P O T N I a the Divine Names Encountered on the Mycenaean Tablets Open up a Whole New Field for Investigation. the Final Conclus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Athenians and Eleusinians in the West Pediment of the Parthenon

ATHENIANS AND ELEUSINIANS IN THE WEST PEDIMENT OF THE PARTHENON (PLATE 95) T HE IDENTIFICATION of the figuresin the west pedimentof the Parthenonhas long been problematic.I The evidencereadily enables us to reconstructthe composition of the pedimentand to identify its central figures.The subsidiaryfigures, however, are rath- er more difficult to interpret. I propose that those on the left side of the pediment may be identifiedas membersof the Athenian royal family, associatedwith the goddessAthena, and those on the right as membersof the Eleusinian royal family, associatedwith the god Posei- don. This alignment reflects the strife of the two gods on a heroic level, by referringto the legendary war between Athens and Eleusis. The recognition of the disjunctionbetween Athenians and Eleusinians and of parallelism and contrastbetween individualsand groups of figures on the pedimentpermits the identificationof each figure. The referenceto Eleusis in the pediment,moreover, indicates the importanceof that city and its majorcult, the Eleu- sinian Mysteries, to the Athenians. The referencereflects the developmentand exploitation of Athenian control of the Mysteries during the Archaic and Classical periods. This new proposalfor the identificationof the subsidiaryfigures of the west pedimentthus has critical I This article has its origins in a paper I wrote in a graduateseminar directedby ProfessorJohn Pollini at The Johns Hopkins University in 1979. I returned to this paper to revise and expand its ideas during 1986/1987, when I held the Jacob Hirsch Fellowship at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. In the summer of 1988, I was given a grant by the Committeeon Research of Tulane University to conduct furtherresearch for the article. -

The Birds and Plato's Symposium.Pdf

Baquerizo 1 Olivia M. Baquerizo ([email protected]) CAMWS 2021, Plato Panel Fordham Univeristy Friday, April 9 Aetiologies of Eros: The Birds and Plato’s Symposium abstract: https://camws.org/sites/default/files/meeting2021/abstracts/2389AetiologiesofEros.pdf Ephialtes and Otus in the Platonic Aristophanes’ Speech 1. Ephialtes and Otus in the Symposium (190b.5-190c) trans. Nehamas and Woodruff ἦν οὖν τὴν ἰσχὺν δεινὰ καὶ τὴν ῥώμην, καὶ τὰ In strength and power, therefore, they were φρονήματα μεγάλα εἶχον, ἐπεχείρησαν δὲ τοῖς θεοῖς, terrible, and they had great ambitions. They καὶ ὃ λέγει Ὅμηρος περὶ Ἐφιάλτου τε καὶ Ὤτου, περὶ made an attempt on the gods, and homer’s ἐκείνων λέγεται, τὸ εἰς τὸν οὐρανὸν ἀνάβασιν story about Ephiatles and Otus was ἐπιχειρεῖν ποιεῖν, ὡς ἐπιθησομένων τοῖς θεοῖς originally about them: how they tried to make an ascent to heaven so as to attack the gods. 2. Ephialtes and Otus in the Odyssey (11.306-20) trans. A. S. kline τὴν δὲ μετ᾽ Ἰφιμέδειαν, Ἀλωῆος παράκοιτιν Next I saw Iphimedeia, Aloeus’ wife, who εἴσιδον, ἣ δὴ φάσκε Ποσειδάωνι μιγῆναι, claimed she had slept with Poseidon. She καί ῥ᾽ ἔτεκεν δύο παῖδε, μινυνθαδίω δ᾽ ἐγενέσθην, too bore twins, short-lived, godlike Otus and Ὦτόν τ᾽ ἀντίθεον τηλεκλειτόν τ᾽ Ἐφιάλτην, famous Ephialtes, the tallest most handsome οὓς δὴ μηκίστους θρέψε ζείδωρος ἄρουρα men by far, bar great Orion, whom the καὶ πολὺ καλλίστους μετά γε κλυτὸν Ὠρίωνα: 310 fertile Earth ever nourished. They were ἐννέωροι γὰρ τοί γε καὶ ἐννεαπήχεες ἦσαν fifteen feet wide, and fifty feet high at nine εὖρος, ἀτὰρ μῆκός γε γενέσθην ἐννεόργυιοι. -

On the Anatolian Origin of Ancient Greek Σίδη

GRAECO-LATINA BRUNENSIA 19, 2014, 2 KRZYSZTOF TOMASZ WITCZAK (UNIVERSITY OF ŁÓDŹ) MAŁGORZATA ZADKA (UNIVERSITY OF WROCŁAW) ON THE ANATOLIAN ORIGIN OF ANCIENT GREEK ΣΊΔΗ The comparison of Greek words for ‘pomegranate, Punica granatum L.’ (Gk. σίδᾱ, σίδη, σίβδᾱ, σίβδη, ξίμβᾱ f.) with Hittite GIŠšaddu(wa)- ‘a kind of fruit-tree’ indi- cates a possible borrowing of the Greek forms from an Anatolian source. Key words: Greek botanical terminology, pomegranate, borrowings, Anatolian languages. In this article we want to continue the analysis initiated in our article An- cient Greek σίδη as a Borrowing from a Pre-Greek Substratum (WITCZAK – ZADKA 2014: 113–126). The Greek word σίδη f. ‘pomegranate’ is attested in many dialectal forms, which differ a lot from each other what cause some difficulties in determining the possible origin of σίδη. The phonetic struc- ture of the word without a doubt is not of Hellenic origin and it is rather a loan word. It also seems to be related to some Anatolian forms, but this similarity corresponds to a lack of the exact attested words for ‘pomegran- ate’ in Anatolian languages. 1. A Semitic hypothesis No Semitic explanation of Gk. σίδη is possible. The Semitic term for ‘pomegranate’, *rimān-, is perfectly attested in Assyrian armânu, Akka- dian lurmu, Hebrew rimmōn, Arabic rummān ‘id.’1, see also Egyptian (NK) 1 A Semitic name appears in the codex Parisinus Graecus 2419 (26, 18): ποϊρουμάν · ἡ ῥοιά ‘pomegranate’ (DELATTE 1930: 84) < Arabic rummān ‘id.’. This Byzantine 132 KRZYSZTOF TOMASZ WITCZAK, MAŁGORZATA ZADKA rrm.t ‘a kind of fruit’, Coptic erman, herman ‘pomegranate’ (supposedly from Afro-Asiatic *riman- ‘fruit’, esp. -

Download Article (PDF)

Miguel Valério University of Barcelona; [email protected] ̔ΌЁΙΓΖΒΘΚ and word-initial lambdacism in Anatolian Greek The lexical pair formed by Mycenaean da-pu(2)-ri-to- and later Greek ΦΜΝВΪΤΧΣΩΫ presents a contrast between Linear B d and alphabetical Φ in a position where one would expect to find a similar sound represented. This orthographic inconsistency has been taken as a synchronic fluctuation between /d/ and /l/, both optimal adaptations of what is assumed to be a non- Greek (Minoan) sound in da-pu(2)-ri-to-. In turn, it has been proposed that this “special” and wholly theoretical sound, which according to some suggestions was a coronal fricative, was behind the Linear A d series. Here it is argued that there is actually no evidence that /d/ and /l/ alternated synchronically in Mycenaean Greek, and that therefore the /l-/ of ΦΜΝВΪΤΧΣΩΫ is more likely the result of a later shift. Starting from this premise, it is hypothesized that ΦΜΝВΪΤΧΣΩΫ derives from a form closer to Mycenaean da-pu(2)-ri-to-, an unattested *ΟΜΝВΪΤΧΣΩΫ, that underwent a shift /d-/ > /l-/ in Southern or Western Anatolia. The pro- posed motivation is the influence of some local Anatolian language that prohibited /d/ word- initially. The same development is considered for ΦηίΧ and ΦϲάΥΩΫ, which Hesychius glossed as Pergaean (Pamphylian) forms of standard Greek ΟηίΧ ‘sweet bay’ and ΟϲάΥΩΫ ‘discus, quoit’, and possibly also for the Cimmerian personal name Dugdammê/̥ВΞΟΜ÷ΤΫ. Of course, this hypothesis has implications for our perception of the Linear A d series and certain open questions that concern the Aegean-Cypriot syllabaries. -

Ritual Surprise and Terror in Ancient Greek Possession-Dromena

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 2 | 1989 Varia Ritual Surprise and Terror in Ancient Greek Possession-Dromena Ioannis Loucas Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/242 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.242 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1989 Number of pages: 97-104 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Ioannis Loucas, « Ritual Surprise and Terror in Ancient Greek Possession-Dromena », Kernos [Online], 2 | 1989, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 21 April 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/kernos/242 ; DOI : 10.4000/kernos.242 Kernos Kernos, 2 (1989), p. 97-104. RITUAL SURPRISE AND TERROR INANCIENT GREEK POSSESSION·DROMENA The daduch of the Eleusinian mysteries Themistokles, descendant of the great Athenian citizen of the 5th century RC'!, is honoured by a decree of 20/19 RC.2 for «he not only exhibits a manner of life worthy of the greatest honour but by the superiority of his service as daduch increases the solemnity and dignity of the cult; thereby the magnificence of the Mysteries is considered by all men to be ofmuch greater excitement (ekplexis) and to have its proper adornment»3. P. Roussel4, followed by K. Clinton5, points out the importance of excitement or surprise (in Greek : ekplexis) in the Mysteries quoting analogous passages from the Eleusinian Oration of Aristides6 and the Platonic Theology ofProclus7, both writers of the Roman times. ln Greek literature one of the earlier cases of terror connected to any cult is that of the terror-stricken priestess ofApollo coming out from the shrine of Delphes in the tragedy Eumenides8 by Aeschylus of Eleusis : Ah ! Horrors, horrors, dire to speak or see, From Loxias' chamber drive me reeling back. -

The Geotectonic Evolution of Olympus Mt and Its

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, vol. XLVII 2013 Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, τομ. XLVII , 2013 th ου Proceedings of the 13 International Congress, Chania, Sept. Πρακτικά 13 Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου, Χανιά, Σεπτ. 2013 2013 THE GEOTECTONIC EVOLUTION OF OLYMPUS MT. AND ITS MYTHOLOGICAL ANALOGUE Mariolakos I.D.1 and Manoutsoglou E.2 1 National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Faculty of Geology and Geoenvironment, Department of Dynamic, Tectonic & Applied Geology, Panepistimioupoli, Zografou, GR 157 84, Athens, Greece, [email protected] 2 Technical University of Crete, Department of Mineral Resources Engineering, Research Unit of Geology, Chania, 73100, Greece, [email protected] Abstract Mt Olympus is the highest mountain of Greece (2918 m.) and one of the most impor- tant and well known locations of the modern world. This is related to its great cul- tural significance, since the ancient Greeks considered this mountain as the habitat of their Gods, ever since Zeus became the dominant figure of the ancient Greek re- ligion and consequently the protagonist of the cultural regime. Before the genera- tion of Zeus, Olympus was inhabited by the generation of Cronus. In this paper we shall refer to a lesser known mythological reference which, in our opinion, presents similarities to the geotectonic evolution of the wider area of Olympus. According to Apollodorus and other great authors, the God Poseidon and Iphimedia had twin sons, the Aloades, namely Otus and Ephialtes, who showed a tendency to gigantism. When they reached the age of nine, they were about 16 m. tall and 4.5 m. wide. -

Transformation of a Goddess by David Sugimoto

Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 263 David T. Sugimoto (ed.) Transformation of a Goddess Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite Academic Press Fribourg Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Publiziert mit freundlicher Unterstützung der PublicationSchweizerischen subsidized Akademie by theder SwissGeistes- Academy und Sozialwissenschaften of Humanities and Social Sciences InternetGesamtkatalog general aufcatalogue: Internet: Academic Press Fribourg: www.paulusedition.ch Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen: www.v-r.de Camera-readyText und Abbildungen text prepared wurden by vomMarcia Autor Bodenmann (University of Zurich). als formatierte PDF-Daten zur Verfügung gestellt. © 2014 by Academic Press Fribourg, Fribourg Switzerland © Vandenhoeck2014 by Academic & Ruprecht Press Fribourg Göttingen Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen ISBN: 978-3-7278-1748-9 (Academic Press Fribourg) ISBN:ISBN: 978-3-525-54388-7978-3-7278-1749-6 (Vandenhoeck(Academic Press & Ruprecht)Fribourg) ISSN:ISBN: 1015-1850978-3-525-54389-4 (Orb. biblicus (Vandenhoeck orient.) & Ruprecht) ISSN: 1015-1850 (Orb. biblicus orient.) Contents David T. Sugimoto Preface .................................................................................................... VII List of Contributors ................................................................................ X -

Animal Sacrifice in the Mycenaean World," Journal of Prehistoric Religion 15 (2001) 32-38

"Animal Sacrifice in the Mycenaean World," Journal of Prehistoric Religion 15 (2001) 32-38. 4 5 7 Fig. 4. Seal impressionfrom Pylos showinga pre-potnia motif. Fig. 5. Lentoid sealfeaturing a pre potnia scene. Fig. 6. Ivory plaquefrom Mycenae with possiblepotnios theme. Fig. 7. Jasper ringfrom Mycenaefeaturing a potnios theron scene. 10 Animal Sacrifice in the Mycenaean World.* Stephie Nikoloudis Introduction Animal sacrifice is attested, directly and 16) and enhances community spirit indirectly, in the textual, iconographical through an associated celebration and and archaeological remains of the feast (Killen 1994: 70). Interestingly, by Mycenaean Bronze Age. The following serving to intensify group identity, synthesis of the current evidence sacrifice may deliberately exclude (archaeological, iconographical, anthro outsiders (Seaford 1994: xii). At the same pological and textual) is presented in the time, it articulates status and role hope that it may help to generate new divisions, thereby reinforcing the internal insights into this topic. Much new social structure of a given community evidence has appeared in the last decade (Seaford 1994: xii). in all four categories of specialized study. A predominantly synchronic approach It is examined, here, in a combinatory is adopted in comparing the information way. The aim is to ascertain, as far as retrievable from the administrative possible, the identity of the sacrificers and records (tablets and sealings), seals and the receivers, the animals sacrificed and seal-rings, frescoes and archaeological the occasion(s) and place(s) at which this remains from the Mycenaean palatial was carried out, the procedure(s) and centres of Thebes, Pylos and Knossos paraphernalia involved, and the under dating from the LH/LM ill period. -

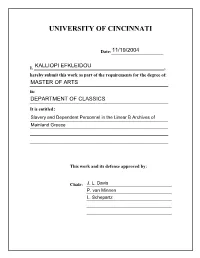

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classical Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2004 by Kalliopi Efkleidou B.A., Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2001 Committee Chair: Jack L. Davis ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE by Kalliopi Efkleidou This work focuses on the relations of dominance as they are demonstrated in the Linear B archives of Mainland Greece (Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae, and Thebes) and discusses whether the social status of the “slave” can be ascribed to any social group or individual. The analysis of the Linear B tablets demonstrates that, among the lower-status people, a social group that has been generally treated by scholars as internally undifferentiated, there were differentiations in social status and levels of dependence. A set of conditions that have been recognized as being of central importance to the description of the -

This Pdf of Your Paper in Aegean Scripts, Proceedings of the 14Th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies Belongs to the P

This pdf of your paper in Aegean Scripts, Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies belongs to the publisher Istituto di Studi sul Mediterraneo Antico (Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche) and it is its copyright. As author you are licensed to make up to 50 offprints from it, but beyond that you may not make it available on the Internet until two years from publication (December 2017). I CNR ISTITUTO DI STUDI SUL MEDITERRANEO ANTICO II INCUNABULA GRAECA VOL. CV, 1 DIRETTORI MARCO BETTELLI · MAURIZIO DEL FREO COMITATO SCIENTIFICO AEGEAN SCRIPTS JOHN BENNET (Sheffield) · ELISABETTA BORGNA (Udine) Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies ANDREA CARDARELLI (Roma) · ANNA LUCIA D’AGATA (Roma) Copenhagen, 2-5 September 2015 PIA DE FIDIO (Napoli) · JAN DRIESSEN (Louvain-la-Neuve) BIRGITTA EDER (Wien) · ARTEMIS KARNAVA (Berlin) Volume I JOHN T. KILLEN (Cambridge) · JOSEPH MARAN (Heidelberg) PIETRO MILITELLO (Catania) · MASSIMO PERNA (Napoli) FRANÇOISE ROUGEMONT (Paris) · JEREMY B. RUTTER (Dartmouth) GERT JAN VAN WIJNGAARDEN (Amsterdam) · CARLOS VARIAS GARCÍA (Barcelona) JÖRG WEILHARTNER (Salzburg) · JULIEN ZURBACH (Paris) PUBBLICAZIONI DELL'ISTITUTO DI STUDI SUL MEDITERRANEO ANTICO DEL CONSIGLIO NAZIONALE DELLE RICERCHE DIRETTORE DELL'ISTITUTO: ALESSANDRO NASO III INCUNABULA GRAECA VOL. CV, 1 DIRETTORI MARCO BETTELLI · MAURIZIO DEL FREO COMITATO SCIENTIFICO AEGEAN SCRIPTS JOHN BENNET (Sheffield) · ELISABETTA BORGNA (Udine) Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies ANDREA CARDARELLI (Roma) · ANNA LUCIA D’AGATA (Roma) Copenhagen, 2-5 September 2015 PIA DE FIDIO (Napoli) · JAN DRIESSEN (Louvain-la-Neuve) BIRGITTA EDER (Wien) · ARTEMIS KARNAVA (Berlin) Volume I JOHN T. KILLEN (Cambridge) · JOSEPH MARAN (Heidelberg) PIETRO MILITELLO (Catania) · MASSIMO PERNA (Napoli) FRANÇOISE ROUGEMONT (Paris) · JEREMY B. -

The Odyssey, Book One 273 the ODYSSEY

05_273-611_Homer 2/Aesop 7/10/00 1:25 PM Page 273 HOMER / The Odyssey, Book One 273 THE ODYSSEY Translated by Robert Fitzgerald The ten-year war waged by the Greeks against Troy, culminating in the overthrow of the city, is now itself ten years in the past. Helen, whose flight to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris had prompted the Greek expedition to seek revenge and reclaim her, is now home in Sparta, living harmoniously once more with her husband Meneláos (Menelaus). His brother Agamémnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, was murdered on his return from the war by his wife and her paramour. Of the Greek chieftains who have survived both the war and the perilous homeward voyage, all have returned except Odysseus, the crafty and astute ruler of Ithaka (Ithaca), an island in the Ionian Sea off western Greece. Since he is presumed dead, suitors from Ithaka and other regions have overrun his house, paying court to his attractive wife Penélopê, endangering the position of his son, Telémakhos (Telemachus), corrupting many of the servants, and literally eating up Odysseus’ estate. Penélopê has stalled for time but is finding it increasingly difficult to deny the suitors’ demands that she marry one of them; Telémakhos, who is just approaching young manhood, is becom- ing actively resentful of the indignities suffered by his household. Many persons and places in the Odyssey are best known to readers by their Latinized names, such as Telemachus. The present translator has used forms (Telémakhos) closer to the Greek spelling and pronunciation. -

For a Falcon

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves CRESCENT BOOKS NEW YORK New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Translated by Richard Aldington and Delano Ames and revised by a panel of editorial advisers from the Larousse Mvthologie Generate edited by Felix Guirand and first published in France by Auge, Gillon, Hollier-Larousse, Moreau et Cie, the Librairie Larousse, Paris This 1987 edition published by Crescent Books, distributed by: Crown Publishers, Inc., 225 Park Avenue South New York, New York 10003 Copyright 1959 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited New edition 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. ISBN 0-517-00404-6 Printed in Yugoslavia Scan begun 20 November 2001 Ended (at this point Goddess knows when) LaRousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves Perseus and Medusa With Athene's assistance, the hero has just slain the Gorgon Medusa with a bronze harpe, or curved sword given him by Hermes and now, seated on the back of Pegasus who has just sprung from her bleeding neck and holding her decapitated head in his right hand, he turns watch her two sisters who are persuing him in fury. Beneath him kneels the headless body of the Gorgon with her arms and golden wings outstretched. From her neck emerges Chrysor, father of the monster Geryon. Perseus later presented the Gorgon's head to Athene who placed it on Her shield.