Xanadu: Encounters with China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Wall of China the Great Wall of China Is 5,500Miles, 10,000 Li and Length Is 8,851.8Km

The Great Wall of China The Great Wall of China is 5,500miles, 10,000 Li and Length is 8,851.8km How they build the great wall is they use slaves,farmers,soldiers and common people. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/facts/ The Great Wall is made between 1368-1644. The Great Wall of China is not the biggest wall,but is the longest. http://community.travelchinaguide.com/photo-album/show.asp?aid=2278 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Is_the_Great_Wall_of_China_the_biggest_wall_in_the_world?#slide2 The Great Wall It said that there was million is so long that people were building the Great like a River. Wall and many of them lost their lives.There is even childrens had to be part of it. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/construction/labor_force.htm The Great Wall is so long that over Qin Shi Huang 11 provinces and 58 cities. is the one who start the Great Wall who decide to Start the Great Wall. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Wall_of_China http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_cities_does_the_great_wall_of_china_go_through#slide2 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_provinces_does_the_Great_Wall_of_China_go_through#slide2 Over Million people helped to build the Great Wall of China. The Great Wall is pretty old. http://facts.randomhistory.com/2009/04/18_great-wall.html There is more than one part of Great Wall There is five on the map of BeiJing When the Great Wall was build lots people don’t know where they need to go.Most of them lost their home and their part of Family. http://www.tour-beijing.com/great_wall/?gclid=CPeMlfXlm7sCFWJo7Aod- 3IAIA#.UqHditlkFxU The Great Wall is so long that is almost over all the states. -

C. R. B. Blackburn M.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.A.C.P

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.46.534.250 on 1 April 1970. Downloaded from Postgraduate Medical Journal (April 1970) 46, 250-256. Medicine in New Guinea: three and a half centuries of change C. R. B. BLACKBURN M.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.A.C.P. Department of Medicine, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia In 1502, Ludovico di Varthema set out from Italy, Peru for the west. When mutiny threatened after a joined a Persian merchant and sailed to India and landing at Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, de then through the Straits of Malacca to the Moluccas, Quiros and his ship turned back, but de Prado and the Spice Islands and Java, returning to India in others transferred to Torres' ship and visited the 1506 when the Portuguese had just defeated the Louisade Archipelago, Doini Islands, Bona Bona Arabian fleet. In Calicut he told three Portuguese and other islands and went on to the Philippines. captains who were friends, Antonio d'Abreu, They sailed along the southern coast of New Guinea Francisco Serrano and Ferdinand Magellan, about because of adverse winds and passed through the the Spice Islands. strait between Australia and New Guinea which was D'Abreu and Serrano after the conquest of named after Torres. The details of this voyage were Malacca in 1511-12 sailed to the Moluccas. lost for 150 They years. copyright. then coasted New Guinea, but did not land, and Diego de Ribera was surgeon on Torres' ship and seem to be the first Europeans to see it although was joined by Alonso Sanchez de Aranda of Seville, the Chinese and Malays knew New Guinea at least surgeon and doctor, who, with de Prado, transferred from the eighth century. -

C. Hartley Grattan

C. Hartley Grattan: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Grattan, C. Hartley (Clinton Hartley), 1902-1980 Title: C. Harley Grattan Papers Dates: circa 1920-1978 Extent: 30 record cartons (30 linear feet), 5 galley folders (gf) Abstract: Correspondence, research materials, typescript drafts, published materials, lectures and speeches, broadcast scripts, and personal items document Hartley Grattan's career from his days as a free-lance writer through his tenure as Professor of History and Curator of the Grattan Collection of Southwest Pacificana at the University of Texas at Austin, circa 1920-1978. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1700 Language: English Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. Part or all of this collection is housed off-site and may require up to three business days’ notice for access in the Ransom Center’s Reading and Viewing Room. Please contact the Center before requesting this material: [email protected] Use Policies: Ransom Center collections may contain material with sensitive or confidential information that is protected under federal or state right to privacy laws and regulations. Researchers are advised that the disclosure of certain information pertaining to identifiable living individuals represented in the collections without the consent of those individuals may have legal ramifications (e.g., a cause of action under common law for invasion of privacy may arise if facts concerning an individual's private life are published that would be deemed highly offensive to a reasonable person) for which the Ransom Center and The University of Texas at Austin assume no responsibility. -

Reminiscences of George E. Morrison; and Chinese Abroad

REMINISCENCES OF GEORGE E. MORRISON; AND CHINESE ABROAD Wu Lien-Teh, M.A., M.D. (Cantab.) Director, National Quarantine Service, China Fifth Morrison Lecture The fifth Annual Morrison Lecture departed from precedent in that it was delivered on 2nd September, 1935, instead of during the follow ing May, This ante-dating was agreed upon to take advantage of the presence in Australia of Dr. Wu Lien-teh, M.A., M.D. (Cantab). It was felt that an opportunity of hearing such a distinguished Chinese gentle man should not be missed if attendant difficulties could be surmounted. With the active co-operation of Dr. W.P. Chen arrangements were made for Dr. Wu Lien-teh to visit Canberra on Monday, 2nd September, and deliver the Morrison Lecture from 5 to 6 p.m. To a large and appreciative audience Dr. Wu gave his reminiscences of George Ernest Morrison, whom he knew intimately, and dealt with the present-day position of Chinese residents in foreign countries. Accompanying Dr. Wu to Canberra were Dr. W.P. Chen, and Mr. Narme of Sydney. Sir Colin MacKenzie, Director of the Australian Institute of Anatomy, occupied the Chair, and at the conclusion of the Lecture called on Dr. W.P. Chen to move a vote of thanks to Dr. Wu Lien teh. This was carried in the usual manner, and the audience dispersed. Owing to the alteration of the hour of the Lecture to permit Dr. Wu Lien teh to return to Sydney that night, it was not possible to hold the usual reception. 61 62 WU LIEN-TEH Address Permit me first to thank you for the honour you have done me in asking me to deliver this fifth George Ernest Morrison Lecture and even in advancing it one year so as to suit my present arrangements. -

GREAT WALL of CHINA Deconstructing

GREAT WALL OF CHINA Deconstructing History: Great Wall of China It took millennia to build, but today the Great Wall of China stands out as one of the world's most famous landmarks. Perhaps the most recognizable symbol of China and its long and vivid history, the Great Wall of China actually consists of numerous walls and fortifications, many running parallel to each other. Originally conceived by Emperor Qin Shi Huang (c. 259-210 B.C.) in the third century B.C. as a means of preventing incursions from barbarian nomads into the Chinese Empire, the wall is one of the most extensive construction projects ever completed… Though the Great Wall never effectively prevented invaders from entering China, it came to function more as a psychological barrier between Chinese civilization and the world, and remains a powerful symbol of the country’s enduring strength. QIN DYNASTY CONSTRUCTION Though the beginning of the Great Wall of China can be traced to the third century B.C., many of the fortifications included in the wall date from hundreds of years earlier, when China was divided into a number of individual kingdoms during the so-called Warring States Period. Around 220 B.C., Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, ordered that earlier fortifications between states be removed and a number of existing walls along the northern border be joined into a single system that would extend for more than 10,000 li (a li is about one-third of a mile) and protect China against attacks from the north. -

Question About Simon Leys/Pierre Ryckmans

H-Asia Question about Simon Leys/Pierre Ryckmans Discussion published by Nicholas Clifford on Friday, September 4, 2015 Sorry if this is going to the wrong place, but it's the sort of relatively simple question that it was possible to ask on H-ASIA in its earlier incarnation. Is this the appropriate place to put it? and if not, where should I try? Many thanks. I'm trying to find out exactly when "Simon Leys" was publically identified as "Pierre Ryckmans," at the time of his arguments with a powerful group of French academic Maoists. His Habits neufs du président Mao (The Chairman’s New Clothes) a chronicle of the Cultural Revolution, written in Hong Kong and based on the Chinese press and other sources) came out in France in 1971. Then, after a stay of six months in Beijing attached to the new Belgian embassy, he wrote Ombres chinoises (Chinese Shadows) which appeared in 1974. In 1975-76 he had a tussle with the French scholar Michelle Loi, whose primary interest lay in Lu Xun (whom Leys admired enormously, as he did George Orwell). In 1976 she published (in Switzerland) a brief pamphlet called Pour Luxun: réponse à Pierre Ryckmans (For Lu Xun: reply to Pierre Ryckmans) attacking him and his views on China and linking him to reactionary circles in American China studies, and those Americans who (she says) actually preferred Zhou Zuoren (Lu Xun’s collaborationist brother) to Lu Xun himself. She herself, though admitting the problems the CCP gave Lu Xun prior to his death in 1936, managed to put the blame not on Mao and the Maoists, but on Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Yang, and some of the others who were disgraced during the Cultural Revolution, and had not yet been rehabilitated at the time of her writing. -

OPERA, COMIC OPERA, MUSICAL Box 4/1

Enid Robertson Theatre Programme Collection MSS 792 T3743.R OPERA, COMIC OPERA, MUSICAL Box 4/1 Artist Date Venue, notes Melba, Dame Nellie, with Frederic Griffith 12.11.1902 Direction Mr George (Flute), Llewela Davies (Piano) M. (Second Musgrove Bensaude (Vocal) Signorina Sassoli Concert:15.11) Town Hall, Adelaide (Harp)Louis Arens, (Vocal)Dr. F. Matthew Ennis (Piano) Handel, Thomas, Arditi. Melba, Dame Nellie with, Tom Burke 15.6.1919 Royal Albert Hall, (Tenor), Bronislaw Huberman (Violin) London Frank St. Leger (Piano) Arthur Mason (Organ) Verdi, Puccini, etc. Melba, Dame Nellie 4.10.1921 Manager, John Lemmone, With Una Bourne (Piano), W.F.G.Steele (Second Concert Town Hall, Adelaide (Organ), John Lemmone (Flute) Mozart, 6.10.21) Verdi Melba, Dame Nellie & J.C. Williamson 26.9.1924 Direction, Nevin Tait Grand Opera Season , Aida (Verdi) Theatre Royal Adelaide Conductor Franco Paolantonio, with Augusta Concato, Phyllis Archibald, Nino Piccaluga, Edmondo Grandini, Gustave Huberdeau, Oreste Carozzi Melba, Dame Nellie & J.C. Williamson, 4.10.1924 Direction, Nevin Tait Grand Opera Season, Andrea Chenier, Theatre Royal Adelaide (Giordano) First Adelaide Performance, Franco Paolantonio (Conductor) Nino Piccaluga, Apollo Granforte, Doris McInnes, Antonio Laffi, Oreste Carozzi, Gaetano Azzolini, Luigi Cilla, Luigi Parodi, Antonio Venturi, Alfredo Muro, Vanni Cellini Melba, Dame Nellie & J.C. Williamson, 6.10.1924 Direction, Nevin Tait Grand Opera Season, DonPasquale, Theatre Royal, Adelaide (Donizetti) First Performance in Adelaide, Arnaldo -

Annual Review 2017–2018

Australia-China Institute for Arts and Culture Annual Review 2017–2018 ANNUAL REVIEW 2017–2018 Vision Statement China’s rapid emergence as a ACIAC positions itself as a hub and global economic and political national resource centre for cultural power is reshaping the world. For exchange between Australia, Australia, this means an urgent China and the Sinosphere, and for need to know about it not just as collaborative action in the arts and its largest trading partner but other cultural fields. It will build on as a centuries old neighboring the strengths of Western Sydney culture, and learn to engage with University and on existing exchange it in a culturally smart way. The programs in the University. It will Australia-China Institute for Arts help enhance existing exchanges and Culture (ACIAC) was founded between the University and partner for the purpose of facilitating this universities overseas, particularly need. ACIAC also offers to help in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong forge bilateral understanding Kong and Singapore. It will launch between the two peoples and significant new research programs enable development of deeper ties of relevance to the Australia-China between the two countries through relationship, and will engage with the an open, intellectual and dynamic local community in Western Sydney engagement. and particularly with ethnic Chinese groups, businesses and individuals and seek support to ensure its long- term future. Artwork by Shen Wednesday westernsydney.edu.au/aciac 3 AUSTRALIA-CHINA INSTITUTE FOR ARTS AND CULTURE Director’s Report The year of 2018 has been a time of steady completed during the year,and they are The Institute has, through its multiple events, growth for the Australia-China Institute for research fellow Dr Xiang Ren’s internationally turned itself into an important base for Arts and Culture. -

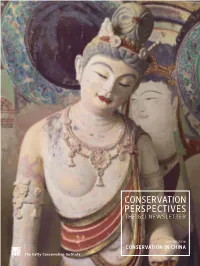

Conservation in China Issue, Spring 2016

SPRING 2016 CONSERVATION IN CHINA A Note from the Director For over twenty-five years, it has been the Getty Conservation Institute’s great privilege to work with colleagues in China engaged in the conservation of cultural heritage. During this quarter century and more of professional engagement, China has undergone tremendous changes in its social, economic, and cultural life—changes that have included significant advance- ments in the conservation field. In this period of transformation, many Chinese cultural heritage institutions and organizations have striven to establish clear priorities and to engage in significant projects designed to further conservation and management of their nation’s extraordinary cultural resources. We at the GCI have admiration and respect for both the progress and the vision represented in these efforts and are grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage in China. The contents of this edition of Conservation Perspectives are a reflection of our activities in China and of the evolution of policies and methods in the work of Chinese conservation professionals and organizations. The feature article offers Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI a concise view of GCI involvement in several long-term conservation projects in China. Authored by Neville Agnew, Martha Demas, and Lorinda Wong— members of the Institute’s China team—the article describes Institute work at sites across the country, including the Imperial Mountain Resort at Chengde, the Yungang Grottoes, and, most extensively, the Mogao Grottoes. Integrated with much of this work has been our participation in the development of the China Principles, a set of national guide- lines for cultural heritage conservation and management that respect and reflect Chinese traditions and approaches to conservation. -

Issue, Find a Full List of Distribution Points for Hard Copies Or Arrange a Subscription to Have the Nanjinger Delivered to Your Home Or Office!

MAY 2021 www.thenanjinger.com 6 Sign of the Times hat it’s been more than a year since our 1. How have you felt lately (like over the last outing in “The Trip” is indeed a sign past year); anxious or guilty? See p. 16-18. Tof these days. 2. Should you bother to keep pace in the But we’re back with a vengeance. And we’ll Chinese race to be ever-more “beautiful”? wager that you too will be hunkering for the See p. 10-12. clean air of Chizhou and the splendour of 3. Taken out a gym membership recently? Jiuhua Shan after you’re read our first travel Notice anything strange? See p. 14-15. piece of 2021. See p. 22-23. Welcome to “Zeitgeist” from The Nanjinger. But before that, a few questions to get us started for this month. Ed. can the QR Code to visit The Nanjinger on WeChat, from where Syou can download a free PDF of this issue, find a full list of distribution points for hard copies or arrange a subscription to have The Nanjinger delivered to your home or office! This magazine is part of a family of English publications that together reach a large proportion of the foreign population living in Nanjing, along with a good dash of locals, comprising: The Nanjinger City Guide www.thenanjinger.com Facebook, WeChat, Twitter & Instagram All of the above are owned and operated by HeFu Media, the Chinese subsidiary of SinoConnexion Ltd;www.sinoconnexion.com 2 By Maitiu Bralligan ‘21 Independently, we each rebelled in such similar ways: Black clothes, long hair, earring in the left ear Listening to the same riffs and the same bars “And now you do what they told ya...” We were free! Casting our fearless bodies Into the mosh pit / wrecking pool (call it what you will) In the thrall of the same intoxicating thrill. -

The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE HALL OF USELESSNESS: COLLECTED ESSAYS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Simon Leys | 464 pages | 02 Dec 2012 | Black Inc. | 9781863955850 | English | Melbourne, Australia The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays PDF Book What made Leys most remarkable was his depth, his continuous effort to try to get to the bottom of things, to understand them, and to render them with the great simplicity proper of the people who really worked through them. Maeve Binchy. How Did I Get Here? Simon Leys died just short of two years ago. Simon Leys is one writer who is possessed of intelligence, wide learning, facility for the written word, and a clear minded logic that cuts through to the core of the matter. After his imprisonment on St Helena in , Napoleon manages to escape, having left an imposter, a close double, in his place. We are experiencing technical difficulties. I imagine Simon would have very little patience for the no-sacrifice, lip-service, sentimentality posing as critical thinking and actual involvement that seems to be all the rage today, facilitated as it is by the bully-pulpit-in-every- pot, medium of the internet. Continuity is not ensured by the immobility of inanimate objects, it is achieved through the fluidity of the successive generations. These are matched with his own highly-quotable phrases, sentences and whole paragraphs. If one did not already come to the conclusion from what I have just written, let me point out that Leys was also a Christian. Rarer still that that person would be a translator of Chinese. This collection is a collection of all of Leys' finest es Simon Leys or Pierre Ryckmans was a Belgian-Australian writer, professor of Chinese literature at University of Sydney, translator, sinologist and, frankly, an all round man of the arts. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 35,1915-1916, Trip

SANDERS THEATRE . CAMBRIDGE HARVARD UNIVERSITY ^\^><i Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor ITTr WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 23 AT 8.00 COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 1 €$ Yes, It's a Steinway ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to I you. and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extra dollars and got a Steinway." pw=a I»3 ^a STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Violins. Witek, A. Roth, O. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet. H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Sulzen, H.