Unit 9 Shang Civilization in China*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Wall of China the Great Wall of China Is 5,500Miles, 10,000 Li and Length Is 8,851.8Km

The Great Wall of China The Great Wall of China is 5,500miles, 10,000 Li and Length is 8,851.8km How they build the great wall is they use slaves,farmers,soldiers and common people. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/facts/ The Great Wall is made between 1368-1644. The Great Wall of China is not the biggest wall,but is the longest. http://community.travelchinaguide.com/photo-album/show.asp?aid=2278 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Is_the_Great_Wall_of_China_the_biggest_wall_in_the_world?#slide2 The Great Wall It said that there was million is so long that people were building the Great like a River. Wall and many of them lost their lives.There is even childrens had to be part of it. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/construction/labor_force.htm The Great Wall is so long that over Qin Shi Huang 11 provinces and 58 cities. is the one who start the Great Wall who decide to Start the Great Wall. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Wall_of_China http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_cities_does_the_great_wall_of_china_go_through#slide2 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_provinces_does_the_Great_Wall_of_China_go_through#slide2 Over Million people helped to build the Great Wall of China. The Great Wall is pretty old. http://facts.randomhistory.com/2009/04/18_great-wall.html There is more than one part of Great Wall There is five on the map of BeiJing When the Great Wall was build lots people don’t know where they need to go.Most of them lost their home and their part of Family. http://www.tour-beijing.com/great_wall/?gclid=CPeMlfXlm7sCFWJo7Aod- 3IAIA#.UqHditlkFxU The Great Wall is so long that is almost over all the states. -

GREAT WALL of CHINA Deconstructing

GREAT WALL OF CHINA Deconstructing History: Great Wall of China It took millennia to build, but today the Great Wall of China stands out as one of the world's most famous landmarks. Perhaps the most recognizable symbol of China and its long and vivid history, the Great Wall of China actually consists of numerous walls and fortifications, many running parallel to each other. Originally conceived by Emperor Qin Shi Huang (c. 259-210 B.C.) in the third century B.C. as a means of preventing incursions from barbarian nomads into the Chinese Empire, the wall is one of the most extensive construction projects ever completed… Though the Great Wall never effectively prevented invaders from entering China, it came to function more as a psychological barrier between Chinese civilization and the world, and remains a powerful symbol of the country’s enduring strength. QIN DYNASTY CONSTRUCTION Though the beginning of the Great Wall of China can be traced to the third century B.C., many of the fortifications included in the wall date from hundreds of years earlier, when China was divided into a number of individual kingdoms during the so-called Warring States Period. Around 220 B.C., Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, ordered that earlier fortifications between states be removed and a number of existing walls along the northern border be joined into a single system that would extend for more than 10,000 li (a li is about one-third of a mile) and protect China against attacks from the north. -

For the Purposes of This Chapter Is Therefore Die Second Half of the Second Millennium B.C

SHANG ARCHAEOLOGY 139 for the purposes of this chapter is therefore die second half of the second millennium B.C. Bronze artifacts define the scope of the chapter. They are also one of its principal sources of information, for in the present state of archaeological knowledge many of the societies to which they draw our attention are known only from finds of bronzes. Fortunately much can be learned from objects which in their time were plainly of high importance - second only, perhaps, to architecture, of which scant trace survives. In second-millennium China the bronzes made for ritual or mortuary purposes were products of an extremely sophisticated technology on which immense resources were lav- ished. They have an individuality that sensitively registers differences of time and place; cultural differences and interactions can be read from their types, decoration, and assemblages. Because they served political or religious func- tions for elites, they reflect the activities of the highest strata of society; unlike the pottery on which archaeology normally depends, they supply informa- tion that can be interpreted in terms somewhat resembling those of narra- tive history. Moreover the value which has attached to ancient bronzes throughout Chinese history makes them today the most systematically reported of chance finds, with the result that the geographic distribution of published bronze finds is very wide.23 No other sample of the archaeological record is equally comprehensive — no useful picture would emerge from a survey of architecture or lacquer or jade — and the study of bronzes is thus the best available corrective to the textual bias of Chinese archaeology. -

Social Complexity in North China During the Early Bronze Age: a Comparative Study of the Erlitou and Lower Xiajiadian Cultures

Social Complexity in North China during the Early Bronze Age: A Comparative Study of the Erlitou and Lower Xiajiadian Cultures GIDEON SHELACH ACCORDING TO TRADITIONAL Chinese historiography, the earliest Chinese state was the Xia dynasty (twenty-first-seventeenth centuries B.C.), which was lo cated in the Zhongyuan area (the Central Plain). The traditional viewpoint also relates that, over the next two millennia, complex societies emerged in other parts of present-day China through the process of political expansion and cul tural diffusion from the Zhongyuan. Some scholars recently have challenged this model because it is unilinear and does not allow for significant contributions to the emergence of social compleXity from areas outside the Zhongyuan. Recent syntheses usually view the archaeological landscape of the late Neolithic Period (the second half of the third millennium B.C.) as a mosaic of cultures of compar able social complexity that interacted and influenced each other (Chang 1986; Tong 1981). Nevertheless, when dealing with the Early Bronze Age, the period identified with the Xia dynasty, most archaeologists still accept the main premises of the traditional model. They regard the culture or cultures of the Zhongyuan as the most developed and see intercultural interaction as occurring, if at all, only within the boundaries of that area. One of the most heated debates among Chinese archaeologists in recent years has been over the archaeological identification of the Xia dynasty. The partici pants in this debate accept the authenticity of the historical documents, most of which were written more than a thousand years after the events, and try to cor relate names of historical places and peoples to known archaeological sites and cultures. -

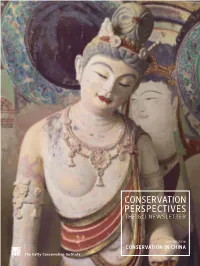

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China Democratic Revolution in China, Was Launched There

Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy The Great Wall of China In c. 220 BC, under Qin Shihuangdi (first emperor of the Qin dynasty), sections of earlier fortifications were joined together to form a united system to repel invasions from the north. Construction of the Great Wall continued for more than 16 centuries, up to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), National Emblem of China creating the world's largest defense structure. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. The design of the national emblem of the People's Republic of China shows Tiananmen under the light of five stars, and is framed with ears of grain and a cogwheel. Tiananmen is the symbol of modern China because the May 4th Movement of 1919, which marked the beginning of the new- Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China democratic revolution in China, was launched there. The meaning of the word David M. Darst, CFA Tiananmen is “Gate of Heavenly Succession.” On the emblem, the cogwheel and the ears of grain represent the working June 2011 class and the peasantry, respectively, and the five stars symbolize the solidarity of the various nationalities of China. The Han nationality makes up 92 percent of China’s total population, while the remaining eight percent are represented by over 50 nationalities, including: Mongol, Hui, Tibetan, Uygur, Miao, Yi, Zhuang, Bouyei, Korean, Manchu, Kazak, and Dai. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. Please refer to important information, disclosures, and qualifications at the end of this material. Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy Table of Contents The Chinese Dynasties Section 1 Background Page 3 Length of Period Dynasty (or period) Extent of Period (Years) Section 2 Issues for Consideration Page 65 Xia c. -

Cultic Practices of the Bronze Age Chengdu Plain

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 149 May, 2005 A Sacred Trinity: God, Mountain and Bird. Cultic Practices of the Bronze Age Chengdu Plain by Kimberley S. Te Winkle Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Of the Chinese Bronze

READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Ar chaeolo gy of the Archaeology of the Chinese Bronze Age is a synthesis of recent Chinese archaeological work on the second millennium BCE—the period Ch associated with China’s first dynasties and East Asia’s first “states.” With a inese focus on early China’s great metropolitan centers in the Central Plains Archaeology and their hinterlands, this work attempts to contextualize them within Br their wider zones of interaction from the Yangtze to the edge of the onze of the Chinese Bronze Age Mongolian steppe, and from the Yellow Sea to the Tibetan plateau and the Gansu corridor. Analyzing the complexity of early Chinese culture Ag From Erlitou to Anyang history, and the variety and development of its urban formations, e Roderick Campbell explores East Asia’s divergent developmental paths and re-examines its deep past to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of China’s Early Bronze Age. Campbell On the front cover: Zun in the shape of a water buffalo, Huadong Tomb 54 ( image courtesy of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Institute for Archaeology). MONOGRAPH 79 COTSEN INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY PRESS Roderick B. Campbell READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Archaeology of the Chinese Bronze Age From Erlitou to Anyang Roderick B. Campbell READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Monographs Contributions in Field Research and Current Issues in Archaeological Method and Theory Monograph 78 Monograph 77 Monograph 76 Visions of Tiwanaku Advances in Titicaca Basin The Dead Tell Tales Alexei Vranich and Charles Archaeology–2 María Cecilia Lozada and Stanish (eds.) Alexei Vranich and Abigail R. -

Shang Ritual and Social Dynamics at Anyang: an Analysis Of

SHANG RITUAL AND SOCIAL DYNAMICS AT ANYANG: AN ANALYSIS OF DASIKONG AND HUAYUANZHUANG EAST BURIALS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY MAY 2017 By Andrew E. MacIver Thesis Committee: Christian Peterson, Chairperson Miriam Stark Edward Davis Keywords: Shang, Quantitative Analysis, Ritual, Burial Acknowledgements I would like to thank my committee members, Christian Peterson, Miriam Stark, and Edward Davis, at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa for their support and assistance in conducting this research. In particular, I would like to gratefully acknowledge Christian Peterson for his help in designing the quantitative analysis and providing helpful input throughout. I also would like to thank Li Zhipeng and Tang Jigen for meeting with me to discuss this project. I would also like to acknowledge the help He Simeiqi has provided in graciously reviewing my work. i Abstract The Shang period (1600-1046 BC) of early China has received considerable attention in archaeology. Ritual is thought to be important in the development of Shang society. However, there are considerable gaps in knowledge pertaining to the relationship between ritual and society across the entire sociopolitical spectrum. Burials hold great potential in furthering our understanding on the formation and maintenance of the Shang belief system and the relationship between ritual and society across this spectrum. This analysis reveals the substantial -

A City with Many Faces: Urban Development in Pre-Modern China (C

A city with many faces: urban development in pre-modern China (c. 3000 BC - AD 900) WANG TAO Introduction Urbanism is an important phenomenon in human history. Comparative studies have, however, shown that each city possesses its own characteristics within a particular historical context. The fundamental elements that determine the construction and functions of a city, such as the economic, political, military and religious factors, play different roles in different cases. In other words, each city may potentially be unique. Modern scholars have now realised that the most appropriate way to approach a city is to approach it in its own cultural tradition. To understand the cultures of different cities and the idea of urbanism and its manifestations in various contexts, we must consider the experiences and feelings of the people who lived in these cities rather than just the half-buried city walls and broken roof tiles. In this chapter I will examine different models and the crucial stages of urbanisation in pre-modern China, mainly from an archaeological perspective, but also in conjunction with some contemporary historical sources. The aim is to reveal a general pattern, if there is one, and the key elements that underlay the development of Chinese cities from 3000 BC to AD 900. The ideal city and some basic terms: cheng/yi, du, guo, she, jiao, li/fang, shi A good way to detect what people think of their cities is to find out what they call them. The most common word in the Chinese language for city is cheng, meaning a walled settlement. -

Financial Institutions Step Forward to Save Businesses

6 | DISCOVER SHANXI Friday, March 20, 2020 CHINA DAILY Financial institutions step forward to save businesses The loan packages to the compa ny totaled 180 million yuan, accord ing to Shi. The procedure for applying for lending has been greatly stream lined. “It took only two days for the Shanxi branch of Agricultural Bank Increased lending of China to approve a loan of 50 mil to help companies lion yuan, after quickly examining The last patient of the novel coronavirus in Shanxi is cured and our financial situation and qualifi discharged from hospital on March 13. ZHANG BAOMING / FOR CHINA DAILY facing pressure cation,” Shi said. The Shanxi branches of the Agri By YUAN SHENGGAO cultural Development Bank of Chi na and Postal Saving Bank of China Province recovers fast Financial institutions in North Chi have shifted their focuses to serve na’s Shanxi province are taking steps local small and mediumsized enter to support local businesses in resum prises. ing operation by offering incentivized Tiantian Restaurant in Xiyang with all patients cured lending and facilitation measures, Employees at Pingyao Beef Group inspect products before they are county is an SME in Shanxi under according to local media reports. delivered to markets. LIU JIAQIONG / FOR CHINA DAILY great pressure. By YUAN SHENGGAO days, according to the Shanxi Since the outbreak of the novel With no business for more than a Health Commission. coronavirus epidemic, businesses in month, the company needed to pay The last patient of the novel The commission said all 117 Shanxi have faced difficulties due to While only half of the workers are interest rate of 3.15 percent. -

October 20, 2010 Beijing – Jinan – Qufu – Zibo – Weifang – Yantai – Qingdao – Suzhou –Shanghai

____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Sacramento-Jinan Sister-City 25th Anniversary Trip to China October 7, 2010 – October 20, 2010 Beijing – Jinan – Qufu – Zibo – Weifang – Yantai – Qingdao – Suzhou –Shanghai Tour Highlights: ¾ Attend celebration activities in Jinan for the 25th Anniversary of Sacramento-Jinan sister- city relationship as a member of the official delegation and invited guests to Jinan ¾ Climb the Great Wall of China and see giant panda bears with your own eyes ¾ Visit the World Expo in Shanghai ¾ Learn Chinese culture through tours of gardens ¾ Tour major cities in Shandong (山东), one of the most prosperous and populous provinces of China with Jinan as its capital city and Confucius as its most illustrious son: enjoy tour of Confucius’ birthplace, wine tasting, beer museum, folk arts and ceramics, etc. For more information, please contact Grace at [email protected] or Gloria at 916.685.8049. Visit us at the City of Sacramento’s website http://www.cityofsacramento.org/sistercities/jinan.htm or our homepage www.jsscc.org. Itinerary Day 1 10/07/2010 San Francisco – Beijing Fly from San Francisco to Beijing. A full meal and beverage service will be available during this overnight flight. The International Date Line will be crossed during the flight. Day 2 10/08/2010 Beijing (北京) – Capital of China Arrive in Beijing, transfer to 4-star hotel, welcome dinner (D) Day 3 10/09/2010 Beijing Visit the Great Wall, Cloisonné Factory, Summer Palace, Beijing Olympic Park. Enjoy a Peking Duck Dinner. (B-L-D) Day 4 10/10/2010 Beijing – Jinan Tour the Tian’anmen Square, Forbidden City (The Palace Museum), Beijing Zoo.