Corpus of Mycenaean Inscriptions from Knossos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

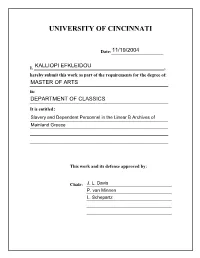

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classical Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2004 by Kalliopi Efkleidou B.A., Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2001 Committee Chair: Jack L. Davis ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE by Kalliopi Efkleidou This work focuses on the relations of dominance as they are demonstrated in the Linear B archives of Mainland Greece (Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae, and Thebes) and discusses whether the social status of the “slave” can be ascribed to any social group or individual. The analysis of the Linear B tablets demonstrates that, among the lower-status people, a social group that has been generally treated by scholars as internally undifferentiated, there were differentiations in social status and levels of dependence. A set of conditions that have been recognized as being of central importance to the description of the -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 8913622 A physically-based simulation approach to three-dimensional computer animation Caldwell, Craig Bemreuter, Ph.D. -

Maritime Matters in the Linear B Tab Lets

MARITIME MATTERS IN THE LINEAR B TAB LETS "Unfortunately, we know nothing about the nature and type of organization of the Aegean seaborne trade" I_ Even in the two years that this statement has been in print, it has become hyperbolic, if not untrue, especially in regard to trade with Minoan Crete 2. It is my aim in this paper to A. ALTMAN, "Trade Between the Aegean and the Levant in the Late Bronze Age: Some Neglected Questions", in M. HEL TZER and E. LIPINSKI eds., Society and Economy in the Eastern Mediterranean (Leuven 1988), 231. I use the following abbreviated references: AR : Archaeological Reports; Col/Myc: E. RISCH and H. MO&ESTEIN eds., Colloquium Mycenaeum (Geneva 1979); DicEt: P. Chantraine, Dictionnaire erymologique de la langue grecque (Paris 1968-1980); DMic: F. AURA JORRO, Diccionario Micenico (Madrid 1985); Docs2: M. VENTRIS and J. CHADWICK, Documents in Mycenaean Greek, 2nd ed. (Cambridge 1973); Evidence/or Trade: G.F. BASS, "Evidence for Trade from Bronze Age Shipwrecks", in N.H. Gale and Z.A. Stos-Gale eds., Science and Archaeology: Bronze Age Trade in the Mediterranean (SIM A fonhcoming); lnterp: L.R. PALMER, The Interpretation of Mycenaean Greek Texts (Oxford 1963); LCE: R. TREUIL, P. DARCQUE, J.-C. POURSAT, G. TOUCHAIS, Les civilisa1ions egeennes du Neolithique et de /'Age du Bronze (Paris 1989); MG: R. HOPE SIMPSON, Mycenaean Greece (Park Ridge, NJ 1981); Muster: 1. CHADWICK, "The Muster of the Pylian Fleet", in P.H. ILIEVSKI and L. CREPAJAC eds., Tractata Mycenaea (Skopje 1987), 75-84; MycStud: E.L. BENNETT, Jr. ed., Mycenaean Studies (Madison 1964); Nature of Minoan Trade: M.H. -

SPRING MEETING PLANS for PAAH 7, a Collaborative Issue With

NO. 78 MARCH 1999 information is received, a task that importance." Let me add that Sheila PRESIDENT’S Konrad has volunteered to continue. Hooker, James' widow, is very CORNER Please send changes or additions to him pleased. Our most recent publication, the at [email protected]. New printed On the subject of our publications, second edition of The Directory of copies will be created as needed. we have reason to claim some fair Ancient Historians in the United States, Another recent publication is also financial success: royalties last year should now be in your hands. It available: James Hooker's essays on were $860.00, a chunk of which came represents three years of effort, the The Coming of the Greeks, our second from Jack Cargill's privately-funded assistance of many including the special volume. It is available through Handbook for Ancient History compilers of the original directory, Regina Books at $9.00 for members, Classes. Richard Talbert and Robert Wallace, $13.95 for non-members. Briggs Our list should continue to grow. and the coordination provided by Twyman, among the first to obtain a Gene Borza has delivered his Konrad Kinzl. Our plan is to update copy, wrote "The reproduction of manuscript for PAAH 6 on Macedon the entries on the electronic version as Hooker's articles should prove of great before Alexander. Readers have copies; now we must examine the state of the treasury. Next year may provide the contents SPRING MEETING PLANS for PAAH 7, a collaborative issue with the provisional title Current Concepts The 1999 annual meeting of the Association will be held in New York on May 7-9 at and the Study of Ancient History. -

Thinking Comparatively About Greek Mythology XVII, with Placeholders

Thinking comparatively about Greek mythology XVII, with placeholders that stem from a conversation with Tom Palaima, starting with this question: was He#rakle#s a Dorian? The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2019.11.15. "Thinking comparatively about Greek mythology XVII, with placeholders that stem from a conversation with Tom Palaima, starting with this question: was He#rakle#s a Dorian?." Classical Inquiries. http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/item/52001640-e649-499d- a25b-f75dbf1e38b7/D192_ThinkingComparatively_XVII.pdf? sequence=1&isAllowed=y Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42180969 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. -

The Linear B Syllabary of Bronze Age Greece Ester Salgarella 1 Writing In

Reconstruction of an orthographic system: The Linear B syllabary of Bronze Age Greece Ester Salgarella 1 Writing in Bronze Age Greece: Linear B in context A number of writing systems are witnessed to have been in use in Bronze Age Greece, having had as their cradle the island of Crete, situated in the middle of the Aegean sea at a crossroad between Europe, Egypt and the Levant. From a typological perspective, all these writing systems are syllabaries, meaning that each graphic sign represents a syllable (e.g. /pa/, /ri/, /e/) and is a phonological unit in the script. These syllabaries were also complemented with a set of logographic signs, depicting real-world referents and standing for words or concepts, not individual syllables. Crete first saw the rise of Cretan Hieroglyphic and the Linear A script: the former is understood to be a north/east Cretan phenomenon (with major find-spots at Knossos, Mallia and Petras) in use in the period ca. 1900-1700 BCE; the latter, with its original nucleus probably to be sought in central Crete (Phaistos), shows a much wider geographical distribution (across Crete, on the Aegean islands, some finds also in Asia Minor) as well as time-span, ca. 1800-1450. Both scripts are still undeciphered and are understood to encode the indigenous language(s) of Bronze Age Crete (on Linear A see esp. Schoep, 2002; Davis, 2014; Salgarella, in press; on Cretan Hieroglyphic see esp. Olivier and Godart, 1996; Ferrara, 2015; Decorte, 2017, 2018). The role played by Linear A, and the civilisation responsible for creating and making use of such writing – the so-called ‘Minoans’ in the literature – cannot be over-estimated, so much so that over time Linear A was taken as a template (mother-script) for the creation of another two writing systems: Linear B, used on Crete and Mainland Greece in the period ca. -

Michael Ventris Papers Finding

Michael Ventris Papers Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory (PASP) Classics Department University of Texas at Austin Collection Summary Creator: Michael Ventris Title: Michael Ventris Papers Inclusive Dates: 1948-1956 Bulk Dates: 1948-1956 Abstract: The publications, manuscripts, and correspondence of Michael Ventris, the man credited with the decipherment of Linear B in 1952. Correspondence includes letters with various colleagues and associates, primarily Emmett L. Bennett, Jr. Alice E. Kober, and Sir John L. Myres. Quantity: Five document boxes in the PASP offices; 249 items (6.5 linear feet/1.75 cubic feet) Call Number: N/A, pending Administrative Information Acquisition Information: Donors: Emmett Bennett, Jr., Thomas G. Palaima, the Ashmolean Museum, and the University of Uppsala. Donation Date: 1985 Processing Information: Item level inventory and finding aid. By: C. Costlow Date: Fall 2007 i Index Terms Persons Bennett, Emmett L., Jr. Blegen, Carl Chadwick, John Daniel, John Franklin Hrozný, B. Hunter, Patrick Kober, Alice Myres, Sir John Sittig, Ernst Ventris, Lois Organizations Architectural Association Royal Air Force Publications American Journal of Archaeology Antiquity Archaeology Documents in Mycenaean Greek Études Mycéniennes Jahrbuch für kleinasiatische Forschung The Listener Subjects Cypro-Minoan Decipherment Linear A Linear B Minoan Syllabary Statistical Analysis Places Crete Greece London Oxford Pylos Knossos Scarborough Document Types Articles Carbon copies ii Letters Offprints Photocopies Transcripts ii Creator Sketch Michael George Francis Ventris (1922–1956) was born in Wheathamstead, England, and educated privately in England and Switzerland and later at Stowe School from 1935 to 1939. As a boy, Ventris was fascinated with the classics, and much of his early education was of an informal nature, obtained primarily though books, travel, and self-taught languages. -

Women in Mycenaean Greece: the Linear B Textual Evidence

Braun | 7 Women in Mycenaean Greece: The decipherment, as she concluded that Linear B recorded an inflected language, even without knowing it recorded Greek.3 Carl Blegen was Linear B Textual Evidence an important contributor, making the Linear B tablets he excavated at Pylos available to specialized scholars. In fact, his testing of Ventris’ syllabary on the famous Tripod Tablet (PY Ta 641) definitively proved Graham Braun that Linear B recorded Greek. In addition to the above names, Emmett Bennett and Sterling Dow both played influential roles. So, while The Linear B script, inscribed on clay tablets recording the movement of Ventris was the first to develop a comprehensive and accurate sylla- commodities and people within the palaces of Mycenaean Greece (ca. 1700– bary, the Linear B decipherment would not have been possible with- 1150 BCE), offers Classical scholarship a wealth of information regard- out certain scholars creating the groundwork for Ventris’ discovery. ing the linguistic, economic, religious, and social developments of early The Greek Bronze Age (ca. 3000–1100 BCE) was a period of Greece. Yet the study of women in Mycenaean Greece has only recently dynamic interconnection throughout the Aegean Sea and wider Eastern arisen as an area of interest. While the Linear B texts present issues regard- Mediterranean. While powerful civilizations like Mesopotamia and ing archaeological context and translational difficulties, they nevertheless Egypt dominated their respective domains, prehistoric Greek civiliza- reveal much about three general classes of women: lower-class peasants, tions interacted with them through trade relations, thereby experienc- religious officials, and aristocratic women. This paper analyzes how these ing a lot of cultural exchange. -

Alice Kober, Her Phonetic Chart, and the Decipherment of Linear B

Charting the Unknown: Alice Kober, Her Phonetic Chart, and the Decipherment of Linear B Brenna Wheeler University of Texas at Austin Ancient History and History Class of 2017 Abstract: This paper analyzes a phonetic chart of Linear B symbols found in the notebook of Dr. Alice E. Kober to determine how accurately she identified phonetic relationships between the signs and how this chart influenced Michael Ventris’s later decipherment. Of the 87 signs in Linear B, only twenty signs were plotted on Kober’s chart, only ten of which were published in her 1948 article, “The Minoan Scripts: Fact and Theory”. The remaining ten signs were written tentatively in pencil and remained unpublished. The only notes about how Kober created these charts were three assumptions she published in the article above, but no explanation was given about the remaining ten signs on her chart. By looking at the current, accepted phonetic values of each sign, I will identify possible reasons behind the placement of certain signs relative to others and the accuracy of Kober’s analysis. Then, I will examine some of Ventris’s phonetic charts and writings to understand how Kober’s work impacted his decipherment of Linear B. Ultimately, I will argue that although Kober’s published chart was fairly accurate in the few signs she plotted, Ventris decided to identify the phonetic values himself. In doing so he would adopt Kober’s grid layout, her use of alternate spellings, and her theory of how language inflection showed itself in syllabary scripts to create his own phonetic charts until his final decipherment of Linear B in 1952. -

John Chadwick

JOHN CHADWICK Copyright © The British Academy 2002 – all rights reserved John Chadwick 1920–1998 IN THE 1970s A DISTINGUISHED British scholar was visiting one of the main museums in the United States. He could not find the object that he wanted to see, and giving his name as Professor Chadwick from England at the enquiry desk, he asked if he could be shown it. He was gratified, if a little surprised, at once to be given the red carpet treatment, in the form of a conducted tour of the entire museum by the Director himself. It was only when he was taking his leave, and the Director made a remark about the decipherment of Linear A, that he realised that an embarrassing mis- take had been made. It was not him, the Revd Professor Henry Chadwick, FBA, at that time Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, that the museum thought they were welcoming, but a namesake (though not a relative) whom he knew and greatly admired: John Chadwick, also a Fellow of the Academy, and Perceval Maitland Laurence Reader in Classics at Cambridge University. Even in the 1970s, John Chadwick’s celebrity, not least abroad, was not a recent development. It had its origins in the 1950s and his associa- tion, when still in his early thirties, with one of the great intellectual achievements of the century: the decipherment by an even younger con- temporary, Michael Ventris, of the Linear B script used in the late Second Millennium BC in Crete and the Greek mainland. It was a fame that did not fade: when Chadwick died on 24 November 1998, aged 78, obituaries appeared, not only in all the English broadsheets, but also in publications not normally given to noting the passing of Cambridge Classical philologists, among them the New York Times and Der Spiegel. -

The Decipherment: People, Process, Challenges Anna P

Codebreakers and Groundbreakers Extract from a letter from Michael Ventris to Stuart Piggott in Oxford, 21 September 1953. Courtesy of the Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford. Codebreakers and Groundbreakers First published in 2017 by The Fitzwilliam Museum Trumpington Street Cambridge, cb1 2rb www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk Designed and typeset by Palindrome Printed in England by Charlesworth Press © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The right of the authors of the articles to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-1-910731-09-3 Codebreakers and Groundbreakers edited by Yannis Galanakis, Anastasia Christophilopoulou and James Grime Contents Acknowledgements vii Foreword Tim Knox (Director, The Fitzwilliam Museum) ix Preface Anastasia Christophilopoulou (Cyprus Curator-Assistant Keeper, Department of Antiquities, The Fitzwilliam Museum) xi Part 1 The Decipherment of Linear B 1 Discovering Writing in Bronze Age Greece Yannis Galanakis (Senior Lecturer in Classics and Director of the Museum of Classical Archaeology, Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge) 1 2 The Decipherment: People, Process, Challenges Anna P. Judson (Junior Research Fellow in Classics, Gonville and Caius College, Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge) 15 3 Reading Between the Lines: The Worlds of Linear B John Bennet (Director of the British School at Athens and Professor of Aegean Archaeology, University of Sheffield) 30 4 The Other Pre-alphabetic Scripts of Crete and Cyprus Philippa M. -

Late Minoan II Knossos in Mycenaean History

CRETA CAPTA Late Minoan II Knossos in Mycenaean History THEODORE M. S. NASH A THESIS PRESENTED TO VICTORIA UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN CLASSICAL STUDIES 2017 Frontispiece: Throne Room at Knossos with restored griffin frescoes. Author’s photo. 1 Creta Capta Late Minoan II Knossos in Mycenaean History Theodore Matthew Spencer Nash Supervised by Dr. Judy K. Deuling. 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 7 Note ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Chronological Table ......................................................................................................... 9 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter I: The Mycenaean Revolution......................................................................... 16 I.1: Chronology ............................................................................................................. 17 I.2: Origins of the Mycenaean Palatial Age ................................................................ 23 I.2.1: The Architectural Evidence ............................................................................