A Cinematic Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spanish Women Composers, a Critical Equation Susan Campos

Between Left-led Republic and Falangism? Spanish Women Composers, a Critical Equation Susan Campos Fonseca Director, Women’s Studies in Music Research Group Society for Ethnomusicology (SIBE), Spain A Critical Equation The nature of this research depends on the German concept Vergangenheitsbewältigung, a term consisting of the words Vergangenheit (past) and Bewältigung (improvement), equivalent to “critical engagement with the past.”1 This term is internationalized in the sense that it express the particular German problem regarding the involvement that the generations after Second World War had with the Nazis crimes. Germany forced itself to take a leading role in addressing critically their own history. Spain offered in this area for a long time a counterexample. The broader debate on the valuation of the recent past carried out both in politics and in public life only began at the turn of the century, for example in the legislative period from 2004 to 2008 with the “Ley de Memoria” (Memory Law), which sought moral and material compensation for victims of Civil War and Dictatorship.2 But the law is a consequence not a cause. 1 W. L. Bernecker & S. Brinkmann, Memorias divididas. Guerra civil y franquismo en la sociedad y la política españolas (1936-2008) (Madrid: ABADA Ed./Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, 2009). [Author’s translation.] 2 Ibid., 8. Therefore, I present this research as a work in progress,3 because today bio- bibliographies devoted to recover the legacy of Spanish women composers during this period show an instrumental absence of this type of analysis, and instead have favored nationalistic appreciations. -

Download the Events Brochure

1 THE EXCLUSIVE WORLD OF CHAPLIN FOR YOUR EVENTS 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENT 5 12 26 Chaplin is back Backstage Easy Street & The Circus 6 14 28 Infinite possibilities The Manoir: A space rich with emotion Hollywood Boulevard 9 22 30 A site covering 4 hectares Le Studio Restaurant: The Tramp 10 24 35 Welcome to Chaplin’s World ! The Cinema Practical information 36 Contact 4 5 CHAPLIN’S CHAPLIN WORLD IS BACK CHAPLIN’S WORLD ABSOLUTELY UNIQUE Immerse yourself in the universe of Charlie Chaplin and experience the emotion of encountering one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. harlie Chaplin is a legend, known and entertaining museum designed to plunge you Cloved all over the planet. His positive aura into the private and Hollywood life of Charlie continues to shine on the world – the very Chaplin, allowing you to discover both the man world he portrayed through his comic and and the artist: Charlie and the Tramp. Play human vision. The Tramp, his iconic character, among sets from his movies and make one of has brought, and continues to bring laughter the most beautiful spots in the Riviera your own to millions of people. Situated between lake private paradise. and mountain, Chaplin’s World By Grévin is an 6 7 INFINITE POSSIBILITIES haplin’s World By Grévin offers the PRESTIGIOUS SPACES AT THE HEART OF Crental of the entire site or certain A UNIQUE CULTURAL DESTINATION FOR: areas for the organization of private receptions, events, and activities for PROFESSIONAL EVENTS INCLUDING individuals and companies. These events Presentations and assemblies can be paired with museum visits. -

Programa Fernando Remacha

FERNANDO REMACHA PODEROSO SILENCIO.TRAYECTORIA VITAL Y MUSICAL DE FERNANDO REMACHA (1898-1984) ¡Poderoso silencio, poderoso silencio! Sube el mar hasta ya ahogarnos en su terrible estruendo silencioso! Blas de Otero Debemos a Álvaro Zaldívar la brillante analogía entre estos versos de Otero y la actitud de Remacha en la posguerra, cuando sobrevivía en la situación que se ha dado en llamar exilio interior. Al elegir este camino oscuro, frente a las posibilidades de la huida o de posturas de despreocupado esteticismo –pro- puesta ensimismada las llama Zaldívar, encontrando su paradigma en textos como El arte desde su esencia de Camón Aznar– Remacha acabaría encon- trando un lugar crucial en la música española del siglo XX, como intentare- mos establecer en este texto. Pero, a la vez, tendría que pagar un alto precio de aislamiento, un eclipsamiento de su figura que durante decenios le ha con- 3 denado a ser poco más que una cita marginal cuando se menciona al Grupo de Madrid o de los Ocho. “En realidad éramos cinco músicos: Salvador Bacarisse, Gustavo Pittaluga, Ro- dolfo Halffter, Julián Bautista y yo. Cada uno teníamos nuestra propia técnica. Nos veíamos con frecuencia en Foto Unión Radio”. Esto es lo que Remacha recordaba de la Generación del 27 cuando se le preguntó casi cincuenta años más tarde. No sabemos si el olvido de García Ascot, Mantecón y Ernesto Halffter –miembros también del Grupo de los Ocho– fue un despiste del pe- riodista, pero la nómina coincide con los cinco compositores de la fotografía tomada en 1931 en un despacho de Unión Radio. -

Julian Bautista

JULIAN BAUTISTA POR Roberto García Morillo PRONTO hará diez años que se encuentra radicado en la Ar gentina el prestigioso compositor español Julián Bautista, quien, a diferencia de Manuel de Falla (el que, desde su llegada al país has ta su muerte, en Alta Gracia, permaneció prácticamente al margen del movimiento musical del país, salvo algunas ocasionales apari ciones en público), ha intervenido de una manera activa y eficaz en el desenvolvimiento de nuestro arte, tanto por su labor de creador, que en los últimos tiempos ha superado un forzoso y lamentable compás de espera, como por su actuación en la Liga de Composi tores de la Argentina. Varias de sus producciones más significativas han sido interpretadas entre nosotros, como Tres ciudades, la Se gunda sonata concertata a quattro, y algunos fragmentos de su ballet Juerga, dados a conocer en 1943, en un concierto sinfónico dirigido por Juan José Casuo en el teatro Colón. Como señalé en un tra bajo aparecido en aquella fecha, que ahora reproduzco convenien temente ampliado, este estreno podría servir muy bien como pre texto-si la bondad de su música no lo justificase ya plenamente de por sí-para intentar un breve estudio sobre la personalidad artís• tica y caracteres de la obra de este talentoso compositor, estudio necesariamente incompleto, pues gran parte de su producción mu sical se perdió en los bombardeos de Madrid durante la guerra civil española-en que fué destruí da su casa. De manera que, para va rias de sus composiciones importan tes, me limitaré a reproducir las opiniones, bien autorizadas, por cierto, de un tercero-en este caso Rodolfo Halffter, quien le consagró un excelente artículo apa recido en la revista Música, de Barcelona, en Enero de 1938. -

Propuesta De Comunicación Para La Mesa

Joaquín Piñeiro / La recuperación de los compositores de la “Generación de la República” 197 La recuperación de los compositores de la “Generación de la República” durante la Transición en España The recovery of the composers of the " Generation of the Republic " during the Transition in Spain JOAQUÍN PIÑEIRO BLANCA Universidad de Cádiz (España) [email protected] Recibido: 18 de noviembre de 2017 Aceptado: 30 de diciembre de 2017 Resumen: El objetivo de este trabajo es el de analizar el modo en el que, durante el proceso de Transición en España, en el paso de la dictadura de Francisco Franco a la monarquía de Juan Carlos I, se desarrolló la recuperación de la obra de los compositores represaliados o exiliados por el franquismo como modo de fomentar la idea de cambio y la sensación de una vuelta a la normalidad política interrumpida por el golpe militar que dio fin a la II República. La generación de creadores a los que se va a prestar atención en este artículo son Rosa García Ascot, Ernesto Halftter, Rodolfo Halffter, Julián Bautista, Salvador Bacarisse, Gustavo Pittaluga, Fernando Remacha y Juan José Mantecón. Es decir, los integrantes del Grupo de los Ocho. El análisis se ha desarrollado con el apoyo de fuentes primarias, fundamentalmente hemerográficas, que dan cuenta de la actividad cultural practicada en el período que ha centrado la atención de esta investigación y que han ofrecido pistas acerca de la creciente presencia de estos autores en conciertos, grabaciones discográficas, actos de homenaje y exposiciones. Asimismo, con la utilización de fuentes secundarias, fundamentalmente las publicaciones en las que se ha estudiado a estos compositores y que suponen el estado de la cuestión del tema objeto de estudio. -

Film Essay for "Modern Times"

Modern Times By Jeffrey Vance No human being is more responsible for cinema’s ascendance as the domi- nant form of art and entertainment in the twentieth century than Charles Chaplin. Yet, Chaplin’s importance as a historic figure is eclipsed only by his creation, the Little Tramp, who be- came an iconic figure in world cinema and culture. Chaplin translated tradi- tional theatrical forms into an emerg- ing medium and changed both cinema and culture in the process. Modern screen comedy began the moment Chaplin donned his derby hat, affixed his toothbrush moustache, and Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp character finds he has become a cog in the stepped into his impossibly large wheels of industry. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. shoes for the first time. “Modern Times” is Chaplin’s self-conscious subjects such as strikes, riots, unemployment, pov- valedictory to the pantomime of silent film he had pio- erty, and the tyranny of automation. neered and nurtured into one of the great art forms of the twentieth century. Although technically a sound The opening title to the film reads, “Modern Times: a film, very little of the soundtrack to “Modern Times” story of industry, of individual enterprise, humanity contains dialogue. The soundtrack is primarily crusading in the pursuit of happiness.” At the Electro Chaplin’s own musical score and sound effects, as Steel Corporation, the Tramp is a worker on a factory well as a performance of a song by the Tramp in gib- conveyor belt. The little fellow’s early misadventures berish. This remarkable performance marks the only at the factory include being volunteered for a feeding time the Tramp ever spoke. -

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin's Influence on American

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin’s Influence on American Animation By Nancy Beiman SLIDE 1: Joe Grant trading card of Chaplin and Mickey Mouse Charles Chaplin became an international star concurrently with the birth and development of the animated cartoon. His influence on the animation medium was immense and continues to this day. I will discuss how American character animators, past and present, have been inspired by Chaplin’s work. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (SLIDE 2) Jeffrey Vance described Chaplin as “the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics”, 1 “(SLIDE 3). Charlie Chaplin” comic strips began in 1915 and it was a short step from comic strips to animation. (SLIDE 4) One of two animated Chaplin series was produced by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan Studios in 1918-19. 2 Immediately after completing the Chaplin cartoons, (SLIDE 5) Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat who was, by 1925, the most popular animated character in America. Messmer, by his own admission, based Felix’s timing and distinctive pantomime acting on Chaplin’s. 3 But no other animators of the time followed Messmer’s lead. (SLIDE 6) Animator Shamus Culhane wrote that “Right through the transition from silent films to sound cartoons none of the producers of animation paid the slightest attention to… improvements in the quality of live action comedy. Trapped by the belief that animated cartoons should be a kind of moving comic strip, all the producers, (including Walt Disney) continued to turn out films that consisted of a loose story line that supported a group of slapstick gags which were often only vaguely related to the plot….The most astonishing thing is that Walt Disney took so long to decide to break the narrow confines of slapstick, because for several decades Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton had demonstrated the superiority of good pantomime.” 4 1 Jeffrey Vance, CHAPLIN: GENIUS OF THE CINEMA, p. -

ERNESTO HALFFTER ESCRICHE (1905-1989)1 by Nancy Lee Harper ©2005

ERNESTO HALFFTER ESCRICHE (1905-1989)1 by Nancy Lee Harper ©2005 The name of Ernesto Halffter Escriche will forever be linked to that of his mentor, Manuel de Falla (1876-1946). Born during Spain's Silver Age2, he lived an intense intellectual life during a special and privileged cultural epoch. His extraordinary creativity and innate happiness3 saw him through the unusual peaks and valleys of his life. A great musician in his own right, he, like Falla, came from a mixed heritage: his being Prussian, Catalan, and Andalusian; Falla's being Valencian, Catalan, Italian, and Guatemalan. Like Falla, he had many brothers and sisters and received his first piano lessons from his mother. And like Falla, who had suffered in his youth when his father faced financial ruin, so too did Ernesto bear the impact of financial hardship imposed by his own father's misfortune. Falla and Halffter were both conductors and fine pianists. For both, contact with eminent composers in Paris had a decisive impact on their musical development and careers. Both left Spain for foreign lands because of the Spanish Civil War.4 Eventually, they both would return – Falla to be interred in the Cádiz Cathedral and Halffter to continue his own work and the legacy of Falla. Here the similarities end. Fiery Sagittarius, Falla was born in the southwest coastal city of Cádiz, while Ernesto, the earthy Capricorn, was born in mountainous Madrid. Falla, because of his ethical scruples, had to struggle with the perfection of each composition. Halffter was a natural, spontaneous talent who was enormously prolific as a composer. -

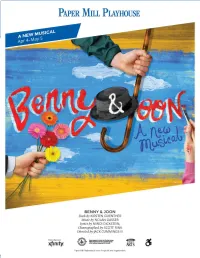

2019-BENNY-AND-JOON.Pdf

CREATIVE TEAM KIRSTEN GUENTHER (Book) is the recipient of a Richard Rodgers Award, Rockefeller Grant, Dramatists Guild Fellowship, and a Lincoln Center Honorarium. Current projects include Universal’s Heart and Souls, Measure of Success (Amanda Lipitz Productions), Mrs. Sharp (Richard Rodgers Award workshop; Playwrights Horizons, starring Jane Krakowski, dir. Michael Greif), and writing a new book to Paramount’s Roman Holiday. She wrote the book and lyrics for Little Miss Fix-it (as seen on NBC), among others. Previously, Kirsten lived in Paris, where she worked as a Paris correspondent (usatoday.com). MFA, NYU Graduate Musical Theatre Writing Program. ASCAP and Dramatists Guild. For my brother, Travis. NOLAN GASSER (Music) is a critically acclaimed composer, pianist, and musicologist—notably, the architect of Pandora Radio’s Music Genome Project. He holds a PhD in Musicology from Stanford University. His original compositions have been performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, among others. Theatrical projects include the musicals Benny & Joon and Start Me Up and the opera The Secret Garden. His book, Why You Like It: The Science and Culture of Musical Taste (Macmillan), will be released on April 30, 2019, followed by his rock/world CD Border Crossing in June 2019. His TEDx Talk, “Empowering Your Musical Taste,” is available on YouTube. MINDI DICKSTEIN (Lyrics) wrote the lyrics for the Broadway musical Little Women (MTI; Ghostlight/Sh-k-boom). Benny & Joon, based on the MGM film, was a NAMT selection (2016) and had its world premiere at The Old Globe (2017). Mindi’s work has been commissioned, produced, and developed widely, including by Disney (Toy Story: The Musical), Second Stage (Snow in August), Playwrights Horizons (Steinberg Commission), ASCAP Workshop, and Lincoln Center (“Hear and Now: Contemporary Lyricists”). -

Charlie Chaplin: the Genius Behind Comedy Zuzanna Mierzejewska College of Dupage

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by [email protected]. ESSAI Volume 9 Article 28 4-1-2011 Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy Zuzanna Mierzejewska College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Mierzejewska, Zuzanna (2011) "Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy," ESSAI: Vol. 9, Article 28. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol9/iss1/28 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mierzejewska: Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy by Zuzanna Mierzejewska (English 1102) he quote, “A picture with a smile-and perhaps, a tear” (“The Kid”) is not just an introduction to Charlie Chaplin’s silent film, The Kid, but also a description of his life in a nutshell. Many Tmay not know that despite Chaplin’s success in film and comedy, he had a very rough childhood that truly affected his adult life. Unfortunately, the audience only saw the man on the screen known world-wide as the Tramp, characterized by: his clown shoes, cane, top hat and a mustache. His humor was universal; it focused on the simplicity of our daily routines and the funniness within them. His comedy was well-appreciated during the silent film era and cheered soldiers up as they longed for peace and safety during World War I and other events in history. -

Pianista Y Compositora

LO QUE LA HISTORIA NO VE. RECONSIDERANDO LA FIGURA DE GARCÍA ASCOT Rosa García Ascot (1902-2002), pianista y compositora, fue la única mujer del conocido como Grupo de los Ocho presentado en Madrid en diciembre de 1930 e integrado, además de por ella, por Juan José Mantecón (1895-1964), Salvador Bacarisse (1898- 1963), Fernando Remacha (1898-1984), Rodolfo Halffter (1900-1987), Julián Bautista (1901-1961), Ernesto Halffter (1905-1989) y Gustavo Pittaluga (1906-1975). Surgido, por tanto, en el período de entre guerras, este grupo comparte espíritu vanguardista y planteamientos estéticos con Les Six franceses, por lo que la asociación entre ellos es inevitable. De hecho, algunos autores sugieren que la integración de una mujer en el el Grupo de los Ocho, incluso la formación del grupo mismo, podría estar relacionada con el conocimiento, por parte de los integrantes de este, de Les Six, dos de cuyos miembros (Milhaud y Poulenc) habían impartido sendas conferencias sobre la música francesa en la Residencia de Estudiantes de Madrid poco antes de que, en ese mismo espacio, se constituyeran Los Ocho. De hecho, dichas conferencias, según Palacios, habrían sido decisivas para que estos últimos se presentaran como grupo en 1930, o al menos, y muy probablemente, habrían ayudado «a definir la propia naturaleza del grupo» (Palacios, 2010b, pp. 347-348). Dentro del Grupo de los Ocho, la figura de Rosa García Ascot ha sido, en comparación con las del resto de sus integrantes, poco tratada y a menudo reducida a breves o brevísimas reseñas que se limitan a justificar su escaso protagonismo en base a una igualmente escasa obra. -

Film Essay for The

The Kid By Jeffrey Vance “The Kid” (1921) is one of Charles Chaplin’s finest achievements and remains universally beloved by critics and audiences alike. The film is a perfect blend of comedy and drama and is arguably Chap- lin’s most personal and autobiographical work. Many of the settings and the themes in the film come right out of Chaplin’s own impoverished London child- hood. However, it was the combination of two events, one tragic (the death of his infant son) and one joyful (his chance meeting with Jackie Coogan), that led Chaplin to shape the tale of the abandoned child and the lonely Tramp. The loss of three-day-old Norman Spencer Chaplin undoubtedly had a great effect on Chaplin, and the emotional pain appears to have triggered his creativ- ity, as he began auditioning child actors at the Chap- lin Studios ten days after his son’s death. It was dur- ing this period that Chaplin encountered a four-year- old child performer named Jackie Coogan at Orphe- um Theater in Los Angeles, where his father had just performed an eccentric dance act. Chaplin spent more than an hour talking to Jackie in the lob- by of the Alexandria Hotel, but the idea of using Jackie in a film did not occur to him. After he heard that Roscoe Arbuckle had just signed Coogan, Chaplin agonized over his missed opportunity. Later, Charlie Chaplin as The Tramp sits in a doorway with the he discovered that Arbuckle had signed Jack orphan he has taken under his wing (Jackie Coogan).