Color Basics for Landscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garcinia Hanburyi Guttiferae Hook.F

Garcinia hanburyi Hook.f. Guttiferae LOCAL NAMES English (gamboge tree); German (Gutti,Gummigutt); Thai (rong); Vietnamese (dang hoang) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION An evergreen, small to medium-sized tree, up to 15 m tall, with short and straight trunk, up to 20 cm in diameter; bark grey, smooth, 4-6 mm thick, exuding a yellow gum-resin. Leaves opposite, leathery, elliptic or ovate-lanceolate, 10-25 cm x 3-10 cm, cuneate at base, acuminate at apex, shortly stalked. Flowers in clusters or solitary in the axils of fallen leaves, 4-merous, pale yellow and fragrant, unisexual or bisexual; male flowers somewhat smaller than female and bisexuals; sepals leathery, orbicular, 4-6 mm long, persistent; petals ovate, 6-7 mm long; stamens numerous and arranged on an elevated receptacle in male flowers, less numerous and reduced in female flowers; ovary superior, 4-loculed, with sessile stigma. Fruit a globose berry, 2-3 cm in diameter, smooth, with recurved sepals at the base and crowned by the persistent stigma, 1-4 seeded. Seeds 15-20 mm long, surrounded by a pulpy aril. The gum-resin from G. hanburyi is often called Siamese gamboge to distinguish it from the similar product from the bark of G. morella Desr., called Indian gamboge. The species are closely related, and G. hanburyi has been considered in the past as a variety of G. morella. BIOLOGY Normally it flowers in November and December and fruits from February to April. Agroforestry Database 4.0 (Orwa et al.2009) Page 1 of 5 Garcinia hanburyi Hook.f. Guttiferae ECOLOGY Gamboge tree occurs naturally in rain forest. -

Historical Uses of Saffron: Identifying Potential New Avenues for Modern Research

id8484906 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ISSN : 0974 - 7508 Volume 7 Issue 4 NNaattuurraall PPrrAoon dIdnduuian ccJotutrnssal Trade Science Inc. Full Paper NPAIJ, 7(4), 2011 [174-180] Historical uses of saffron: Identifying potential new avenues for modern research S.Zeinab Mousavi1, S.Zahra Bathaie2* 1Faculty of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, (IRAN) 2Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, (IRAN) E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 20th June, 2011 ; Accepted: 20th July, 2011 ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Background: During the ancient times, saffron (Crocus sativus L.) had Saffron; many uses around the world; however, some of them were forgotten Iran; ’s uses came back into attention during throughout the history. But saffron Ancient medicine; the past few decades, when a new interest in natural active compounds Herbal medicine; arose. It is supposed that understanding different uses of saffron in past Traditional medicine. can help us in finding the best uses for today. Objective: Our objective was to review different uses of saffron throughout the history among different nations. Results: Saffron has been known since more than 3000 years ago by many nations. It was valued not only as a culinary condiment, but also as a dye, perfume and as a medicinal herb. Its medicinal uses ranged from eye problems to genitourinary and many other diseases in various cul- tures. It was also used as a tonic agent and antidepressant drug among many nations. Conclusion(s): Saffron has had many different uses such as being used as a food additive along with being a palliative agent for many human diseases. -

Painting Part 3 1

.T 720 (07) | 157 ) v.10 • pt. 3 I n I I I 6 International Correspondence Schools, Scranton, Pa. Painting By DURWARD E. NICHOLSON Technical Writer, International Correspondence Schools and DAVID T. JONES, B.Arch. Director, School of Architecture and the Building Trades International Correspondence Schools 6227C Part 3 Edition 1 International Correspondence Schools, Scranton, Pennsylvania International Correspondence Schools, Canadian, Ltd., Montreal, Canadc Painting \A jo Pa3RT 3 “I find in life lliat most affairs tliat require serious handling are distasteful. For this reason, I have always believed that the successful man has the hardest battle with himself rather than with the other fellow'. By To bring one’s self to a frame of mind and to the proper energy to accomplish things that require plain DURWARD E. NICHOLSON hard work continuously is the one big battle that Technical Writer everyone has. When this battle is won for all time, then everything is easy.” \ International Correspondence Schools —Thomas A. Buckner and DAVID T. JONES, B. Arch. 33 Director, School of Architecture and the Building Trades International Correspondence Schools B Member, American Institute of Architects Member, Construction Specifications Institute Serial 6227C © 1981 by INTERNATIONAL TEXTBOOK COMPANY Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved International Correspondence Schools > Scranton, Pennsylvania\/ International Correspondence Schools Canadian, Ltd. ICS Montreal, Canada ▼ O (7M V\) v-V*- / / *r? 1 \/> IO What This Text Covers . /’ v- 3 Painting Part 3 1. PlGX OLORS ___________________ ________ Pages 1 to 14 The color of paint depends on the colors of the pigments that are mixed with the vehicle. -

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Color Coat Mixing System

SSTCL 03/09 ® SPECIALS COLOR COAT MIXING SYSTEM FOREIGN CARS MUSTANG THUNDERBIRD CORVETTE FOR TECHNICAL INFORMATION CALL 800-831-1122 SEM PRODUCTS, INC. - 1685 Overview Drive - Rock Hill, SC 29730 www.semproducts.com SPECIALS ® SSTCL COLOR COAT MIXING SYSTEM 03/09 FOREIGN CARS, THUNDERBIRD, MUSTANG AND CORVETTE COLORS ACURA CORVETTE Trim Code Color Name Year SEM No. Trim Code Color Name Year SEM No. N/A BLUE 88-89 4554 N/A AQUA 59 4892 N/A CHARCOAL BLACK 88-89 4555 N/A RED 59-64 4742 N/A IVORY 88-89 4556 N/A FAWN BEIGE 61-62 4947 N/A BURGANDY 88-89 4557 N/A RED 63-64 4835 N/A BEIGE 91 4726 N/A DK BLUE 63-64 4836 N/A VIGOR BEIGE 92 4746 N/A SADDLE 63-64 4837 N/A TAN N/A 5857 N/A CREAMY IVORY N/A 5858 N/A WHITE 64-67 4896 N/A CHARCOAL N/A 5859 N/A RED 65-66 4743 N/A LT SADDLE 65-66 4838 N/A BRIGHT BLUE MET 65-67 4839 N/A DK GREEN 65-67 4840 N/A BRIGHT BLUE 65-67 4737 N/A RED 65-75 4841 ALLANTE (CADILLAC) N/A SILVER 65-75 4842 N/A BLUE 66 4741 Trim Code Color Name Year SEM No. N/A BRIGHT BLUE MET 66 4921 N/A TEAL 67 4843 N/A DK SADDLE 67-70 4844 17 CHARCOAL 87-89 4496 N/A DK BRIGHT BLUE MET 68 4891 63 SADDLE 87-89 4498 N/A TOBACCO 68 4946 71 MAROON 87-89 4497 N/A GUNMETAL 68-69 4934 UCV2-1332 DK GOLD 87 5404 UCV2-1335 DK MAROON 87 5405 N/A SADDLE 68-69 4845 UCV2-1369 NATURAL BEIGE 89-90 5417 N/A BRIGHT BLUE 68-70 4738 UCV2-1370 CHARCOAL 89-90 5410 N/A BRIGHT MET BLUE 68-71 4846 UCV2-1422 DK NATURAL BEIGE N/A 5430 N/A DK GREEN MET 69-71 4847 UCV2-1333 MED MAROON N/A 5429 N/A SADDLE 70 4890 N/A DK BLUE 70-75 4848 N/A BLACK 70-84 1501 N/A BLUE 71 4888 425 OXBLOOD 73-74 4740 N/A OXBLOOD 73-75 4849 AUDI N/A MED SADDLE 73-75 4850 N/A NEUTRAL 74-75 4898 Trim Code Color Name Year SEM No. -

Saffron—Truffle of the Spice World. in the PANTRY Red Gold

IN THE PANTRY red gold Saffron—truffle of the spice world. RED GOLD BY AMY PATUREL 42 The NaTioNal CuliNary review • oCTober 2014 affron is the most expensive spice on earth, and for good reason. It takes more than 200,000 stigmas, picked by Shand from about 80,000 crocus blossoms, to make just 1 pound of the spice. The cost is a whopping $4,500 a pound. Why bother with such a high-maintenance ingredient? Accord- ing to Nirmala Narine, founder of Nirmala’s Kitchen and TV host of Veria Living’s “Nirmala’s Spice World,” there’s no substitute for the musty, honey-like taste saffron provides. “Just a few threads can color and flavor a dish beautifully,” she says. A prized ingredient in Northern Indian, Spanish and Iranian cuisines—the largest saffron-producing regions in the world— saffron can only be harvested during a two-week flowering period, hence, the moniker “red gold.” Yet it has managed to permeate the culinary landscape in the U.S., appearing in everything from ice cubes and cocktails to ice cream and cake. Saffron is loaded with disease-fighting nutrients, such as vitamin C, thiamin and carotenoids. “Its medicinal properties date back centuries,” says Monica Bhide, author of Modern Spice: Inspired Indian Flavors for the Contemporary Kitchen (Simon & ILLUSTRATION CREDIT Craftsmanspace.com ILLUSTRATION Schuster, 2009). In fact, according to ancient medicinal texts, the legendary spice yields a range of benefits, from antidepressant to aphrodisiac. Ask a chef, though, and you’ll learn that saffron’s greatest power lies in its ability to instantly transform an otherwise drab dish. -

Module 3 Imitative and Decorative Arts

TRADE OF PAINTING & DECORATING PHASE 2 Module 3 Imitative and Decorative Arts UNIT: 1 Colour Module 3 – Unit 1 Colour Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Learning Outcomes .................................................................................................. 2 1.0 Pigmental, primary, secondary & tertiary colours ...................................... 3 1.1 The colour circle ......................................................................................... 3 1.2 Primary, secondary and tertiary colours .................................................. 5 2.0 Monochromatic, Analogous & Complementary Colour Harmony ............... 6 2.1 Monochromatic, analogous and complementary colour harmony ...... 6 2.2 Colour in decoration................................................................................... 7 3.0 Produce Secondary and Tertiary Colours By Colour Mixing .......................... 8 3.1 Mixing primary colours to produce secondary ....................................... 8 3.2 Mixing secondary colours to produce tertiary colours .......................... 8 4.0 Tints and Shades ............................................................................................. 9 4.1 Define the terms tints and shades ............................................................ 9 4 2 Mixing tints and shades of various colours ............................................. 9 4.3 Colour terminology .................................................................................. -

A Short History of 18-19Th Century

A SHORT HISTORY OF 18-19TH CENTURY BRITISH HAND-COLOURED PRINTS; WITH A FOCUS ON GAMBOGE, CHROME YELLOW AND QUERCITRON; THEIR SENSITIVITIES AND THEIR IMPACT ON AQUEOUS CONSERVATION TREATMENTS Stacey Mei Kelly (13030862) A Dissertation presented at Northumbria University for the degree of MA in Conservation of Fine Art, 2015 VA0742 Page 1 of 72 Table of Contents List of figures……………………………………………………………………………………...…2 List of tables……………………………………………………………………………………….....2 Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………..………...…3 Research aims, methodology and resources………………………………………………….…....4 1. Aims……………………………………………………………………………………..…...4 2. Research Questions…………………………………………………………………..…...….4 3. Literature review……………………………………………………………………….....….5 4. Case Study Survey………………………………………………………………………..….5 5. Empirical Work……………………………………………………………………………....6 Chapter 1: A Brief History of Hand-coloured Prints in Britain………………………………....6 1.1 The popularity of hand-coloured prints…………………………………………………….....6 1.2 The people behind hand-colouring……………………………………………………..….….9 1.3 Materials and Methods……………………………………………………………………....14 Chapter 2: Yellow Pigments: A focus on Gamboge, Chrome Yellow, and Quercitron……….19 2.1 Why Gamboge, Chrome Yellow, and Quercitron……………………………………….…..19 2.2 Gamboge……………………………………………………………………………….....….20 2.2.1 History…………………………………………………………………………….…....20 2.2.2 Working properties…………………………………………………………………..…21 2.2.3 Physical and chemical properties…………………………………………………..…..21 2.2.4 Methods of -

Color Chart Colorchart

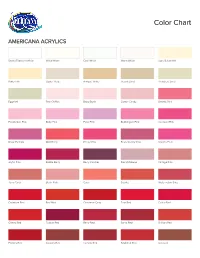

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

Color Themes

COLOR THEMES Let these color moods guide you to create your perfect outdoor living ambiance. VANILLE VELVET ACCENT (VAV) WHITE LINEN ACCENT (WUL) ECRU VELVET ACCENT (EUV) ACCENT WHITE TWIN (WUT) WHITE BASIC (WU) NATURAL WHITE DOT ACCENT (WUT) ACCENT SAND HEAVY (WUL) ECRU BASIC (EU) ACCENT SILVER VELVET (VAV) ACCENT DESERT STONE FLAX (DSF) ACCENT CARAMEL HEAVY BROWN TWIN ACCENT (CAH) (BRT) NATURAL SILVER DOT (NSD) ACCENT COCONUT BASIC (CC) ACCENT DARK BROWN TWIN (DBT) NATURAL ECRU DOT (NED) COLOR THEMES AUBERGINE VELVET ACCENT (AUV) AUBERGINE HEAVY ACCENT (AUH) ACCENT AUBERGINE MESH ACCENT ICE BLUE VELVET (AUM) (IBV) STONE FLAX (SF) LIGHT BLUE DOT ACCENT (LBD) ICE BLUE ACCENT (IB) NATURAL GREY DOT (NGD) ACCENT IRON GREY VELVET (IGV) ACCENT AZURE BLUE HEAVY (AZH) NIGHT BLUE ACCENT (NB) NATURAL GREY DOT (NGD) ACCENT JUNIPER GREEN (JG) ACCENT MOSS HEAVY (MH) FOREST GREEN ACCENT (FG) SAGE LINEN (SL) COLOR THEMES ACCENT DARK BROWN VELVET (DBV) ACCENT ROCK LINEN (ROL) ACCENT SILVER VELVET (SIV) ACCENT PITCH BLACK HEAVY (ZUPH) LINEN CHEVRON ACCENT ROSE UNI (LNC) (RO) ACCENT OLD ROSE (OLR) NATURAL LINEN DOT ACCENT SAFFRON VELVET (SFV) (NLD) ACCENT SAFFRON HEAVY (SFH) ACCENT TERRA VELVET (TEV) YELLOW CROSS ACCENT (YEC) CARMINE HEAVY ECRU LINEN ACCENT (EUL) (CH) CARMINE TWIN ACCENT (CART) FROST LINEN ACCENT SALMON VELVET (FF) (SAV) ACCENT ORANGE DOT (ORD) ACCENT ORANGE CHEVRON (ORC) NATURAL LINEN DOT (NLD). -

Color Book Unformatted

New & Revised - Includes Genesis Heat Set Oils 1 PREFACE There seems to be a mystique about mixing colors. The novice painter procrastinates or delgates this responsibility to a paint manufacturer bu tultimately the day arrives when the painter wants to take control of the palette colours. This can happen only when the painter takes the responsi- bility to learn to mix colour. Mixing colour is very exciting. The knowledge of how to control and create colour is the ultimate in creativity. It is not difficult to master, but it will take time, patience, practice, but most of all desire. The intent of this book is to provide a guide to mixing colour. It is my hope that it will be useful regardless of whether the preferred medium is oil, alkyd, acrylic, watercolour, pastel, pencil or coloured ink. Colour theory applies to all media. All that differs is technique. Colour is so closely interwoven with the other four basic elements of art that it would be impossible to discuss colour without examining its rela- tionship to line, form, texture and space. The importance of colour to har- mony and composition are also inseparable, as are chemistry and tem- perature. Please understand that colour reproduction of a paint mixture in printed form is almost always inaccurate. Every effort has been made to provide the highest quality of photography, colour separations and printing. How- ever, it is not possible to duplicate the myriad nuances of paint with only five colours of printer’s ink. Furthermore, oil reflects the light differently than acrylic. Pencil and watercolour have their own individual properties. -

A Designer's Dozen Newsletter Tips

A DESIGNER S N EWSLETTER TIPS TIPS TOo ENHANCEz n CLARITY Organize the content of your newsletterDD e then use the command in your software to make and into groups: administrator/staff articles the desired portion into all caps. That way, if you 1or columns, grade level/curriculum articles, decide to change it to upper and lower case later, extracurricular groups/events/sports, parent you don’t have to retype it. group/organization articles or columns, items that need action (such as forms to be filled out See how you first Reverses are very effective, and returned, workshop flyers that ask for looked at this reverse? but use only in a few small areas. They are a good choice advance registration, etc.; e careful that you don’t You might want to use a 4 have two things on back-to-back pages that need reverse for a short item for short items that you want to call to be filled out and returned to different places) you want a response to, attention to. Use a bold weight for such as a call for volun- the white type so that it doesn’t fill in and general informational items from outside- teers or a lost and found the-school sources (such as District letters reminder. Notice how when copied, and you may want to regarding bus safety, lunch information flyer both the subhead and increase the point size of the type as body of this item are well. Set up your text block to have from SoDexHo, parenting information newsletter bolder than the typefaces that the school subscribes to, etc.