Wisconsin-Madison and Texas A&M Transportation Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airline Activity Report

1 $LUOLQH$FWLYLW\5HSRUW 0D\21 $LUOLQHDFWLYLW\GDWDLVSURYLGHGE\WKHDLUOLQHVDQGLVVXEMHFWWRFKDQJH:KLOHZHPDNHHYHU\DWWHPSWWRHQVXUHWKHGDWDUHSRUWHGLVDFFXUDWHWKH ,QGLDQDSROLV$LUSRUW$XWKRULW\ ,$$ LVQRWUHVSRQVLEOHIRUWKHDFFXUDF\RIWKHGDWD,$$DVVXPHVQROLDELOLW\IURPHUURUVRURPLVVLRQVLQWKLVGDWD Indianapolis International Airport 2 Airline Activity Summary For Month Ending May 2021 Passenger Domestic May (cur) May (pre) Difference % Change YTD May (cur) YTD May (pre) Difference % Change Scheduled Deplaning 306,675 51,091 255,584 500.3% 1,119,719 991,586 128,133 12.9% Enplaning 309,632 53,864 255,768 474.8% 1,103,966 955,766 148,200 15.5% Subtotal 616,307 104,955 511,352 487.2% 2,223,685 1,947,352 276,333 14.2% Charter Deplaning 1,784 158 1,626 1029.1% 6,832 4,826 2,006 41.6% Enplaning 1,598 0 1,598 100.0% 6,804 4,919 1,885 38.3% Subtotal 3,382 158 3,224 2040.5% 13,636 9,745 3,891 39.9% Total Domestic 619,689 105,113 514,576 489.5% 2,237,321 1,957,097 280,224 14.3% International Deplaning 656 0 656 100.0% 5,238 17,628 -12,390 -70.3% Enplaning 652 0 652 100.0% 5,029 15,324 -10,295 -67.2% Total International 1,308 0 1,308 100.0% 10,267 32,952 -22,685 -68.8% Total Deplaning 309,115 51,249 257,866 503.2% 1,131,789 1,014,040 117,749 11.6% Total Enplaning 311,882 53,864 258,018 479.0% 1,115,799 976,009 139,790 14.3% Total Passengers 620,997 105,113 515,884 490.8% 2,247,588 1,990,049 257,539 12.9% Air Cargo (in tons) Mail Inbound 60 32 28 87.8% 386 438 -52 -11.8% Outbound 90 55 35 64.1% 424 502 -79 -15.7% Subtotal Mail 150 87 63 72.8% 810 940 -130 -13.8% Freight -

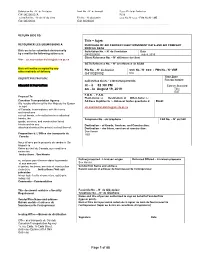

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

Dekalb County Airport Business Plan GWB

2016 DeKalb County Airport Business Plan GWB DeKalb County Airport Authority 6/17/2016 DeKalb County Airport Business Plan 2016 Airport Authority Board Brad Hartz – President George Wappes – Vice President John Chalmers – Secretary John Harris – Member Jess Myers – Member Airport Authority Staff Russ Couchman – Airport Manager Jason Hoit – Assistant Manager Sebastian Baumgardner - Maintenance Gene Powell - Maintenance Fixed Base Operator/Century Aviaiton Lara Gaerte - Owner Tony Gaerte - Owner Nick Diehl Larry Peters Steve McMurray DCAA Business Plan 1 DeKalb County Airport Business Plan 2016 Table of Contents Section Page Executive Summary….…………………………………………………………….……….………………4 Business Plan Basis…………………………..………………………………………………………………8 Background………………………………………………………………………………………………….….9 Goals, Objectives and Action Plans…………………………………………………………………20 Appendices……………………………………………………………………………………………………. Appendix A – Additional Goals, Objectives and Action Plans Appendix B – Business Plan Survey Appendix C – Business Plan Survey Results Appendix D – Indiana Airports Economic Impact Study Executive Summary Appendix E – FAA Asset Study, Regional Airports Excerpt Appendix F – DCAA 2016-2021 Capital Improvement Plan/Funding Summary Appendix G – Future Airport Layout Plan Drawing DCAA Business Plan 2 DeKalb County Airport Business Plan 2016 Page Intentionally Left Blank DCAA Business Plan 3 DeKalb County Airport Business Plan 2016 Executive Summary The DeKalb County Airport (GWB) is a Regional General Aviation Airport that is a significant part of the economic development activity, commerce and transportation in Northeast Indiana. The Airport, in it’s over half a century of operation, has developed into an all-season, all-weather corporate-class facility which successfully competes with its peers, regardless of size. The purpose of this plan is to move the DeKalb County Airport Authority (DCAA) strategically into a more positive, community focused entity while relying less on tax revenues, over time. -

Industry Clusters |Aviation and Aerospace

AVIATION-AEROSPACE MAJOR AEROSPACE COMPANIES EMPLOYMENT SECTORS INDUSTRY CLUSTERS AVG. COMPANY LINE OF BUSINESS INDUSTRY ESTABLISHMENTS EMPLOYMENT AVIATION DFW’S A.E. Petsche Company Aerospace electrical equipment 35E SEARCH, DETECTION, 19 3,819 AND AEROSPACE NAVIGATION Airbase Services, Inc. Maintenance & repair services 35W AEROSPACE Airbus Helicopters, Inc Helicopter parts Dallas-Fort Worth is among the nation’s ECONOMIC 106 31,307 PRODUCT AND PARTS American Airlines / AMR Corporation Air transportation top regions for aviation and aerospace MANUFACTURING121 Applied Aerodynamics, Inc Maintenance & repair services activity. The region is home to the AIR TRANSPORTATION 140 37,453 ENGINE Aviall Inc Parts distribution and maintenance headquarters of two major airlines: 35E SUPPORT ACTIVITIES FOR 268 12,003 BAE Systems Controls Inc Aircraft parts and equipment | American Airlines (Fort Worth)35W and AIR TRANSPORTATION Southwest Airlines (Dallas). Southwest, in 121 Bell Helicopter Textron Inc Helicopters, Aircraft parts, and equipment SATELLITE 12 105 AEROSPACE AND AVIATION fact, operates a major maintenance base TELECOMMUNICATIONS Boeing Company Commerical and military aircraft at Dallas Love Field, creating a strong Bombardier Aerospace Corp Aviation services FLIGHT TRAINING 43 1,724 foundation of aviation employment. Envoy 190 190 CAE, Inc Vocational school Air, a regional jet operator and American TOTAL 588 86,411 Chromalloy Component Services, Inc Aircraft parts and equipment Airlines partner, also is headquartered in Cooperative Industries Aerospace Aircraft engines and engine parts Fort Worth. 75 The regional aerospace industry Dallas Airmotive Aircraft engine repair 30 comprises more than 900820 companies, 183 Duncan Aviation Aircraft parts and equipment accounting for one of every six jobs in EFW Inc Aircraft and helicopter repair 12 North Texas. -

CARES ACT GRANT AMOUNTS to AIRPORTS (Pursuant to Paragraphs 2-4) Detailed Listing by State, City and Airport

CARES ACT GRANT AMOUNTS TO AIRPORTS (pursuant to Paragraphs 2-4) Detailed Listing By State, City And Airport State City Airport Name LOC_ID Grand Totals AK Alaskan Consolidated Airports Multiple [individual airports listed separately] AKAP $16,855,355 AK Adak (Naval) Station/Mitchell Field Adak ADK $30,000 AK Akhiok Akhiok AKK $20,000 AK Akiachak Akiachak Z13 $30,000 AK Akiak Akiak AKI $30,000 AK Akutan Akutan 7AK $20,000 AK Akutan Akutan KQA $20,000 AK Alakanuk Alakanuk AUK $30,000 AK Allakaket Allakaket 6A8 $20,000 AK Ambler Ambler AFM $30,000 AK Anaktuvuk Pass Anaktuvuk Pass AKP $30,000 AK Anchorage Lake Hood LHD $1,053,070 AK Anchorage Merrill Field MRI $17,898,468 AK Anchorage Ted Stevens Anchorage International ANC $26,376,060 AK Anchorage (Borough) Goose Bay Z40 $1,000 AK Angoon Angoon AGN $20,000 AK Aniak Aniak ANI $1,052,884 AK Aniak (Census Subarea) Togiak TOG $20,000 AK Aniak (Census Subarea) Twin Hills A63 $20,000 AK Anvik Anvik ANV $20,000 AK Arctic Village Arctic Village ARC $20,000 AK Atka Atka AKA $20,000 AK Atmautluak Atmautluak 4A2 $30,000 AK Atqasuk Atqasuk Edward Burnell Sr Memorial ATK $20,000 AK Barrow Wiley Post-Will Rogers Memorial BRW $1,191,121 AK Barrow (County) Wainwright AWI $30,000 AK Beaver Beaver WBQ $20,000 AK Bethel Bethel BET $2,271,355 AK Bettles Bettles BTT $20,000 AK Big Lake Big Lake BGQ $30,000 AK Birch Creek Birch Creek Z91 $20,000 AK Birchwood Birchwood BCV $30,000 AK Boundary Boundary BYA $20,000 AK Brevig Mission Brevig Mission KTS $30,000 AK Bristol Bay (Borough) Aleknagik /New 5A8 $20,000 AK -

Indiana State Aviation System Plan Airports Based Aircraft History

Indiana State Aviation System Plan Airports Based Aircraft History Aviation Facility Associated City 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Aviation Facility Anderson Municipal Anderson 79 74 73 76 75 78 71 67 72 68 75 71 63 70 67 57 68 71 65 70 72 72 79 80 77 85 81 73 Anderson Municipal Steuben Co.-Tri State Angola 24 22 25 25 27 29 29 32 30 34 34 32 30 31 34 30 31 33 33 34 42 39 40 35 34 38 39 37 Steuben Co.-Tri State DeKalb County Auburn 30 32 38 32 35 32 29 30 34 33 47 47 45 57 51 44 48 56 65 66 64 60 66 67 63 64 67 63 DeKalb County Virgil I. Grissom Bedford 38 35 36 28 28 30 31 28 29 29 29 32 31 34 30 31 33 35 31 34 31 32 31 29 27 28 29 28 Virgil I. Grissom Monroe County Bloomington 63 68 80 82 82 86 88 77 79 80 78 94 88 87 99 99 94 100 102 103 101 101 98 105 113 108 117 111 Monroe County Brazil-Clay County Brazil 10 12 11 10 10 11 12 9 11 13 11 11 10 14 12 14 14 16 15 13 16 17 16 18 17 17 14 15 Brazil-Clay County Clinton Clinton 14 11 13 14 14 13 13 12 11 11 11 12 12 16 13 13 11 9 9 9 11 11 10 11 11 12 13 11 Clinton Columbus Municipal Columbus 75 74 69 66 68 66 67 63 71 75 75 87 82 72 84 80 81 80 76 76 70 75 73 76 78 73 67 67 Columbus Municipal Mettel Field Connersville 19 15 15 16 15 16 17 21 21 17 15 13 10 8 11 14 11 10 11 12 14 11 12 11 13 7 8 8 Mettel Field Crawfordsville Municipal Crawfordsville 27 29 29 27 28 28 29 31 32 33 32 38 36 30 30 32 27 29 31 27 27 29 33 33 31 34 31 34 Crawfordsville Municipal Delphi Municipal Delphi 15 17 16 14 8 8 12 12 14 14 14 20 20 22 23 21 21 22 25 26 31 29 27 26 25 27 26 24 Delphi Municipal Elkhart Municipal Elkhart 93 97 96 97 88 84 82 87 79 72 85 81 70 94 85 84 80 75 60 70 92 99 111 111 123 119 146 147 Elkhart Municipal Evansville Regional Evansville 84 72 73 73 64 73 75 75 79 81 79 87 79 90 85 85 89 87 79 77 68 73 64 63 63 59 55 57 Evansville Regional Ft. -

December, 2005

CoverINT 11/21/05 3:05 PM Page 1 WWW.AIRCARGOWORLD.COM DECEMBER 2005 INTERNATIONAL EDITION Cargo’s New Directions the 2005-2006 Review & Outlook Saving Fuel • Latin America • Buying BAX 01TOCINT 11/21/05 11:56 AM Page 1 INTERNATIONAL EDITION December 2005 CONTENTS Volume 8, Number 10 REGIONS Review & 10 North America Outlook Air cargo traffic fell back Cargo carriers are looking at 2220 to earth in 2005 after 2004’s creative ways to reduce sky high strong growth. What’s on fuel costs • Delta Crisis tap for 2006? 12 Europe An integrated Air France/ KLM aims to be the word’s lead- ing international cargo airline 16 Pacific Asian carriers are fretting over a peak season that may be too little, too late Buying 20 Latin America Anti-trade sentiments and BAX restrictive regulations cool air 4 Deutsche Bahn’s pur- cargo growth in the region chase of the U.S. logistics operator adds to the speedy consolidation of global freight transport. 2006 DEPARTMENTS Corporate 2 Edit Note 29 Oulook 4 News Updates Special Advertising Sec- 35 Events tion provides companies’ pro- jections on the year ahead. 36 People 38 Bottom Line 40 Commentary WWW.aircargoworld.com Air Cargo World (ISSN 0745-5100) is published monthly by Commonwealth Business Media. Editorial and production offices are at 1270 National Press Building, Washington, DC, 20045. Telephone: (202) 355-1172. Air Cargo World is a registered trademark of Commonwealth Business Media. ©2005. Periodicals postage paid at Newark, NJ and at additional mailing offices. Subscription rates: 1 year, $58; 2 year $92; outside USA surface mail/1 year $78; 2 year $132; outside US air mail/1 year $118; 2 year $212. -

World Airline Cargo Report Currency and Fuel Swings Shift Dynamics

World Airline Cargo Report Currency and fuel swings shift dynamics Changing facilities Asia’s handlers adapt LCCs and cargo Handling rapid turnarounds Cool chain Security technology Maintaining pharma integrity Progress and harmonisation 635,1*WWW.CAASINT.COM www.airbridgecargo.com On Time Performance. Delivered 10 YEARS EXPERIENCE ON GLOBAL AIR CARGO MARKET Feeder and trucking delivery solutions within Russia High on-time performance Online Track&Trace System Internationally recognized Russian cargo market expert High-skilled staff in handling outsize and heavy cargo Modern fleet of new Boeing 747-8 Freighters Direct services to Russia from South East Asia, Europe, and USA Direct services to Russian Far East (KHV), Ural (SVX), and Siberian region (OVB, KJA) AirBridgeCargo Airlines is a member of IATA, IOSA Cool Chain Association, Cargo 2000 and TAPA Russia +7 495 7862613 USA +1 773 800 2361 Germany +49 6963 8097 100 China +86 21 52080011 IOSA Operator The Netherlands +31 20 654 9030 Japan +81 3 5777 4025 World Airline PARVEEN RAJA Cargo Report Currency and fuel swings shift dynamics Publisher Changing facilities [email protected] Asia’s handlers adapt LCCs and cargo Handling rapid turnarounds Cool chain Security technology Maintaining pharma integrity Progress and harmonisation 635,1*WWW.CAASINT.COM SIMON LANGSTON PROMISING SIGNS Business Development Manager here are some apparently very positive trends highlighted [email protected] and discussed in this issue of CAAS, which is refreshing for a sector that often goes round in -

2015 Indiana Airport Directory

Indiana Airport Directory CITY AIRPORT Alexandria Alexandria Airport Airport Manager Central Indiana Soaring Society Mr. David Colclasure (317) 373-6317 Business Business Address: 1577 E. 900 N. Alexandria, IN 46001 Email Address: [email protected] Airport President Central Indiana Soaring Society Mr. Tim Woenker Airport Vice President Central Indiana Soaring Society Mr. David Waymire Airport Secretary Central Indiana Soaring Society Mr. Scot Ortman Airport Treasurer Central Indiana Soaring Society Mr. Scot Ortman Internet Information Central Indiana Soaring Society Mr. David Waymire Email Address: [email protected] 9/1/2015 Indiana Department of Transportation Office of Aviation Page 1 of 116 Indiana Airport Directory Anderson Anderson Municipal Airport Airport Manager Mr. John Coon (765) 648-6293 Business (765) 648-6294 Fax Business Address: 282 Airport Road Anderson, IN 46017 Email Address: [email protected] Airport Board President Mr. Rodney French Airport Board Vice President Mr. Rick Senseney Airport Board Secretary Ms. Diana Brenneke Airport Board Member Mr. Steve Givens Airport Board Member Mr. David Albea Airport Consultant CHA, Companies Internet Information www.cityofanderson.com 9/1/2015 Indiana Department of Transportation, Office of Aviation Page 2 of 116 Indiana Airport Directory Angola Crooked Lake Seaplane Base Airport Manager Major Michael Portteus (317) 233-3847 Business (317) 232-8035 Fax (812) 837-9536 Dispatch Business Address: 402 W. Washington St. Rm W255D Indianapolis, IN 46204 Email Address: [email protected] Airport Owner Indiana Department of Natural Resources (317) 233-3847 Business (317) 232-8035 Fax Business Address: 402 W. Washington St. Room W255D Indianapolis, IN 46204 9/1/2015 Indiana Department of Transportation, Office of Aviation Page 3 of 116 Indiana Airport Directory Angola Lake James Seaplane Base Airport Manager Major Michael Portteus (317) 233-3847 Business (317) 232-8035 Fax (812) 837-9536 Dispatch Business Address: 402 W. -

IS-BAO Registrations : Operators | IS-BAO Organizations On-Line Listing Sep-25-2021 09:51 AM

IS-BAO Registrations : Operators | IS-BAO Organizations On-Line Listing Sep-25-2021 09:51 AM IS-BAO Organizations On-Line Listing Organization City Country Registration ID# BestFly Limitada Luanda Angola 750 Revesco Aviation Pty Ltd Perth Australia 187 Walker Air Service Mascot Australia 2628 Royal Flying Doctor Service of Australia (Queensland Section) Brisbane Australia 2384 Australian Corporate Jet Centres Pty Ltd Essendon Australia 756 Consolidated Press Holdings Pty Ltd Sydney Australia 361 Westfield/LFG Aviation Group Australia Sydney Australia 339 Business Aviation Solutions Bilinga Australia 2283 ExecuJet Australia Mascot Australia 510 International Jet Management GmbH Schwechat Austria 2319 Avcon Jet Wien Austria 2290 Sparfell Luftfahrt GmbH Schwechat Austria 2385 Tyrolean Jet Services GmbH Innsbruck Austria 274 Squadron Aviation Services Ltd Hamilton Bermuda 189 Trans World Oil Ltd. dba T.W.O. Air (Bermuda) Ltd Hamilton Bermuda 197 S&K Bermuda Ltd. Pembroke Bermuda 45 Minera San Cristobal S.A. La Paz Bolivia 733 Vale SA Rio de Janeiro Brazil 560 AVANTTO Administração de Aeronaves Sao Paulo Brazil 654 PAIC Participacoes Ltda Sao Paulo Brazil 480 Lider Taxi Aereo S/A Brasil Belo Horizonte Brazil 48 EMAR Taxi Aereo Rio das Ostras Brazil 2615 ICON Taxi Aereo Ltda. São Paulo Brazil 2476 Banco Bradesco S/A Osasco Brazil 2527 M. Square Holding Ltd. Road Town British Virgin Islands 2309 London Air Services Limited dba London Air Services South Richmond Canada 2289 Chartright Air Group Mississauga Canada 432 ACASS Canada Ltd. Montreal Canada 102 Sunwest Aviation Ltd Calgary Canada 105 Air Partners Corporation Calgary Canada 764 Coulson Aviation (USA) Inc. -

Mainline Flight Attendants

September 2017 Aero Crew News Your Source for Pilot Hiring Information and More... Exclusive Hiring Briefing SKY HIGH PAY. FLOW TO AA. There’s never been a better time to join the largest provider of regional service for American Airlines. • Up to $22,100 sign-on bonus • Make nearly $60,000 your first year ($37.90/hour + bonuses) • $20,000 retention bonus after one year of service • Convenient bases in Chicago (ORD) and Dallas/Fort Worth (DFW), with LaGuardia (LGA) base opening in 2017 • Flow to American Airlines in about six years -- no additional interview Find out more on envoyair.com www.envoyair.com | [email protected] | +1 972-374-5607 contents September 2017 Letter From the Publisher 8 41st Annual Convention for OBAP Aviator Bulletins 10 Latest Industry News Pilot Perspectives 16 It Pays to be Personable 30 MILLION-AIR 20 The Four Biggest Financial Mistakes And How To Avoid Them Fitness Corner 24 BPA Hazards and Flight Crews Contract Talks 28 Open Time Food Bites 30 34 Choo Choo Barbecue Skylaw 32 The “New” FAA Compliance Philosophy Exclusive Hiring Feature 34 Southern Airway Express Cockpit 2 Cockpit 42 OBAP After-Action Report 42 Jump to each section above by clicking on the title or photo. the grids Sections Airlines in the Grid Updated Legacy FedEx Express The Mainline Grid 50 Alaska Airlines Kalitta Air Legacy, Major, Cargo & FA American Airlines UPS International Airlines Delta Air Lines General Information Hawaiian Airlines Regional US Airways Work Rules Air Wisconsin United Airlines Additional Compensation Details -

Airport Listings of General Aviation Airports

Appendix B-1: Summary by State Public New ASSET Square Public NPIAS Airports Not State Population in Categories Miles Use Classified SASP Total Primary Nonprimary National Regional Local Basic Alabama 52,419 4,779,736 98 80 75 5 70 18 25 13 14 Alaska 663,267 710,231 408 287 257 29 228 3 68 126 31 Arizona 113,998 6,392,017 79 78 58 9 49 2 10 18 14 5 Arkansas 53,179 2,915,918 99 90 77 4 73 1 11 28 12 21 California 163,696 37,253,956 255 247 191 27 164 9 47 69 19 20 Colorado 104,094 5,029,196 76 65 49 11 38 2 2 27 7 Connecticut 5,543 3,574,097 23 19 13 2 11 2 3 4 2 Delaware 2,489 897,934 11 10 4 4 1 1 1 1 Florida 65,755 18,801,310 129 125 100 19 81 9 32 28 9 3 Georgia 59,425 9,687,653 109 99 98 7 91 4 18 38 14 17 Hawaii 10,931 1,360,301 15 15 7 8 2 6 Idaho 83,570 1,567,582 119 73 37 6 31 1 16 8 6 Illinois 57,914 12,830,632 113 86 8 78 5 9 35 9 20 Indiana 36,418 6,483,802 107 68 65 4 61 1 16 32 11 1 Iowa 56,272 3,046,355 117 109 78 6 72 7 41 16 8 Kansas 82,277 2,853,118 141 134 79 4 75 10 34 18 13 Kentucky 40,409 4,339,367 60 59 55 5 50 7 21 11 11 Louisiana 51,840 4,533,372 75 67 56 7 49 9 19 7 14 Maine 35,385 1,328,361 68 36 35 5 30 2 13 7 8 Maryland 12,407 5,773,552 37 34 18 3 15 2 5 6 2 Massachusetts 10,555 6,547,629 40 38 22 22 4 5 10 3 Michigan 96,716 9,883,640 229 105 95 13 82 2 12 49 14 5 Minnesota 86,939 5,303,925 154 126 97 7 90 3 7 49 22 9 Mississippi 48,430 2,967,297 80 74 73 7 66 10 15 16 25 Missouri 69,704 5,988,927 132 111 76 4 72 2 8 33 16 13 Montana 147,042 989,415 120 114 70 7 63 1 25 33 4 Nebraska 77,354 1,826,341 85 83