Chinese Eunuchs, in General Assessments of the Eunuch System, by Both Western and Asian Commentators, Have Been Uniformly Critical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Wall of China the Great Wall of China Is 5,500Miles, 10,000 Li and Length Is 8,851.8Km

The Great Wall of China The Great Wall of China is 5,500miles, 10,000 Li and Length is 8,851.8km How they build the great wall is they use slaves,farmers,soldiers and common people. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/facts/ The Great Wall is made between 1368-1644. The Great Wall of China is not the biggest wall,but is the longest. http://community.travelchinaguide.com/photo-album/show.asp?aid=2278 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Is_the_Great_Wall_of_China_the_biggest_wall_in_the_world?#slide2 The Great Wall It said that there was million is so long that people were building the Great like a River. Wall and many of them lost their lives.There is even childrens had to be part of it. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/construction/labor_force.htm The Great Wall is so long that over Qin Shi Huang 11 provinces and 58 cities. is the one who start the Great Wall who decide to Start the Great Wall. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Wall_of_China http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_cities_does_the_great_wall_of_china_go_through#slide2 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_provinces_does_the_Great_Wall_of_China_go_through#slide2 Over Million people helped to build the Great Wall of China. The Great Wall is pretty old. http://facts.randomhistory.com/2009/04/18_great-wall.html There is more than one part of Great Wall There is five on the map of BeiJing When the Great Wall was build lots people don’t know where they need to go.Most of them lost their home and their part of Family. http://www.tour-beijing.com/great_wall/?gclid=CPeMlfXlm7sCFWJo7Aod- 3IAIA#.UqHditlkFxU The Great Wall is so long that is almost over all the states. -

GREAT WALL of CHINA Deconstructing

GREAT WALL OF CHINA Deconstructing History: Great Wall of China It took millennia to build, but today the Great Wall of China stands out as one of the world's most famous landmarks. Perhaps the most recognizable symbol of China and its long and vivid history, the Great Wall of China actually consists of numerous walls and fortifications, many running parallel to each other. Originally conceived by Emperor Qin Shi Huang (c. 259-210 B.C.) in the third century B.C. as a means of preventing incursions from barbarian nomads into the Chinese Empire, the wall is one of the most extensive construction projects ever completed… Though the Great Wall never effectively prevented invaders from entering China, it came to function more as a psychological barrier between Chinese civilization and the world, and remains a powerful symbol of the country’s enduring strength. QIN DYNASTY CONSTRUCTION Though the beginning of the Great Wall of China can be traced to the third century B.C., many of the fortifications included in the wall date from hundreds of years earlier, when China was divided into a number of individual kingdoms during the so-called Warring States Period. Around 220 B.C., Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, ordered that earlier fortifications between states be removed and a number of existing walls along the northern border be joined into a single system that would extend for more than 10,000 li (a li is about one-third of a mile) and protect China against attacks from the north. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

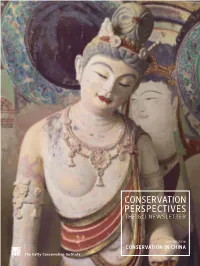

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China Democratic Revolution in China, Was Launched There

Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy The Great Wall of China In c. 220 BC, under Qin Shihuangdi (first emperor of the Qin dynasty), sections of earlier fortifications were joined together to form a united system to repel invasions from the north. Construction of the Great Wall continued for more than 16 centuries, up to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), National Emblem of China creating the world's largest defense structure. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. The design of the national emblem of the People's Republic of China shows Tiananmen under the light of five stars, and is framed with ears of grain and a cogwheel. Tiananmen is the symbol of modern China because the May 4th Movement of 1919, which marked the beginning of the new- Portfolio Investment Opportunities in China democratic revolution in China, was launched there. The meaning of the word David M. Darst, CFA Tiananmen is “Gate of Heavenly Succession.” On the emblem, the cogwheel and the ears of grain represent the working June 2011 class and the peasantry, respectively, and the five stars symbolize the solidarity of the various nationalities of China. The Han nationality makes up 92 percent of China’s total population, while the remaining eight percent are represented by over 50 nationalities, including: Mongol, Hui, Tibetan, Uygur, Miao, Yi, Zhuang, Bouyei, Korean, Manchu, Kazak, and Dai. Source: About.com, travelchinaguide.com. Please refer to important information, disclosures, and qualifications at the end of this material. Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Investment Strategy Table of Contents The Chinese Dynasties Section 1 Background Page 3 Length of Period Dynasty (or period) Extent of Period (Years) Section 2 Issues for Consideration Page 65 Xia c. -

The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China

Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China Ringmar, Erik 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Ringmar, E. (2013). Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China. Palgrave Macmillan. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Part I Introduction 99781137268914_02_ch01.indd781137268914_02_ch01.indd 1 77/16/2013/16/2013 1:06:311:06:31 PPMM 99781137268914_02_ch01.indd781137268914_02_ch01.indd 2 77/16/2013/16/2013 1:06:321:06:32 PPMM Chapter 1 Liberals and Barbarians Yuanmingyuan was the palace of the emperor of China, but that is a hope lessly deficient description since it was not just a palace but instead a large com- pound filled with hundreds of different buildings, including pavilions, galleries, temples, pagodas, libraries, audience halls, and so on. -

Financial Institutions Step Forward to Save Businesses

6 | DISCOVER SHANXI Friday, March 20, 2020 CHINA DAILY Financial institutions step forward to save businesses The loan packages to the compa ny totaled 180 million yuan, accord ing to Shi. The procedure for applying for lending has been greatly stream lined. “It took only two days for the Shanxi branch of Agricultural Bank Increased lending of China to approve a loan of 50 mil to help companies lion yuan, after quickly examining The last patient of the novel coronavirus in Shanxi is cured and our financial situation and qualifi discharged from hospital on March 13. ZHANG BAOMING / FOR CHINA DAILY facing pressure cation,” Shi said. The Shanxi branches of the Agri By YUAN SHENGGAO cultural Development Bank of Chi na and Postal Saving Bank of China Province recovers fast Financial institutions in North Chi have shifted their focuses to serve na’s Shanxi province are taking steps local small and mediumsized enter to support local businesses in resum prises. ing operation by offering incentivized Tiantian Restaurant in Xiyang with all patients cured lending and facilitation measures, Employees at Pingyao Beef Group inspect products before they are county is an SME in Shanxi under according to local media reports. delivered to markets. LIU JIAQIONG / FOR CHINA DAILY great pressure. By YUAN SHENGGAO days, according to the Shanxi Since the outbreak of the novel With no business for more than a Health Commission. coronavirus epidemic, businesses in month, the company needed to pay The last patient of the novel The commission said all 117 Shanxi have faced difficulties due to While only half of the workers are interest rate of 3.15 percent. -

Representing Talented Women in Eighteenth-Century Chinese Painting: Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instruction at the Lake Pavilion

REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION By Copyright 2016 Janet C. Chen Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler ________________________________ Amy McNair ________________________________ Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Jungsil Jenny Lee ________________________________ Keith McMahon Date Defended: May 13, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Janet C. Chen certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: REPRESENTING TALENTED WOMEN IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY CHINESE PAINTING: THIRTEEN FEMALE DISCIPLES SEEKING INSTRUCTION AT THE LAKE PAVILION ________________________________ Chairperson Marsha Haufler Date approved: May 13, 2016 ii Abstract As the first comprehensive art-historical study of the Qing poet Yuan Mei (1716–97) and the female intellectuals in his circle, this dissertation examines the depictions of these women in an eighteenth-century handscroll, Thirteen Female Disciples Seeking Instructions at the Lake Pavilion, related paintings, and the accompanying inscriptions. Created when an increasing number of women turned to the scholarly arts, in particular painting and poetry, these paintings documented the more receptive attitude of literati toward talented women and their support in the social and artistic lives of female intellectuals. These pictures show the women cultivating themselves through literati activities and poetic meditation in nature or gardens, common tropes in portraits of male scholars. The predominantly male patrons, painters, and colophon authors all took part in the formation of the women’s public identities as poets and artists; the first two determined the visual representations, and the third, through writings, confirmed and elaborated on the designated identities. -

Palatial Symbolism in the Buddhist Architecture of Early Medieval China

Front. Hist. China 2015, 10(2): 222–263 DOI 10.3868/s020-004-015-0014-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Tracy Miller Of Palaces and Pagodas: Palatial Symbolism in the Buddhist Architecture of Early Medieval China Abstract This paper is an inquiry into possible motivations for representing timber-frame architecture in the Buddhist context. By comparing the architectural language of early Buddhist narrative panels and cave temples rendered in stone, I suggest that architectural representation was employed in both masonry and timber to create symbolically charged worship spaces. The replication and multiplication of palace forms on cave walls, in “pagodas” (futu 浮圖, fotu 佛圖, or ta 塔), and as the crowning element of free-standing pillars reflect a common desire to express and harness divine power, a desire that resulted in a wide variety of mountainous monuments in China. Finally, I provide evidence to suggest that the towering Buddhist monuments of early medieval China are linked morphologically and symbolically to the towering temples of South Asia through the use of both palace forms and sacred ma alas as a means to express the divine power and expansive presence of the Buddha. Keywords Pagoda, ta, mandala, Sumeru, Yicihui pillar, Yongningsi, Songyuesi From South to East Asia, from narrative relief panels to surface decoration both in caves and freestanding worship spaces, Buddhist sites are replete with depictions of timber buildings. Narrative reliefs not only allow us to read the story of the life of the Buddha, they also provide a window into the visual language of the region in which the panels were produced. -

October 20, 2010 Beijing – Jinan – Qufu – Zibo – Weifang – Yantai – Qingdao – Suzhou –Shanghai

____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Sacramento-Jinan Sister-City 25th Anniversary Trip to China October 7, 2010 – October 20, 2010 Beijing – Jinan – Qufu – Zibo – Weifang – Yantai – Qingdao – Suzhou –Shanghai Tour Highlights: ¾ Attend celebration activities in Jinan for the 25th Anniversary of Sacramento-Jinan sister- city relationship as a member of the official delegation and invited guests to Jinan ¾ Climb the Great Wall of China and see giant panda bears with your own eyes ¾ Visit the World Expo in Shanghai ¾ Learn Chinese culture through tours of gardens ¾ Tour major cities in Shandong (山东), one of the most prosperous and populous provinces of China with Jinan as its capital city and Confucius as its most illustrious son: enjoy tour of Confucius’ birthplace, wine tasting, beer museum, folk arts and ceramics, etc. For more information, please contact Grace at [email protected] or Gloria at 916.685.8049. Visit us at the City of Sacramento’s website http://www.cityofsacramento.org/sistercities/jinan.htm or our homepage www.jsscc.org. Itinerary Day 1 10/07/2010 San Francisco – Beijing Fly from San Francisco to Beijing. A full meal and beverage service will be available during this overnight flight. The International Date Line will be crossed during the flight. Day 2 10/08/2010 Beijing (北京) – Capital of China Arrive in Beijing, transfer to 4-star hotel, welcome dinner (D) Day 3 10/09/2010 Beijing Visit the Great Wall, Cloisonné Factory, Summer Palace, Beijing Olympic Park. Enjoy a Peking Duck Dinner. (B-L-D) Day 4 10/10/2010 Beijing – Jinan Tour the Tian’anmen Square, Forbidden City (The Palace Museum), Beijing Zoo. -

WEXPLORE CHINA 2011 Invitation Letter

WEXPLORE CHINA 2011 Invitation Letter Dear students and teachers, We would like to offer you a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. That is what we expect WEXPLORE China to be – an unrivalled learning experience, providing equal proportions of adventure, fun, an insight into international relations, language studies, history and cultural interaction. Not to mention the personal skills that can be gained from working with students from across the world and challenging yourself in a new and unfamiliar country. ‘New and unfamiliar’ definitely describes China. The World’s fastest growing economy is sometimes so new that a 15 years old picture is unrecognisable nowadays and last month’s road map may already be out of date! Contrastingly, another way to describe China would be ‘traditional’. In one of the oldest civilisations you will catch glimpses of the past as well as experienc- ing current practices that can be traced back thousands of years. This huge and diverse country cannot easily be defined, but one word that every visitor would agree on would be ‘fascinating’. We want you to experience as many aspects of fascinating China as possible, and this was our motivation for carefully selecting the programmes in 2011. • Beijing - 8 days discovering one of the World’s greatest cities • Shanghai and Xi’an - 6 days in the dynamic city of Shanghai, and Xi’an, the ancient capital of China • The Silk Road - a 12 day journey along the legendary trading route • Hainan - 5 days in south China’s tropical island paradise • WEMUNC 2011 - The 4th WE Model United Nations Conference, Beijing The WEMUNC (WE Model United Nations Conference) has matured over the past 4 years to become a truly international conference. -

Influence of the Silk Road Trade on the Craniofacial Morphology Of

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Influence of the Silk Road rT ade on the Craniofacial Morphology of Populations in Central Asia Ayesha Yasmeen Hinedi The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2893 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFLUENCE OF THE SILK ROAD TRADE ON THE CRANIOFACIAL MORPHOLOGY OF POPULATIONS IN CENTRAL ASIA by AYESHA YASMEEN HINEDI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 ©2018 AYESHA YASMEEN HINEDI All Rights Reserved ii Influence of the Silk Road trade on the craniofacial morphology of populations in Central Asia. by Ayesha Yasmeen Hinedi This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________ ____________________________ Date Ekatarina Pechenkina Chair of Examining Committee _____________________ _____________________________ Date Jeff Maskovsky Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: William Harcourt-Smith Felicia Madimenos Rowan Flad THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Influence of the Silk Road trade on the craniofacial morphology of populations in Central Asia. by Ayesha Yasmeen Hinedi Advisor: Ekaterina Pechenkina, Vincent Stefan. Large-scale human migrations over long periods of time are known to affect population composition.