaders Richard S. Golaszewski David Lawrence Joseph P. Schwieterman GRA, Inc. Aviation Market Research, LLC DePaul University Geoffrey D. Gosling Derrick Maple Anne Strauss-Wieder Aviation System Planning Smiths Aerospace A. Strauss-Wieder, Inc. Consultant Gerald S. McDougall Ronald L. Swanda Tulinda Larsen Southeast Missouri State General Aviation BACK Aviation Solutions University Manufacturers Association Joseph A. Breen, TRB Staff Representative Subscriber Category Transportation Research Board V aviation 500 5th Street, NW www.TRB.org Washington, DC 20001 The Transpo rtation Research Board is a division of the National Research Council, which serves as an independent adviser to the federal government on scientific and technical questions of national importance. The National Research Council, jointly administered by the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine, brings the resources of the entire scientific and technical community to bear on national problems through its volunteer advisory committees. The Transportation Research Board is distributing this Circular to make the information contained herein available for use by individual practitioners in state and local transportation agencies, researchers in academic institutions, and other members of the transportation research community. -

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report March, 2012

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report March, 2012 This Month Calendar Year to Date 2012 2011 %Chg 2012 2011 %Chg Total PDX Flight Operations * 17,437 17,919 -2.7% 48,759 51,135 -4.6% Military 367 293 25.3% 1,021 843 21.1% General Aviation 1,736 1,522 14.1% 4,629 4,177 10.8% Hillsboro Airport Operations 16,398 14,655 11.9% 42,769 40,720 5.0% Troutdale Airport Operations 6,870 3,092 122.2% 18,198 9,360 94.4% Total System Operations 40,705 35,666 14.1% 109,726 101,215 8.4% PDX Commercial Flight Operations ** 14,874 15,626 -4.8% 41,606 44,466 -6.4% Cargo 1,944 2,288 -15.0% 5,446 6,294 -13.5% Charter 4 6 -33.3% 12 24 -50.0% Major 6,390 6,390 0.0% 17,594 17,614 -0.1% National 428 396 8.1% 1,258 1,096 14.8% Regional 6,108 6,546 -6.7% 17,296 19,438 -11.0% Domestic 14,398 15,130 -4.8% 40,240 43,042 -6.5% International 476 496 -4.0% 1,366 1,424 -4.1% Total Enplaned & Deplaned Passengers 1,125,870 1,101,092 2.3% 3,033,034 2,953,484 2.7% Charter 315 496 -36.5% 927 1,838 -49.6% Major 762,967 737,913 3.4% 2,038,533 1,938,913 5.1% National 62,789 60,664 3.5% 179,813 165,063 8.9% Regional 299,799 302,019 -0.7% 813,761 847,670 -4.0% Total Enplaned Passengers 576,028 552,486 4.3% 1,527,664 1,484,747 2.9% Total Deplaned Passengers 549,842 548,606 0.2% 1,505,370 1,468,737 2.5% Total Domestic Passengers 1,094,981 1,068,860 2.4% 2,952,186 2,866,761 3.0% Total Enplaned Passengers 559,995 536,890 4.3% 1,487,500 1,443,065 3.1% Total Deplaned Passengers 534,986 531,970 0.6% 1,464,686 1,423,696 2.9% Total International Passengers 30,889 32,232 -

2016 Annual Report Air Transport Services Group 2016 Annual Report

SM 2016 Annual Report Air Transport Services Group 2016 Annual Report To Our Shareholders In 2016, ATSG achieved its best revenue growth under price of $9.73 per share. We issued warrants for nearly 9 the business model we adopted in 2010, and one of the million shares in 2016, and will issue warrants for another best growth years in our history. Revenues rose 24 percent, 3.8 million shares this year. None have been exercised to or $150 million, to $769 million as we substantially date. But over time, Generally Accepted Accounting expanded our 767 fleet and placed more of them with key Principles (GAAP) require us to reflect their value in our global companies. Revenue growth excluding fuel and financial statements and their potential issuance in our other reimbursed expenses increased 18 percent. diluted share counts. That growth was spread across our principal business These warrant effects, which are non-cash, mask a units. It stemmed largely from groundbreaking significant portion of our operating earnings and cash agreements we signed in March with our newest customer, generating strength. Consolidated net earnings from Amazon Fulfillment Services. Our positive outlook for continuing operations in 2016 were $21.1 million, or 33 2017 and 2018 is for more growth and an even more cents per share diluted, which were lower than in 2015. diversified revenue base. DHL and Amazon, our two Those 2016 earnings, however, included a combined $16.5 largest customers, accounted for 34 and 29 percent, million, or 25 cents per share in non-cash after-tax respectively, of our revenues in 2016.