Great Wall of China Ebcid:Com.Britannica.Oec2.Identifier.Articleidentifier?Tocid=9037891&Ar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Great Wall of China the Great Wall of China Is 5,500Miles, 10,000 Li and Length Is 8,851.8Km

The Great Wall of China The Great Wall of China is 5,500miles, 10,000 Li and Length is 8,851.8km How they build the great wall is they use slaves,farmers,soldiers and common people. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/facts/ The Great Wall is made between 1368-1644. The Great Wall of China is not the biggest wall,but is the longest. http://community.travelchinaguide.com/photo-album/show.asp?aid=2278 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Is_the_Great_Wall_of_China_the_biggest_wall_in_the_world?#slide2 The Great Wall It said that there was million is so long that people were building the Great like a River. Wall and many of them lost their lives.There is even childrens had to be part of it. http://www.travelchinaguide.com/china_great_wall/construction/labor_force.htm The Great Wall is so long that over Qin Shi Huang 11 provinces and 58 cities. is the one who start the Great Wall who decide to Start the Great Wall. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Wall_of_China http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_cities_does_the_great_wall_of_china_go_through#slide2 http://wiki.answers.com/Q/How_many_provinces_does_the_Great_Wall_of_China_go_through#slide2 Over Million people helped to build the Great Wall of China. The Great Wall is pretty old. http://facts.randomhistory.com/2009/04/18_great-wall.html There is more than one part of Great Wall There is five on the map of BeiJing When the Great Wall was build lots people don’t know where they need to go.Most of them lost their home and their part of Family. http://www.tour-beijing.com/great_wall/?gclid=CPeMlfXlm7sCFWJo7Aod- 3IAIA#.UqHditlkFxU The Great Wall is so long that is almost over all the states. -

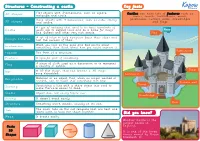

KO DT Y3 Castles

Structures - Constructing a castle Key facts Flat objects with 2-dimensions, such as square, 2D shapes Castles can have lots of features such as rectangle and circle. towers, turrets, battlements, moats, Solid objects with 3-dimensions, such as cube, oblong gatehouses, curtain walls, drawbridges 3D shapes and sphere. and flags. A type of building that used to be built hundreds of Castle years ago to defend land and be a home for Kings and Queens and other very rich people. Flag A set of rules to help designers focus their ideas and Design criteria test the success of them. When you look at the good and bad points about Evaluation something, then think about how you could improve it. Battlement Façade The front of a structure. Feature A specific part of something. Flag A piece of cloth used as a decoration or to represent a country or symbol. Tower Net A 2D flat shape, that can become a 3D shape once assembled. Gatehouse Recyclable Material or an object that, when no longer wanted or needed, can be made into something else new. Curtain wall Turret Scoring Scratching a line with a sharp object into card to make the card easier to bend. Stable Object does not easily topple over. Drawbridge Strong It doesn't break easily. Moat Structure Something which stands, usually on its own. Tab The small tabs on the net template that are bent and glued down to hold the shape together. Did you know? Weak It breaks easily. Windsor Castle is the largest castle in Basic England. -

Independent Age Great Wall Trek

Asia independent age great wall trek trip highligh ts Walking through rural villages in the Hebei Province Sleep in a comfortable guest house and traditional inn close to the Great Wall Rare insight into rural Chinese life Exploring original sections of the Great Wall Visiting Tiananmen Square, Forbidden City Spending time with your fellow Independent Age supporters Trip Duration 9 days Trip Code: SOG5116 Grade Introductory to Moderate Activities Trekking, Adventure Touring Summary 9 day trip, 5 day trek, 3 nights hotel, 4 nights comfortable guest house welcome to why travel with World Expeditions? We have built a reputation in the charity travel industry as a trusted World Expeditions company and many charities large and small return to us again and Thank you for your interest in our Independent Age Great Wall Trek again to organise their challenges. We have many years of experience trip. At World Expeditions we are passionate about our off the beaten working with charities of all sizes to offer the best experiences for track experiences as they provide our travellers with the thrill of the very best value for money with safety as the number one priority. coming face to face with untouched cultures as well as wilderness We are a small team here in London and therefore your trip will be regions of great natural beauty. We are committed to ensuring that organised by the same person, to keep things simple, and to maintain our unique itineraries are well researched, affordable and tailored for customer service as one of our priorities. We have also worked with a the enjoyment of small groups or individuals ‑ philosophies that have number of prominent charities such as Save The Children and Marie been at our core since 1975 when we began operating adventure Curie so we also know what all groups require in terms of health and holidays. -

旅游减贫案例2020(2021-04-06)

1 2020 世界旅游联盟旅游减贫案例 WTA Best Practice in Poverty Alleviation Through Tourism 2020 Contents 目录 广西河池市巴马瑶族自治县:充分发挥生态优势,打造特色旅游扶贫 Bama Yao Autonomous County, Hechi City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region: Give Full Play to Ecological Dominance and Create Featured Tour for Poverty Alleviation / 002 世界银行约旦遗产投资项目:促进城市与文化遗产旅游的协同发展 World Bank Heritage Investment Project in Jordan: Promote Coordinated Development of Urban and Cultural Heritage Tourism / 017 山东临沂市兰陵县压油沟村:“企业 + 政府 + 合作社 + 农户”的组合模式 Yayougou Village, Lanling County, Linyi City, Shandong Province: A Combination Mode of “Enterprise + Government + Cooperative + Peasant Household” / 030 江西井冈山市茅坪镇神山村:多项扶贫措施相辅相成,让山区变成景区 Shenshan Village, Maoping Town, Jinggangshan City, Jiangxi Province: Complementary Help-the-poor Measures Turn the Mountainous Area into a Scenic Spot / 038 中山大学: 旅游脱贫的“阿者科计划” Sun Yat-sen University: Tourism-based Poverty Alleviation Project “Azheke Plan” / 046 爱彼迎:用“爱彼迎学院模式”助推南非减贫 Airbnb: Promote Poverty Reduction in South Africa with the “Airbnb Academy Model” / 056 “三区三州”旅游大环线宣传推广联盟:用大 IP 开创地区文化旅游扶贫的新模式 Promotion Alliance for “A Priority in the National Poverty Alleviation Strategy” Circular Tour: Utilize Important IP to Create a New Model of Poverty Alleviation through Cultural Tourism / 064 山西晋中市左权县:全域旅游走活“扶贫一盘棋” Zuoquan County, Jinzhong City, Shanxi Province: Alleviating Poverty through All-for-one Tourism / 072 中国旅行社协会铁道旅游分会:利用专列优势,实现“精准扶贫” Railway Tourism Branch of China Association of Travel Services: Realizing “Targeted Poverty Alleviation” Utilizing the Advantage -

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof

Protection and Transmission of Chinese Nanyin by Prof. Wang, Yaohua Fujian Normal University, China Intangible cultural heritage is the memory of human historical culture, the root of human culture, the ‘energic origin’ of the spirit of human culture and the footstone for the construction of modern human civilization. Ever since China joined the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2004, it has done a lot not only on cognition but also on action to contribute to the protection and transmission of intangible cultural heritage. Please allow me to expatiate these on the case of Chinese nanyin(南音, southern music). I. The precious multi-values of nanyin decide the necessity of protection and transmission for Chinese nanyin. Nanyin, also known as “nanqu” (南曲), “nanyue” (南乐), “nanguan” (南管), “xianguan” (弦管), is one of the oldest music genres with strong local characteristics. As major musical genre, it prevails in the south of Fujian – both in the cities and countryside of Quanzhou, Xiamen, Zhangzhou – and is also quite popular in Taiwan, Hongkong, Macao and the countries of Southeast Asia inhabited by Chinese immigrants from South Fujian. The music of nanyin is also found in various Fujian local operas such as Liyuan Opera (梨园戏), Gaojia Opera (高甲戏), line-leading puppet show (提线木偶戏), Dacheng Opera (打城戏) and the like, forming an essential part of their vocal melodies and instrumental music. As the intangible cultural heritage, nanyin has such values as follows. I.I. Academic value and historical value Nanyin enjoys a reputation as “a living fossil of the ancient music”, as we can trace its relevance to and inheritance of Chinese ancient music in terms of their musical phenomena and features of musical form. -

The Second Circular

The 24th World Congress of Philosophy Title: The XXIV World Congress of Philosophy (WCP2018) Date: August 13 (Monday) - August 20 (Monday) 2018 Venue: Peking University, Beijing, P. R. China Official Language: English, French, German, Spanish, Russian, Chinese Congress Website: wcp2018.pku.edu.cn Program: Plenary Sessions, Symposia, Endowed Lectures, 99 Sections for Contributed Papers, Round Tables, Invited Sessions, Society Sessions, Student Sessions and Poster Sessions Organizers: International Federation of Philosophical Societies Peking University CONFUCIUS Host: Chinese Organizing Committee of WCP 2018 Important Dates Paper Submission Deadline February 1, 2018 Proposal Submission Deadline February 1, 2018 Early Registration October 1, 2017 On-line Registration Closing June 30, 2018 On-line Hotel Reservation Closing August 6, 2018 Tour Reservation Closing June 30, 2018 * Papers and proposals may be accepted after that date at the discretion of the organizing committee. LAO TZE The 24th World Congress of Philosophy MENCIUS CHUANG TZE CONTENTS 04 Invitation 10 Organization 17 Program at a Glance 18 Program of the Congress 28 Official Opening Ceremony 28 Social and Cultural Events 28 Call for Papers 30 Call for Proposals WANG BI HUI-NENG 31 Registration 32 Way of Payment 32 Transportation 33 Accommodation 34 Tours Proposals 39 General Information CHU HSI WANG YANG-MING 02 03 The 24th World Congress of Philosophy Invitation WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT OF FISP Chinese philosophy represents a long, continuous tradition that has absorbed many elements from other cultures, including India. China has been in contact with the scientific traditions of Europe at least since the time of the Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), who resided at the Imperial court in Beijing. -

GREAT WALL of CHINA Deconstructing

GREAT WALL OF CHINA Deconstructing History: Great Wall of China It took millennia to build, but today the Great Wall of China stands out as one of the world's most famous landmarks. Perhaps the most recognizable symbol of China and its long and vivid history, the Great Wall of China actually consists of numerous walls and fortifications, many running parallel to each other. Originally conceived by Emperor Qin Shi Huang (c. 259-210 B.C.) in the third century B.C. as a means of preventing incursions from barbarian nomads into the Chinese Empire, the wall is one of the most extensive construction projects ever completed… Though the Great Wall never effectively prevented invaders from entering China, it came to function more as a psychological barrier between Chinese civilization and the world, and remains a powerful symbol of the country’s enduring strength. QIN DYNASTY CONSTRUCTION Though the beginning of the Great Wall of China can be traced to the third century B.C., many of the fortifications included in the wall date from hundreds of years earlier, when China was divided into a number of individual kingdoms during the so-called Warring States Period. Around 220 B.C., Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, ordered that earlier fortifications between states be removed and a number of existing walls along the northern border be joined into a single system that would extend for more than 10,000 li (a li is about one-third of a mile) and protect China against attacks from the north. -

Global Archive UAP-Study and UFO-Identification Глобальный Архив НЛО-Отождествления И ААЯ-Исследования

Global archive UAP-study and UFO-identification Глобальный архив НЛО-отождествления и ААЯ-исследования Version 1.5 Period of work (Период работ) 1.0: 30.01.2011-14.07.2012 (+65,4gb) Period of work (Период работ) 1.1: 23.07.2012-23.08.2012 (+26,9gb) Period of work (Период работ) 1.2: 01.10.2012-06.10.2012 (+01,6gb) Period of work (Период работ) 1.3: 03.01.2013-25.01.2013 (+14,2gb) Period of work (Период работ) 1.4: 23.04.2013-07.05.2013 (+08,5gb) Period of work (Период работ) 1.5: 03.07.2013-10.07.2013 (+03,5gb) This was achieved by back-breaking work, spending all free time working day by day, moving toward the goal with aspiration - for the future of mankind. History of UFO identification and UAP research is also our history, of each of us and all mankind, which is worth of paying attention. We remember - it was, it can't be deleted, it's memory which needs to be protected. Yours sincerelly, Igor Kalytyuk Этого удалось достичь непосильным трудом, тратя на это все свое свободное время, работая над этим день за днем, устремленно двигаясь к поставленной цели – ради будущего человечества. История НЛО-отождествления и ААЯ-исследования, это тоже наша история, как каждого из нас, так и всего человечества, которая стоит чтобы этому уделяли внимание, мы помним – это было, это не вычеркнешь, это память, что нуждается в защите. С уважением, искренне Ваш Игорь Калытюк Creators Kalytyuk Igor - Born 25.10.1987 in Ukraine. He have a two honors diploma in economics and computer science. -

Sundowners Overland

Journey Itinerary The Frosty Flyer Days Eastbound Countries Distance Activity level 19 St. Petersburg to Beijing Russia + Mongolia + China 8,515 km An epic winter adventure that’s not for the fainthearted! Leave the North Pole to Santa and get yourself to Siberia for a winter adventure you’ll never forget. Enjoy adrenaline fuelled activities amid glistening landscapes. Warm up in a Russian sauna and try your hand at cooking dumplings in a cosy ger camp. And best of all, see the iconic sights sans tourists, like the Great Wall dusted in freshly fallen snow. Vodkatrain - The Frosty Flyer Page 1 of 7 Itinerary Day 1: St. Petersburg Arrive in St. Petes and meet your fellow adventurers. Perhaps begin with a wander along the frozen Neva river or canals – parents will be teaching their little ones to skate on the picturesque waterways that weave through the city. Descend into underground palaces on the metro and find yourself surrounded by marble pillars, ornate chandeliers and classical frescos. Stroll down Nevsky Prospect, and take in the magnificence of the Church of the Saviour on Spilled Blood. Visit the Hermitage Museum, in the suitably named Winter Palace, for a taste of Tsar life. Get immersed in the thriving culture as you discover an experimental art scene, cosy wine bars, great tea houses and a multicultural food offering, then party all night in live music venues and pulsating clubs. A local punk musician recently summed up the scene by saying “in a city of three revolutions, you’re bound to get a fourth”. Day 2: St. -

Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880S-1940S

Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hashimoto, Satoru. 2014. Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13064962 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s A dissertation presented by Satoru Hashimoto to The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of East Asian Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2014 ! ! © 2014 Satoru Hashimoto All rights reserved. ! ! Dissertation Advisor: Professor David Der-Wei Wang Satoru Hashimoto Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s Abstract This dissertation examines how modern literature in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan in the late-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries was practiced within contexts of these countries’ deeply interrelated literary traditions. -

漢基控股有限公司* (Incorporated in Bermuda with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 412) R13.51A (Warrant Code: 1248)

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt about any aspect of this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should R14.63(2b) consult your licensed securities dealer or registered institution in securities, bank manager, solicitor, certified public accountant or other professional advisers. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in Heritage International Holdings Limited (“Company”), you should at once hand this circular together with the enclosed form of proxy to the purchaser or transferee or to licensed securities dealer or registered institution in securities or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no R14.58(1) responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. HERITAGE INTERNATIONAL HOLDINGS LIMITED App1B 1 漢基控股有限公司* (Incorporated in Bermuda with limited liability) (Stock Code: 412) R13.51A (Warrant Code: 1248) MAJOR TRANSACTION IN RELATION TO ACQUISITION OF THE ENTIRE ISSUED SHARE CAPITAL OF GLOBAL CASTLE INVESTMENTS LIMITED AND NOTICE OF SPECIAL GENERAL MEETING A notice convening the SGM to be held at 30/F., China United Centre, 28 Marble Road, North Point, Hong Kong on Thursday, 28 March 2013 at 9:00 a.m. is set out on pages SGM-1 to SGM-2 of this circular. -

Castle Structure and Function

Vocabulary Castle Structure and Function Name: Date: Castle Use A Castle’s Structure: · Large and of great defensive strength · Surrounded by a wall with a fighting platform · Usually has a large, strong tower A Castle’s Function: · Fortress and military protection · Center of local government · Home of the owner, usually a king The Parts of a Castle allure: the walkway at the top of a castle wall. The allure was often shielded by a protective wall so that guards could move between towers; also called a wall-walk arcading: a series of columns and arches, built in an upside-down U shape arrow loop: a tiny vertical opening in the castle wall; a thin window used for shooting arrows at the enemy; also called a loophole or meurtriere ashlar: blocks of stone, used to build castle wa lls and towers bailey: an open, grassy area inside the walls of the castle containing farm pastures, cottages, and other buildings. Sometimes a castle had more than one bailey; also called a ward. balustrade: railing along a path or stairway barrel vault: semicircular roof made out of wood or stone bastion: a small tower on a courtyard wall or an outside wall battlement: a narrow wall built along the outer edge of the wall-walk to protect soldiers against attack boss: the middle stone in an arch; also called a keystone concentric: having two sets of walls, one inside the other cornerstone: a stone at the corner of a building uniting two intersecting walls, sometimes inscribed with the year the building was constructed; also called a quoin crosswall: a wall inside a large tower Lesson Connection: Castles and Cornerstones Copyright The Kennedy Center.