The Decipherment: People, Process, Challenges Anna P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

A Computational Translation of the Phaistos Disk Peter Revesz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln CSE Conference and Workshop Papers Computer Science and Engineering, Department of 10-1-2015 A Computational Translation of the Phaistos Disk Peter Revesz University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cseconfwork Part of the Comparative and Historical Linguistics Commons, Computational Linguistics Commons, Computer Engineering Commons, Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons, Language Interpretation and Translation Commons, and the Other Computer Sciences Commons Revesz, Peter, "A Computational Translation of the Phaistos Disk" (2015). CSE Conference and Workshop Papers. 312. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cseconfwork/312 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Computer Science and Engineering, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in CSE Conference and Workshop Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Mathematical Models and Computational Methods A Computational Translation of the Phaistos Disk Peter Z. Revesz several problems. First, a symbol may be interpreted as Abstract— For over a century the text of the Phaistos Disk denoting many different objects. Second, the depicted object remained an enigma without a convincing translation. This paper could have many synonyms in the native language. Third, presents a novel semi-automatic translation method -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Texts from De.Wikipedia.Org, De.Wikisource.Org

Texts from http://www.gutenberg.org/files/13635/13635-h/13635-h.htm, de.wikipedia.org, de.wikisource.org BRITISH AND GERMAN AUTHORS AND Contents: INTELLECTUALS CONFRONT EACH OTHER IN 1914 1. British authors defend England’s war (17 September) The material here collected consists of altercations between British and German men of letters and professors in the first 2. Appeal of the 93 German professors “to the world of months of the First World War. Remarkably they present culture” (4 October 1914) themselves as collective bodies and as an authoritative voice on — 2a. German version behalf of their nation. — 2b. English version The English-language materials given here were published in, 3. Declaration of the German university professors (16 and have been quoted from, The New York Times Current October 1914) History: A Monthly Magazine ("The European War", vol. 1: — 3a. German version "From the beginning to March 1915"; New York: The New — 3b. English version York Times Company 1915), online on Project Gutenberg (www.gutenberg.org). That same source also contains many 4. Reply to the German professors, by British scholars interventions written à titre personnel by individuals, including (21 October 1914) G.B. Shaw, H.G. Wells, Arnold Bennett, John Galsworthy, Jerome K. Jerome, Rudyard Kipling, G.K. Chesterton, H. Rider Haggard, Robert Bridges, Arthur Conan Doyle, Maurice Maeterlinck, Henri Bergson, Romain Rolland, Gerhart Hauptmann and Adolf von Harnack (whose open letter "to Americans in Germany" provoked a response signed by 11 British theologians). The German texts given here here can be found, with backgrounds, further references and more precise datings, in the German wikipedia article "Manifest der 93" and the German wikisource article “Erklärung der Hochschullehrer des Deutschen Reiches” (in a version dated 23 October 1914, with French parallel translation, along with the names of all 3000 signatories). -

December 4, 1954 NATURE 1037

No. 4440 December 4, 1954 NATURE 1037 COPLEY MEDALLISTS, 1915-54 is that he never ventured far into interpretation or 1915 I. P. Pavlov 1934 Prof. J. S. Haldane prediction after his early studies in fungi. Here his 1916 Sir James Dewar 1935 Prof. C. T. R. Wilson interpretation was unfortunate in that he tied' the 1917 Emile Roux 1936 Sir Arthur Evans word sex to the property of incompatibility and 1918 H. A. Lorentz 1937 Sir Henry Dale thereby led his successors astray right down to the 1919 M. Bayliss W. 1938 Prof. Niels Bohr present day. In a sense the style of his work is best 1920 H. T. Brown 1939 Prof. T. H. Morgan 1921 Sir Joseph Larmor 1940 Prof. P. Langevin represented by his diagrams of Datura chromosomes 1922 Lord Rutherford 1941 Sir Thomas Lewis as packets. These diagrams were useful in a popular 1923 Sir Horace Lamb 1942 Sir Robert Robinson sense so long as one did not take them too seriously. 1924 Sir Edward Sharpey- 1943 Sir Joseph Bancroft Unfortunately, it seems that Blakeslee did take them Schafer 1944 Sir Geoffrey Taylor seriously. To him they were the real and final thing. 1925 A. Einstein 1945 Dr. 0. T. Avery By his alertness and ingenuity and his practical 1926 Sir Frederick Gow 1946 Dr. E. D. Adrian sense in organizing the Station for Experimental land Hopkins 1947 Prof. G. H. Hardy Evolution at Cold Spring Harbor (where he worked 1927 Sir Charles Sherring- 1948 . A. V. Hill Prof in 1942), ton 1949 Prof. G. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

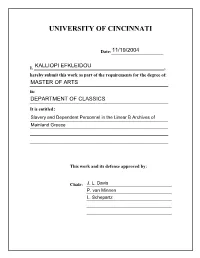

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Classical Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2004 by Kalliopi Efkleidou B.A., Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2001 Committee Chair: Jack L. Davis ABSTRACT SLAVERY AND DEPENDENT PERSONNEL IN THE LINEAR B ARCHIVES OF MAINLAND GREECE by Kalliopi Efkleidou This work focuses on the relations of dominance as they are demonstrated in the Linear B archives of Mainland Greece (Pylos, Tiryns, Mycenae, and Thebes) and discusses whether the social status of the “slave” can be ascribed to any social group or individual. The analysis of the Linear B tablets demonstrates that, among the lower-status people, a social group that has been generally treated by scholars as internally undifferentiated, there were differentiations in social status and levels of dependence. A set of conditions that have been recognized as being of central importance to the description of the -

Boylan, Patrick J

BSHS Monographs publishes work of lasting scholarly value that might not otherwise be made available, and aids the dissemination of innovative projects advancing scholarship or education in the field. 13. Chang, Hasok and Jackson, 06. Morris, PJT, and Russell, CA; Catherine (eds.). 2007. An Smith, JG (ed.). 1988. Archives of Element of Controversy: The Life the British Chemical Industry, of Chlorine in Science, Medicine, 1750‐1914: A Handlist. Technology and War. ISBN 0‐0906450‐06‐3. ISBN: 978‐0‐906450‐01‐7. 05. Rees, Graham. 1984. Francis 12. Thackray, John C. (ed.). 2003. Bacon's Natural Philosophy: A To See the Fellows Fight: Eye New Source. Witness Accounts of Meetings of ISBN 0‐906450‐04‐7. the Geological Society of London 04. Hunter, Michael. 1994. The and Its Club, 1822‐1868. 2003. Royal Society and Its Fellows, ISBN: 0‐906450‐14‐4. 1660‐1700. 2nd edition. 11. Field, JV and James, Frank ISBN 978‐0‐906450‐09‐3. AJL. 1997. Science in Art. 03. Wynne, Brian. 1982. ISBN 0‐906450‐13‐6. Rationality and Ritual: The 10. Lester, Joe and Bowler, Windscale Inquiry and Nuclear Peter. E. Ray Lankester and the Decisions in Britain. Making of Modern British ISBN 0‐906450‐02‐0 Biology. 1995. 02. Outram, Dorinda (ed.). 2009. ISBN 978‐0‐906450‐11‐6. The Letters of Georges Cuvier. 09. Crosland, Maurice. 1994. In reprint of 1980 edition. the Shadow of Lavoisier: ISBN 0‐906450‐05‐5. ISBN 0‐906450‐10‐1. 01. Jordanova, L. and Porter, Roy 08. Shortland, Michael (ed.). (eds.). 1997. Images of the Earth: 1993. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 8913622 A physically-based simulation approach to three-dimensional computer animation Caldwell, Craig Bemreuter, Ph.D. -

Maritime Matters in the Linear B Tab Lets

MARITIME MATTERS IN THE LINEAR B TAB LETS "Unfortunately, we know nothing about the nature and type of organization of the Aegean seaborne trade" I_ Even in the two years that this statement has been in print, it has become hyperbolic, if not untrue, especially in regard to trade with Minoan Crete 2. It is my aim in this paper to A. ALTMAN, "Trade Between the Aegean and the Levant in the Late Bronze Age: Some Neglected Questions", in M. HEL TZER and E. LIPINSKI eds., Society and Economy in the Eastern Mediterranean (Leuven 1988), 231. I use the following abbreviated references: AR : Archaeological Reports; Col/Myc: E. RISCH and H. MO&ESTEIN eds., Colloquium Mycenaeum (Geneva 1979); DicEt: P. Chantraine, Dictionnaire erymologique de la langue grecque (Paris 1968-1980); DMic: F. AURA JORRO, Diccionario Micenico (Madrid 1985); Docs2: M. VENTRIS and J. CHADWICK, Documents in Mycenaean Greek, 2nd ed. (Cambridge 1973); Evidence/or Trade: G.F. BASS, "Evidence for Trade from Bronze Age Shipwrecks", in N.H. Gale and Z.A. Stos-Gale eds., Science and Archaeology: Bronze Age Trade in the Mediterranean (SIM A fonhcoming); lnterp: L.R. PALMER, The Interpretation of Mycenaean Greek Texts (Oxford 1963); LCE: R. TREUIL, P. DARCQUE, J.-C. POURSAT, G. TOUCHAIS, Les civilisa1ions egeennes du Neolithique et de /'Age du Bronze (Paris 1989); MG: R. HOPE SIMPSON, Mycenaean Greece (Park Ridge, NJ 1981); Muster: 1. CHADWICK, "The Muster of the Pylian Fleet", in P.H. ILIEVSKI and L. CREPAJAC eds., Tractata Mycenaea (Skopje 1987), 75-84; MycStud: E.L. BENNETT, Jr. ed., Mycenaean Studies (Madison 1964); Nature of Minoan Trade: M.H. -

Sir Arthur Evans and the Minoan Myth: the Creation of Ancient Cretan Culture

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 4-15-2021 Sir Arthur Evans and the Minoan Myth: The Creation of Ancient Cretan Culture Madeleine McCracken Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation McCracken, Madeleine, "Sir Arthur Evans and the Minoan Myth: The Creation of Ancient Cretan Culture" (2021). Honors Theses. 1715. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1715 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. m Sir Arthur Evans and the Minoan Myth: The Creation of Ancient Cretan Culture By Madeleine McCracken A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford, MS May 2021 Approved By ______________________________ Advisor: Professor Aileen Ajootian ______________________________ Reader: Professor Jacqueline Dibiasie ______________________________ Reader: Professor Tony Boudreaux i m © 2021 Madeleine Louise McCracken ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii m DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to everyone who guided and encouraged me throughout the year. Thank you. iii m ABSTRACT MADELEINE MCCRACKEN: Sir Arthur Evans and the Creation of the Minoan Myth This paper explores the excavations conducted in the early 20th century by Sir Arthur Evans at the site of Knossos on the island of Crete. An analysis of Evans’ humanitarian and journalistic work in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the late 19th century sets the tone for the paper. -

SPRING MEETING PLANS for PAAH 7, a Collaborative Issue With

NO. 78 MARCH 1999 information is received, a task that importance." Let me add that Sheila PRESIDENT’S Konrad has volunteered to continue. Hooker, James' widow, is very CORNER Please send changes or additions to him pleased. Our most recent publication, the at [email protected]. New printed On the subject of our publications, second edition of The Directory of copies will be created as needed. we have reason to claim some fair Ancient Historians in the United States, Another recent publication is also financial success: royalties last year should now be in your hands. It available: James Hooker's essays on were $860.00, a chunk of which came represents three years of effort, the The Coming of the Greeks, our second from Jack Cargill's privately-funded assistance of many including the special volume. It is available through Handbook for Ancient History compilers of the original directory, Regina Books at $9.00 for members, Classes. Richard Talbert and Robert Wallace, $13.95 for non-members. Briggs Our list should continue to grow. and the coordination provided by Twyman, among the first to obtain a Gene Borza has delivered his Konrad Kinzl. Our plan is to update copy, wrote "The reproduction of manuscript for PAAH 6 on Macedon the entries on the electronic version as Hooker's articles should prove of great before Alexander. Readers have copies; now we must examine the state of the treasury. Next year may provide the contents SPRING MEETING PLANS for PAAH 7, a collaborative issue with the provisional title Current Concepts The 1999 annual meeting of the Association will be held in New York on May 7-9 at and the Study of Ancient History.