In the Realm of the Four Quarters 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Making Popular and Solidarity Economies in Dollarized Ecuador: Money, Law, and the Social After Neoliberalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3xx5n43g Author Nelms, Taylor Campbell Nahikian Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Making Popular and Solidarity Economies in Dollarized Ecuador: Money, Law, and the Social After Neoliberalism DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Anthropology by Taylor Campbell Nahikian Nelms Dissertation Committee: Professor Bill Maurer, Chair Associate Professor Julia Elyachar Professor George Marcus 2015 Portion of Chapter 1 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All other materials © 2015 Taylor Campbell Nahikian Nelms TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: “The Problem of Delimitation”: Expertise, Bureaucracy, and the Popular 51 and Solidarity Economy in Theory and Practice CHAPTER 2: Saving Sucres: Money and Memory in Post-Neoliberal Ecuador 91 CHAPTER 3: Dollarization, Denomination, and Difference 139 INTERLUDE: On Trust 176 CHAPTER 4: Trust in the Social 180 CHAPTER 5: Law, Labor, and Exhaustion 216 CHAPTER 6: Negotiable Instruments and the Aesthetics of Debt 256 CHAPTER 7: Interest and Infrastructure 300 WORKS CITED 354 ii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1 Field Sites and Methods 49 Figure 2 Breakdown of Interviewees 50 Figure 3 State Institutions of the Popular and Solidarity Economy in Ecuador 90 Figure 4 A Brief Summary of Four Cajas (and an Association), as of January 2012 215 Figure 5 An Emic Taxonomy of Debt Relations (Bárbara’s Portfolio) 299 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Every anthropologist seems to have a story like this one. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

“Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia” by Robert W. Jones, Jr. 6 Veritas is a land of sharp physical and social contrasts. Although blessed with Benormousolivia mineral wealth Bolivia was (and is) one of the poorest nations of Latin America and has been described as a “Beggar on a Throne of Gold.” 1 This article presents a short description of Bolivia as it appeared in 1967 when Che Guevara prepared to export revolution to the center of South America. In Guevara’s estimation, Bolivia was ripe for revolution with its history of instability and a disenfranchised Indian population. This article covers the geography, history, and politics of Bolivia. Geography and Demographics Bolivia’s terrain and people are extremely diverse. Since geography is a primary factor in the distribution of the population, these two aspects of Bolivia will be discussed together. In the 1960s Bolivian society was predominantly rural and Indian unlike the rest of South America. The Indians, primarily Quechua or Aymara, made up between fifty to seventy percent of the population. The three major Indian dialects are Quechua, Aymara, and Guaraní. The remainder of the population were whites and mixed races (called “mestizos”). It is difficult to get an accurate census because The varied geographic regions of Bolivia make it one of the Indians have always been transitory and there are the most climatically diverse countries in South America. cultural sensitivities. Race determines social status in Map by D. Telles. Bolivian society. A mestizo may claim to be white to gain vegetation grows sparser towards the south, where social status, just as an economically successful Indian the terrain is rocky with dry red clay. -

Collision of Civilizations

Collision of Civilizations Spaniards, Aztecs and Incas 1492- The clash begins Only two empires in the New World Cahokia Ecuador Aztec Empire The Aztec State in 1519 • Mexico 1325 Aztecs start to build their capital city, Tenochtitlan. • 1502 Montezuma II becomes ruler, wars against the independent city-states in the Valley of Mexico. The Aztec empire was in a fragile state, stricken with military failures, economic trouble, and social unrest. Montezuma II had attempted to centralize power and maintain the over-extended empire expanded over the Valley of Mexico, and into Central America. It was an extortionist regime, relied on force to extract prisoners, tribute, and food levies from neighboring peoples. As the Aztec state weakened, its rulers and priests continued to demand human sacrifice to feed its gods. In 1519, the Aztec Empire was not only weak within, but despised and feared from without. When hostilities with the Spanish began, the Aztecs had few allies. Cortes • 1485 –Cortes was born in in Medellin, Extremadura, Spain. His parents were of small Spanish nobility. • 1499, when Cortes was 14 he attended the University of Salamanca, at this university he studied law. • 1504 (19) he set sail for what is now the Dominican Republic to try his luck in the New World. • 1511, (26) he joined an army under the command of Spanish soldier named Diego Velázquez and played a part the conquest of Cuba. Velázquez became the governor of Cuba, and Cortes was elected Mayor-Judge of Santiago. • 1519 (34) Cortes expedition enters Mexico. • Aug. 13, 1521 15,000 Aztecs die in Cortes' final all-out attack on the city. -

Sin, Confession, and the Arts of Book- and Cord-Keeping: an Intercontinental and Transcultural Exploration of Accounting and Governmentality

Sin, Confession, and the Arts of Book- and Cord-Keeping: An Intercontinental and Transcultural Exploration of Accounting and Governmentality The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Urton, Gary. 2009. Sin, confession, and the arts of book- and cord- keeping: An intercontinental and transcultural exploration of accounting and governmentality. Comparative Studies in Society and History 51(4): 801–831. Published Version doi:10.1017/S0010417509990144 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:3716616 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Comparative Studies in Society and History 2009;51(4):801–831. 0010-4175/09 $15.00 # Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History, 2009 doi:10.1017/S0010417509990144 Sin, Confession, and the Arts of Book- and Cord-Keeping: An Intercontinental and Transcultural Exploration of Accounting and Governmentality GARY URTON Harvard University INTRODUCTION My objective is to examine an intriguing and heretofore unrecognized conver- gence in the history of bookkeeping. The story revolves around an extraordi- nary parallelism in the evolution of bookkeeping and the philosophical and ethical principles underlying the practice of accounting between southern Europe and Andean South America during the two centuries or so prior to the Spanish invasion of the Inka Empire in 1532. The event of the European invasion of the Andes brought these two similar yet distinct trans-Atlantic tra- ditions of “bookkeeping” and accounting into violent confrontation. -

Measuring the Passage of Time in Inca and Early Spanish Peru Kerstin Nowack Universität Bonn, Germany

Measuring the Passage of Time in Inca and Early Spanish Peru Kerstin Nowack Universität Bonn, Germany Abstract: In legal proceedings from 16th century viceroyalty of Peru, indigenous witnesses identified themselves according to the convention of Spanish judicial system by name, place of residence and age. This last category often proved to be difficult. Witnesses claimed that they did not know their age or gave an approximate age using rounded decimal numbers. At the moment of the Spanish invasion, people in the Andes followed the progress of time during the year by observing the course of the sun and the lunar cycle, but they were not interested in measuring time spans beyond the year. The opposite is true for the Spanish invaders. The documents where the witnesses testified were dated precisely using counting years from a date in the distant past, the birth year of the founder of the Christian religion. But this precision in the written record perhaps distorts the reality of everyday Spanish practices. In daily life, Spaniards often measured time in a reference system similar to that used by the Andeans, dividing the past in relation to public events like a war or personal turning points like the birth of a child. In the administrative and legal area, official Spanish dating prevailed, and Andean people were forced to adapt to this novel practice. This paper intends to contrast the Andean and Spanish ways of measuring the past, but will also focus on the possible areas of overlap between both practices. Finally, it will be asked how Andeans reacted to and interacted with Spanish dating and time measuring. -

Proquest Dissertations

Andean caravans: An ethnoarchaeology Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nielsen, Axel Emil Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 13:00:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289098 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis arxl dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, cotored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print Ueedthrough. sut)standard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauttwrized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, t>eginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have t)een reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are availat>le fbr any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. -

Session Abstracts

THE INCAS AND THEIR ORIGINS SESSION ABSTRACTS Most sessions focus on a particular region and time period. The session abstracts below serve to set out the issues to be debated in each session. In particular, the abstract aims to outline to each discipline what perspectives and insights the other disciplines can bring to bear on that same topic. A session abstract tends to consist more of questions than answers, then. These are the questions that it would be useful for all participants to be thinking about in advance, so as to be ready to join in the debate on any session. And if you are the speaker giving a synopsis for that session, you may wish to start from the abstract as a guide to how to develop these questions, so as best to provoke the cross-disciplinary debate. DAY 1: TAWANTINSUYU: ITS NATURE AND IMPACTS A1. GENERAL PERSPECTIVES FROM THE VARIOUS DISCIPLINES This opening session serves to introduce the various sources of data on the past which together can contribute to a holistic understanding of the Incas and their origins. It serves as the opportunity for each of the various academic disciplines involved to introduce itself briefly to all the others, and for their benefit. The synopses for this session should give just a general outline of the main types of evidence that each discipline uses to come to its conclusions about the Inca past. What is it, within each of their different records of the past, that allows the archaeologist, linguist, ethnohistorian or geneticist to draw inferences as to the nature and strength of Inca control and impacts in different regions? In particular, how can they ‘reconstruct’ resettlements and other population movements within Tawantinsuyu? Also crucial — especially because specialists in other disciplines are not in a position to judge this for themselves — is to clarify how reliable are the main findings and claims that each discipline makes about the Incas. -

Farkındalık Ekonomisi- Ekonomik Farkındalık, Bireyselleşmiş Ekonomi * M

Türk Dünyası Uygulama ve Araştırma Merkezi Yenidoğan Dergisi No. 2018/2 Yorum M. A. Akşit Koleksiyonundan 6 Farkındalık Ekonomisi- Ekonomik Farkındalık, Bireyselleşmiş Ekonomi * M. Arif Akşit**, Eda Sayar ***, Mustafa Uçkaç**** *Eskişehir Acıbadem Hastanesinde Ekonomi Üzerine bir söyleşiden alınmıştır. **Prof. Dr. Pediatri, Neonatoloji ve Ped. Genetik Uzmanı, Acıbadem Hast., Eskişehir ***Uluslararası Hasta Hizmetleri, İngilizce İktisat Uzmanı, Acıbadem Hastanesi., Eskişehir ****Serbest Muhasebeci, Mali Müşavir, Mali Müşavir, İşletme Bilim Uzmanı, Eskişehir Yaşamak için yemek ile yemek için yaşamak ikilem olmamalı, ekonomi boyutunda irdelenmelidir, iki farklı boyut, birey temelinde, onun arzu ve isteğinin ötesinde, sağlığı boyutunda, bütünleştirilmeli ve anlamlandırılmalıdır. Yiyeceğin, yeterli ve etkin olması onun beğeni boyutunu kaldırmaz, onu diyet/ilaç boyutuna aldırmamalı, bireye özgün bir yapılanma yapılmalıdır. Ekonominin 3 temel “E” ilkesi; Effectiveness: etkinlik, Efficiency: verimlilik ve Eligibility: olabilirlik/bulunabilirlik olarak ele alındığında, sizin sahip olduğunuz varlık değil, sizin değer yarattığınız öne çıkmaktadır. Bir kişiye verdiğiniz gül sizin için gereksiz ve anlamsız bir harcama olabilir ama eğer karşısında olumlu etki yaratıyorsa, mutluluk oluşturuyorsa, para ile elde edilemeyen bir değer, ekonomik boyutu da olmaktadır. Sorunlu, kusurlu ve engelli olan bireylere harcama yapmaktansa sağlıklı olan kişilere yapılacak harcama daha ekonomik anlamda görülebilir, gelişmeye ancak sağlıklı olanların katkıda bulunabileceği -

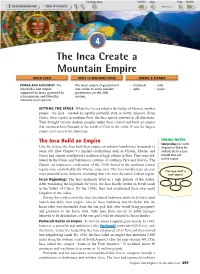

The Inca Create a Mountain Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES

4 The Inca Create a Mountain Empire MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES POWER AND AUTHORITY The The Incan system of government •Pachacuti •mita Inca built a vast empire was similar to some socialist • ayllu • quipu supported by taxes, governed by governments in the 20th a bureaucracy, and linked by century. extensive road systems. SETTING THE STAGE While the Aztecs ruled in the Valley of Mexico, another people—the Inca—created an equally powerful state in South America. From Cuzco, their capital in southern Peru, the Inca spread outward in all directions. They brought various Andean peoples under their control and built an empire that stretched from Ecuador in the north to Chile in the south. It was the largest empire ever seen in the Americas. The Inca Build an Empire TAKING NOTES Categorizing Use a web Like the Aztecs, the Inca built their empire on cultural foundations thousands of diagram to identify the years old. (See Chapter 9.) Ancient civilizations such as Chavín, Moche, and methods the Inca used Nazca had already established a tradition of high culture in Peru. They were fol- to build their vast, lowed by the Huari and Tiahuanaco cultures of southern Peru and Bolivia. The unified empire. Chimú, an impressive civilization of the 1300s based in the northern coastal region once controlled by the Moche, came next. The Inca would create an even The Inca built a more powerful state, however, extending their rule over the entire Andean region. vast empire. Incan Beginnings The Inca originally lived in a high plateau of the Andes. -

Culture and Breastfeeding Duration in Peru and Bolivia

Culture and Breastfeeding duration in Peru and Bolivia Juliano Assun¸c~ao∗ Soraya Rom´any June 24, 2019 Abstract In this paper, we study the effect of ethnic beliefs/preferences on breastfeeding practices in Peru and Bolivia. Comparing the breastfeeding practices of rural-to-urban migrants living in the same location by their ethnicity, we find Aymara mothers breastfeed longer than Quechua and Non-indigenous mothers. This is consistent with anthropological studies on Andean culture (Quechua and Aymara ethnic groups). The breastfeed- ing difference remains significant for urban children with an Aymara grandmother or Aymara great grandparents, and it increases with the presence of an additional child- bearing-age woman in the household. Furthermore, using geographic information and 1830's population statistics, we find that places with higher Indigenous-Spanish colony interaction are correlated with larger current breastfeeding differences. Keywords: breastfeeding behaviour, cultural traits, rural-to-urban migrants JEL Codes: I12, Z13 ∗PUC-Rio yUPB 1 Introduction Growing empirical evidence shows that culture plays a role in the determination of human behaviour. The evidence is based on the study of populations of immigrants and their descendants, who behave differently in a common economic and institutional context because of their inherited values and social beliefs (See Fern´andez(2010); Alesina and Giuliano(2015) for literature review). As recent examples we can mention the paper of Atkin(2016) on tastes and nutrition in India, and the paper of Christopoulou and Lillard(2015) on smoking behaviour in immigrants. The former attempts to quantify the effect of tastes on the family caloric intake. The latter addresses the importance of cultural dynamics on smoking, which is part of a group of economic behaviours that may be influenced by global cultural tendencies. -

Dates and Events

Dates and events 1898-99 Liberal Party comes to power; rise of tin mining 1899 Federal War 1932-35 Chaco War; Bolivia defeated by Paraguay 1942 Massacre at Catavi mine kills more than 40 people 1943-46 Military- MNR reformist government 1946-52 Extreme right-wing rule c. 1000 AD Aymara empire of Tiawanaku at its 1952 Revolution: MNR brought to power by height mass uprising; foundation of the COB; c. 1200 Collapse of Tiawanaku empire universal suffrage; nationalisation of major mines 1200-1450 Aymara kingdoms 1953 Agrarian Reform 1450 Inca invasion 1956 IMF 'stabilisation' plan 1532 Spanish conquest of Andes begins 1964-78 Military rule 1538 Discovery of silver in Potosi 1967 New Constitution (still in use) 1781-83 Rebellion of Tupaj Katari and Tupaj Amaru threatens Spanish control of Alto 1970 Teoponte guerrilla force defeated. Peru Juan Jose Torres takes power. 1809 Revolt against the Spanish, La Paz 1971 Hugo Banzer leads military coup 1825 Independence, 6 August 1974 Banzer consolidates his power 1879-83 War of the Pacific. Chile takes coastal 1978-82 Political chaos; three general provinces and Bolivia loses outlet to the sea elections; various military coups 1884-98 Silver-mining oligarchy rules through 1980 'Narco-coup' by Garcia Meza and Arce the Conservative Party Gomez 86 BOLIVIA 1982-85 Siles Zuazo (Union Democrdtica y 1990 First March for Territory, Dignity, and life Popular) President by lowland indigenous people 1985 World-record hyperinflation (22,000 per 1992 Free-trade zone at Ilo (Pacific Coast) cent per annum) instituted -

Ethnomathematics of the Inkas

Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York 2008 10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_8647 Helaine Selin Ethnomathematics of the Inkas Thomas E. Gilsdorf Without Abstract Under the shade of a tree some women are sitting. They are watching over several children, but at the same time their bodies are subtly swaying and their hands are busy moving threads. These women are weaving. As they talk among themselves, calculations are occurring: 40 × 2, 20 × 2, 10 × 2, etc. On their weaving tools symmetric patterns of geometric and animal figures are slowing emerging, produced from years of experience in counting and understanding symmetric properties. The procedures they follow have been instructed to them verbally as has been done for thousands of years, and they follow it precisely, almost subconsciously. In fact, these women are doing mathematics. They are calculating pairs of threads in blocks of tens (10, 20, and so on) and determining which colors of threads must go in which places so that half of emerging figures will be exactly copied across an axis of symmetry. These women, and likely some girls who are learning from them, are not writing down equations or scratching out the calculations on a notepad. Remarkably, the weaving is done from memory. Weaving has existed in most cultures around the world, so the events and hence the mathematics in the previous paragraph could occur almost anywhere. In our case, we are going to consider the mathematics of the South American cultural group of the Quechua‐speaking Inkas (Incas).