Devoir De Vigilance: Reforming Corporate Risk Engagement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

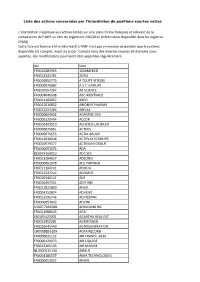

Liste Des Actions Concernées Par L'interdiction De Positions Courtes Nettes

Liste des actions concernées par l'interdiction de positions courtes nettes L’interdiction s’applique aux actions listées sur une plate-forme française et relevant de la compétence de l’AMF au titre du règlement 236/2012 (information disponible dans les registres ESMA). Cette liste est fournie à titre informatif. L'AMF n'est pas en mesure de garantir que le contenu disponible est complet, exact ou à jour. Compte tenu des diverses sources de données sous- jacentes, des modifications pourraient être apportées régulièrement. Isin Nom FR0010285965 1000MERCIS FR0013341781 2CRSI FR0010050773 A TOUTE VITESSE FR0000076887 A.S.T. GROUPE FR0010557264 AB SCIENCE FR0004040608 ABC ARBITRAGE FR0013185857 ABEO FR0012616852 ABIONYX PHARMA FR0012333284 ABIVAX FR0000064602 ACANTHE DEV. FR0000120404 ACCOR FR0010493510 ACHETER-LOUER.FR FR0000076861 ACTEOS FR0000076655 ACTIA GROUP FR0011038348 ACTIPLAY (GROUPE) FR0010979377 ACTIVIUM GROUP FR0000053076 ADA BE0974269012 ADC SIIC FR0013284627 ADEUNIS FR0000062978 ADL PARTNER FR0011184241 ADOCIA FR0013247244 ADOMOS FR0010340141 ADP FR0010457531 ADTHINK FR0012821890 ADUX FR0004152874 ADVENIS FR0013296746 ADVICENNE FR0000053043 ADVINI US00774B2088 AERKOMM INC FR0011908045 AG3I ES0105422002 AGARTHA REAL EST FR0013452281 AGRIPOWER FR0010641449 AGROGENERATION CH0008853209 AGTA RECORD FR0000031122 AIR FRANCE -KLM FR0000120073 AIR LIQUIDE FR0013285103 AIR MARINE NL0000235190 AIRBUS FR0004180537 AKKA TECHNOLOGIES FR0000053027 AKWEL FR0000060402 ALBIOMA FR0013258662 ALD FR0000054652 ALES GROUPE FR0000053324 ALPES (COMPAGNIE) -

Competition Policy

ISSN 1025-2266 COMPETITION POLICY NEWSLETTER EC COMPETITION POLICY NEWSLETTER Editors: 2008 Æ NUMBER 3 Inge Bernaerts Kevin Coates Published three times a year by the Thomas Deisenhofer Competition Directorate-General of the European Commission Address: European Commission, Also available online: J-70, 04/136 http://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/cpn/ Brussel B-1049 Bruxelles E-mail: [email protected] World Wide Web: http://ec.europa.eu/ competition/index_en.html I N S I D E : • The design of competition policy institutions for the 21st century by Philip Lowe • The new State aid General Block Exemption Regulation • The new Guidelines on the application of Article 81 of the EC Treaty to the maritime sector • The new settlement procedure in selected cartel cases • The CISAC decision • The Hellenic Shipyards decision: Limits to the application of Article 296 and indemnification provision in privatisation contracts MAIN DEVELOPMENTS ON • Antitrust — Cartels — Merger control — State aid control EUROPEAN COMMISSION Contents Articles 1 The design of competition policy institutions for the 21st century — the experience of the European Commission and DG Competition by Philip LOWE 12 The General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER): bigger, simpler and more economic by Harold NYSSENS 19 Rolling back regulation in the telecoms sector: a practical example by Ágnes SZARKA 25 The new Guidelines on the application of Article 81 of the EC Treaty to the maritime sector by Carsten BERMIG and Cyril RITTER 30 The new settlement procedure in selected -

IN TAX LEADERS WOMEN in TAX LEADERS | 4 AMERICAS Latin America

WOMEN IN TAX LEADERS THECOMPREHENSIVEGUIDE TO THE WORLD’S LEADING FEMALE TAX ADVISERS SIXTH EDITION IN ASSOCIATION WITH PUBLISHED BY WWW.INTERNATIONALTAXREVIEW.COM Contents 2 Introduction and methodology 8 Bouverie Street, London EC4Y 8AX, UK AMERICAS Tel: +44 20 7779 8308 4 Latin America: 30 Costa Rica Fax: +44 20 7779 8500 regional interview 30 Curaçao 8 United States: 30 Guatemala Editor, World Tax and World TP regional interview 30 Honduras Jonathan Moore 19 Argentina 31 Mexico Researchers 20 Brazil 31 Panama Lovy Mazodila 24 Canada 31 Peru Annabelle Thorpe 29 Chile 32 United States Jason Howard 30 Colombia 41 Venezuela Production editor ASIA-PACIFIC João Fernandes 43 Asia-Pacific: regional 58 Malaysia interview 59 New Zealand Business development team 52 Australia 60 Philippines Margaret Varela-Christie 53 Cambodia 61 Singapore Raquel Ipo 54 China 61 South Korea Managing director, LMG Research 55 Hong Kong SAR 62 Taiwan Tom St. Denis 56 India 62 Thailand 58 Indonesia 62 Vietnam © Euromoney Trading Limited, 2020. The copyright of all 58 Japan editorial matter appearing in this Review is reserved by the publisher. EUROPE, MIDDLE EAST & AFRICA 64 Africa: regional 101 Lithuania No matter contained herein may be reproduced, duplicated interview 101 Luxembourg or copied by any means without the prior consent of the 68 Central Europe: 102 Malta: Q&A holder of the copyright, requests for which should be regional interview 105 Malta addressed to the publisher. Although Euromoney Trading 72 Northern & 107 Netherlands Limited has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of this Southern Europe: 110 Norway publication, neither it nor any contributor can accept any regional interview 111 Poland legal responsibility whatsoever for consequences that may 86 Austria 112 Portugal arise from errors or omissions, or any opinions or advice 87 Belgium 115 Qatar given. -

Note D'information Etabli Par Conseillee Par En Reponse A

NOTE D’INFORMATION ETABLI PAR CONSEILLEE PAR EN REPONSE A L’OFFRE PUBLIQUE D’ACHAT VISANT LES ACTIONS ET LES OBLIGATIONS A OPTION DE CONVERSION ET/OU D’ECHANGE EN ACTIONS NOUVELLES OU EXISTANTES (OCEANES) DE CLUB MEDITERRANEE INITIEE PAR GAILLON INVEST AGISSANT DE CONCERT AVEC les personnes dénommées dans le corps de la présente note En application de l’article L. 621-8 du code monétaire et financier et de l’article 231-26 de son règlement général, l’Autorité des marchés financiers (l’« AMF ») a apposé le visa n° 13-363 en date du 15 juillet 2013 sur la présente note en réponse. Cette note en réponse a été établie par Club Méditerranée et engage la responsabilité de ses signataires. Le visa, conformément aux dispositions de l’article L. 621-8-1 I du code monétaire et financier, a été attribué après que l’AMF a vérifié « si le document est complet et compréhensible et si les informations qu’il contient sont cohérentes ». Il n’implique ni approbation de l’opportunité de l’opération, ni authentification des éléments comptables et financiers présentés. Avis important En application des dispositions des articles 231-19 et 261-1 I 2° et 5° du règlement général de l’AMF, le rapport du cabinet Accuracy, agissant en qualité d’expert indépendant, est inclus dans la présente note en réponse. La présente note en réponse est disponible sur les sites Internet de Club Méditerranée (www.clubmed- corporate.com) et de l’AMF (www.amf-france.org), et est mise gratuitement à disposition du public et peut être obtenue sans frais auprès de : Club Méditerranée Rothschild & Cie 11, rue de Cambrai 23bis, avenue de Messine 75019 Paris 75008 Paris Conformément aux dispositions de l’article 231-28 du règlement général de l’AMF, les autres informations relatives aux caractéristiques, notamment juridiques, financières et comptables de Club Méditerranée seront déposées auprès de l’AMF et mises à la disposition du public selon les mêmes modalités, au plus tard la veille du jour de l’ouverture de l’offre publique. -

2011 Registration Document Annual Financial Report SUMMARY

2011 Registration Document Annual Financial Report SUMMARY 1 PRESENTATION OF THE GROUP 3 6 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 227 1.1 Main key figures 4 6.1 Information about the Company 228 1.2 The Group’s strategy and general structure 5 6.2 Information about the share capital 232 1.3 Minerals 10 6.3 Shareholding 238 1.4 Minerals for Ceramics, Refractories, 6.4 Elements which could have an impact Abrasives & Foundry 17 in the event of a takeover bid 241 1.5 Performance & Filtration Minerals 26 6.5 Imerys stock exchange information 242 1.6 Pigments for Paper & Packaging 32 6.6 Dividends 244 1.7 Materials & Monolithics 36 6.7 Shareholder relations 244 1.8 Innovation 43 6.8 Parent company/subsidiaries organization 245 1.9 Sustainable Development 48 ORDINARY AND EXTRAORDINARY REPORTS ON THE FISCAL YEAR 2011 65 7 SHAREHOLDERS’ GENERAL MEETING 2 OF APRIL 26, 2012 247 2.1 Board of Directors’ management report 66 2.2 Statutory Auditors' Reports 77 7.1 Presentation of the resolutions by the Board of Directors 248 7.2 Agenda 254 7.3 Draft resolutions 255 3 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 83 3.1 Board of Directors 84 3.2 Executive Management 103 PERSONS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE 3.3 Compensation 105 8 REGISTRATION DOCUMENT AND THE AUDIT 3.4 Stock options 109 OF ACCOUNTS 261 3.5 Free shares 114 8.1 Person responsible for the Registration Document 262 3.6 Specific terms and restrictions applicable to grants 8.2 Certificate of the person responsible to the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer 116 for the Registration Document 262 3.7 Corporate officers’ transactions in securities -

2021 Indirect Tax Leaders Guide and May Not Be Used for Any Other Purpose

INDIRECT TAX LEADERS THECOMPREHENSIVEGUIDE TO THE WORLD’S LEADING INDIRECT TAX ADVISERS NINTH EDITION IN ASSOCIATION WITH PUBLISHED BY WWW.INTERNATIONALTAXREVIEW.COM BECOME PART OF THE ITR COMMUNITY. CONNECT WITH US TODAY. Facebook “Like” us on Facebook at www.facebook.com/internationaltaxreview f and connect with our editorial team and fellow readers. LinkedIn Join our group, International Tax Review, to meet your peers in and get incomparable market coverage. Twitter Follow us at @IntlTaxReview for exclusive research and t ranking insight, commentary, analysis and opinions. To subscribe, contact: Jack Avent Tel: +44 (0) 20 7779 8379 | Email: [email protected] www.internationaltaxreview.com Contents 2 Introduction and methodology 8 Bouverie Street, London EC4Y 8AX, UK Tel: +44 20 7779 8308 AMERICAS Fax: +44 20 7779 8500 Editor, World Tax and World TP 11 Argentina 18 Costa Rica Jonathan Moore 11 Bolivia 18 Ecuador 11 Brazil 19 Mexico Researchers 14 Canada 19 Peru Jason Howard Lovy Mazodila 17 Chile 20 United States Annabelle Thorpe 18 Colombia 21 Uruguay Production editor João Fernandes ASIA-PACIFIC Business development team 30 Australia 44 Philippines Margaret Varela-Christie 32 China 45 Singapore Raquel Ipo 32 Hong Kong SAR 46 South Korea Alexandra Strick 33 India 46 Sri Lanka Managing director, LMG Research 39 Indonesia 46 Taiwan Tom St. Denis 41 Japan 47 Thailand © Euromoney Trading Limited, 2020. The copyright of all 42 Malaysia 47 Vietnam editorial matter appearing in this Review is reserved by the 43 New Zealand publisher. No matter contained herein may be reproduced, duplicated EUROPE, MIDDLE EAST & AFRICA or copied by any means without the prior consent of the 63 Austria 77 Netherlands holder of the copyright, requests for which should be 63 Azerbaijan 80 Norway addressed to the publisher. -

Press Release 05.06.2021

PRESS RELEASE 05.06.2021 REPURCHASE OF OWN SHARES FOR ALLOCATION TO FREE SHARE GRANT PROGRAMS FOR THE BENEFIT OF EMPLOYEES Within the scope of its share repurchase program authorized by the April 22, 2021 shareholders' meeting (14th resolution), Kering has entrusted an investment service provider to acquire up to 200,000 ordinary Kering shares, representing close to 0.2% of its share capital as at April 15, 2021, no later than June 25, 2021 and subject to market conditions. These shares will be allocated to free share grant programs to some employees. The unit purchase price may not exceed the maximum set by the April 22, 2021 shareholders' meeting. As part of the previous repurchase announced on February 22, 2021 (with a deadline of April 16, 2021), Kering bought back 142,723 of its own shares. About Kering A global Luxury group, Kering manages the development of a series of renowned Houses in Fashion, Leather Goods, Jewelry and Watches: Gucci, Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen, Brioni, Boucheron, Pomellato, DoDo, Qeelin, Ulysse Nardin, Girard-Perregaux, as well as Kering Eyewear. By placing creativity at the heart of its strategy, Kering enables its Houses to set new limits in terms of their creative expression while crafting tomorrow’s Luxury in a sustainable and responsible way. We capture these beliefs in our signature: “Empowering Imagination”. In 2020, Kering had over 38,000 employees and revenue of €13.1 billion. Contacts Press Emilie Gargatte +33 (0)1 45 64 61 20 [email protected] Marie de Montreynaud +33 (0)1 45 64 62 53 [email protected] Analysts/investors Claire Roblet +33 (0)1 45 64 61 49 [email protected] Laura Levy +33 (0)1 45 64 60 45 [email protected] www.kering.com Twitter: @KeringGroup LinkedIn: Kering Instagram: @kering_official YouTube: KeringGroup Press release 05.06.2021 1/1 . -

EVALUATION of the RISKS of COLLECTIVE DOMINANCE in the AUDIT INDUSTRY in FRANCE Olivier Billard* Bredin Prat Marc Ivaldi* Toulou

EVALUATION OF THE RISKS OF COLLECTIVE DOMINANCE IN THE AUDIT INDUSTRY IN FRANCE Olivier Billard* Bredin Prat Marc Ivaldi* Toulouse School of Economics Sébastien Mitraille* Toulouse Business School (University of Toulouse) May 18, 2011 (revised June 7, 2012) Summary: The financial crisis drew attention to the crucial role of transparency and the independence of financial certification intermediaries, in particular, statutory auditors. Now any anticompetitive practice involving coordinated increases in prices or concomitant changes in quality that impacts financial information affects the effectiveness of this intermediation. It is therefore not surprising that the competitive analysis of the audit market is a critical factor in regulating financial systems, all the more so as this market is marked by various barriers to entry, such as the incompatibility of certification tasks with the preparation of financial statements or consulting, the expertise on (and the ability to apply) international standards for the presentation of financial information, the need to attract top young graduates, the prohibition of advertising, or the two-sided nature of this market where the quality of financial information results from the interaction between the reputation of auditors and audited firms. Against this backdrop, we propose a legal and economic study of the risks of collective dominance in the statutory audit market in France using the criteria set by Airtours case and, in particular, by analyzing how regulatory obligations incumbent on statutory auditors may favour the appearance of tacit collusion. Our analysis suggests that nothing prevents collective dominance of the auditors of the Big Four group in France to exist, which is potentially detrimental to the economy as a whole as the audit industry may fail to provide the optimal level of financial information. -

At the Centre of an Evolving Industrial World

REGISTRATION AT THE CENTRE DOCUMENT 2011 OF AN EVOLVING INDUSTRIAL WORLD CONTENT 5.6. Major projects 130 1 Group overview 5 5.7. Responsibility for chemicals 133 5.8. Health and Safety 136 1.1. Group profi le 6 5.9. Human Resources 142 1.2. Key fi gures/Comments on the fi nancial year 7 5.10. Assurance report by one of the Statutory 1.3. History and development of the Company 12 Auditors on a selection of environmental, social and safety indicators 151 2 Activities 15 2.1. Group structure 16 6 Financial statements 153 2.2. The Nickel Division 16 6.1. 2011 consolidated fi nancial statements 154 2.3. The Manganese Division 26 6.2. 2011 separate fi nancial statements 233 2.4. Alloys Division 39 6.3. Consolidated fi nancial statements for 2010 2.5. Organisational Structure of ERAMET SA/ and 2009 260 ERAMET Holding company 48 6.4. Dividend policy 260 2.6. Activity of the Divisions in 2011 49 6.5. Fees paid to the Statutory Auditors 261 2.7. Production sites, plant and equipment 51 2.8. Research and Development/Reserves and Resources 52 7 Corporate and 3 share-capital information 263 Risk factors 65 7.1. Market in the Company’s shares 264 3.1. Commodity risk 66 7.2. Share capital 268 3.2. Special relationships with Group partners 66 7.3. Company information 275 3.3. Mining and industrial risks 68 7.4. Shareholders’ agreements 279 3.4. Legal and tax risks/Disputes 71 3.5. Liquidity, market and counterparty risks 73 3.6. -

Bilan Carbone 2017 De L'oid

Bilan Carbone 2017 de l’OID Bilan Carbone 2017 de l’OID Sommaire Contexte & objectifs Cartographie des postes et sous-postes pris en compte Résultats du Bilan Carbone 2017 de l’OID Plan d’action A propos de l’OID Rédaction Note : Les annexes méthodologiques sont disponibles en téléchargement séparé. Contexte & objectifs A l’OID, nous accompagnons nos membres dans leurs démarches responsables, notamment sur l’amélioration de leur empreinte carbone. Il nous est donc apparu cohérent de nous lancer à notre tour dans l’évaluation de notre empreinte carbone, bien que n’étant pas soumis au Bilan GES Réglementaire. Si nous réalisons notre bilan pour la première fois, nous souhaitons renouveler l’exercice annuellement et ainsi évaluer la pertinence des actions mises en place. Les objectifs de cet exercice sont de mesurer nos émissions de gaz à effet de serre ; de hiérarchiser les postes les plus émissifs et de proposer des axes d’amélioration pour nourrir un plan d’actions et s’engager ainsi dans une démarche de réduction de nos émissions de gaz à effet de serre. Ce bilan aura été très riche en enseignements pour notre structure. En effet, il apparait clairement que la majorité des émissions de gaz à effet de serre de l’OID est due à son activité dématérialisée et à l’usage des outils numériques, reflet de notre cœur d’activité. Les déplacements comptent quant à eux pour une part minime de nos émissions. Cartographie des postes et sous-postes pris en compte 1 Juillet 2018 - OID Bilan Carbone 2017 de l’OID Résultats du Bilan Carbone 2017 de l’OID Les émissions 2017 de l’OID sont de 11,65 tCO2e. -

2019 Annual Report Annual 2019

a force for good. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2019 1, cours Ferdinand de Lesseps 92851 Rueil Malmaison Cedex – France Tel.: +33 1 47 16 35 00 Fax: +33 1 47 51 91 02 www.vinci.com VINCI.Group 2019 ANNUAL REPORT VINCI @VINCI CONTENTS 1 P r o l e 2 Album 10 Interview with the Chairman and CEO 12 Corporate governance 14 Direction and strategy 18 Stock market and shareholder base 22 Sustainable development 32 CONCESSIONS 34 VINCI Autoroutes 48 VINCI Airports 62 Other concessions 64 – VINCI Highways 68 – VINCI Railways 70 – VINCI Stadium 72 CONTRACTING 74 VINCI Energies 88 Eurovia 102 VINCI Construction 118 VINCI Immobilier 121 GENERAL & FINANCIAL ELEMENTS 122 Report of the Board of Directors 270 Report of the Lead Director and the Vice-Chairman of the Board of Directors 272 Consolidated nancial statements This universal registration document was filed on 2 March 2020 with the Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF, the French securities regulator), as competent authority 349 Parent company nancial statements under Regulation (EU) 2017/1129, without prior approval pursuant to Article 9 of the 367 Special report of the Statutory Auditors on said regulation. The universal registration document may be used for the purposes of an offer to the regulated agreements public of securities or the admission of securities to trading on a regulated market if accompanied by a prospectus or securities note as well as a summary of all 368 Persons responsible for the universal registration document amendments, if any, made to the universal registration document. The set of documents thus formed is approved by the AMF in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2017/1129. -

GROUPE ADP LAUNCHES the FIRST TRIAL of AUTONOMOUS SHUTTLES at a FRENCH AIRPORT (Pdf)

PRESS RELEASE 4 april 2018 Groupe ADP launches the first trial of autonomous shuttles at a French airport Groupe ADP has just launched a trial of two fully electric, driverless shuttles – the first at a French airport. Located in the heart of the airport's business district, Roissypôle, they connect the suburban train station (RER) to the Environmental and Sustainable Development Resource Centre and Groupe ADP's headquarters. Keolis, the operator, has joined forces with Navya, the French autonomous shuttle designer, to carry out the pilot project until July 2018. This initial trial represents an important milestone in Groupe ADP’s strategy to become a key player in the autonomous vehicle ecosystem. The itinerary of the two shuttles is unprecedented and presents great complexity: the aim is to test how the automated vehicles will behave on a high-traffic roadway, as well as how they merge and pass within an extremely dense environment that includes many pedestrians. An intelligent road infrastructure system that uses traffic signals to communicate dynamically with the shuttles has been set up, a world first, in order to optimise the crossing of the road in complete safety. Feedback from users (employees and passengers) is also one of the trial's determining factors. The airport city: a key area for the development of autonomous vehicles The new autonomous mobility solutions are a strategic concern for the development and competitiveness of our airports, as they help enhance service quality and the reliability of the various transportation modes used, in addition to improving road network flow around major hubs.