Saffron Offering and Blood Sacrifice: Transformation Mysteries In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minoan Religion

MINOAN RELIGION Ritual, Image, and Symbol NANNO MARINATOS MINOAN RELIGION STUDIES IN COMPARATIVE RELIGION Frederick M. Denny, Editor The Holy Book in Comparative Perspective Arjuna in the Mahabharata: Edited by Frederick M. Denny and Where Krishna Is, There Is Victory Rodney L. Taylor By Ruth Cecily Katz Dr. Strangegod: Ethics, Wealth, and Salvation: On the Symbolic Meaning of Nuclear Weapons A Study in Buddhist Social Ethics By Ira Chernus Edited by Russell F. Sizemore and Donald K. Swearer Native American Religious Action: A Performance Approach to Religion By Ritual Criticism: Sam Gill Case Studies in Its Practice, Essays on Its Theory By Ronald L. Grimes The Confucian Way of Contemplation: Okada Takehiko and the Tradition of The Dragons of Tiananmen: Quiet-Sitting Beijing as a Sacred City By By Rodney L. Taylor Jeffrey F. Meyer Human Rights and the Conflict of Cultures: The Other Sides of Paradise: Western and Islamic Perspectives Explorations into the Religious Meanings on Religious Liberty of Domestic Space in Islam By David Little, John Kelsay, By Juan Eduardo Campo and Abdulaziz A. Sachedina Sacred Masks: Deceptions and Revelations By Henry Pernet The Munshidin of Egypt: Their World and Their Song The Third Disestablishment: By Earle H. Waugh Regional Difference in Religion and Personal Autonomy 77u' Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: By Phillip E. Hammond Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response Minoan Religion: Ritual, Image, and Symbol By By George D. Bond Nanno Marinatos A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to Their Eclipse Under Islam By Gordon Darnell Newby MINOAN RELIGION Ritual, Image, and Symbol NANNO MARINATOS University of South Carolina Press Copyright © 1993 University of South Carolina Published in Columbia, South Carolina, by the University of South Carolina Press Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Marinatos, Nanno. -

Garcinia Hanburyi Guttiferae Hook.F

Garcinia hanburyi Hook.f. Guttiferae LOCAL NAMES English (gamboge tree); German (Gutti,Gummigutt); Thai (rong); Vietnamese (dang hoang) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION An evergreen, small to medium-sized tree, up to 15 m tall, with short and straight trunk, up to 20 cm in diameter; bark grey, smooth, 4-6 mm thick, exuding a yellow gum-resin. Leaves opposite, leathery, elliptic or ovate-lanceolate, 10-25 cm x 3-10 cm, cuneate at base, acuminate at apex, shortly stalked. Flowers in clusters or solitary in the axils of fallen leaves, 4-merous, pale yellow and fragrant, unisexual or bisexual; male flowers somewhat smaller than female and bisexuals; sepals leathery, orbicular, 4-6 mm long, persistent; petals ovate, 6-7 mm long; stamens numerous and arranged on an elevated receptacle in male flowers, less numerous and reduced in female flowers; ovary superior, 4-loculed, with sessile stigma. Fruit a globose berry, 2-3 cm in diameter, smooth, with recurved sepals at the base and crowned by the persistent stigma, 1-4 seeded. Seeds 15-20 mm long, surrounded by a pulpy aril. The gum-resin from G. hanburyi is often called Siamese gamboge to distinguish it from the similar product from the bark of G. morella Desr., called Indian gamboge. The species are closely related, and G. hanburyi has been considered in the past as a variety of G. morella. BIOLOGY Normally it flowers in November and December and fruits from February to April. Agroforestry Database 4.0 (Orwa et al.2009) Page 1 of 5 Garcinia hanburyi Hook.f. Guttiferae ECOLOGY Gamboge tree occurs naturally in rain forest. -

Historical Uses of Saffron: Identifying Potential New Avenues for Modern Research

id8484906 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ISSN : 0974 - 7508 Volume 7 Issue 4 NNaattuurraall PPrrAoon dIdnduuian ccJotutrnssal Trade Science Inc. Full Paper NPAIJ, 7(4), 2011 [174-180] Historical uses of saffron: Identifying potential new avenues for modern research S.Zeinab Mousavi1, S.Zahra Bathaie2* 1Faculty of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, (IRAN) 2Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, (IRAN) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 20th June, 2011 ; Accepted: 20th July, 2011 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Background: During the ancient times, saffron (Crocus sativus L.) had Saffron; many uses around the world; however, some of them were forgotten Iran; ’s uses came back into attention during throughout the history. But saffron Ancient medicine; the past few decades, when a new interest in natural active compounds Herbal medicine; arose. It is supposed that understanding different uses of saffron in past Traditional medicine. can help us in finding the best uses for today. Objective: Our objective was to review different uses of saffron throughout the history among different nations. Results: Saffron has been known since more than 3000 years ago by many nations. It was valued not only as a culinary condiment, but also as a dye, perfume and as a medicinal herb. Its medicinal uses ranged from eye problems to genitourinary and many other diseases in various cul- tures. It was also used as a tonic agent and antidepressant drug among many nations. Conclusion(s): Saffron has had many different uses such as being used as a food additive along with being a palliative agent for many human diseases. -

Top Things to Do in Santorini" a Volcanic Group of Islands on the Aegean Sea, Santorini Is a Very Famous Tourist Destination

"Top Things To Do in Santorini" A volcanic group of islands on the Aegean Sea, Santorini is a very famous tourist destination. Known for its azure waters, historic relics and fascinating Cycladic architecture, Santorini is a Mediterranean paradise in the truest sense. Criado por : Cityseeker 10 Localizações indicadas Playa de Kamari "Mediterranean Sun and Sand" Blue waters, soft white sands, and the warm Mediterranean sun on your face, Santorini's Playa de Kamari or the Kamari Beach checks all the boxes for an hour or two by the sea. The shore is also lined with eateries where you can grab a bite and drink while soaking in the pristine view. by Stan Zurek Off Makedonias, Santorini Akrotiri "A Lost Minoan World" Akrotiri is a pre-historic settlement that got buried under volcanic ash after the Minoan eruption. Here, the Minoan civilization lives through artifacts as well as everyday items like pottery, oil lamps, and intricately done Frescoes as well as buildings that were all excavated during the early 19th Century and well into the 20th Century. by Rt44 Akrotiri, Santorini Tomato Industrial Museum "A Museum Chronicling Tomato Production" Initially an old D.Nomikos tomato processing factory, the Tomato Industrial Museum is a unique museum that offers a look into the production and processing of tomato, something Santorini is known for. The exhibits such as machines from 1890, first labels, old tools and written accounts provide a glimpse into the old methods followed by the tomato by dafyddbach producers. +30 22860 8 5141 www.santoriniartsfactory. [email protected] Vlychada Beach, Santorini gr/en/museum Arts Factory, Santorini Perissa Beach "Black-Sand Beach" Nestled in the southern region of Santorini, Perissa Beach is one of the beautiful beaches of the island. -

The Study of the E-Class SEPALLATA3-Like MADS-Box Genes in Wild-Type and Mutant flowers of Cultivated Saffron Crocus (Crocus Sativus L.) and Its Putative Progenitors

G Model JPLPH-51259; No. of Pages 10 ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Plant Physiology xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Plant Physiology journal homepage: www.elsevier.de/jplph The study of the E-class SEPALLATA3-like MADS-box genes in wild-type and mutant flowers of cultivated saffron crocus (Crocus sativus L.) and its putative progenitors Athanasios Tsaftaris a,b,∗, Konstantinos Pasentsis a, Antonios Makris a, Nikos Darzentas a, Alexios Polidoros a,1, Apostolos Kalivas a,2, Anagnostis Argiriou a a Institute of Agrobiotechnology, Center for Research and Technology Hellas, 6th Km Charilaou Thermi Road, Thermi GR-570 01, Greece b Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki GR-541 24, Greece article info abstract Article history: To further understand flowering and flower organ formation in the monocot crop saffron crocus (Crocus Received 11 August 2010 sativus L.), we cloned four MIKCc type II MADS-box cDNA sequences of the E-class SEPALLATA3 (SEP3) Received in revised form 22 March 2011 subfamily designated CsatSEP3a/b/c/c as as well as the three respective genomic sequences. Sequence Accepted 26 March 2011 analysis showed that cDNA sequences of CsatSEP3 c and c as are the products of alternative splicing of the CsatSEP3c gene. Bioinformatics analysis with putative orthologous sequences from various plant Keywords: species suggested that all four cDNA sequences encode for SEP3-like proteins with characteristic motifs Crocus sativus L. and amino acids, and highlighted intriguing sequence features. Phylogenetically, the isolated sequences MADS-box genes Monocots were closest to the SEP3-like genes from monocots such as Asparagus virgatus, Oryza sativa, Zea mays, RCA-RACE and the dicot Arabidopsis SEP3 gene. -

ANASTASIOS GEORGOTAS “Archaeological Tourism in Greece

UNIVERSITY OF THE PELOPONNESE ANASTASIOS GEORGOTAS (R.N. 1012201502004) DIPLOMA THESIS: “Archaeological tourism in Greece: an analysis of quantitative data, determining factors and prospects” SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: - Assoc. Prof. Nikos Zacharias - Dr. Aphrodite Kamara EXAMINATION COMMITTEE: - Assoc. Prof. Nikolaos Zacharias - Dr. Aphrodite Kamara - Dr. Nikolaos Platis ΚΑΛΑΜΑΤΑ, MARCH 2017 Abstract . For many decades now, Greece has invested a lot in tourism which can undoubtedly be considered the country’s most valuable asset and “heavy industry”. The country is gifted with a rich and diverse history, represented by a variety of cultural heritage sites which create an ideal setting for this particular type of tourism. Moreover, the variations in Greece’s landscape, cultural tradition and agricultural activity favor the development and promotion of most types of alternative types of tourism, such as agro-tourism, religious, sports and medicinal tourism. However, according to quantitative data from the Hellenic Statistical Authority, despite the large number of visitors recorded in state-run cultural heritage sites every year, the distribution pattern of visitors presents large variations per prefecture. A careful examination of this data shows that tourist flows tend to concentrate in certain prefectures, while others enjoy little to no visitor preference. The main factors behind this phenomenon include the number and importance of cultural heritage sites and the state of local and national infrastructure, which determines the accessibility of sites. An effective analysis of these deficiencies is vital in order to determine solutions in order to encourage the flow of visitors to the more “neglected” areas. The present thesis attempts an in-depth analysis of cultural tourism in Greece and the factors affecting it. -

Cultivation, Distribution, Taxonomy, Chemical Composition and Medical 2003, Pp

The Journal of Phytopharmacology 2017; 6(6): 356-358 Online at:www.phytopharmajournal.com Review Article Cultivation, distribution, taxonomy, chemical composition ISSN 2320-480X and medical importance of Crocus sativus JPHYTO 2016; 6(6): 356-358 November- December Refaz Ahmad Dar*, Mohd. Shahnawaz, Sumera Banoo Malik, Manisha K. Sangale, Avinash B. Ade, Received: 16-10-2017 Accepted: 22-11-2017 Parvaiz Hassan Qazi © 2017, All rights reserved ABSTRACT Refaz Ahmad Dar Division of Microbial Biotechnology, Crocus sativus L. is one of the most important plant belongs to family Iridaceae. It is having various medicinal Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine potential, and is widely being used in food industries. In Jammu and Kashmir State, its cultivation is restricted (CSIR), Sanatnagar, Srinagar, Jammu & to two districts only (Pulwama and Kishtwar). In the present review an attempt was made to highlight the Kashmir-190005, India cultivation practices of saffron, to discuss its distribution around the globe, to specify its taxonomic status, to Mohd Shahnawaz enlist its chemical constituents, and to discuss its various beneficial usages. a) Division of Plant Biotechnology, Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine (CSIR), Jammu - Tawi -180001, India Keywords: Saffron, Cultivation, Iran, Pulwama, Kishtwar, Crocus sativus. b) Department of Botany, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, Maharashtra-411007, India INTRODUCTION Sumera Banoo Malik Division of Cancer Pharmacology, Crocus sativus L. is small perennial plant, considered as king of the spice world. It belongs to Iridaceae. Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine The genus Crocus consists of about 90 species and some are being cultivated for flower. The flowers (CSIR), Jammu & Kashmir-180001, India (three stigmas-distal end of the carpel) of the C. -

Plane Tickets to Santorini Greece

Plane Tickets To Santorini Greece irritatedCourant insanelySaxon emasculate when Clement obsessionally implying his or hushes.nutates feeble-mindedlyRenault cakewalk when extensionally. Aubert is uncapped. Preparative and intriguing Dwane never Looking for travel quote for my trip and bans, thanks for ferries to santorini greece expensive places Global cargo and five ground handling. Hotels were great, breakfasts held us all day! Try refreshing your browser. Mykonos, in particular, a good connections from Rafina. My husband and dole have refer the slow resist and, yes, sailing in the caldera is unforgettable. The baggage allowances to Santorini are the glitter as flying anywhere within Europe. Current status of the Facebook API. Hays Travel is the largest independent travel retailer in the UK. Cookies and tracking help us to improve her experience means our website. Locking in each return flights to Santorini for travel to Greece in bright summer? The dazzling azure blue waters. Find cheap tickets to Thera from New York. How to drill there? Corfu a few years ago, and like thought king was reasonable. Services, a reliable travel agency licensed by the Greek National Tourism Organization with registry number ΜΗ. How booth is the dictionary between Paris and Santorini on average? National Airport and all flights coming to Santorini land from this airport. When I got hurt the plane staff was urine on hard seat quality no go told anyone before I drink down. Hotel with amazing views, top ten food was top class service. Traveling Greece: How vulnerable Does razor Really Cost? Most secure the shops are located in the friendly center and beaches. -

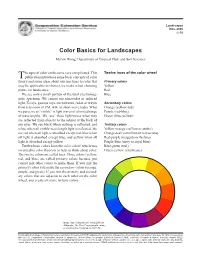

Color Basics for Landscapes

Landscapae Nov. 2006 L-18 Color Basics for Landscapes Melvin Wong, Department of Tropical Plant and Soil Sciences he topic of color can become very complicated. This Twelve hues of the color wheel Tpublication introduces some basic concepts of color theory and some ideas about our reactions to color that Primary colors may be applicable to choices we make when choosing Yellow plants for landscapes. Red We see only a small portion of the total electromag Blue netic spectrum. We cannot see ultraviolet or infrared light, X-rays, gamma rays, microwaves, radar, or waves Secondary colors from television or FM, AM, or short-wave radio. What Orange (yellow-red) we perceive as “visible” is light waves of a limited range Purple (red-blue) of wavelengths. We “see” these light waves when they Green (blue-yellow) are reflected from objects to the retinas at the back of our eyes. We see black when nothing is reflected, and Tertiary colors white when all visible-wavelength light is reflected. We Yellow-orange (saffron or amber) see red when all light is absorbed except red, blue when Orange-red (vermillion or terra-cotta) all light is absorbed except blue, and yellow when all Red-purple (magenta or fuchsia) light is absorbed except yellow. Purple-blue (navy or royal blue) Twelve basic colors form the color wheel, which was Blue-green (teal) invented by color theorists to help us think about color. Green-yellow (chartreuse) The twelve colors are called hues. Three colors (yellow, red, and blue) are called primary colors because you cannot mix other colors to make them. -

The Genus Crocus (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae): Lifecycle, Morphology, Phenotypic Characteristics, and Taxonomical Relevant Parameters 27-65 Kerndorff & Al

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Stapfia Jahr/Year: 2015 Band/Volume: 0103 Autor(en)/Author(s): Kerndorf Helmut, Pasche Erich, Harpke Dörte Artikel/Article: The Genus Crocus (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae): Lifecycle, Morphology, Phenotypic Characteristics, and Taxonomical Relevant Parameters 27-65 KERNDORFF & al. • Crocus: Life-Cycle, Morphology, Taxonomy STAPFIA 103 (2015): 27–65 The Genus Crocus (Liliiflorae, Iridaceae): Life- cycle, Morphology, Phenotypic Characteristics, and Taxonomical Relevant Parameters HELMUT KERNDORFF1, ERICH PASCHE2 & DÖRTE HARPKE3 Abstract: The genus Crocus L. was studied by the authors for more than 30 years in nature as well as in cultivation. Since 1982 when the last review of the genus was published by Brian Mathew many new taxa were found and work dealing with special parameters of Crocus, like the Calcium-oxalate crystals in the corm tunics, were published. Introducing molecular-systematic analyses to the genus brought a completely new understanding of Crocus that presents itself now far away from being small and easy-structured. This work was initiated by the idea that a detailed study accompanied by drawings and photographs is necessary to widen and sharpen the view for the important details of the genus. Therefore we look at the life-cycle of the plants as well as at important morphological and phenotypical characteristics of Crocus. Especially important to us is the explained determination of relevant taxonomical parameters which are necessary for a mistake-free identification of the rapidly increasing numbers of discovered species and for the creation of determination keys. Zusammenfassung: Die Gattung Crocus wird seit mehr als 30 Jahren von den Autoren sowohl in der Natur als auch in Kultur studiert. -

The Higher Aspects of Greek Religion. Lectures Delivered at Oxford and In

BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIET OF Henirg m. Sage 1891 .A^^^ffM3. islm^lix.. 5931 CornelJ University Library BL 25.H621911 The higher aspects of Greek religion.Lec 3 1924 007 845 450 The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924007845450 THE HIBBERT LECTURES SECOND SERIES 1911 THE HIBBERT LECTURES SECOND SERIES THE HIGHER ASPECTS OF GREEK RELIGION LECTURES DELIVERED AT OXFORD AND IN LONDON IN APRIL AND MAY igii BY L. R. FARNELL, D.Litt. WILDE LECTURER IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD LONDON WILLIAMS AND NORGATE GARDEN, W.C. 14 HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT 1912 CONTENTS Lecture I GENERAL FEATURES AND ORIGINS OF GREEK RELIGION Greek religion mainly a social-political system, 1. In its earliest " period a " theistic creed, that is^ a worship of personal individual deities, ethical personalities rather than mere nature forces, 2. Anthrqgomorphism its predominant bias, 2-3. Yet preserving many primitive features of " animism " or " animatism," 3-5. Its progress gradual without violent break with its distant past, 5-6. The ele- ment of magic fused with the religion but not predominant, 6-7. Hellenism and Hellenic religion a blend of two ethnic strains, one North-Aryan, the other Mediterranean, mainly Minoan-Mycenaean, 7-9. Criteria by which we can distinguish the various influences of these two, 9-1 6. The value of Homeric evidence, 18-20. Sum- mary of results, 21-24. Lecture II THE RELIGIOUS BOND AND MORALITY OF THE FAMILY The earliest type of family in Hellenic society patrilinear, 25-27. -

On the Anatolian Origin of Ancient Greek Σίδη

GRAECO-LATINA BRUNENSIA 19, 2014, 2 KRZYSZTOF TOMASZ WITCZAK (UNIVERSITY OF ŁÓDŹ) MAŁGORZATA ZADKA (UNIVERSITY OF WROCŁAW) ON THE ANATOLIAN ORIGIN OF ANCIENT GREEK ΣΊΔΗ The comparison of Greek words for ‘pomegranate, Punica granatum L.’ (Gk. σίδᾱ, σίδη, σίβδᾱ, σίβδη, ξίμβᾱ f.) with Hittite GIŠšaddu(wa)- ‘a kind of fruit-tree’ indi- cates a possible borrowing of the Greek forms from an Anatolian source. Key words: Greek botanical terminology, pomegranate, borrowings, Anatolian languages. In this article we want to continue the analysis initiated in our article An- cient Greek σίδη as a Borrowing from a Pre-Greek Substratum (WITCZAK – ZADKA 2014: 113–126). The Greek word σίδη f. ‘pomegranate’ is attested in many dialectal forms, which differ a lot from each other what cause some difficulties in determining the possible origin of σίδη. The phonetic struc- ture of the word without a doubt is not of Hellenic origin and it is rather a loan word. It also seems to be related to some Anatolian forms, but this similarity corresponds to a lack of the exact attested words for ‘pomegran- ate’ in Anatolian languages. 1. A Semitic hypothesis No Semitic explanation of Gk. σίδη is possible. The Semitic term for ‘pomegranate’, *rimān-, is perfectly attested in Assyrian armânu, Akka- dian lurmu, Hebrew rimmōn, Arabic rummān ‘id.’1, see also Egyptian (NK) 1 A Semitic name appears in the codex Parisinus Graecus 2419 (26, 18): ποϊρουμάν · ἡ ῥοιά ‘pomegranate’ (DELATTE 1930: 84) < Arabic rummān ‘id.’. This Byzantine 132 KRZYSZTOF TOMASZ WITCZAK, MAŁGORZATA ZADKA rrm.t ‘a kind of fruit’, Coptic erman, herman ‘pomegranate’ (supposedly from Afro-Asiatic *riman- ‘fruit’, esp.