Charlie Chaplin in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: Reflexive Ambiguity in Modern Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letting the Other In, Queering the Nation

Letting the Other in, Queering the Nation: Bollywood and the Mimicking Body Ronie Parciack Tel Aviv University Bombay’s film industry, Bollywood, is an arena that is represented and generated by the medium as a male intensively transmits cultural products from one na - homosexual body. tionality to another; it is a mimicking arena that in - cessantly appropriates narratives of Western Culture, particularly from Hollywood. Hence its nick-name Bollywood and the work of mimicry that contains the transcultural move back and forth Bollywood, Mumbai’s cinematic industry, is an inten - between and Bombay/Mumbai, all the while retain - sive arena absorbing foreign cultural products, mainly ing the ambivalent space positioned betwixt and be - Western. Characters, cultural icons, genres, lifestyle tween, and the unsteady cultural boundaries derived accoutrements such as clothing, furnishing, recreation from the postcolonial situation. styles, western pop songs and entire cinematic texts This paper examines the manner in which this have constantly been appropriated and adapted dur - transcultural move takes place within the discourse of ing decades of film-making. gender; namely, how the mimicking strategy forms a The mimicry phenomenon, with its central locus body and provides it with an ambiguous sexual iden - in the colonial situation and the meanings it contin - tity. My discussion focuses on the film Yaraana ues to incorporate in the postcolonial context, is a (David Dhawan, 1995) – a Bollywood adaptation of loaded focus in current discourse on globalization and Sleeping with the Enemy (Joseph Ruben, 1989). The localization, homogenization and heterogenization. Hollywood story of a woman who flees a violent hus - This paper examines the way in which the mimicking band exists in the Bollywood version, but takes on a deed can highlight the gendered layout of the mim - minor role compared to its narrative focus: an (insin - icking arena. -

Film Essay for "Modern Times"

Modern Times By Jeffrey Vance No human being is more responsible for cinema’s ascendance as the domi- nant form of art and entertainment in the twentieth century than Charles Chaplin. Yet, Chaplin’s importance as a historic figure is eclipsed only by his creation, the Little Tramp, who be- came an iconic figure in world cinema and culture. Chaplin translated tradi- tional theatrical forms into an emerg- ing medium and changed both cinema and culture in the process. Modern screen comedy began the moment Chaplin donned his derby hat, affixed his toothbrush moustache, and Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp character finds he has become a cog in the stepped into his impossibly large wheels of industry. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. shoes for the first time. “Modern Times” is Chaplin’s self-conscious subjects such as strikes, riots, unemployment, pov- valedictory to the pantomime of silent film he had pio- erty, and the tyranny of automation. neered and nurtured into one of the great art forms of the twentieth century. Although technically a sound The opening title to the film reads, “Modern Times: a film, very little of the soundtrack to “Modern Times” story of industry, of individual enterprise, humanity contains dialogue. The soundtrack is primarily crusading in the pursuit of happiness.” At the Electro Chaplin’s own musical score and sound effects, as Steel Corporation, the Tramp is a worker on a factory well as a performance of a song by the Tramp in gib- conveyor belt. The little fellow’s early misadventures berish. This remarkable performance marks the only at the factory include being volunteered for a feeding time the Tramp ever spoke. -

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin's Influence on American

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin’s Influence on American Animation By Nancy Beiman SLIDE 1: Joe Grant trading card of Chaplin and Mickey Mouse Charles Chaplin became an international star concurrently with the birth and development of the animated cartoon. His influence on the animation medium was immense and continues to this day. I will discuss how American character animators, past and present, have been inspired by Chaplin’s work. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (SLIDE 2) Jeffrey Vance described Chaplin as “the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics”, 1 “(SLIDE 3). Charlie Chaplin” comic strips began in 1915 and it was a short step from comic strips to animation. (SLIDE 4) One of two animated Chaplin series was produced by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan Studios in 1918-19. 2 Immediately after completing the Chaplin cartoons, (SLIDE 5) Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat who was, by 1925, the most popular animated character in America. Messmer, by his own admission, based Felix’s timing and distinctive pantomime acting on Chaplin’s. 3 But no other animators of the time followed Messmer’s lead. (SLIDE 6) Animator Shamus Culhane wrote that “Right through the transition from silent films to sound cartoons none of the producers of animation paid the slightest attention to… improvements in the quality of live action comedy. Trapped by the belief that animated cartoons should be a kind of moving comic strip, all the producers, (including Walt Disney) continued to turn out films that consisted of a loose story line that supported a group of slapstick gags which were often only vaguely related to the plot….The most astonishing thing is that Walt Disney took so long to decide to break the narrow confines of slapstick, because for several decades Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton had demonstrated the superiority of good pantomime.” 4 1 Jeffrey Vance, CHAPLIN: GENIUS OF THE CINEMA, p. -

Glenn Mitchell the TRUE FAREWELL of the TRAMP

Glenn Mitchell THE TRUE FAREWELL OF THE TRAMP Good afternoon. I’d like to begin with an ending ... which we might call `the Tramp’s First Farewell’. CLIP: FINAL SCENE OF `THE TRAMP’ That, of course, was the finale to Chaplin’s 1915 short film THE TRAMP. Among Chaplin scholars – and I think there may be one or two here today! - one of the topics that often divides opinion is that concerning the first and last appearances of Chaplin’s Tramp character. It seems fair to suggest that Chaplin’s assembly of the costume for MABEL’S STRANGE PREDICAMENT marks his first appearance, even though he has money to dispose of and is therefore technically not a tramp. KID AUTO RACES AT VENICE, shot during its production, narrowly beat the film into release. Altogether more difficult is to pinpoint where Chaplin’s Tramp character appears for the last time. For many years, the general view was that the Tramp made his farewell at the end of MODERN TIMES. As everyone here will know, it was a revision of that famous conclusion to THE TRAMP, which we saw just now ... only this time he walks into the distance not alone, but with a female companion, one who’s as resourceful, and almost as resilient, as he is. CLIP: END OF `MODERN TIMES’ When I was a young collector starting out, one of the key studies of Chaplin’s work was The Films of Charlie Chaplin, published in 1965. Its authors, Gerald D. McDonald, Michael Conway and Mark Ricci said this of the end of MODERN TIMES: - No one realized it at the time, but in that moment of hopefulness we were seeing Charlie the Little Tramp for the last time. -

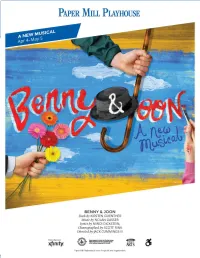

2019-BENNY-AND-JOON.Pdf

CREATIVE TEAM KIRSTEN GUENTHER (Book) is the recipient of a Richard Rodgers Award, Rockefeller Grant, Dramatists Guild Fellowship, and a Lincoln Center Honorarium. Current projects include Universal’s Heart and Souls, Measure of Success (Amanda Lipitz Productions), Mrs. Sharp (Richard Rodgers Award workshop; Playwrights Horizons, starring Jane Krakowski, dir. Michael Greif), and writing a new book to Paramount’s Roman Holiday. She wrote the book and lyrics for Little Miss Fix-it (as seen on NBC), among others. Previously, Kirsten lived in Paris, where she worked as a Paris correspondent (usatoday.com). MFA, NYU Graduate Musical Theatre Writing Program. ASCAP and Dramatists Guild. For my brother, Travis. NOLAN GASSER (Music) is a critically acclaimed composer, pianist, and musicologist—notably, the architect of Pandora Radio’s Music Genome Project. He holds a PhD in Musicology from Stanford University. His original compositions have been performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, among others. Theatrical projects include the musicals Benny & Joon and Start Me Up and the opera The Secret Garden. His book, Why You Like It: The Science and Culture of Musical Taste (Macmillan), will be released on April 30, 2019, followed by his rock/world CD Border Crossing in June 2019. His TEDx Talk, “Empowering Your Musical Taste,” is available on YouTube. MINDI DICKSTEIN (Lyrics) wrote the lyrics for the Broadway musical Little Women (MTI; Ghostlight/Sh-k-boom). Benny & Joon, based on the MGM film, was a NAMT selection (2016) and had its world premiere at The Old Globe (2017). Mindi’s work has been commissioned, produced, and developed widely, including by Disney (Toy Story: The Musical), Second Stage (Snow in August), Playwrights Horizons (Steinberg Commission), ASCAP Workshop, and Lincoln Center (“Hear and Now: Contemporary Lyricists”). -

1 Slapstick After Fordism: WALL-E, Automatism and Pixar's Fun Factory Animation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository Slapstick After Fordism: WALL-E, Automatism and Pixar’s Fun Factory animation: an interdisciplinary journal 11:1 (March 2016) Paul Flaig, University of Aberdeen In his recent The World Beyond Your Head, Matthew Crawford (2015) argues for a reclaiming of the real against the solipsism of contemporary, technologically cocooned life. Opposing digitally induced distraction, he insists on confronting the contingencies of an obstinately material, non- human world, one that rudely insists beyond our representational schema and cognitive certainties. In this Crawford joins an increasingly vocal chorus of critics questioning the ongoing transformation of human subjectivity via digital mediation and online connectivity (see Turkle 2012 and Carr 2011). Yet to mount this critique Crawford turns to a surprising example: Mickey Mouse Clubhouse, the Disney Channel’s first entirely computer animated television series, running from 2006 to the present. Given the proclaimed philosophical stakes of his book, which draws on Heidegger’s concept of “Being-in-the-World” and critiques Kantian Aufklärung, what peeks Crawford’s interest in Mickey Mouse Clubhouse, aimed at teaching pre-schoolers rudimentary concepts, facts and vocabulary? Specifically, it is the contrast between Clubhouse and Mickey’s first adventures in Disney shorts of the twenties and thirties. In the latter, “the most prominent source of hilarity is the capacity of material stuff to generate frustration,” thus offering to its viewers “a rich phenomenology of what it is like to be an embodied agent in a world of artifacts and inexorable physical laws” (70). -

Charlie Chaplin: the Genius Behind Comedy Zuzanna Mierzejewska College of Dupage

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by [email protected]. ESSAI Volume 9 Article 28 4-1-2011 Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy Zuzanna Mierzejewska College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Mierzejewska, Zuzanna (2011) "Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy," ESSAI: Vol. 9, Article 28. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol9/iss1/28 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mierzejewska: Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy by Zuzanna Mierzejewska (English 1102) he quote, “A picture with a smile-and perhaps, a tear” (“The Kid”) is not just an introduction to Charlie Chaplin’s silent film, The Kid, but also a description of his life in a nutshell. Many Tmay not know that despite Chaplin’s success in film and comedy, he had a very rough childhood that truly affected his adult life. Unfortunately, the audience only saw the man on the screen known world-wide as the Tramp, characterized by: his clown shoes, cane, top hat and a mustache. His humor was universal; it focused on the simplicity of our daily routines and the funniness within them. His comedy was well-appreciated during the silent film era and cheered soldiers up as they longed for peace and safety during World War I and other events in history. -

Film Essay for The

The Kid By Jeffrey Vance “The Kid” (1921) is one of Charles Chaplin’s finest achievements and remains universally beloved by critics and audiences alike. The film is a perfect blend of comedy and drama and is arguably Chap- lin’s most personal and autobiographical work. Many of the settings and the themes in the film come right out of Chaplin’s own impoverished London child- hood. However, it was the combination of two events, one tragic (the death of his infant son) and one joyful (his chance meeting with Jackie Coogan), that led Chaplin to shape the tale of the abandoned child and the lonely Tramp. The loss of three-day-old Norman Spencer Chaplin undoubtedly had a great effect on Chaplin, and the emotional pain appears to have triggered his creativ- ity, as he began auditioning child actors at the Chap- lin Studios ten days after his son’s death. It was dur- ing this period that Chaplin encountered a four-year- old child performer named Jackie Coogan at Orphe- um Theater in Los Angeles, where his father had just performed an eccentric dance act. Chaplin spent more than an hour talking to Jackie in the lob- by of the Alexandria Hotel, but the idea of using Jackie in a film did not occur to him. After he heard that Roscoe Arbuckle had just signed Coogan, Chaplin agonized over his missed opportunity. Later, Charlie Chaplin as The Tramp sits in a doorway with the he discovered that Arbuckle had signed Jack orphan he has taken under his wing (Jackie Coogan). -

Charlie Chaplin & Buster Keaton

SCIO. Revista de Filosofía, n.º 13, Noviembre de 2017, 77-96, ISSN: 1887-9853 CHARLIE CHAPLIN & BUSTER KEATON COMIC ANTIHERO EXTREMES DURING THE 1920S CHARLIE CHAPLIN Y BUSTER KEATON LOS DOS EXTREMOS DEL ANTIHÉROE CÓMICO DURANTE LOS AÑOS VEINTE Wes Gehringa Fechas de recepción y aceptación: 3 de abril de 2017, 13 de septiembre de 2017 In pantomime, strolling players use incomprehensible lan- guage... not for what it means but for the sake of life. [writer, actor, director Leon] Chancerel is quite right to insist upon the importance of mime. The body in the theatre... (Camus, 1962, p. 199). Abstract: The essay is a revisionist look at James Agee’s famous article “Comedy’s Greatest Era” –keying on Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin– ‘the comedy auteurs’ of the 1920s. However, while Chaplin was the giant of the era, period literature showcases that Keaton was a popular but more cult-like figure. (See my forthcoming book: Buster Keaton in his own time, McFarland Press). However, Keaton is now considered on a par with Chaplin. While the inspired comedy of Chaplin will be forever timeless, Keaton now seems to speak to today. At least a Wes D. Gehring is Ball State University’s “Distinguished Professor of Film”, Muncie, Indiana, USA. He is also the Associate Media Editor of USA TODAY Magazine for which he also writes the col- umn “Reel World”. He is the author of 36 books, including award-winning biographies of James Dean, Steve McQueen, Robert Wise, Red Skelton, and Charlie Chaplin. Correspondence: 3754 North Lakeside Drive, Muncie. Indiana 47304, United Sate of America. -

We're All Familiar with Charlie Chaplin, One of the Towering Icons

We’re all familiar with Charlie Chaplin, one of the towering icons of film history, central to the field of film as a producer, director, and actor, instantly recognizable to people around the world for his signature character The Tramp. In 1999 the American Film Institute placed him on its list of the greatest male movie stars of all time (at No.10, if you care about that sort of ranking), and it also acknowledged his film City Lights as one the 100 best American films ever made (at No. 76, just beating out his Modern Times at No. 81). Chaplin’s musical inclinations went back to his earliest years, and as a young man he achieved competence as both a singer and an instrumentalist. In My Autobiography (Simon and Schuster, 1964) he wrote of the vaudeville tour with the Karno Company that first brought him to the United States in 1910. (That troupe also included among its members another young Englishman who was Chaplin’s roommate — Arthur Stanley Jefferson, who later altered his name to Stan Laurel.) Chaplin recalled: “On this tour I carried my violin and my cello. Since the age of sixteen I had practiced from four to six hours a day in my bedroom. Each week I took lessons from the theatre conductor or from someone he recommended. As I played left-handed, my violin was strung left- handed with the bass bar and sounding post reversed. I had great ambitions to be a concert artist, or, failing that, to use it in a vaudeville act, but as time went on I realized that I could never achieve excellence, so I gave it up.” After working his way through mostly forgettable silent films, in 1919 Chaplin co-founded (along with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and D.W. -

MUSÉE CHAPLIN PÔLE CULTUREL À CORSIER-SUR-VEVEY - VD Ouvrage 2504

Version online sur la plateforme www.architectes.ch MUSÉE CHAPLIN PÔLE CULTUREL À CORSIER-SUR-VEVEY - VD ouvrage 2504 Maître de l’ouvrage Domaine du Manoir de Ban SA Rue du Collège 26 1815 Clarens Entreprise totale HRS Real Estate SA Rue du Centre 172 1025 Saint-Sulpice Architectes Itten + Brechbühl SA Avenue d’Ouchy 4 1006 Lausanne Ingénieurs civils TBM Ingénieurs SA Rue du Simplon 42 1800 Vevey Bureaux techniques CVSE : Amstein + Walthert Lausanne SA Avenue d’Ouchy 52 1006 Lausanne Physique du bâtiment Acousticien : Amstein + Walthert Lausanne SA Avenue d’Ouchy 52 1006 Lausanne Géotechnique : Bureau d’ingénieurs et de géologues Tissières SA Rue des Près-de-la-Scie 2 HISTORIQUE / SITUATION 1920 Martigny Le Manoir de Ban. Jusqu’au 25 décembre 1977, le Manoir En 2000, l’architecte suisse Philippe Meylan et le muséo- Ingénieur Sécurité : de Ban, à Corsier-sur-Vevey, était le lieu de l’intimité de graphe québécois Yves Durand conçoivent l’idée de trans- Ignis Salutem SA Chemin des Aveneyres 26 Charlie Chaplin, puis, jusqu’en 2008, de sa famille. C’est là former le Manoir de Ban en un musée qui présente l’œuvre 1806 St-Légier-La Chiésaz que l’artiste a vécu ses “années bonheur”, écrit plusieurs gigantesque d’un artiste prolifique. Quinze années pour scénarios et rédigé ses mémoires. Transformer l’endroit en affiner l’idée et obtenir, par la concertation, toutes les auto- Etude d’éclairage : Reflexion AG un site public qui rende hommage au créateur, au réalisateur risations nécessaires à sa réalisation. Du temps aussi pour Hardturmstrasse 123 et au comédien génial n’était pas chose facile. -

The Waiting Game Teacher Resource Pack

The Waiting Game Teacher Resource Pack INTRODUCTION Jesting and clowning is a very ancient art that can be traced through medieval Europe to the ancient world. Egyptian hieroglyphs, dating back to Egypt’s 5th Dynasty about 2500 BCE, depict jesters and jugglers. The fool and juggler often appear within various tarot cards that first surfaced and attracted attention in Europe at the time of the Renaissance. The Fool is always depicted within the cards of the tarot and carries special meanings. Ultimately it symbolizes a new start. A chance to live in the present moment and transcend the unfortunate aspects of ones past that if re-lived would be sure to bring about the same results. The fool represents the infinite possibility within human development or the negation of those possibilities by the ego. It represents the spirit of adventure ever ready to leave safe places and conformity in order to discover new opportunity. For many modern audiences, clowns represent our inner child. They are possessed of a childlike innocence and wonder of the world about them, a playfulness and an irreverence, and the freedom of not following the rules that apply to the rest of us. Ask a clown to do a perfectly normal task and mayhem will ensue. Like the act of waiting… These notes are designed to give you a concise resource to use with your class and to support their experience of seeing The Waiting Game. CLASSROOM CONTENT AND CURRICULUM LINKS Essential Learnings: The Arts (Drama), SOSE (History) and English Style/Form: Traditional & Contemporary Clowning, Melodrama, Visual Theatre, Physical Comedy, Physical Theatre, Non-verbal Communication 7 Mime, Improvisation, Slapstick Themes and Contexts: Creativity, Imagination, Transformation, Play, Audience Engagement and Interaction, Roles 7 Relationships, Status, Choices and Dramatic Form.