We're All Familiar with Charlie Chaplin, One of the Towering Icons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Events Brochure

1 THE EXCLUSIVE WORLD OF CHAPLIN FOR YOUR EVENTS 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENT 5 12 26 Chaplin is back Backstage Easy Street & The Circus 6 14 28 Infinite possibilities The Manoir: A space rich with emotion Hollywood Boulevard 9 22 30 A site covering 4 hectares Le Studio Restaurant: The Tramp 10 24 35 Welcome to Chaplin’s World ! The Cinema Practical information 36 Contact 4 5 CHAPLIN’S CHAPLIN WORLD IS BACK CHAPLIN’S WORLD ABSOLUTELY UNIQUE Immerse yourself in the universe of Charlie Chaplin and experience the emotion of encountering one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. harlie Chaplin is a legend, known and entertaining museum designed to plunge you Cloved all over the planet. His positive aura into the private and Hollywood life of Charlie continues to shine on the world – the very Chaplin, allowing you to discover both the man world he portrayed through his comic and and the artist: Charlie and the Tramp. Play human vision. The Tramp, his iconic character, among sets from his movies and make one of has brought, and continues to bring laughter the most beautiful spots in the Riviera your own to millions of people. Situated between lake private paradise. and mountain, Chaplin’s World By Grévin is an 6 7 INFINITE POSSIBILITIES haplin’s World By Grévin offers the PRESTIGIOUS SPACES AT THE HEART OF Crental of the entire site or certain A UNIQUE CULTURAL DESTINATION FOR: areas for the organization of private receptions, events, and activities for PROFESSIONAL EVENTS INCLUDING individuals and companies. These events Presentations and assemblies can be paired with museum visits. -

Film Essay for "Modern Times"

Modern Times By Jeffrey Vance No human being is more responsible for cinema’s ascendance as the domi- nant form of art and entertainment in the twentieth century than Charles Chaplin. Yet, Chaplin’s importance as a historic figure is eclipsed only by his creation, the Little Tramp, who be- came an iconic figure in world cinema and culture. Chaplin translated tradi- tional theatrical forms into an emerg- ing medium and changed both cinema and culture in the process. Modern screen comedy began the moment Chaplin donned his derby hat, affixed his toothbrush moustache, and Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp character finds he has become a cog in the stepped into his impossibly large wheels of industry. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. shoes for the first time. “Modern Times” is Chaplin’s self-conscious subjects such as strikes, riots, unemployment, pov- valedictory to the pantomime of silent film he had pio- erty, and the tyranny of automation. neered and nurtured into one of the great art forms of the twentieth century. Although technically a sound The opening title to the film reads, “Modern Times: a film, very little of the soundtrack to “Modern Times” story of industry, of individual enterprise, humanity contains dialogue. The soundtrack is primarily crusading in the pursuit of happiness.” At the Electro Chaplin’s own musical score and sound effects, as Steel Corporation, the Tramp is a worker on a factory well as a performance of a song by the Tramp in gib- conveyor belt. The little fellow’s early misadventures berish. This remarkable performance marks the only at the factory include being volunteered for a feeding time the Tramp ever spoke. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin's Influence on American

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin’s Influence on American Animation By Nancy Beiman SLIDE 1: Joe Grant trading card of Chaplin and Mickey Mouse Charles Chaplin became an international star concurrently with the birth and development of the animated cartoon. His influence on the animation medium was immense and continues to this day. I will discuss how American character animators, past and present, have been inspired by Chaplin’s work. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (SLIDE 2) Jeffrey Vance described Chaplin as “the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics”, 1 “(SLIDE 3). Charlie Chaplin” comic strips began in 1915 and it was a short step from comic strips to animation. (SLIDE 4) One of two animated Chaplin series was produced by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan Studios in 1918-19. 2 Immediately after completing the Chaplin cartoons, (SLIDE 5) Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat who was, by 1925, the most popular animated character in America. Messmer, by his own admission, based Felix’s timing and distinctive pantomime acting on Chaplin’s. 3 But no other animators of the time followed Messmer’s lead. (SLIDE 6) Animator Shamus Culhane wrote that “Right through the transition from silent films to sound cartoons none of the producers of animation paid the slightest attention to… improvements in the quality of live action comedy. Trapped by the belief that animated cartoons should be a kind of moving comic strip, all the producers, (including Walt Disney) continued to turn out films that consisted of a loose story line that supported a group of slapstick gags which were often only vaguely related to the plot….The most astonishing thing is that Walt Disney took so long to decide to break the narrow confines of slapstick, because for several decades Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton had demonstrated the superiority of good pantomime.” 4 1 Jeffrey Vance, CHAPLIN: GENIUS OF THE CINEMA, p. -

Glenn Mitchell the TRUE FAREWELL of the TRAMP

Glenn Mitchell THE TRUE FAREWELL OF THE TRAMP Good afternoon. I’d like to begin with an ending ... which we might call `the Tramp’s First Farewell’. CLIP: FINAL SCENE OF `THE TRAMP’ That, of course, was the finale to Chaplin’s 1915 short film THE TRAMP. Among Chaplin scholars – and I think there may be one or two here today! - one of the topics that often divides opinion is that concerning the first and last appearances of Chaplin’s Tramp character. It seems fair to suggest that Chaplin’s assembly of the costume for MABEL’S STRANGE PREDICAMENT marks his first appearance, even though he has money to dispose of and is therefore technically not a tramp. KID AUTO RACES AT VENICE, shot during its production, narrowly beat the film into release. Altogether more difficult is to pinpoint where Chaplin’s Tramp character appears for the last time. For many years, the general view was that the Tramp made his farewell at the end of MODERN TIMES. As everyone here will know, it was a revision of that famous conclusion to THE TRAMP, which we saw just now ... only this time he walks into the distance not alone, but with a female companion, one who’s as resourceful, and almost as resilient, as he is. CLIP: END OF `MODERN TIMES’ When I was a young collector starting out, one of the key studies of Chaplin’s work was The Films of Charlie Chaplin, published in 1965. Its authors, Gerald D. McDonald, Michael Conway and Mark Ricci said this of the end of MODERN TIMES: - No one realized it at the time, but in that moment of hopefulness we were seeing Charlie the Little Tramp for the last time. -

Lecture Outlines

21L011 The Film Experience Professor David Thorburn Lecture 1 - Introduction I. What is Film? Chemistry Novelty Manufactured object Social formation II. Think Away iPods The novelty of movement Early films and early audiences III. The Fred Ott Principle IV. Three Phases of Media Evolution Imitation Technical Advance Maturity V. "And there was Charlie" - Film as a cultural form Reference: James Agee, A Death in the Family (1957) Lecture 2 - Keaton I. The Fred Ott Principle, continued The myth of technological determinism A paradox: capitalism and the movies II. The Great Train Robbery (1903) III. The Lonedale Operator (1911) Reference: Tom Gunning, "Systematizing the Electronic Message: Narrative Form, Gender and Modernity in 'The Lonedale Operator'." In American Cinema's Transitional Era, ed. Charlie Keil and Shelley Stamp. Univ. of California Press, 1994, pp. 15-50. IV. Buster Keaton Acrobat / actor Technician / director Metaphysician / artist V. The multiplicity principle: entertainment vs. art VI. The General (1927) "A culminating text" Structure The Keaton hero: steadfast, muddling The Keaton universe: contingency Lecture 3 - Chaplin 1 I. Movies before Chaplin II. Enter Chaplin III. Chaplin's career The multiplicity principle, continued IV. The Tramp as myth V. Chaplin's world - elemental themes Lecture 4 - Chaplin 2 I. Keaton vs. Chaplin II. Three passages Cops (1922) The Gold Rush (1925) City Lights (1931) III. Modern Times (1936) Context A culminating film The gamin Sound Structure Chaplin's complexity Lecture 5 - Film as a global and cultural form I. Film as a cultural form Global vs. national cinema American vs. European cinema High culture vs. Hollywood II. -

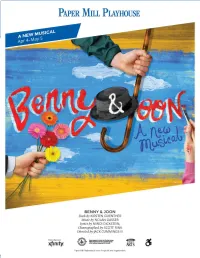

2019-BENNY-AND-JOON.Pdf

CREATIVE TEAM KIRSTEN GUENTHER (Book) is the recipient of a Richard Rodgers Award, Rockefeller Grant, Dramatists Guild Fellowship, and a Lincoln Center Honorarium. Current projects include Universal’s Heart and Souls, Measure of Success (Amanda Lipitz Productions), Mrs. Sharp (Richard Rodgers Award workshop; Playwrights Horizons, starring Jane Krakowski, dir. Michael Greif), and writing a new book to Paramount’s Roman Holiday. She wrote the book and lyrics for Little Miss Fix-it (as seen on NBC), among others. Previously, Kirsten lived in Paris, where she worked as a Paris correspondent (usatoday.com). MFA, NYU Graduate Musical Theatre Writing Program. ASCAP and Dramatists Guild. For my brother, Travis. NOLAN GASSER (Music) is a critically acclaimed composer, pianist, and musicologist—notably, the architect of Pandora Radio’s Music Genome Project. He holds a PhD in Musicology from Stanford University. His original compositions have been performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, among others. Theatrical projects include the musicals Benny & Joon and Start Me Up and the opera The Secret Garden. His book, Why You Like It: The Science and Culture of Musical Taste (Macmillan), will be released on April 30, 2019, followed by his rock/world CD Border Crossing in June 2019. His TEDx Talk, “Empowering Your Musical Taste,” is available on YouTube. MINDI DICKSTEIN (Lyrics) wrote the lyrics for the Broadway musical Little Women (MTI; Ghostlight/Sh-k-boom). Benny & Joon, based on the MGM film, was a NAMT selection (2016) and had its world premiere at The Old Globe (2017). Mindi’s work has been commissioned, produced, and developed widely, including by Disney (Toy Story: The Musical), Second Stage (Snow in August), Playwrights Horizons (Steinberg Commission), ASCAP Workshop, and Lincoln Center (“Hear and Now: Contemporary Lyricists”). -

Two-Color Technicolor, the Black Pirate, and Blackened Dyes in 1923

Two-Color Technicolor, The Black Pirate, and Blackened Dyes In 1923 Cecil B. DeMille had complained that “color movies diverted interest from narrative and action, offended the color sensitivities of many, and cost too much.”1 For DeMille, color—even “natural” color processes like Technicolor—was a veil that concealed the all-important expressions on an actor’s face. Yet DeMille was attracted to color and repeatedly employed it in his films of the 1920s, combining tinting and toning with footage either in Technicolor or in the Handshiegl process. Douglas Fairbanks voiced a similar objection to color, likening its use to putting “rouge on the lips of Venus de Milo.”2 Fairbanks argued that color took “the mind of the spectator away from the picture itself, making him conscious of the mechanics—the artificiality—of the whole thing, so that he no longer lived in the story with the characters.”3 At the same time, color motion pictures were said, by their critics, to cause retinal fatigue.4 Fairbanks had once written that color “would tire and distract the eye,” serving more as a distraction than an attraction.5 Indeed, a few years later, before deciding to make The Black Pirate (1926) in two-color Technicolor, Fairbanks hired two USC professors, Drs. A. Ray Irvine and M. F. Weyman, to conduct a series of tests to ascertain the relative amount of eye fatigue (as well as nausea and headaches) generated by viewing black and white vs. color films. Fatigue was calculated in terms of the decline in the viewer’s visual acuity as a result of these screenings. -

Charlie Chaplin: the Genius Behind Comedy Zuzanna Mierzejewska College of Dupage

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by [email protected]. ESSAI Volume 9 Article 28 4-1-2011 Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy Zuzanna Mierzejewska College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Mierzejewska, Zuzanna (2011) "Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy," ESSAI: Vol. 9, Article 28. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol9/iss1/28 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mierzejewska: Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy by Zuzanna Mierzejewska (English 1102) he quote, “A picture with a smile-and perhaps, a tear” (“The Kid”) is not just an introduction to Charlie Chaplin’s silent film, The Kid, but also a description of his life in a nutshell. Many Tmay not know that despite Chaplin’s success in film and comedy, he had a very rough childhood that truly affected his adult life. Unfortunately, the audience only saw the man on the screen known world-wide as the Tramp, characterized by: his clown shoes, cane, top hat and a mustache. His humor was universal; it focused on the simplicity of our daily routines and the funniness within them. His comedy was well-appreciated during the silent film era and cheered soldiers up as they longed for peace and safety during World War I and other events in history. -

40 Years of American Film Comedy to Be Shown

40n8 - 4?' THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART tl WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK •fgLEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FORTY YEARS OF AMERICAN FIM COMEDY FROM FLORA FINCH AND JOHN BUNNY TO CHAPLIN, FIELDS, BENCHLEY AND THE MARX BROTHERS TO BE SHOWN AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART That movies are the proper study of mankind has been estab lished at the Museum of Modern Art, where eight comprehensive series and four smaller groups of the outstanding films through which the great popular art of the cinema has evolved since 1895, have already been shown to Museum visitors. The Museum now announces a new series of fifteen programs in the art of the motion picture under the general title: Forty Years of American Film Comedy, Part i; Beginning Thursday, August 1, the series will be presented dally at 4 P.M. and on Sundays at 3 P.M. and 4 P.M. in the Museum1s auditorium at 11 West 53 Street. Instruction will thus be provided from the screen by Professors Mack Sennett, Frank Capra, W. C. Fields, Harpo and Groucho Marx, Robert Benchley and Charlie Chaplin in a new appraisal of screen comedy reviewed in the light of history. "It is very evident," states Iris Barry, Curator of the Museum's Film Library, "that the great farce-comedies, as well as the cowboy and gangster films, rank among this country1s most original contributions to the screen. We are grateful indeed to the film industry for cooperating with the Museum in providing this unique opportunity for tracing screen comedy to its sources in this group of classics now restored to view for the amateurs of the twentieth century's liveliest art. -

Film Essay for The

The Kid By Jeffrey Vance “The Kid” (1921) is one of Charles Chaplin’s finest achievements and remains universally beloved by critics and audiences alike. The film is a perfect blend of comedy and drama and is arguably Chap- lin’s most personal and autobiographical work. Many of the settings and the themes in the film come right out of Chaplin’s own impoverished London child- hood. However, it was the combination of two events, one tragic (the death of his infant son) and one joyful (his chance meeting with Jackie Coogan), that led Chaplin to shape the tale of the abandoned child and the lonely Tramp. The loss of three-day-old Norman Spencer Chaplin undoubtedly had a great effect on Chaplin, and the emotional pain appears to have triggered his creativ- ity, as he began auditioning child actors at the Chap- lin Studios ten days after his son’s death. It was dur- ing this period that Chaplin encountered a four-year- old child performer named Jackie Coogan at Orphe- um Theater in Los Angeles, where his father had just performed an eccentric dance act. Chaplin spent more than an hour talking to Jackie in the lob- by of the Alexandria Hotel, but the idea of using Jackie in a film did not occur to him. After he heard that Roscoe Arbuckle had just signed Coogan, Chaplin agonized over his missed opportunity. Later, Charlie Chaplin as The Tramp sits in a doorway with the he discovered that Arbuckle had signed Jack orphan he has taken under his wing (Jackie Coogan). -

Charlie Chaplin Biography - Life, Childhood, Children, Parents, Story, History, Wife, School, Mother, Information, Born, Contract

3/5/2020 Charlie Chaplin Biography - life, childhood, children, parents, story, history, wife, school, mother, information, born, contract World Biography (../in… / Ch-Co (index.html) / Charlie Chaplin Bi… Charlie Chaplin Biography Born: April 16, 1889 London, England Died: December 25, 1977 Vevey, Switzerland English actor, director, and writer The film actor, director, and writer Charlie Chaplin was one of the most original creators in the history of movies. His performances as "the tramp"—a sympathetic comic character with ill-fitting clothes and a mustache—won admiration from audiences across the world. Rough childhood Charles Spencer Chaplin was born in a poor district of London, England, on April 16, 1889. His mother, Hannah Hill Chaplin, a talented singer, actress, and piano player, spent most of her life in and out of mental hospitals; his father, Charles Spencer Chaplin Sr. was a fairly successful singer until he began drinking. After his parents separated, Charlie and his half-brother, Sidney, spent most of their childhood in orphanages, where they often went hungry and were beaten if they misbehaved. Barely able to read and write, Chaplin left school to tour with a group of comic entertainers. Later he starred in a comedy act. By the age of nineteen he had become one of the most popular music-hall performers in England. Arrives in the United States In 1910 Chaplin went to the United States to tour in A Night in an English Music Hall. He was chosen by filmmaker Mack Sennett (1884–1960) to appear in the silent Keystone comedy series. In these early movies ( Making a Living, Tillie's Punctured Romance ), Chaplin changed his style.