Conference on Education for Sustainable Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14Th August 2019)

Post Examination Version (14th August 2019) © Tim Smart Contents CONTENTS MAPS AND TABLES 1 This document . 4 Map 1 Neighbourhood plan boundary . 7 Map 2 Character areas . 10 2 Executive summary . 5 Map 3 Land use . 12 3 Background . 6 Map 4 Transport network . 13 4 Meeting the basic conditions . 8 Map 5 Boscombe and Pokesdown Neighbourhood Plan Proposals . 34 5 Map 6 Existing conservation areas and listed buildings . 38 About our area: Character areas . 14 Map 7 Existing open spaces. .. 52 6 Our vision, aims and objectives . 28 Map 8 Licensed HMOs . 71 Map 9 Retail zones . 81 7 Our policies – Heritage . 36 Table 1 Population and households 2001 . 55 8 Our policies – Housing . 54 Table 2 Population and households 2011 . 55 9 Our policies – Work, shops and services . 74 Table 3 Population density . .. 56 Table 4 Population density Bournemouth and England, 10 Our policies – Site Allocations . .. 88 London, Camden (for comparison) . .. 56 11 Projects, implementation and monitoring . .. 94-103 Table 5 Change in accommodation type 2001-2011. 57 12 Appendix I: Basic Conditions Statement . 104-112 Table 6 Change in accommodation type 2001-2011 Bournemouth 13 and England . 57 Appendix II: All policies . .. 124-128 Table 7 Person per room (households) . .. 59 Table 2 (from SHMA) Projected Household Growth, 2012-based Household Projections (2013-2033) . 63 Table 3 (from SHMA) Projected Household Growth 2013-33 – 2012-based SNPP with 2012-based Household Formation Rates . 63 Table 8 Estimated dwelling requirement by number of bedrooms (2013-2033) – Market Sector . 65 Table 9 Number of bedrooms in dwellings built in Boscombe East . -

Local Election Wards

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Bournemouth, Christchurch & Poole Council Election of Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Councillor for Alderney & Bourne Valley Reason why no Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) longer nominated* CRESCENT (Address in Bournemouth, Alliance for Local Living Claire Leila Christchurch & Poole) Independent Candidate. CRYANS 5 Norman Avenue, Poole, UK Independence Party Joe BH12 1JH (UKIP) JOHNSON 123A Alma Road, Liberal Democrats Toby William Bournemouth, BH9 1AE LAND 9 Astbury Avenue, Poole, Labour Party Henry David BH12 5DT LEVY 58 Benbow Crescent, Poole, The Conservative Party Benjamin BH12 5AJ Candidate MAIDMENT 19 Loewy Crescent, Poole, Liberal Democrats Rachel Marie BH12 4PQ NORTON 112 Melbury Avenue, Poole, Poole People - independent Benjamin BH12 4EW and local SMALLEY (Address in Bournemouth, Independent Martin David Christchurch & Poole) STOKES 80 Bradpole Road, Labour Party David Llewellyn Bournemouth, BH8 9NZ Kelsey TRENT 55 Fraser Road, Wallisdown, Liberal Democrats Tony Poole, Dorset, BH12 5AY WATTS 197 Fairmile Road, The Conservative Party Trevor Robert Christchurch, BH23 2LF Candidate WEIR (Address in Bournemouth, Labour Party Lisa Jane Christchurch & Poole) WELCH 42 Roslin Road South, The Conservative Party Gregory Stanley Bournemouth, BH3 7EG Candidate *Decision of the Returning Officer that the nomination is invalid or other reason why a person nominated no longer stands nominated. The persons above against whose name no entry -

Bournemouth East Profile

Appendix G - Bournemouth East Locality Overview The Bournemouth East locality is largely urban with a higher proportion of young people compared to the CCG average. The locality is relatively deprived compared to both local and national levels. Some housing increase will be seen in Boscombe West and East wards, if this planned development is completed. An analysis of health and the wider determinants of health highlights poor outcomes for overcrowding, hospital stays for self harm and alcohol related harm, emergency hospital admissions for hip fractures in the 65 and over age group and incidence of prostate cancer. The following headings have been used to describe the locality in more detail: • Demographics • Housing • Health and Wider Determinants Demographics Population ONS 2016 mid-year population estimates show that there are approximately 52,900 people living in the Bournemouth East locality (26,600 males and 26,300 females). In this urban area, population density is highest around Boscombe, Pokesdown and west Southbourne. Compared to the Dorset CCG average, Bournemouth East has a higher proportion of people aged 15-44, and a lower proportion of people aged 55 to 79. The proportion of the population aged 30-44 in Bournemouth East is higher than the national average (22% compared with 20%). Locally produced projections suggest that the population of the Bournemouth East locality will rise at a faster rate (+3%) than both the Dorset CCG average (+2%) and the national average (+2%) between 2018 and 2021. Within this trend, the proportion of the population aged 30- 44 will remain higher than the national average. -

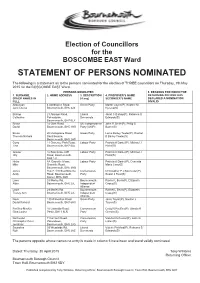

Statement of Persons Nominated

Election of Councillors for the BOSCOMBE EAST Ward STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED The following is a statement as to the persons nominated for the election of THREE Councillors on Thursday, 7th May 2015 for the BOSCOMBE EAST Ward. PERSONS NOMINATED 5. REASONS FOR WHICH THE 1. SURNAME, 2. HOME ADDRESS 3. DESCRIPTION 4. PROPOSER’S NAME RETURNING OFFICER HAS OTHER NAMES IN (if any) SECONDER’S NAME DECLARED A NOMINATION FULL INVALID Altounyan 4 Ashbourne Road, Green Party Martin Coyne(P), Kristine M Jane Louise Bournemouth, BH5 2JS Hyczka(S) Bishop 23 Abinger Road, Liberal Janet C Bishop(P), Rebecca S Catherine Pokesdown, Democrats Edwards(S) Bournemouth, BH7 6LX Brown 24 Glen Road, UK Independence John R Smith(P), Philip S David Bournemouth, BH5 1HR Party (UKIP) Bunce(S) Bruno 20 Livingstone Road, Green Party Lorna Bailey-Towler(P), Rachel Theresa Nichola Southbourne, B Bailey-Towler(S) Bournemouth, BH5 2AS Corry 11 Clarence Park Road, Labour Party Patricia A Daniel(P), Michael J Tina Bournemouth, BH7 6LE Hicks(S) Grower 16 Boscombe Cliff Labour Party Patricia A Daniel(P), Michael J Jilly Road, Bournemouth, Hicks(S) BH5 1JL Hicks 8A Granville Mews, Labour Party Patricia A Daniel(P), Concetta Mike Granville Road, Maria Corry(S) Bournemouth, BH5 2AQ Jones Flat 7, 110 Southbourne Conservative Christopher P J Rochester(P), Andy Road, Bournemouth, Party Susan J Field(S) Dorset, BH6 3QH Lowe 29 Morley Rd, Bournemouth Rachel L Bevis(P), Elizabeth Albie Bournemouth, BH5 2JL Independent Casey(S) Alliance Lowe 29 Morley Rd, Bournemouth Rachel L Bevis(P), -

Dorset LEP Growing Places Fund Boscombe Regeneration

Dorset LEP Growing Places Fund CASE STUDY Boscombe Regeneration Boscombe West has high long standing levels of deprivation. The latest census showed that things were getting worse and the gap between the most deprived part of Bournemouth and its surrounding areas was widening, with the heart of the ward - Boscombe Central – shown as one of the most deprived areas in the South West. The Dorset LEP Growing Places Fund allocated £1.5 million to Bournemouth Borough Council to facilitate the establishment of a Community Land Trust and to develop 11 affordable homes for local people (one of which was for people with restricted mobility) on a shared ownership basis. This along with recent initiatives is starting to make a difference and regeneration is beginning to make an impact, although the issues are complex and fundamental improvements will take a considerable period of time. The development of 11 affordable, low energy family homes is located at Gladstone Mews and was completed and handed over in August 2014. The Gladstone Mews development includes the added value of the inclusion of latest fire suppression systems, allotments and a community orchard. By the end of 2014, ten of the properties, including the home for mobility impaired, were under offer. The development was completed below budget, at a cost of £1,194,395, allowing £305,605 of Growing Places Fund money to be released for reinvestment in further projects. In addition to this, the project enabled European money to be secured for bringing forward the development of a refurbished Creative Industries Hub at Gladstone Mews, providing further enterprise support for the area. -

And Its Contents May Be Confidential, Privileged And/Or Otherwise Protected by Law

From: To: BCE Information Subject: FW: Conservative Party response - second stage - South West Date: 03 April 2012 11:32:10 Attachments: Conservative Party - cover letter - South West.pdf Conservative Party - second stage response - South West.pdf South West - Plymouth Herald advertisement.pdf eview Assistant Conservative Campaign Headquarters, 30 Millbank, London SW1P 4DP e: t: From: Sent: 03 April 2012 11:21 To: '[email protected]' Cc: Subject: Conservative Party response - second stage - South West To whom it may concern, Please find attached the Conservative Party’s response to the second consultation stage for the South West, sent on behalf of Roger Pratt CBE, the Party’s Boundary Review Manager. Yours sincerely, eview Assistant Conservative Campaign Headquarters, 30 Millbank, London SW1P 4DP e: t: This email and any attachments to it (the "Email") are intended for a specific recipient(s) and its contents may be confidential, privileged and/or otherwise protected by law. If you are not the intended recipient or have received this Email in error, please notify the sender immediately by telephone or email, and delete it from your records. You must not disclose, distribute, copy or otherwise use this Email. Please note that email is not a secure form of communication and that the Conservative Party ("the Party") is not responsible for loss arising from viruses contained in this Email nor any loss arising from its receipt or use. Any opinion expressed in this Email is not necessarily that of the Party and may be personal to the sender. Find out about Boris Johnson's 9 point plan for London: www.backboris2012.com/9pointplan Join us and help turn Britain around www.conservatives.com/join/ Promoted by Alan Mabbutt on behalf of the Conservative Party, both at 30 Millbank, London, SW1P 4DP This email was received from the INTERNET and scanned by the Government Secure Intranet anti-virus service supplied by Cable&Wireless Worldwide in partnership with MessageLabs. -

Bournemouth Performance Review 2019

2019 Bournemouth’s Performance Review Ambition 2020 1 4 2008 2008 2009 2010 Town Centre Vision Bournemouth Boscombe Spa Village Kinson Hub opened launched Air Festival launched Leisure Scheme library, housing office, completed children’s centre 2010 BH Live charitable trust launched events hospitality active 2014 2013 2012 2011 £1m visitor centre 20 year Customer Arts by the Sea Hengistbury Head Seafront Strategy contact centre Festival launched officially opened adopted opened 130,000 visitors in 2018 16,627 LEDs, 1000 lighting columns 1638 lit signs & bollards 2014 2015 2015 2016 Streetlighting MASH - Multi Agency Tricuro set up Seascape Homes replacement Safeguarding Hub short and long term care, and Property Ltd launched opened support to adults, carers as private sector landlord to and their families house homeless families £350m development completed £200m in £4m construction phase savings 2018 2017 2017 2017 Town Centre investment Alternate weeks Bournemouth and Poole Aspire Adoption Agency bin collections shared corporate services set up with introduced created Dorset County Council and Borough of Poole Vitality Index Trip Advisor 2018 2018 2018 2018 Planning consent for Pier Approach THE greenest Best UK Beach £150m Winter Gardens Phase 2 regeneration town in UK 5th best in Europe project completed South Coast UK Powerhouse Town of the Year 2019 2018 2018 Bournemouth in Christmas Tree Wonderland Property Development top 20 for growth developed - funding for 5 years and Inward investment 2 Bournemouth’s Performance Review 2019 1 Introduction Welcome to Bournemouth Council’s final performance review. In the past we have provided annual performance The performance and achievements celebrated updates, but this year as we enter a new era with over the following pages are presented under the formation of the BCP Council, we wanted the headings of Bournemouth’s ‘Ambition 2020’ to celebrate and reflect on our journey towards priorities: achieving the Council’s Ambition 2020 priorities. -

Hidden Dorset II Report Shining a Light on Local Needs and Inspiring Local Giving

Hidden Dorset II Report Shining a light on local needs and inspiring local giving Contents Foreword…………………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………… 3. About the Author……………………………………………………………………………………………………….……. 4. Methodology…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4. Some Definitions……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5. 1.0 County of Contrasts…………………………………………………………………………………………………... 8. 2.0 Health, Wellbeing and Mental Health……………………………………………………………………… 20. 3.0 Work, Education and Training………………………………………………………………………………….. 33. 4.0 Disadvantage and Poverty……………………………………………………………………………………….. 48. 5.0 Loneliness and Isolation…………………………………………………………………………………………… 67. Data Sources………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 75. 2 Foreword Welcome to the second edition of Hidden Dorset. Many of you may remember our first edition in 2015 which illustrated the deprivation existing in Dorset, exhibiting the need for community action and philanthropy. Our aim is that this edition of Hidden Dorset is more than just a report on how things are. We want it to form the basis of an ongoing commitment to understanding the needs and challenges in the county, to bring people together to tackle those needs and create a mechanism for tracking progress and demonstrating positive impact. We’ll be using Hidden Dorset to inform our strategy and improve our grant making, but we want it to have a wider purpose. Our aim is that it will help groups demonstrate the need for their projects, start conversations between donors and recipients, unite communities over a common purpose and bring together representatives from the private, public and voluntary sectors for the good of the county as a whole. We realise that this may take time, but we want to highlight that we see this report as a catalyst for action. To create Hidden Dorset we have brought together the latest available statistical data to produce a comprehensive document, available to view on our website at www.dorsetcommunityfoundation.org. -

Appendix A- Homes for Boscombe Strategy 15-20

Homes for Boscombe Strategy 2017-20 1 Foreword Bournemouth Borough Council are fully committed to the regeneration of Boscombe and recognise that housing is critical to effecting lasting change. This new Homes for Boscombe Strategy outlines the work that we believe needs to take place, working in partnership with the local community and our partner organisations. Boscombe has huge potential for positive change. We want to take the area’s best elements and use its potential to attract investment to create a new housing offer, whilst tackling the issues within the current housing stock, so that Boscombe becomes a better place for people to live, work and visit. There has been a lot of positive work that has taken place already over the last 5 years and we intend to build on that. We know we have much more work to do but, with local support we are committed to improving housing in Boscombe for the benefit of the whole community. Councillor Robert Lawton, Cabinet Member for Housing Living in Boscombe, I know it to be a vibrant, exciting place with stunning architecture, award winning parks and beaches and a strong, creative community. Whilst there is much to be proud of and significant progress has been made in addressing issues within the area, we know that there is still more to be done before we achieve our objective of a sustainable community in Boscombe. The Homes for Boscombe Strategy outlines the ongoing work that needs to take place to make Boscombe an even better place to live, work and visit as part of the wider regeneration programme. -

N:\Reports\...\2Bournemouth.Wp

Draft recommendations on the future electoral arrangements for Bournemouth Borough Council May 2001 LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND LOCAL GOVERNMENT COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND The Local Government Commission for England is an independent body set up by Parliament. Our task is to review and make recommendations to the Government on whether there should be changes to local authorities’ electoral arrangements. Members of the Commission are: Professor Malcolm Grant (Chairman) Professor Michael Clarke CBE (Deputy Chairman) Peter Brokenshire Kru Desai Pamela Gordon Robin Gray Robert Hughes CBE Barbara Stephens (Chief Executive) We are statutorily required to review periodically the electoral arrangements – such as the number of councillors representing electors in each area and the number and boundaries of wards and electoral divisions – of every principal local authority in England. In broad terms our objective is to ensure that the number of electors represented by each councillor in an area is as nearly as possible the same, taking into account local circumstances. We can recommend changes to ward boundaries, and the number of councillors and ward names. © Crown Copyright 2001 Applications for reproduction should be made to: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Copyright Unit. The mapping in this report is reproduced from OS mapping by the Local Government Commission for England with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution -

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council

What happens next? We have now completed our review of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council. October 2018 Summary Report The recommendations must now be approved by Parliament. A draft order - the legal document which brings The full report and detailed maps: into force our recommendations - will be laid in Parliament. consultation.lgbce.org.uk www.lgbce.org.uk Subject to parliamentary scrutiny, the new electoral arrangements will come into force at the local elections in @LGBCE May 2019. Our recommendations: The table lists all the wards we are proposing as part of our final recommendations along with the number of Bournemouth, Christchurch and voters in each ward. The table also shows the electoral variances for each of the proposed wards, which tells you how we have delivered electoral equality. Finally, the table includes electorate projections for 2023, so you Poole Council can see the impact of the recommendations for the future. Final recommendations on the new electoral arrangements Ward No. of No. of Variance Ward No. of No. of Variance Name: Cllrs: Electors per from Name: Cllrs: Electors per from Cllr (2023): Average % Cllr (2023): Average % Alderney & Bourne Valley 3 3,984 -2% Littledown & Iford 2 3,801 -7% Bearwood & Merley 3 4,029 -1% Moordown 2 3,829 -6% Boscombe East & 2 4,166 2% Mudeford, Stanpit & 2 4,253 4% Pokesdown West Highcliffe Boscombe West 2 4,119 1% Muscliff & Strouden 3 4,284 5% Park Bournemouth Central 2 4,239 4% Newtown & 3 4,402 8% Heatherlands Broadstone 2 4,417 8% Oakdale 2 4,258 4% Burton & Grange 2 3,863 -5% Parkstone 2 4,419 8% Canford Cliffs 2 4,276 5% Penn Hill 2 4,435 9% Who we are: Electoral review: Canford Heath 3 3,649 -10% Poole Town 3 3,840 -6% ■ The Local Government Boundary Commission for An electoral review examines and proposes new England is an independent body set up by Parliament. -

Bournemouth Coastal Area Plan

Dorset Coastal Community Team Connective Economic Plan: 2016 Bournemouth Coastal Area Plan The Bournemouth Coastal Area plan is a daughter document of the Dorset Coastal Community Team Connective Economic Plan and covers the coastal area of Bournemouth. This plan has been written by the Dorset Coastal Community Team with input from Dorset Coast Forum members. Dorset Coastal Community Team Connective Economic Plan Bournemouth Coastal Area Plan Key Information This document is linked to the Connecting Dorset Coastal Community Team Economic Plan and (Sections 1-4 can be found in this) 5. Local Area (Provide brief geographical description) Bournemouth is the largest coastal resort along the Dorset coast. It is situated between Christchurch in the east and Poole in the west with its coastline stretching from Sandbanks to Christchurch Harbour. Bournemouth is not only a gateway town to the Jurassic coast but has 7.5 miles of golden sandy beaches that are backed by gravel and sandy clay cliffs. These cliffs are cut by a number of chines which provide both a unique landscapes and a natural access to the beaches. With the largest stock of bed-space on the south coast and the many award winning Blue Flag beaches Bournemouth is the main reasons for over 70% of visits to the area. Bournemouth is also the location for the UK’s first Coastal Activity Park where an area is being developed for the provision of facilities and a range of beach and water based activities. There are two piers along its coastal area; Bournemouth Pier and Boscombe Pier. Bournemouth Pier is a real focal point at central beach where there are plans to develop a unique beach front and promenade experience.