Most Frequent Errors in Judo Uki Goshi Technique and the Existing Relations Among Them Analysed Through T-Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read PDF > Judo Technique: Kesa Gatame, Uki Goshi, Kata Guruma

[PDF] Judo technique: Kesa gatame, Uki goshi, Kata guruma, Tomoe nage, Tate shiho gatame, Kata gatame,... Judo technique: Kesa gatame, Uki goshi, Kata guruma, Tomoe nage, Tate shiho gatame, Kata gatame, Deashi harai, Ude hishigi ude gatame, O goshi Book Review These kinds of book is every thing and helped me hunting forward plus more. It is probably the most remarkable book we have read through. It is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding, once you begin to read the book. (Everet t St ant on) JUDO TECHNIQUE: KESA GATA ME, UKI GOSHI, KATA GURUMA , TOMOE NA GE, TATE SHIHO GATA ME, KATA GATA ME, DEA SHI HA RA I, UDE HISHIGI UDE GATA ME, O GOSHI - To save Judo technique: Kesa g atame, Uki g oshi, Kata g uruma, Tomoe nag e, Tate shiho g atame, Kata g atame, Deashi harai, Ude hishig i ude g atame, O g oshi PDF, make sure you refer to the link beneath and download the file or get access to additional information which are related to Judo technique: Kesa gatame, Uki goshi, Kata guruma, Tomoe nage, Tate shiho gatame, Kata gatame, Deashi harai, Ude hishigi ude gatame, O goshi book. » Download Judo technique: Kesa g atame, Uki g oshi, Kata g uruma, Tomoe nag e, Tate shiho g atame, Kata g atame, Deashi harai, Ude hishig i ude g atame, O g oshi PDF « Our online web service was released using a want to serve as a full online electronic catalogue that gives usage of large number of PDF guide assortment. -

Guide Nage No Kata

SOMMAIRE Qu’est ce que le Nage No Kata ? 4 Illustrations et commentaires du guide 5 Généralités sur le Nage No Kata 6 Le Nage No Kata 7 Tableau « le Nage No Kata et son intérêt pour la pratique du Judo » 24 Conclusion 28 Lexique 29 Planche Nage No Kata Ont participé à la réalisation de cet ouvrage : Michel Algisi : 7e dan, cadre technique, responsable national des katas Patrice Berthoux : 6e dan, cadre technique André Boutin : 7e dan, cadre technique Laurent Dosne : 5e dan, professeur de judo Michèle Lionnet : 6e dan, cadre technique, coordonnatrice de l’ouvrage André Parent : 5e dan, professeur de judo Louis Renelleau : 7e dan, professeur de judo Ce document a été validé par la Direction Technique Nationale et pour la Commission des Hauts Gradés : Frédérico Sanchis. L’ouvrage s’est inspiré de la cassette vidéo fédérale sur le Nage No Kata et des commentaires de Georges Beaudot. Il vient en complément de la planche du Nage No Kata (coopérative de documents FFJudo). Conception et réalisation - Boulogne-Billancourt - © FFJUDO Mars 2007 2 Crédit photo : D. Boulanger - Kodokan - D. Chowanek (Lines-Art) - R. Danis - DPPI. PRÉFACE Ce guide est destiné à tous les judokas, jeunes ou moins jeunes, qui souhaitent apprendre le Nage No Kata ou se perfectionner dans sa pratique. Le choix du format permettra à chacun de pouvoir le glisser facilement dans son sac de judo, et ainsi, l’avoir toujours à portée de main. Cet ouvrage, qui fait suite à la planche du Nage No Kata, vous apportera des précisions techniques et des conseils vous permettant de mieux effectuer le kata. -

JUDO Under the Authority of the Bakersfield Judo Club

JUDO Under the Authority of the Bakersfield Judo Club Time: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 6:30 -8:00 PM Location: CSUB Wrestling Room Instructors: Michael Flachmann (4th Dan) Phone: 661-654-2121 Steve Walsh (1st Dan) Guest Instructors: Dale Kinoshita (5th Dan) Phone: (work) 834-7570 (home) 837-0152 Brett Sakamoto (4th Dan) Gustavo Sanchez (1st Dan) The Bakersfield Judo Club rd meets twice a week on 23 St / Hwy 178 Mondays and Thursdays from 7:00 to 9:00 PM. JUDO Club They practice under the 2207 ‘N’ Authority of Kinya th 22nd St Sakamoto, Rokudan (6 Degree Black Belt), at 2207 N St. ’ St Q ‘N’ St ‘ Chester Ave Truxtun Ave Etiquette: Salutations: Pronunciation: Ritsurei Standing Bow a = ah (baa) Zarei Sitting Bow e = eh (kettle) Seiza Sitting on Knees i = e (key) o = oh (hole) When to Bow: u = oo (cool) Upon entering or exiting the dojo. Upon entering or exiting the tatami. Definitions: Before class begins and after class ends. Judo “The Gentle Way” Before and after working with a partner. Judoka Judo Practitioner Sensei Instructor Where to sit: Dojo Practice Hall Kamiza (Upper Seat) for senseis. Kiotsuke ATTENTION! Shimoza (Lower Seat) for students. Rei Command to Bow Joseki – Right side of Shimoza Randori Free practice Shimoseki – Left side of Shimoza Uchi Komi “Fitting in” or “turning in” practice Judo Gi: Students must learn the proper Tatami Judo mat way to war the gi and obi. Students should Kiai Yell also wear zoris when not on the mat. Hajime Begin Matte STOP! Kata Fromal Exercises Tori Person practicing Students must have technique Uke Person being their own personal practiced on health and injury O Big or Major insurance. -

WPB Judo Academy Parents and Judoka Handbook

WPB Judo Academy 2008 Parents and Judoka Handbook Nage-Waza - Throwing Techniques O-soto-otoshi O-soto-gari Ippon-seio-nage De-ashi-barai Tai-otoshi Major Outer Drop Major Outer One Arm Shoulder Advancing Foot Body Drop Throw Sweep O-uchi-gari Ko-uchi-gari Ko-uchi-gake Ko-soto-gake Ko-soto-gari Major Inner Reaping Minor Inner Reaping Minor Inner Hook Minor Outer Hook Minor Outer Reap Uki-goshi O-goshi Tsuri-goshi Floating Hip Throw Major Hip Throw Lifting Hip Throw Osae-Waza - Holding Techniques Kesa-gatame Yoko-shiho-gatame Kuzure-kesa-gatme Scarf Hold Side 4 Quarters Broken Scarf Hold Nage-Waza - Throwing Techniques Morote-seio-nage O-goshi Uki-goshi Tsuri-goshi Koshi-guruma Two Arm Shoulder Major Hip Throw Floating Hip Throw Lifting Hip Throw Hip Whirl Throw Sode-tsuri-komi-goshi Tsuri-komi-goshi Sasae-tsuri-komi-ashi Tsubame-gaeshi Okuri-ashi-barai Sleeve Lifting Pulling Lifting Pulling Hip Lifting Pulling Ankle Swallow’s Counter Following Foot Hip Throw Throw Block Sweep Shime-Waza - Strangulations Nami-juji-jime Normal Cross Choke Ko-soto-gake Ko-soto-gari Ko-uchi-gari Ko-uchi-gake Minor Outer Hook Minor Outer Reap Minor Inner Reap Minor Inner Hook Osae-Waza - Holding Techniques Kansetsu-Waza - Joint Locks Gyaku-juji-jime Reverse Cross Choke Kami-shiho-gatame Kuzure-kami-shiho-gatame Upper 4 Quarters Hold Broken Upper 4 Quarters Hold Ude-hishigi-juji-gatme Cross Arm Lock Tate-shiho-gatame Kata-juji-jime Mounted Hold Half Cross Choke Nage-Waza - Throwing Techniques Harai-goshi Kata-guruma Uki-otoshi Tsuri-komi-goshi Sode-tsuri-komi-goshi -

Junior First (1St) Degree – Yellow

Junior Fourth (4th) Degree – Orange Requirements (Minimum) Age – 7 Name __________________ Time in Previous Degree – 3 months Date Started ____________ Class Attendance – 24 classes Date Completed __________ Promotions Points – 7 points (see point calculation sheet) Previous Degree Requirements All of this Degree Requirements signed off by a Sensei General Information 1. Name the three divisions of standing techniques (Tachi Waza) in English and Japanese. Hand techniques – Te Waza Hip techniques – Koshi Waza Foot techniques – Ashi Waza 2. Name the three divisions of mat techniques (Ne Waza) in English and Japanese. Holding techniques – Osaekome Waza Choking techniques – Shime Waza Joint locking techniques – Kansetsu Waza 3. Name the two divisions of sacrifice techniques (Sutemi Waza) in English and Japanese. Back falling sacrifice techniques – Ma Sutemi Waza Side falling sacrifice techniques – Yoko Sutemi Waza 4. How can you help during Judo class? Judo Vocabulary 1. To Float = Uki 11. Entry methods into mat work = Hairi 2. Lower Prop = Sasae Kata 3. Lift = Tsuri 12. Fifth class (Kyu) Judo rank = Gokyu 4. Pull = Komi 13. Third degree black belt = Sandan 5. Defense (to an attack) = Bogyo 14. Floating hip throw = Uki Goshi 6. Escape (from a hold down) = Fusegi 15. Foot stop throw (Lower Prop Lift Pull 7. Back falls = Koho Ukemi Foot) = Sasae Tsuri Komi Ashi 8. Front falls = Zempo Ukemi 16. Sweeping hip throw = Harai goshi 9. Decision! (referee’s call for judges decision) = 17. Modified Side corners hold = Kuzure Hantei!! Yoko Shiho Gatame -

WD PG Kyu Grading Syllabus

Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus A Trail Form White Belt To Brown Belt Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus 5th Kyu YELLOW Belt KIHON (Basics) REI (Bow) Ritsu-rei: Standing bow Za-rei: Sitting bow SHISEI (Postions) Shizen-hon-tai: Basic natural guard (Migi/Hidari-shizen-tai: Right/Left) Jigo-hon-tai: Basic defensive guard (Migi/Hidari-jigo-tai: Right/Left) SHINTAI (walks, movements) Tsuri-ashi: Feet shuffling (in common with Ayumi-ashi, Tsugi-ashi and Tai-sabaki) Ayumi-ashi: Normal walk, “foot passes foot” (Mae/Ushiro: Forwards/Backwards) Tsugi-ashi: Walk “foot chases foot” (Mae/Ushiro, Migi/Hidari) Tai-sabaki: Pivot (90/180°, Mae-Migi/Hidari, Ushiro-Migi/Hidari); KUMI-KATA: Grips (Hon-Kumi-Kata, Basic grip, Migi/Hidari-K.-K., Right/Left) WAZA: Technique KUZUSHI, TSUKURI, KAKE: Unbalancing, Positioning, Throw (Phases of the techniques) HAPPO-NO-KUZUSHI: The eight directions of unbalancing UKEMI (Break-falls) Ushiro-ukemi: Backwards break-fall Yoko-ukemi: Side break-fall (Migi/Hidari-yoko-ukemi) Mae-ukemi: Forward break-fall Mae-mawari-ukemi: Rolling break-fall Zempo-kaiten-ukemi: Leaping rolling break-fall KEIKO (Training exercises) Uchi-komi: Repetitions of entrances (lifting) Butsukari: Repetitions of impacts (no lifting) Kakke-ai: Repetitions of throws Yakusoku-geiko: One technique each without any reaction from Uke Kakari-geiko: One attacking, the other defending using the gentle way Randori: Free training exercise Shiai: Competition fight 2 Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus NAGE-WAZA -

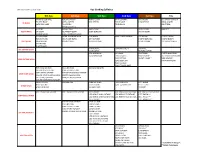

Kyu Grading Syllabus Summary

Western University Judo Club Kyu Grading Syllabus 5th Kyu 4th Kyu 3rd Kyu 2nd Kyu 1st Kyu Extra MOROTE SEOI NAGE KUCHIKI DAOSHI MOROTE GARI KATA GURUMA UKI OTOSHI UCHI MATA SUKASHI ERI SEOI NAGE KIBISU GAESHI SEOI OTOSHI SUKUI NAGE SUMI OTOSHI YAMA ARASHI TE WAZA KATA SEOI NAGE TAI OTOSHI TE GURUMA OBI OTOSHI IPPON SEOI NAGE O GOSHI HARAI GOSHI HANE GOSHI TSURI GOSHI DAKI AGE KOSHI WAZA UKI GOSHI TSURIKOMI GOSHI KOSHI GURUMA UTSURI GOSHI USHIRO GOSHI SODE TSURIKOMI GOSHI DE ASHI BARAI SASAE TSURIKOMI ASHI UCHI MATA ARAI TSURIKOMI ASHI O GURUMA O UCHI GAESHI HIZA GURUMA OKURI ASHI BARAI ASHI GURUMA O SOTO GURUMA O SOTO GAESHI ASHI WAZA KO UCHI GARI KO SOTO GARI O SOTO OTOSHI KO SOTO GAKE UCHI MATA GAESHI O UCHI GARI O SOTO GARI TOMOE NAGE HIKIKOMI GAESHI URA NAGE MA SUTEMI WAZA SUMI GAESHI TAWARA GAESHI UCHI MAKIKOMI UKI WAZA YOKO GAKE O SOTO MAKIKOMI SOTO MAKIKOMI TANI OTOSHI KANI BASAMI * UCHI MATA MAKIKOMI YOKO OTOSHI KAWAZU GAKE * DAKI WAKARE YOKO SUTEMI WAZA YOKO GURUMA HARAI MAKIKOMI YOKO WAKARE YOKO TOMOE NAGE HON KESA GATAME KATA GATAME SANKAKU GATAME KUZURE KESA GATAME KAMI SHIHO GATAME YOKO SHIHO GATAME KUZURE KAMI SHIHO GATAME OSAE KOMI WAZA KUZURE YOKO SHIHO GATAME USHIRO KESA GATAME TATE SHIHO GATAME MAKURA KESA GATAME KUZURE TATE SHIHO GATAME KATA JUJI JIME HADAKA JIME OKURI ERI JUME TSUKKOMI JIME RYO TE JIME NAMI JUJI JIME KATA HA JIME SODE GURUMA JIME KATA TE JIME SHIME WAZA GYAKU JUJI JIME SANKAKU JIME DO JIME * UDE HISHIGI JUJI GATAME UDE HISHIGI HARA GATAME UDE GARAMI UDE HISHIGI UDE GATAME UDE HISHIGI ASHI GATAME UDE -

Glossary of Judo Terms Relating to Techniques

GLOSSARY OF JUDO TERMS RELATING TO TECHNIQUES BODY PARTS Ashi Leg Ashi-waza Goshi Hip (also Koshi) O-goshi, Koshi-guruma Hiza Knee Hiza-garuma Kata Shoulder (or single) Kata-gatame Koshi Hip (also Goshi) Koshi-guruma Kubi Neck Kubi-kansetsu-waza (illegal) Mune Chest Mune-gatame Shiho Four quarters Yoko-shiho-gatame Tai Body Tai-otoshi Te Hand Te-garuma Tomoe Stomach Tomoe-nage Ude Arm Ude-garami Waki Armpit Waki-gatame KIT Eri Lapel Kata-eri-jime Obi Belt Obi-tsuri-goshi Sode Sleeve Sode-tsuri-komi-goshi ACTIONS Age Lift Daki-age (illegal) Daki Hug Daki-age (illegal) Gaeshi Counter (to throw) or trip Uchimata-gaeshi Gake Hook Ko-soto-gake Gari Reap O-soto-gari Garami Armlock or entanglement Ude-garami Gatame Hold or armlock Kesa-gatame Guruma Wheel Kata-guruma Gyaku/Gyaki Reverse (or Ushiro) Gyaku-kesa-garami Jime Strangle Hadaka-jime Kuzure Broken Kazure-yoko-shiho-gatame Ken ken Hopping Ken ken-uchimata Komi Drop or down Tsuri-komi-goshi Maki Winding Maki-komi Nage Throw Tomoe-nage Otoshi Drop Tai-otoshi Sukashi Sidestep Uchimata-sukashi Sutemi Sacrifice Sutemi-waza Uki Floating Uki-goshi Ushiro Reverse (or Gyaku) Ushiro-kesa-gatame Yoko Side Yoko-wakare Gaeshi Counter (to throw) or trip Uchimata-gaeshi OTHER Hidari Left Hidari-ashi-jime Hon Basic Hon-kesa-gatame Juji Cross Juji-jime Kami Upper Kami-shiho-gatame Kata Single (or shoulder) Kata-juji-jime Ko Minor Ko-ouchi-gari Migi Right Migi-ashi-jime O Major O-goshi Ryo Double Ryo-te-jime Soto Outer O-soto-gari Tate Lengthwise Tate-shiho-gatame Uchi Inner Uchi-mata Waza Technique Ne-waza . -

Seishin Judo Promotion Requirements

SEISHINJUDO AT SANDIA JUDO CLUB LINDA YIANNAKIS, 5TH DAN (USA-TKJ); 5TH DAN (USA JUDO) Requirements for Promotion The serious study of judo requires regular attendance, much persistence, an understanding of principles both physical and philosophical, and practice, practice, practice. Seishin Judo is committed to the study of the larger judo: judo as a way of life and a path as well as a powerful martial way. Classes focus on the principles that drive techniques and their application in various contexts. Students may advance in rank by meeting time in grade criteria and by demonstrating technical competence and theoretical and background knowledge. Randori, kata (formal and informal) and competition are the three main areas of judo application. Expectations and requirements in all three areas are stated at each grade level. In addition, attending clinics and seminars and providing supervised teaching (when appropriate) are required. Each test below includes a representative sampling of principles and techniques from judo. The tests do not represent a complete syllabus of judo. They also include techniques that are outside of the standard Kodokan program. This document is intended as a reference and study guide for the student. GOKYU (5th Kyu) Yellow Belt (All Testing is from Japanese Terminology) 1. Sound character and maturity 2. Minimum age of 14 years 3. Minimum time practicing Judo: 3 months 4. Regular dojo attendance 5. Good dojo hygiene 6. Good Judo/Jujutsu etiquette 7. Demonstrate competence in basic breakfalls 8. Demonstrate kiai and understanding of Judo spirit 9. Proper wearing and folding of the Judogi 10. Demonstrate standing and kneeling bows (ritsurei and zarei) 11. -

Midwest Academy Fundamentals Kihon Glossary

Midwest Academy of Martial Arts (630) 836 – 3600 Naperville, Il www.TheMidwestAcademy.com Seizan Ryu Kempo Jujutsu Fundamentals / Kihon English Japanese Positioning Tsukuri Notes Stances Shisei 1. Neutral stance 1. Chuitsu dachi 1. 2. Foundation stance 2. Kiso dachi 2. 3. Natural ready stance 3. Shizen yoi dachi 3. 4. Forward stance 4. Zenkutsu dachi 4. 5. Forward hook stance 5. Manji dachi 5. 6. Back stance 6. Kokutsu dachi 6. 7. Cat stance 7. Neko ashi dachi 7. 8. Crane Stance 8. Tsuru dachi 8. 9. Cross Stance 9. Juji dachi 9. 10. Hourglass Stance 10. Sunadokei dachi 10. 11. Pyramid 11. Shiho shisei 11. 12. Triangle/Offset triangle 12. Sankaku shisei 12. 13. Hurdler 13. Shogai shisei 13. Postures / Guards Kamae 1. Salutation Posture 1. Gassho gamae 1. 2. Standing attention posture 2. Kiritsu chumoku gamae 2. 3. Standing bow 3. Kiritsu rei 3. 4. Seated attention posture 4. Suwari chumoku gamae 4. 5. Seated bow 5. Suwari rei 5. 6. Meditation posture 6. Seiza gamae 6. 7. Fundamental posture 7. Kihon gamae 7. 8. High ready guard 8. Jodan yoi gamae 8. 9. Middle ready guard 9. Chudan yoi gamae 9. 10. Low ready guard 10. Gedan yoi gamae 10. 11. Single knee guard 11. Ippon hizamazuki gamae 11. Dodges Sorashi 1. Side dodge 1. Yoko sorashi 1. 2. Circular dodge 2. Marui sorashi 2. 3. Half Turn 3. Han tenkan 3. 4. Leg wave 4. Nami ashi 4. 5. Backwards dodge 5. Sorimi 5. 6. Pull in dodge 6. Hikimi 6. Footwork Ashi waza 1. Gliding step 1. -

Junior First (1St) Degree – Yellow

Junior Fifth (5th) Degree – Green Requirements (Minimum) Age – 8 Name __________________ Time in Previous Degree – 4 months Date Started ____________ Class Attendance – 32 classes Date Completed __________ Promotions Points – 8 points (see point calculation sheet) Previous Degree Requirements All of this Degree Requirements signed off by a Sensei General Information 1. List three of the seven men who attained 10th degree black belt while they were still alive? Nagaoka, Mifune, Yamashita, Isogai, Iizuka, Samura, Tornita 2. What is Kata? A formal prearranged practice routine 3. How many Kata are there in Kodokan Judo? Nine 4. Which Kata is considered most useful for learning throwing techniques? Nage no Kata 5. Which Kata is considered most useful for learning grappling techniques? Gatame no Kata Judo Vocabulary 1. Technique = Waza 13. Body = Tai 2. Hand Technique = Te Waza 14. Body movement = Shintai 3. Foot Technique = Ashi Waza 15. Pivoting or turning the body = Tai Sabaki 4. Holding Technique = Osaekomi Waza 16. To Drop = Otoshi 5. Counter Technique = Kaeshi Waza 17. Valley = Tani 6. Judo Uniform = Judogi 18. Forth degree black belt = Yodan 7. Judo Uniform Sleeve = Sode 19. Valley Drop = Tani Otoshi 8. Judo Uniform Belt = Obi 20. Floating drop = Uki Otoshi 9. Judo Practitioner or Player = Judoka 21. Body drop = Tai Otoshi 10. Practice hall for Judo = Dojo 22. Shoulder Wheel = Kata Guruma 11. Rolling = Kaiten 23. Shoulder hold = Kata Gatame 12. Front rolling falls = Zempo Kaiten Ukemi 24. Straddling hold = Tate Shiho Gatame Page 1 of -

What You Will Be Tested on for Each Rank

What you will be tested on for each rank White 1S Osoto Otoshi Ogoshi Yellow Osoto Otoshi Ogoshi Ippon Seoi Nage Osoto Gari Kesa Gatame Kuzure Kesa Gatame Yellow 1S Ippon Seoi Nage Osoto Gari Kesa Gatame Kuzure Kesa Gatame Tai otoshi Koshi Guruma Makura Kesa Gatame Ushiro Kesa Gatame Yellow 2S Tai otoshi Koshi Guruma Makura Kesa Gatame Ushiro Kesa Gatame Morote Seoi Nage Uki Goshi Yoko Shiho Gatame Kuzure Yoko Shihi Gatame Orange Morote Seoi Nage Uki Goshi Yoko Shiho Gatame Kuzure Yoko Shihi Gatame Ouchi Gari Hiza Guruma Kami Shiho Gatame Kazure Kami Shiho Gatame Orange 1S Ouchi Gari Hiza Guruma Kami Shiho Gatame Kazure Kami Shiho Gatame Kouchi Gari Sasae Tsurikomi Ashi Tate Shiho Gatame Kuzure Tate Shiho Gatame Orange 2S Kouchi Gari Sasae Tsurikomi Ashi Tate Shiho Gatame Kuzure Tate Shiho Gatame Tsurikomi Goshi Sode Tsurikomi Goshi Kata Gatame Green Tsurikomi Goshi Sode Tsurikomi Goshi Kata Gatame Harai Goshi Okuri Ashi Barai Hadaka Jime Green 1S Harai Goshi Okuri Ashi Barai Hadaka Jime Uchi Mata Deashi Barai Okuri Eri Jime Kata Ha Jime Green 2S Uchi Mata Deashi Barai Okuri Eri Jime Kata Ha Jime Kosoto Gari Harai Tsurikomi Ashi Ryote Jime Blue Kosoto Gari Harai Tsurikomi Ashi Ryote Jime Hane Goshi Ushiro Goshi Gyaku Juji Jime Nami Juji Jime Kata Juji Jime Blue 1S Hane Goshi Ushiro Goshi Gyaku Juji Jime Nami Juji Jime Kata Juji Jime Ashi Guruma Tomoe Nage Ashi Gatame Jime Sode Guruma Jime Blue 2S Ashi Guruma Tomoe Nage Ashi Gatame Jime Sode Guruma Jime Kata Guruma Oguruma Ude Gatame Purple Kata Guruma Oguruma Ude Gatame Uki Waza Yoko Guruma Juji Gatame Ude Garami Purple 1S Uki Waza Yoko Guruma Juji Gatame Ude Garami Soto Makikomi Yoko Otoshi Hiza Gatame Purple 2S Soto Makikomi Yoko Otoshi Hiza Gatame Sukui Nage Utsuri Goshi Waki Gatame Hara Gatame.