Po!Ities and Ideology in Late Medieval Cordoba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ated in Specific Areas of Spain and Measures to Control The

No L 352/ 112 Official Journal of the European Communities 31 . 12. 94 COMMISSION DECISION of 21 December 1994 derogating from prohibitions relating to African swine fever for certain areas in Spain and repealing Council Decision 89/21/EEC (94/887/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, contamination or recontamination of pig holdings situ ated in specific areas of Spain and measures to control the movement of pigs and pigmeat from special areas ; like Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European wise it is necessary to recognize the measures put in place Community, by the Spanish authorities ; Having regard to Council Directive 64/432/EEC of 26 June 1964 on animal health problems affecting intra Community trade in bovine animals and swine (') as last Whereas it is the objective within the eradication amended by Directive 94/42/EC (2) ; and in particular programme adopted by Commission Decision 94/879/EC Article 9a thereof, of 21 December 1994 approving the programme for the eradication and surveillance of African swine fever presented by Spain and fixing the level of the Commu Having regard to Council Directive 72/461 /EEC of 12 nity financial contribution (9) to eliminate African swine December 1972 on animal health problems affecting fever from the remaining infected areas of Spain ; intra-Community trade in fresh meat (3) as last amended by Directive 92/ 1 18/EEC (4) and in particular Article 8a thereof, Whereas a semi-extensive pig husbandry system is used in certain parts of Spain and named 'montanera' ; whereas -

History of a Guerilla Band: the Three Jubiles Brothers

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright History of a Guerilla Band: The three Jubiles brothers Antonio Téllez Solà January 2000 The three Jubiles brothers took to the hills in late March1939 and marauded through the hills around Villaviciosa, Almodóvar and Hornachuelos, before settling in the Montoro highlands. The Bujalance district of Córdoba province, where theCNT predominated, happened by a freak to escape the army’s Rising on 18 July 1936. In Bujalance the Civil Guard confined itself to staying in barracks and never lifted a finger, in spite of pres- sures from local rightists doubtless afraid of the power of the anarcho-syndicalist labour organisation. In the end, on 25 July, Antonio Téllez Solà the Civil Guard placed itself at the disposition of the Popular History of a Guerilla Band: The three Jubiles brothers Front. The garrison was shipped out to Jaén or to Madrid, ex- January 2000 cept for one sergeant and two Guards accused of having imple- Retrieved on 17th May 2021 from mented the ley de fugas (shooting ‘escaping’ prisoners) in the www.katesharpleylibrary.net Cañetejo ravine back in December 1933; these were executed Published in Polémica (Barcelona), no. 70, January 2000. in Cañetejo on 25 July. Translated by: Paul Sharkey. From the very outset, a Popular Front was established: it was made up of nine members, three of them from the CNT: usa.anarchistlibraries.net these were Francisco Garcia Cabello (aka El Niño del Aceite) who had been sentenced to death following the revolutionary events of December 1933, Bartolomé Parrodo Serrano and Ilde- fonso Coca Chocero (aka El Viejo). -

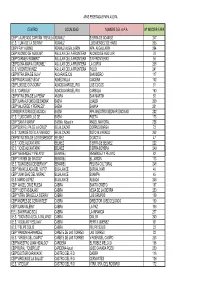

Centro Localidad Nombre Del Apa Nº

APAS FEDERADAS FAPA AGORA CENTRO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DEL A.P.A. Nº INSCRIP.FAPA CEIP "LAUREADO CAPITÁN TREVILLA"ADAMUZ SIERRA DE ADAMUZ 247 I.E.S. "LUNA DE LA SIERRA" ADAMUZ LUIS MENDEZ DE HARO 206 CEIP FRAY ALBINO ADAMUZ-ALGALLARIN APA ALGALLARIN 294 CEIP"ALONSO DE AGUILAR" AGUILAR DE LA FRONTERA ALONSO DE AGUILAR 79 CEIP"CARMEN ROMERO" AGUILAR DE LA FRONTERA SIN FRONTERAS 56 CEIP"DOÑA MARIA CORONEL" AGUILAR DE LA FRONTERA LA CURVA 208 I.E.S. VICENTE NUÑEZ AGUILAR DE LA FRONTERA POLEY 241 CEIP"NTRA.SRA.DE GUIA" ALCARACEJOS SAN ISIDRO 117 CEIP"RODRIGUEZ VEGA" ALMEDINILLA CAICENA 102 CEIP"LUIS DE GONGORA" ALMODOVAR DEL RIO LOS CUCOS 91 I.E.S. "CARBULA" ALMODOVAR DEL RIO CARBULA 160 CEIP"NTRA.SRA.DE LA PEÑA" AÑORA SAN MARTIN 93 CEIP"JUAN ALFONSO DE BAENA" BAENA JUALBA 209 CEIP"VALVERDE Y PERALES" BAENA BAIANA 201 CONSERVATORIO DE MÚSICA BAENA APA MAESTRO BEDMAR ENCINAS 282 I.E.S. "LUIS CARRILLO DE BAENA POETA 173 CEIP "SANTA MARÍA" BAENA. Albendín ANGEL MAYORAL 258 CEIP"SOR FELIPA DE LA CRUZ" BELALCAZAR CORPUS BARGA 73 I.E.S. "JUAN DE SOTO ALVARADO" BELALCAZAR SOTO ALVARADO 262 CEIP"NTRA.SRA.DE LOS REMEDIOS" BELMEZ DIDACTIA 47 I.E.S. "JOSÉ ALCANTARA" BELMEZ SIERRA DE BELMEZ 222 I.E.S. "JOSÉ ALCANTARA" BELMEZ SIERRA BOYERA 249 CEIP "MENENDEZ Y PELAYO" BENAMEJÍ MENENDEZ Y PELAYO 82 CEIP "VIRGEN DE GRACIA" BENAMEJÍ EL JARDÍN 113 I.E.S. "DON DIEGO DE BERNUY" BENAMEJÍ PELUSA CULTURAL 248 CEIP "INMACULADA DEL VOTO" BUJALANCE BORJALIMAR 46 CEIP "JUAN DIAZ DEL MORAL" BUJALANCE BUAMPA 45 I.E.S. -

La Crónica Del Alto Guadalquivir

La Crónica del NOVEMBRE DEL 2020 Alto EJEMPLAR GRATUITO Nº 225 DIRECTOR: RAFAEL ROMERO CASTILLO DEPÓSITO LEGAL: CO-1335/2001 Guadalquivir LA JUNTA PRESUPUESTA PARA EL7 LA HERMANDAD DEL SANTO 10 IPRODECO DESTINA 12.000 11 2021 EL NUEVO CENTRO DE ENTIERRO DE PEDRO ABAD EUROS A LA DINAMIZACIÓN DEL SALUD DE MONTORO PRESENTA UNA NUEVA TALLA COMERCIO DE VILLAFRANCA CRÓNICA Un positivo entre 684 de cribados masivos La Junta de Andalucía ha realizado test en los municipios de Bujalance, Montoro y Villa del Río para detectar la situación de los contagios La Crónica de Alto Guadalquivir 2 Actualidad NOVIEMBRE DEL 2020 Análidad El Covid-19 en la comarca ; Solo un positivo en los cribados masivos hechos en Bujalance, Montoro y Villa del Río Entre los tres municipios fueron 684 las personas sometidas a los test, demostrando un descenso de la curva de contagios CRÓNICA R. CASTRO J. ESCAMILLA ALTO GUADALQUIVIR/ a comarca del Alto Guadalquivir ha sido pun- tera en la realización de cribados, debido al alto Líndice de contagios de Covid-19 producido en varios munici- pios. Si en octubre fue en El Carpio, en noviembre le ha toca- do a Bujalance, Montoro y Villa del Río. Tras el cribado realizado en Bujalance, no se registró nin- gún positivo de los 227 test rápi- dos de antígenos realizados por el Servicio Andaluz de Salud en el Pabellón Municipal de Deportes Pepe Montalbán, un cribado masivo que se ha reali- zado de forma voluntaria, ya que aunque actualmente Bujalance está bajando conside- rablemente en el número de afectados, llegó a tener una inci- dencia muy alta de coronavirus. -

Campiña De Córdoba Ruta Cultural Del Legado Andalusí Las Terrazas Del Guadalquivir (17 Parcial) + Campiñas Altas (39 Parcial) + Campiñas Bajas (40 Parcial) 06

06 PEDRO ABAD#0 VILLA DEL RIO CARPIO (EL) CÓRDOBA Río Guadalquivir !.#0Torre de la Iglesia de San Francisco CÓRDOBA BUJALANCE CAÑETE DE LAS TORRES CÓRDOBA !.Torre de la Albolafia Río Guadajoz !.Torre Mocha ZONA ARQUEOLÓGICA #0 DE ATEGUA Torre del Cambronero %2 Torre de las Vírgenes !. !.Castillo de Torreparedones Torre de Don Lucas ARRECIFE!. %2 Castillo Alcalat CASTRO DEL RIO CARLOTA (LA) %2 Castillo FERNAN NUÑEZ ESPEJO #0 Castillo de Dos Hermanas %2 ZONA ARQUEOLÓGICA MONTE ALTO MONTEMAYOR DE TORREPAREDONES Torre Morana Zona-2Torre Morana !.Torre Morana Zona-1 GUIJARROSA (LA) !. ALGARBES (LOS) Castillo RAMBLA (LA)!.%2 %2 #0 Torre de Santo Domingo BAENA Castillo %2Castillo Castillo#0 MONTALBAN DE CORDOBA NUEVA-CARTEYA Castillo MONTILLA Torre del Puerto %2SANTAELLA !. #0 !.Torre del Puerto Castillo de Poley AGUILAR%2 Río Genil Río de Cabra !. AGUILAR %2Castillo MONTURQUE MORILES RIBERA BAJA PUENTE-GENIL %2Castillo Anzur !.Torre de las Quebradas ERMITAS CASTILLOS TORRES - REFERENTES VISUALES N RED FERROVIARIA ESCALA 1:400.000 RÍOS La campiña cordobesa es un amplio ámbito que se extiende al sur de la vega del EJES PRINCIPALES Guadalquivir y que llega hasta las estribaciones de las sierras subbéticas. Se integra sobre todo en el área paisajística de las Campiñas alomadas, acolinadas y sobre cerros, aunque también posee una parte (la noroccidental) en la de Valles, vegas y EJES SECUNDARIOS marismas interiores. Comparte las formas de otras zonas campiñesas andaluzas: formas suaves, acolinadas, muy antropizadas a partir de una abundante red de DEMARCACIÓN cortijos y de la presencia de ciudades de tamaño medio, patrimonialmente muy potentes y que a menudo se encaraman en zonas elevadas y coronadas por castillos VILLAS, ALQUERÍAS Y HACIENDAS y otros elementos defensivos. -

Trinity College Dublin the University of Dublin

Trinity College Dublin The University of Dublin Pump-as-turbines for hydropower energy recovery from on-demand irrigation networks: Flow fluctuation characterisation, energy potential extrapolation, and real-scale implementation. Miguel Crespo Chacón Thesis submitted for the fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Engineering to the University of Dublin, Trinity College. August 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Aonghus McNabola Co-Supervisors: Prof. Juan Antonio Rodríguez Díaz & Prof. Jorge García Morillo Department of Civil, Structural & Environmental Engineering, University of Dublin, Trinity College, Dublin i Declaration I declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at this or any other university and it is entirely my own work. I agree to deposit this thesis in the University’s open access institutional repository or allow the library to do so on my behalf, subject to Irish Copyright Legislation and Trinity College Library conditions of use and acknowledgement. Miguel Crespo Chacón August 2020 Summary More water efficient irrigation techniques have been studied and developed during the last decades, and are becoming of significant importance in arid and semi-arid regions, as these are leading to more energy intensive irrigation infrastructures. This thesis presents hydropower energy recovery as a potential measure to improve the energy efficiency in on-demand irrigation networks. Findings in four main elements of work are developed, presented and discussed, related to: i) flow fluctuations prediction, ii) feasibility assessment, iii) energy potential extrapolation and iv) real-scale implementation. On the first element, a new methodology to predict the in-pipe flow variations in on-demand networks along an irrigation season was developed. -

180321 PO Transparencia

ACTA DE LA SESION ORDINARIA DEL PLENO DE LA EXCMA. DIPUTACION PROVINCIAL DE CORDOBA, CELEBRADO, EN PRIMERA CONVOCATORIA, EL DIA 21 DE MARZO DE 2018 En la ciudad de Córdoba siendo las once horas y diez minutos del día veintiuno de marzo de dos mil dieciocho, se constituye en el Salón de Plenos de esta Excma. Diputación Provincial el Pleno al objeto de celebrar, en primera convocatoria, sesión ordinaria previamente convocada al efecto y correspondiente a este día, bajo la Presidencia del Ilmo. Sr. D. Antonio Ruiz Cruz y con asistencia de los/as siguientes Sres./as Diputados/as: Dª Felisa Cañete Marzo, D. Salvador Blanco Rubio, Dª Ana Mª Carrillo Núñez, D. Antonio Rojas Hidalgo, Dª Aurora Mª Barbero Jiménez, Dª Mª Auxiliadora Pozuelo Torrico, D. Francisco J. Martín Romero, Dª Dolores Amo Camino, D. Carmen Mª Gómez Navajas, D. Maximiano Izquierdo Jurado, D. Martin Torralbo Luque, D. Luis Martín Luna, D. Andrés Lorite Lorite, D. Agustín Palomares Cañete, Dª Carmen Mª Arcos Serrano, Dª Mª Jesús Botella Serrano, Dª Elena Alba Castro, Dª. Cristina Jiménez Lopera, D. Bartolomé Madrid Olmo, D. José Mª Estepa Ponferrada, D. Juan Ramón Valdivia Rosa, D. Francisco A. Sánchez Gaitán, Dª Marisa Ruz García, Dª Ana Mª Guijarro Carmona, Dª Mª de los Ángeles Aguilera Otero y D. José Luis Vilches Quesada. Concurre asimismo D. Alfonso A. Montes Velasco, Interventor General de Fondos de la Corporación, y la sesión se celebra bajo la fé de D. Jesús Cobos Climent, Secretario General de la Corporación Provincial. Abierta la sesión por la Presidencia por concurrir un número de Diputados/as que excede del exigido por la normativa de aplicación y antes de pasar a tratar de los asuntos incluidos en el orden del día, por el Ilmo. -

Actes Dont La Publication Est Une Condition De Leur Applicabilité)

30 . 9 . 88 Journal officiel des Communautés européennes N0 L 270/ 1 I (Actes dont la publication est une condition de leur applicabilité) RÈGLEMENT (CEE) N° 2984/88 DE LA COMMISSION du 21 septembre 1988 fixant les rendements en olives et en huile pour la campagne 1987/1988 en Italie, en Espagne et au Portugal LA COMMISSION DES COMMUNAUTÉS EUROPÉENNES, considérant que, compte tenu des donnees reçues, il y a lieu de fixer les rendements en Italie, en Espagne et au vu le traité instituant la Communauté économique euro Portugal comme indiqué en annexe I ; péenne, considérant que les mesures prévues au présent règlement sont conformes à l'avis du comité de gestion des matières vu le règlement n0 136/66/CEE du Conseil, du 22 grasses, septembre 1966, portant établissement d'une organisation commune des marchés dans le secteur des matières grasses ('), modifié en dernier lieu par le règlement (CEE) A ARRÊTÉ LE PRESENT REGLEMENT : n0 2210/88 (2), vu le règlement (CEE) n0 2261 /84 du Conseil , du 17 Article premier juillet 1984, arrêtant les règles générales relatives à l'octroi de l'aide à la production d'huile d'olive , et aux organisa 1 . En Italie, en Espagne et au Portugal, pour la tions de producteurs (3), modifié en dernier lieu par le campagne 1987/ 1988 , les rendements en olives et en règlement (CEE) n° 892/88 (4), et notamment son article huile ainsi que les zones de production y afférentes sont 19 , fixés à l'annexe I. 2 . La délimitation des zones de production fait l'objet considérant que, aux fins de l'octroi de l'aide à la produc de l'annexe II . -

Acceso a Escudos Y Banderas Córdoba (Pdf)

Símbolos de las Entidades Locales de Andalucía Córdoba Símbolos de las Entidades Locales de Andalucía Córdoba 147 Córdoba 147~199 148 AGUILAR DE LA FRONTERA 190 TORRECAMPO 149 ALMODÓVAR DEL RIO 191 VALENZUELA 150 BELALCÁZAR 192 VALSEQUILLO 151 BENAMEJÍ 193 VILLA DEL RÍO 152 BUJALANCE 194 VILLAFRANCA DE CÓRDOBA 153 CAÑETE DE LAS TORRES 195 VILLAHARTA 154 CARCABUEY 196 VILLANUEVA DEL REY 155 CARDEÑA 197 VILLAVICIOSA DE CÓRDOBA 156 CONQUISTA 198 ZUHEROS 157 CÓRDOBA (PROVINCIA) 158 EATIM ALDEA DE FUENTE CARRETEROS 159 EATIM ENCINAREJO DE CÓRDOBA 160 EL CARPIO 161 EL GUIJO 162 ENCINAS REALES 163 FERNÁN-NUÑEZ 164 FUENTE LA LANCHA 165 FUENTE PALMERA 166 IZNÁJAR 167 LA CARLOTA 168 LA GRANJUELA 169 LA RAMBLA 170 LA VICTORIA 171 LOS BLÁZQUEZ 172 LUCENA 174 LUQUE 175 MONTEMAYOR 176 MONTILLA 177 MONTORO 179 MORILES 180 OBEJO 181 PALENCIANA 182 PEDRO ABAD 183 PEDROCHE 184 PEÑARROYA-PUEBLONUEVO 185 POSADAS 186 PUENTE GENIL 187 RUTE 188 SAN SEBASTIÁN DE LOS BALLESTEROS 189 SANTA EUFEMIA Consejería de Gobernación. Junta de Andalucía 148 Córdoba Símbolos de las Entidades Locales de Andalucía AGUILAR DE LA FRONTERA Fecha acuerdo autorizando utilizar símbolos: 31/01/07 ESCUDO Descripción: Un águila de sable, emblema parlante de Aguilar, cargada en el pecho de un escudo de oro con tres fajas de gules timbrado con corona ducal sobre el jefe y con el toisón de oro con un collar cuyos eslabones dobles están entrelazados por piedras del rayo, de azur, en llamas de gules. El águila está sur- montada de corona real cerrada. Significado de las figuras del escudo: El águila y el toisón de oro son representativas de la Casa de Aguilar. -

Acta De La Sesion Ordinaria Del Pleno De La Excma

ACTA DE LA SESION ORDINARIA DEL PLENO DE LA EXCMA. DIPUTACION PROVINCIAL DE CORDOBA, CELEBRADO, EN PRIMERA CONVOCATORIA, EL DIA 18 DE MAYO DE 2016 En la ciudad de Córdoba siendo las once horas y veinte minutos del día dieciocho de mayo de dos mil dieciséis, se constituye en el Salón de Plenos de esta Excma. Diputación Provincial el Pleno al objeto de celebrar, en primera convocatoria, sesión ordinaria previamente convocada al efecto y correspondiente a este día, bajo la Presidencia del Ilmo. Sr. D. Antonio Ruiz Cruz y con asistencia de los/as siguientes Sres./as Diputados/as: Dª Ana Mª Carrillo Núñez, D. Antonio Rojas Hidalgo, Dª Aurora Mª Barbero Jiménez, Dª Mª Auxiliadora Pozuelo Torrico, Dª Felisa Cañete Marzo, D. Salvador Blanco Rubio, que abandona la sesión cuando se trataba el punto nº 23 del orden del día, reincorporándose nuevamente cuando se trataba el punto nº 24 del citado orden del día, abandonando nuevamente la sesión cuando se trataba el punto nº 26 del orden del día, reincorporándose nuevamente cuando se trataba el punto nº 27 de repetido orden del día; D. Maximiano Izquierdo Jurado, D. Martín Torralbo Luque, D. Francisco J. Martín Romero, D. Carmen Mª Gómez Navajas, Dª Dolores Amo Camino, D. Andrés Lorite Lorite, D. Fernando Priego Chacón, que se incorpora a la sesión cuando se trataba el punto nº 3 del orden del día; D. Luis Martín Luna, Dª Mª Jesús Botella Serrano, que abandona la sesión cuando se trataba el punto nº 21 del orden del día, reincorporándose nuevamente cuando se trataba el punto nº 25 de dicho orden del día; D. -

Boletin Oficial

JIFliTACIÓi^ Pl^í^V111Giai, AF^CHIVO 161 CÓRDOBA BOLETIN OF IC IAL DE LA PROVINCIA DE CORD OBA Núm. 37 ^ Viernes, 14 de febrero de 1969 I l I EPÓSITO LEGAL, CO. 1.-195ó ^, L.OÑ Ĵ ĈERTADO ^^^ C ^ _ I I _.__ __ TARIFA DE SUSCRIPCION ADVERTENCIA.-Los Alcaldes y Secretaríos dispondrt^n w fije un ejemplar del B. O. en el sítío públíco de costumbr^ AAo Semestre Trimeetré y permanecerá hasta que reciban el siguiente.-Toda claas En la Capital ............................. 550'00 375'00 200'00 de anuncios se envlarán directamente al Excmo. Sr. (30- bernador Civil para que autorice su ínsercíón. En la Provincia y otros puntos . 600'00 450'00 250'00 F:DICTOS DE PAGO: Línea o parte de ella, NUEVE ptas. Edita: La E%CELENTISIMA DIPUTACION PROVINCIAL. Administra.ción y Talleres llmprenta Provincial): Plasa NO SE PUBLICA DOMINGOS NI DL!^S FESTIVOS de Colón, 14. - Teléfonos 22 35 66 9 22 `b8 59 • Venta de ejemplares: Del año actual, 3 pts.; de dos afios anteriores, 5 ptas., y anteriores a los años indicados, 10 ptas. --- -- -- -- --- S U M A R I O PAGB^IA PÁGINA ANUNCIOS DE SIIBAb'TA CiOBIERNO CIVII, Organización Sindical. Obra Sindical del Hogar Concediendo autorización para colocar cebos vene- y de Arqultectura. - Convocando a sut^esta la adjudica- nosos en las fincas que se mencionan de los términos cion de las obras de construcción de viviendas y localrs municipales de Hornachuelos, Espicl y Vlllanueva del comercieles en Córdoba . -..,.. ...... ..... ...... 162 Rey . ............ .... .. ......... ..... 161 ADNIINISTRACION DE JIISTICIA DIPU'I'ACION PROVINCIAL Juzga dos.-Priego de, Córdoba . -

Historia De Las Fuente Sy Pozos De Bujalance. J.M. Abril

Los Pozos y Fuentes de Uso Público de Bujalance y Morente: Patrimonio Cultural, Histórico y Natural LOS POZOS Y FUENTES DE USO PÚBLICO DE BUJALANCE Y MORENTE: PATRIMONIO HISTÓRICO, CULTURAL Y NATURAL Manuel Cala Rodríguez Antonio Luis Luque Lavirgen Rafael Félix Torres José María Abril Hernández Enero de 2011. Los Pozos y Fuentes de Uso Público de Bujalance y Morente: Patrimonio Cultural, Histórico y Natural A quienes han mantenido y a quienes mantengan estos tesoros públicos mojados. M. CALA A los que vivieron de ellos, a los que hoy los maltratamos??, y a los que los necesitarán mañana A.L. LUQUE In memoriam A mi padre, hortelano del alma. Se fue con menguante de invierno. … Y yo solo acierto a regar la tierra con la humedad salobre de la añoranza… A la memoria de mi abuelo, a quien no conocí. José Hernández Peinado murió de hambre amarga en 1940. Yace sin epitafio en el carnero del pueblo de sus amores. De ti heredé una lección, una tarea, y tus ojos tristes… JOSE M. ABRIL 2 Los Pozos y Fuentes de Uso Público de Bujalance y Morente: Patrimonio Cultural, Histórico y Natural PRÓLOGO Por FRANCISCO MARTÍNEZ MEJÍAS, CRONISTA OFICIAL DE BUJALANCE Hace unos meses, los autores me pidieron que actuara como prologuista de esta extraordinaria obra Los Pozos y Fuentes de Uso Público de Bujalance y Morente: Patrimonio Cultural, Histórico y Natural. El recibir esta invitación me llenó de satisfacción, alegría y respeto: cuando a la condición de cronista va aparejada mi amistad y aprecio hacia los autores, y tomando en consideración el extraordinario valor que para mí tiene este tipo de trabajos de investigación sobre temas locales, a los que yo precisamente y desde hace años vengo dedicando todo el tiempo libre que me permite mi actividad profesional, el escribir unas líneas de presentación para su obra no es un trabajo, sino un placer.