Homeric -Φι(Ν) Is an Oblique Case Marker*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does English Have a Genitive Case? [email protected]

2. Amy Rose Deal – University of Massachusetts, Amherst Does English have a genitive case? [email protected] In written English, possessive pronouns appear without ’s in the same environments where non-pronominal DPs require ’s. (1) a. your/*you’s/*your’s book b. Moore’s/*Moore book What explains this complementarity? Various analyses suggest themselves. A. Possessive pronouns are contractions of a pronoun and ’s. (Hudson 2003: 603) B. Possessive pronouns are inflected genitives (Huddleston and Pullum 2002); a morphological deletion rule removes clitic ’s after a genitive pronoun. Analysis A consists of a single rule of a familiar type: Morphological Merger (Halle and Marantz 1993), familiar from forms like wanna and won’t. (His and its contract especially nicely.) No special lexical/vocabulary items need be postulated. Analysis B, on the other hand, requires a set of vocabulary items to spell out genitive case, as well as a rule to delete the ’s clitic following such forms, assuming ’s is a DP-level head distinct from the inflecting noun. These two accounts make divergent predictions for dialects with complex pronominals such as you all or you guys (and us/them all, depending on the speaker). Since Merger operates under adjacency, Analysis A predicts that intervention by all or guys should bleed the formation of your: only you all’s and you guys’ are predicted. There do seem to be dialects with this property, as witnessed by the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, entry for you-all). Call these English 1. Here, we may claim that pronouns inflect for only two cases, and Merger operations account for the rest. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Genitive Case

GENITIVE CASE The Genitive is the third and last case existing in both English and Latin. In English, all pronouns have a genitive case that shows possession: "his", "her", "my", "their", "whose", etc. These answer the question "Belonging to whom or what?" Regular nouns in English also have a genitive form: in the singular, the ending "'s" is added; in the plural, s'. Consider the following examples: Their father is here. The man's father is here. The boys' father is here. In Latin, the Genitive case may also show possession. However, it may be used for some other things as well, as you will see later on. It's ending of course varies depending on the original ending of the noun: for a-nouns, the singular is -ae and the plural is -ārum; for both us- and um-nouns, the singular is -ī and the plural is - ōrum. Consider the following chart: Nominative, Accusative, and Genitive Cases a-nouns us-nouns um-nouns sg. pl. sg. pl. sg. pl. Nominative a ae us ī um a Accusative Genitive ae ārum ī ōrum ī ōrum A genitive is normally paired with another noun in the sentence which it modifies. In English, it is always placed immediately before the noun it modifies: for example, "my soup", "the boy's shirt", etc. But in Latin, a genitive may be placed either before or after the noun it modifies: for example, feminae panes, panes feminae. In fact, a genitive may occasionally even be separated by another word: panes sunt feminae. Also, keep in mind that the grammatical possession that the genitive case signifies is a fairly broad and vague connection. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Russian Case Morphology and the Syntactic Categories David Pesetsky (MIT)1 • Terminology: I Will Use the Abbreviations NGEN, DNOM, VACC, PDAT, Etc

Russian case morphology and the syntactic categories David Pesetsky (MIT)1 • Terminology: I will use the abbreviations NGEN, DNOM, VACC, PDAT, etc. to remind us of the traditional names for the cases whose actual nature is simply N, D, V, and 1. Introduction (types of) P. The case-name suffixes to these designations are thus present merely for our convenience. • Case morphology: Russian nouns, adjectives, numerals and demonstratives bear case Genitive: The most unusual aspect of the proposal will be the treatment of genitive as suffixes. The shape of a given case suffix is determined by two factors: N -- with which I will begin the discussion in the next section. 1. its morphological environment (properties of the stem to which the suffix attaches; e.g. declension class, gender, animacy, number) ; and • Syntax: The treatment of case as in (1) will depend on two ideas that are novel in the context of a syntax based on external and internal Merge, but are also revivals of well- 2. its syntactic environment. known older proposals, as well as a third important concept: The traditional cross-classification of case suffixes by declension-class and by case- name (nominative, genitive, etc.) reflects these two factors. 1. Morphology assignment: When [or a projection of ] merges with and assigns an affix, the affix is copied α α β α • Specialness of the standard case names: Traditionally, the cases are called by onto β and realized on the (accessible) lexical items dominated by β. special names (nominative, genitive, etc.) not used outside the description of case- systems. The specialness of case terminology reflects what looks like a complex This proposal revives the notion of case assignment (Vergnaud (2006); Rouveret & relation between syntactic environment and choice of case suffix. -

Case in Standard Arabic: a Dependent Case Approach

CASE IN STANDARD ARABIC: A DEPENDENT CASE APPROACH AMER AHMED A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN LINGUISTICS AND APPLIED LINGUISTICS YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO August 2016 © AMER AHMED, 2016 ABSTRACT This dissertation is concerned with how structural and non-structural cases are assigned in the variety of Arabic known in the literature as Standard Arabic (SA). Taking a Minimalist perspective, this dissertation shows that the available generative accounts of case in SA are problematic either theoretically or empirically. It is argued that these problems can be overcome using the hybrid dependent case theory of Baker (2015). This theory makes a distinction between two types of phases. The first is the hard phase, which disallows the materials inside from being accessed by higher phases. The second is the soft phase, which allows the materials inside it to be accessed by higher phases. The results of this dissertation indicate that in SA (a) the CP is a hard phase in that noun phrases inside this phase are inaccessible to higher phases for the purpose of case assignment. In contrast, vP is argued to be a soft phase in that the noun phrases inside this phase are still accessible to higher phases for the purposes of case assignment (b) the DP, and the PP are also argued to be hard phases in SA, (c) case assignment in SA follows a hierarchy such that lexical case applies before the dependent case, the dependent case applies before the Agree-based case assignment, the Agree-based case assignment applies before the unmarked/default case assignment, (d) case assignment in SA is determined by a parameter, which allows the dependent case assignment to apply to a noun phrase if it is c-commanded by another noun phrase in the same Spell-Out domain (TP or VP), (e) the rules of dependent case assignment require that the NPs involved have distinct referential indices. -

Estonian Transitive Verbs and Object Case

ESTONIAN TRANSITIVE VERBS AND OBJECT CASE Anne Tamm University of Florence Proceedings of the LFG06 Conference Universität Konstanz Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2006 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract This article discusses the nature of Estonian aspect and case, proposing an analysis of Estonian verbal aspect, aspectual case, and clausal aspect. The focus is on the interaction of transitive telic verbs ( write, win ) and aspectual case at the level of the functional structure. The main discussion concerns the relationships between aspect and the object case alternation. The data set comprises Estonian transitive verbs with variable and invariant aspect and shows that clausal aspect ultimately depends on the object case. The objects of Estonian transitive verbs in active affirmative indicative clauses are marked with the partitive or the total case; the latter is also known as the accusative and the morphological genitive or nominative. The article presents a unification-based approach in LFG: the aspectual features of verbs and case are unified in the functional structure. The lexical entries for transitive verbs are provided with valued or unvalued aspectual features in the lexicon. If the verb fully determines sentential aspect, then the aspectual feature is valued in the functional specifications of the lexical entry of the verb; this is realized in the form of defining equations. If the aspect of the verb is variable, the entry’s functional specifications have the form of existential constraints. As sentential aspect is fully determined by the total case, the functional specifications of the lexical entry of the total case are in the form of defining equations. -

Download This PDF File

2019. Proceedings of the Workshop on Turkic and Languages in Contact with Turkic 4. 132–146. https://doi.org/10.3765/ptu.v4i1.4587 Delineating Turkic non-finite verb forms by syntactic function Jonathan North Washington & Francis M. Tyers ∗ Abstract. In this paper, we argue against the primary categories of non-finite verb used in the Turkology literature: “participle” (причастие ‹pričastije›) and “converb” (деепричастие ‹de- jepričastije›). We argue that both of these terms conflate several discrete phenomena, and that they furthermore are not coherent as umbrella terms for these phenomena. Based on detailed study of the non-finite verb morphology and syntax of a wide range of Turkic languages (pre- sented here are Turkish, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Tuvan, and Sakha), we instead propose de- lineation of these categories according to their morphological and syntactic properties. Specif- ically, we propose that more accurate categories are verbal noun, verbal adjective, verbal ad- verb, and infinitive. This approach has far-reaching implications to the study of syntactic phe- nomena in Turkic languages, including phenomena ranging from relative clauses to clause chain- ing. Keywords. non-finite verb forms; Turkic languages; converbs; participles 1. Introduction. In the Turkology literature, non-finite verb forms are categorised as either “participles” or “converbs” (corresponding respectively to причастие ‹pričastije› and деепричастие ‹dejepričastije› in the Turkology literature in Russian). These terms are intended to explain the ways in which these mor- phemes (which are almost entirely suffixes) may be used. Sources from throughout the Turkology liter- ature that group all non-finite forms in a given Turkic language into these two categories include Şaʙdan uulu & Batmanov (1933) for Kyrgyz, Дыренкова (1941) for Shor, Убрятова et al. -

Montague Grammatical Analysis of Japanese Case Particles

Montague Grammatical Analysis of Japanese Case Particles Mitsuhiro Okada and Kazue Watanabe Keio University Sophia University 1 Introduction The Montague Grammar for English and other Indo-European languages in the literature is based on the subject-predicate relation, which has been the tradition since Aristotle in the Western language analysis. In this sense, for example, an object and a transitive verb are part of a verb phrase, that is, of a predicate, and the types of a transitive verb and of an object are assigned after the type of predicate (verb phrase) is fixed. When we try to construct categorial grammar and denotational semantics following this tradition, we meet the following deficiencies; • The type structure for transitive verbs and objects, hence their denota- tions, becomes very complicated. For example, the type for transitive verbs is; ((e t) —+ t) (e -4 t) • In order to get an appropriate type for a sentence within the ordinary categorial grammar, we first concatenate a transitive verb with an object and then a subject with the result of the first concatenation. Hence, the resulting grammar becomes very much word-order sensitive. It is easily seen that this kind of operation is not suitable for languages which have word-order flexibility like Japanese, where the following sentences are equivalent in meaning "I ate a cake."; (1) a. Watashi ga cake wo tabeta. I NOM cake ACC ate b. Cake wo watashi ga tabeta. cake ACC I NOM ate We employ the following notational convention in this paper. To each ex- ample sentence of Japanese, we append a gloss which shows the corresponding English expression to each Japanese word and an English translation. -

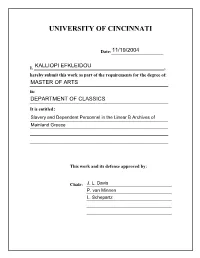

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classical Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2004 by Kalliopi Efkleidou B.A., Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2001 Committee Chair: Jack L. Davis ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE by Kalliopi Efkleidou This work focuses on the relations of dominance as they are demonstrated in the Linear B archives of Mainland Greece (Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae, and Thebes) and discusses whether the social status of the “slave” can be ascribed to any social group or individual. The analysis of the Linear B tablets demonstrates that, among the lower-status people, a social group that has been generally treated by scholars as internally undifferentiated, there were differentiations in social status and levels of dependence. A set of conditions that have been recognized as being of central importance to the description of the