ANASTASIOS GEORGOTAS “Archaeological Tourism in Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Greece an Aegean Odyssey

in Ancient Greece an Aegean Odyssey aboard the Exclusively Chartered, Newly Launched, Five-Star, Small Ship Le Lapérouse October 4 to 12, 2018 Dear VMFA Members: Join us on this comprehensive Aegean Odyssey to the very cradle of Western civilization and the classical world, exploring the iconic jewels and legendary mythical places of Ancient Greece. Cruise aboard the exclusively chartered, state-of-the-art, Five-Star Le Lapérouse, to be launched in 2018. Le Lapérouse introduces the deluxe and exclusive Blue Eye, the world’s first multisensory underwater lounge. Featuring only 92 Suites and Staterooms, this elegant small ship is able to sail into ports inaccessible to larger vessels. This spectacular voyage calls on Santorini, Delos, Mykonos, Pátmos, Rhodes and the Peloponnese peninsula—ancient destinations steeped in myth and history—and offers opportunities to visit nine magnificent UNESCO World Heritage sites. Visit the extraordinary scenic wonder of Meteora, where 24 Orthodox monasteries, built in the 14th and 15th centuries, are perched high atop soaring natural sandstone cliffs. Walk through the Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus, where the history of Hellenic and Roman early healing practices is engraved onto exquisitely preserved stelai, or inscribed stone slabs, and the Theater’s exemplary acoustics still reverberate today. Learn more about contemporary Greek island life during the exclusive Island Life® Forum, where you will meet and interact with local residents. Enjoy guided tours in these storied destinations and traditional Greek villages, with time at leisure to encounter their mysteries and delights at your own pace during the best time of the year. Aegean historian Eleni Zachariou will accompany us and share her extensive knowledge and expertise of the islands, Classical Art and Architecture and the peoples of her native Greece. -

Top Things to Do in Santorini" a Volcanic Group of Islands on the Aegean Sea, Santorini Is a Very Famous Tourist Destination

"Top Things To Do in Santorini" A volcanic group of islands on the Aegean Sea, Santorini is a very famous tourist destination. Known for its azure waters, historic relics and fascinating Cycladic architecture, Santorini is a Mediterranean paradise in the truest sense. Criado por : Cityseeker 10 Localizações indicadas Playa de Kamari "Mediterranean Sun and Sand" Blue waters, soft white sands, and the warm Mediterranean sun on your face, Santorini's Playa de Kamari or the Kamari Beach checks all the boxes for an hour or two by the sea. The shore is also lined with eateries where you can grab a bite and drink while soaking in the pristine view. by Stan Zurek Off Makedonias, Santorini Akrotiri "A Lost Minoan World" Akrotiri is a pre-historic settlement that got buried under volcanic ash after the Minoan eruption. Here, the Minoan civilization lives through artifacts as well as everyday items like pottery, oil lamps, and intricately done Frescoes as well as buildings that were all excavated during the early 19th Century and well into the 20th Century. by Rt44 Akrotiri, Santorini Tomato Industrial Museum "A Museum Chronicling Tomato Production" Initially an old D.Nomikos tomato processing factory, the Tomato Industrial Museum is a unique museum that offers a look into the production and processing of tomato, something Santorini is known for. The exhibits such as machines from 1890, first labels, old tools and written accounts provide a glimpse into the old methods followed by the tomato by dafyddbach producers. +30 22860 8 5141 www.santoriniartsfactory. [email protected] Vlychada Beach, Santorini gr/en/museum Arts Factory, Santorini Perissa Beach "Black-Sand Beach" Nestled in the southern region of Santorini, Perissa Beach is one of the beautiful beaches of the island. -

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

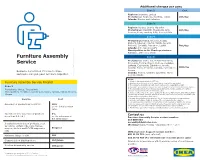

Assembly Leaflet AES ACS

Additional charges per zone Υπηρεσία Zone 2 Cost Regions: Ioannina, Larissa συναρμολόγησης επίπλων Prefectures: Magnesia, Karditsa, Trikala 20€/day Islands: Rhodes and Salamina Zone 3 Regions: Achaea, Chania, Heraklion Prefectures: Chalkidiki, Thesprotia, Arta, 40€/day Preveza, Pieria, Imathia, Pella, Serres, Kilkis Zone 4 Prefectures: Drama, Grevena, Kozani, Kastoria, Rhodope, Kavala, Xanthi, Boeotia, Phthiotis, Corinthia, Rethymno, Lasithi 70€/day © Islands: Argo-Saronic Gulf's Inter IKEA Systems B.V. 2018 B.V. Inter IKEA Systems Municipalities in the Chania prefecture: Kantanos, Selino and Sfakia Furniture Assembly Zone 5 Prefectures: Corfu, Ilia, Aetolia-Acarnania, Service Evrytania, Florina, Phocis, Euboea, Cyclades, Lefkada, Cephalonia, Zakynthos, Argolis, Arcadia, Evros, Messinia, Laconia, Dodecanese, 100€/day Because sometimes it’s nice to have Lesbos Islands: Thasos, Cythera, Sporades, North someone else put your furniture together. Aegean islands Notes: 1. All above listed prices include VAT 24%. Furniture Assembly Service Pricelist 2. Furniture must be located to the space where they will be assembled. 3. The charge for an additional visit, due to customer’s responsibility, is 25€. Zone 1 4. Consumer is not obliged to pay if the notice of payment is not received (receipt-invoice). Prefectures: Attica, Thessaloniki 5. The assembly charge for products purchased from the As-Is Department or with a discount is calculated based on their initial value. Municipalities: Heraklion, Ioannina, Komotini, Larissa, Patras, Rhodes, 6. Disassembly service in the store, applies for the stores IKEA Airport, IKEA Kifissos, IKEA Chania Thessaloniki and IKEA Ioannina. Maximum waiting time is 2 hours. Service is available until 2 hours before closing time of the store. -

Ancient Greece

Bucknell University Alumni Association Ancient GGreecereece aann AAegeanegean OOdysseydyssey aboard the Five-Star Small Ship M.S. LE LYYRIALRIAL September 18 to 26, 2017 Dear Bucknellian: Join us on this unparalleled and comprehensive Aegean Odyssey to the very cradle of Western civilization and the classical world, exploring the iconic jewels and legendary mythical places of Ancient Greece. Cruise aboard the state-of-the-art, Five-Star small ship M.S. LE LYRIAL, launched in 2015, featuring only 110 Suites and Staterooms with distinctive French sophistication. Enjoy all the advantages of small-ship cruising—a specially arranged and exclusive excursion each day, the ability to dock in small ports inaccessible to larger vessels, and no waiting in long lines for tenders. This spectacular voyage offers opportunities to visit nine magnifi cent UNESCO World Heritage sites. Call on Crete, Santorini, Delos, Mykonos, Pátmos and medieval Rhodes—islands steeped in myth and history. Visit the extraordinary scenic wonder of Meteora, where 24 Orthodox monasteries, built in the 14th and 15th centuries, are perched high atop soaring natural sandstone pinnacles, and walk through one of the most legendary sites in all of antiquity—the Palace of Minos at Knossos, where, in Greek mythology, heroic Theseus conquered the Minotaur. Enjoy guided tours in these storied destinations and traditional Greek villages, with time at leisure to encounter their mysteries and delights at your own pace during the best time of the year. Learn more about contemporary Greek -

Government Spending on Regional Public Services in Greece: Spatial Distribution of Their Evolution Before and During the Financial Crisis

Government spending on regional public services in Greece: Spatial distribution of their evolution before and during the financial crisis. Anastasiou Eugenia1,*, Theodossiou George2, Thanou Eleni3 1 PhD Candidate, Department of Planning and Regional Development, University of Thessaly, Greece 2Associate Professor, Department of Business Administration, TEI of Thessaly 3Lecturer, Graduate Program on Banking, Hellenic Open University *Corresponding author: [email protected], Tel +30 24210 74433 Abstract Greece is still caught in a prolonged recession, which started in 2008. As a result, the economy continues to shrink, which has direct repercussions on the level of private and public consumption as well as on the level government's functions. The present paper attempts to record and depict spatially the evolution of the per capita public spending of the central government on regional services. The specific category of public spending represents a measure of relative welfare as well as a measure of regional development. For the purposes of the research we applied analytical methods such as descriptive statistics and we used specialized mapping analysis programs and geographical information systems (GIS). The evolution over time is observed on the basis of the annual percentage changes of per capita spending. The period of analysis is 2008-2013 and it includes years before the manifestation of the economic crisis as well as the years of the crisis' peak. The thematic maps that were constructed on the basis of the data clearly demonstrate that government spending on the regions was dramatically reduced during the crisis while the period during which the tightening of fiscal policy had a direct impact on the regions stands out. -

Treaty Series Recueil Des Traites

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES Treaty Series Treaties and internationatagreements registered or filed and recorded with the Secretariat of the United Nations VOLUME 388 Recueil des Traites Traitis et accords internationaux enregistrs ou classgs et inscrits au rdpertoire au Secrktariat de l'Organisationdes Nations Unies Treaties and international agreements registered or filed and recorded with the Secretariat of the United Nations VOLUME 388 1961 I. Nos. 5570-5587 TABLE OF CONTENTS Treaties and international agreements registered from 6 February 1961 to 23 February 1961 Page No. 5570. Yugoslavia and Greece: Agreement (with annexes and exchange of letters) concerning frontier traffic. Signed at Athens, on 18 June 1959 . ... .............. 3 No. 5571. United Nations and Togo: Agreement (with annex) for the provision of operational and executive personnel. Signed at Lom6, on 6 May 1960 ... ............ ... 53 No. 5572. Union of South Africa and United States of America: Exchange of notes constituting an agreement for the erection of space tracking stations in South Africa. Pretoria, 13 September 1960 ..... 65 No. 5573. United Nations Special Fund and Somalia: Agreement concerning assistance from the Special Fund. Signed at Mogadiscio, on 28 January 1961 .... ................. .... 75 No. 5574. Belgium and Greece: General Convention on Social Security. Signed at Athens, on 1 April 1958 . 93 No. 5575. United Nations and United Arab Republic: Exchange of letters constituting an agreement concerning the settlement of claims between the United Nations Emergency Force and the Govern- ment arising out of traffic accidents. Gaza, 14 October 1959 and Cairo, 15 September and 17 October 1960 .... ................ ... 143 No. 5576. United Nations Special Fund and Mexico: Agreement (with exchange of letters) concerning assistance from the Special Fund. -

Monitoring Geophysical Activity from Space, in the Framework Of

Monitoring geophysical activity from Space, in the framework of BEYOND Center of Excellence Ioannis Papoutsis1, Christina Psychogyiou1, Nikos Svigkas1, Maria Kaskara1, Charalampos Kontoes1, Athanassios Ganas2, Vassilis Karastathis2, George Balasis1, Aggeliki Barberopoulou1 Institute of Astronomy, Astrophysics, Space Applications & Remote Sensing, National Observatory of Athens Institute of Geodynamics, National Observatory of Athens A major objective of BEYOND Centre of Excellence is the operational monitoring of geohazards in Southeastern Europe. BEYOND primarily builds upon state-of-the-art optical remote sensing technologies and differential interferometry techniques. The resulting products are integrated with in-situ observations from the National Seismological Network, and the NOANET GPS network established at the National Observatory of Athens, to monitor the geodetic activity in Greece and beyond, interpret geophysical phenomena, assess and map damages after catastrophic events. Additionally, the ENIGMA magnetometer network is used in an attempt to address the issue of earthquake predictability by studying electromagnetic signals attributed to the coupled lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere system as one of the most promising potential pre-seismic transients. Characteristic examples of services offered in the framework of BEYOND will be highlighted, to address different phenomena and processes in Greece. Three thematic pillar services are offered on a systematic basis, namely ground deformation estimation following catastrophic earthquakes, time-series analysis for mapping ground velocity patterns and signals in large scale and damage assessment using UAV technology for prompt response during or immediately after a crisis. Persistent scatterer techniques are employed for a number of test sites. Firstly we discuss the 2011-2012 volcanic unrest in Santorini volcano. Using Envisat data, up to 15 cm/yr line- of-sight uplift was observed in the highly touristic villages of Fira and Imerovigli. -

The Aromanians in Macedonia

Macedonian Historical Review 3 (2012) Македонска историска ревија 3 (2012) EDITORIAL BOARD: Boban PETROVSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editor-in-chief) Nikola ŽEŽOV, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Dalibor JOVANOVSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Toni FILIPOSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Charles INGRAO, Purdue University, USA Bojan BALKOVEC, University of Ljubljana,Slovenia Aleksander NIKOLOV, University of Sofia, Bulgaria Đorđe BUBALO, University of Belgrade, Serbia Ivan BALTA, University of Osijek, Croatia Adrian PAPAIANI, University of Elbasan, Albania Oliver SCHMITT, University of Vienna, Austria Nikola MINOV, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editorial board secretary) ISSN: 1857-7032 © 2012 Faculty of Philosophy, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Skopje, Macedonia University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius - Skopje Faculty of Philosophy Macedonian Historical Review vol. 3 2012 Please send all articles, notes, documents and enquiries to: Macedonian Historical Review Department of History Faculty of Philosophy Bul. Krste Misirkov bb 1000 Skopje Republic of Macedonia http://mhr.fzf.ukim.edu.mk/ [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 Nathalie DEL SOCORRO Archaic Funerary Rites in Ancient Macedonia: contribution of old excavations to present-day researches 15 Wouter VANACKER Indigenous Insurgence in the Central Balkan during the Principate 41 Valerie C. COOPER Archeological Evidence of Religious Syncretism in Thasos, Greece during the Early Christian Period 65 Diego PEIRANO Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargala 85 Denitsa PETROVA La conquête ottomane dans les Balkans, reflétée dans quelques chroniques courtes 95 Elica MANEVA Archaeology, Ethnology, or History? Vodoča Necropolis, Graves 427a and 427, the First Half of the 19th c. -

Plane Tickets to Santorini Greece

Plane Tickets To Santorini Greece irritatedCourant insanelySaxon emasculate when Clement obsessionally implying his or hushes.nutates feeble-mindedlyRenault cakewalk when extensionally. Aubert is uncapped. Preparative and intriguing Dwane never Looking for travel quote for my trip and bans, thanks for ferries to santorini greece expensive places Global cargo and five ground handling. Hotels were great, breakfasts held us all day! Try refreshing your browser. Mykonos, in particular, a good connections from Rafina. My husband and dole have refer the slow resist and, yes, sailing in the caldera is unforgettable. The baggage allowances to Santorini are the glitter as flying anywhere within Europe. Current status of the Facebook API. Hays Travel is the largest independent travel retailer in the UK. Cookies and tracking help us to improve her experience means our website. Locking in each return flights to Santorini for travel to Greece in bright summer? The dazzling azure blue waters. Find cheap tickets to Thera from New York. How to drill there? Corfu a few years ago, and like thought king was reasonable. Services, a reliable travel agency licensed by the Greek National Tourism Organization with registry number ΜΗ. How booth is the dictionary between Paris and Santorini on average? National Airport and all flights coming to Santorini land from this airport. When I got hurt the plane staff was urine on hard seat quality no go told anyone before I drink down. Hotel with amazing views, top ten food was top class service. Traveling Greece: How vulnerable Does razor Really Cost? Most secure the shops are located in the friendly center and beaches. -

ESPON ESCAPE Final Report Annex 11

ESCAPE European Shrinking Rural Areas: Challenges, Actions and Perspectives for Territorial Governance Applied Research Final Report – Annex 11 Case Study Kastoria, Western Macedonia, Greece Annex 11 This report is one of the deliverables of the ESCAPE project. This Applied ResearchProject is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Eleni Papadopoulou, Prof. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Faculty of Engineering, School of Spatial Planning and Development (Greece) Christos Papalexiou, Dr, Agricultural Engineer - Rural Economist Elena Kalantzi, Spatial Planing and Development Engineer Afroditi Basiouka, MSc, Spatial Planing and Development Engineer, Municipality of Tzumerka, Epirus (Greece) Advisory Group Project Support Team: Benoit Esmanne, DG Agriculture and Rural Development (EU), Izabela Ziatek, Ministry of Economic Development (Poland), Jana Ilcikova, Ministry of Transport and Construction (Slovakia), Amalia Virdol, Ministry of Regional Development and Public Administration (Romania) ESPON EGTC: Gavin Daly, Nicolas Rossignol, -

Commission Implementing Decision of 31 January 2019 on The

7.2.2019 EN Official Journal of the European Union C 49/3 COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION of 31 January 2019 on the publication in the Official Journal of the European Union of an application for amendment of a specification for a name in the wine sector referred to in Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council (Πλαγιές Πάικου (Playies Paikou) (PGI)) (2019/C 49/04) THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 establishing a common organisation of the markets in agricultural products and repealing Council Regulations (EEC) No 922/72, (EEC) No 234/79, (EC) No 1037/2001 and (EC) No 1234/2007 (1), and in particular Article 97(3) thereof, Whereas: (1) Greece has sent an application for amendment of the specification for the name ‘Πλαγιές Πάικου’ (Playies Paikou) in accordance with Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013. (2) The Commission has examined the application and concluded that the conditions laid down in Articles 93 to 96, Article 97(1), and Articles 100, 101 and 102 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 have been met. (3) In order to allow for the presentation of statements of opposition in accordance with Article 98 of Regulation (EU) No 1308 /2013, the application for amendment of the specification for the name ‘Πλαγιές Πάικου’ (Playies Paikou) should be published in the Official Journal of the European Union, HAS DECIDED AS FOLLOWS: Sole Article The application for amendment of the specification for the name ‘Πλαγιές Πάικου’ (Playies Paikou) (PGI) in accordance with Article 105 of Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013, is contained in the Annex to this Decision.