Vienna's Transnational Fringe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November/Dezember 06 Gift – November/Dezember 06

ÖÖsterreichischesterreichische PPostost AAGG gift IInfo.Mailnfo.Mail EEntgeltntgelt bbezahltezahlt zeitschrift für freies theater Thema: Precarious Performances „Das Prekäre fungiert also als Schnittstelle von Ästhetik und dem Sozio-Politischen, es zirkuliert in der performativen Schleife zwischen Theater und anderen Realitäten.“ Katharina Pewny november/dezember 06 gift – november/dezember 06 Inhalt editorial thema 22 Precarious Performances aktuell 23 Freiheit in Kunst und Kultur I 4 Veranstaltungsankündigungen 27 Das Prekäre performen 5 Printspielplan Wien in Gefahr 30 Ideology performs ... 5 European Off Network 33 Theatre and War in Kosova 6 theaterspielplan.at on tour 39 Performing in a precarious reality 7 Onlineticketing bei theaterspielplan.at debatte politik 43 Roundtable Tanz und Performance 8 Kulturrat Österreich 10 Pfl egefall Salzburger Kulturszene service 12 Theaterreform Wien 46 Intern 14 Kulturfi nanzierung des Bundes 2005 46 News 48 Ausschreibungen diskurs 49 Festivals 16 Räume 50 Veranstaltungen 18 Von Wien nach Luxemburg 20 Freies Theater in den Medien premieren editorial Liebe Theaterschaffende, liebe LeserInnen, Statt der gift hat Sie/ euch Anfang September die Zeitung des Unsere italienischen Partnern ist es gelungen, im kommenden Kulturrats Österreich zur Nationalratswahl erreicht – eine Jahr vom 10. bis 13. Mai in Brescia wieder ein großes Euro- gemeinsame kulturpolitische Initiative aller IGs mit nicht un- pean Off Network Treffen im Rahmen des IKOS Festival auf beträchtlicher Wirkung, die jedoch keine Information zum die Beine zu stellen, zu dem wir schon jetzt alle Interessierten freien Theater ersetzt. sehr herzlich einladen möchten: Frauen im freien Theater/ Verspätet willkommen heute also auf dem Weg in kultur- Freies Theater in Zeiten des Krieges/ „Entkörperung“ und politisch neue Verhältnisse, in einer neuen Saison, mit einer Re-Empowerment des Körpers im freien Theater/ Nachhaltige neuen „Identität“ auch unserer Zeitung! Netzwerkarbeit lauten die bislang verabredeten Themen. -

The Blitz and Its Legacy

THE BLITZ AND ITS LEGACY 3 – 4 SEPTEMBER 2010 PORTLAND HALL, LITTLE TITCHFIELD STREET, LONDON W1W 7UW ABSTRACTS Conference organised by Dr Mark Clapson, University of Westminster Professor Peter Larkham, Birmingham City University (Re)planning the Metropolis: Process and Product in the Post-War London David Adams and Peter J Larkham Birmingham City University [email protected] [email protected] London, by far the UK’s largest city, was both its worst-damaged city during the Second World War and also was clearly suffering from significant pre-war social, economic and physical problems. As in many places, the wartime damage was seized upon as the opportunity to replan, sometimes radically, at all scales from the City core to the county and region. The hierarchy of plans thus produced, especially those by Abercrombie, is often celebrated as ‘models’, cited as being highly influential in shaping post-war planning thought and practice, and innovative. But much critical attention has also focused on the proposed physical product, especially the seductively-illustrated but flawed beaux-arts street layouts of the Royal Academy plans. Reconstruction-era replanning has been the focus of much attention over the past two decades, and it is appropriate now to re-consider the London experience in the light of our more detailed knowledge of processes and plans elsewhere in the UK. This paper therefore evaluates the London plan hierarchy in terms of process, using new biographical work on some of the authors together with archival research; product, examining exactly what was proposed, and the extent to which the different plans and different levels in the spatial planning hierarchy were integrated; and impact, particularly in terms of how concepts developed (or perhaps more accurately promoted) in the London plans influenced subsequent plans and planning in the UK. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

View Program

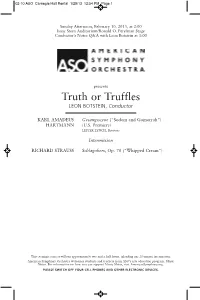

02-10 ASO_Carnegie Hall Rental 1/29/13 12:54 PM Page 1 Sunday Afternoon, February 10, 2013, at 2:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 1:00 presents Truth or Truffles LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor KARL AMADEUS Gesangsszene (“Sodom and Gomorrah”) HARTMANN (U.S. Premiere) LESTER LYNCH, Baritone Intermission RICHARD STRAUSS Schlagobers, Op. 70 (“Whipped Cream”) This evening’s concert will run approximately two and a half hours, inlcuding one 20-minute intermission. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes students and teachers from ASO’s arts education program, Music Notes. For information on how you can support Music Notes, visit AmericanSymphony.org. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. 02-10 ASO_Carnegie Hall Rental 1/29/13 12:54 PM Page 2 THE Program KARL AMADEUS HARTMANN Gesangsszene Born August 2, 1905, in Munich Died December 5, 1963, in Munich Composed in 1962–63 Premiered on November 12, 1964, in Frankfurt, by the orchestra of the Hessischer Rundfunk under Dean Dixon with soloist Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, for whom it was written Performance Time: Approximately 27 minutes Instruments: 3 flutes, 2 piccolos, alto flute, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 3 French horns, 3 trumpets, piccolo trumpet, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, gong, chimes, cymbals, tamtam, tambourine, tomtoms, timbales, field drum, snare drum, bass drum, glockenspiel, xylophone, vibraphone, marimba), harp, celesta, piano, strings, -

Operetta After the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen a Dissertation

Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Elaine Tennant Spring 2013 © 2013 Ulrike Petersen All Rights Reserved Abstract Operetta after the Habsburg Empire by Ulrike Petersen Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Richard Taruskin, Chair This thesis discusses the political, social, and cultural impact of operetta in Vienna after the collapse of the Habsburg Empire. As an alternative to the prevailing literature, which has approached this form of musical theater mostly through broad surveys and detailed studies of a handful of well‐known masterpieces, my dissertation presents a montage of loosely connected, previously unconsidered case studies. Each chapter examines one or two highly significant, but radically unfamiliar, moments in the history of operetta during Austria’s five successive political eras in the first half of the twentieth century. Exploring operetta’s importance for the image of Vienna, these vignettes aim to supply new glimpses not only of a seemingly obsolete art form but also of the urban and cultural life of which it was a part. My stories evolve around the following works: Der Millionenonkel (1913), Austria’s first feature‐length motion picture, a collage of the most successful stage roles of a celebrated -

Nexus Nexus Star

NEXUS English NEXUS STAR References AUDIO EXCELLENCE NEXUS, NEXUS Star TV and Radio Broadcast • 20th Century Fox LA, USA • RBB FS Berlin, Germany • ABC News Los Angeles, USA • RPP Radio Programas del Peru Lima, Peru • All India Radio New Delhi, India • RTL Studio Berlin, Germany • Anhui TV Hefei-Anhui, China • RTL 2 Paris, France • Antena 3 TV Madrid, Islas Baleares, Spain • SAT 1 Zurich, Switzerland • ASTRO Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia • Shanghai Education Television Shanghai, China • BBC Transmission Router London, United Kingdom • SFB Sender Freies Berlin Berlin, Germany • BBC North Manchester, United Kingdom • SR Saarländischer Rundfunk Saarbrücken, Germany • Bernama News TV Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia • Staatlicher Rundfunk Usbekistan Uzbekistan • BFM Radio Paris, France • Star RFM Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia • BR Bayerischer Rundfunk Munich, Germany • Studio Hamburg Hamburg, Germany • Cadena SER Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Spain • SWR Südwestrundfunk Stuttgart, Baden-Baden, • Canal Mundo Radio Madrid, Spain Germany • Canal+ Paris, France • Tele 5 Madrid, Spain • CBC Cologne Broadcasting Center Cologne, Germany • Tele Red Imagen Buenos Aires, Argentina • CBS New York, USA • Television Autonomica Valenciana Valencia, Spain • Chong-Qin TV Chong-Qin, China • TF 1 Paris, France • City FM Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia • TV 1 Napoli Naples, Italy • City Plus Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia • TV Tokyo Tokyo, Japan • ESPN Bristol, LA, USA • TVE Radio Televisión Espanola Madrid, Spain • ETABETA Rome, Italy • Unitel Unterföhring, Germany • Eurosport 2 Paris, France • Vatican -

Kulturstatistik 2017 – Zusammenfassung

2017 KULTURSTATISTIK Herausgegeben von STATISTIK AUSTRIA Wien 2019 Impressum Auskünfte Für schriftliche oder telefonische Anfragen steht Ihnen in der Statistik Austria der Allgemeine Auskunftsdienst unter der Adresse Guglgasse 13 1110 Wien Tel.: +43 (1) 711 28-7070 e-mail: [email protected] Fax: +43 (1) 71128-7728 zur Verfügung. Herausgeber und Hersteller STATISTIK AUSTRIA Bundesanstalt Statistik Österreich 1110 Wien Guglgasse 13 Für den Inhalt verantwortlich Mag. Wolfgang Pauli Tel.: +43 (1) 711 28-7268 e-mail: [email protected] Umschlagfoto Cäcilia Bachmann Kommissionsverlag Verlag Österreich GmbH 1010 Wien Bäckerstraße 1 Tel.: +43 (1) 610 77-0 e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-3-903264-22-9 Das Produkt und die darin enthaltenen Daten sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Alle Rechte sind der Bundesanstalt Statistik Österreich (STATISTIK AUSTRIA) vorbehalten. Bei richtiger Wiedergabe und mit korrekter Quellenangabe „STATISTIK AUSTRIA“ ist es gestattet, die Inhalte zu vervielfältigen, verbreiten, öffentlich zugänglich zu machen und sie zu bearbeiten. Bei auszugsweiser Verwendung, Darstellung von Teilen oder sonstiger Veränderung von Dateninhalten wie Tabellen, Grafiken oder Texten ist an geeigneter Stelle ein Hinweis anzubrin- gen, dass die verwendeten Inhalte bearbeitet wurden. Die Bundesanstalt Statistik Österreich sowie alle Mitwirkenden an der Publikation haben deren Inhalte sorgfältig recher- chiert und erstellt. Fehler können dennoch nicht gänzlich ausgeschlossen werden. Die Genannten übernehmen daher keine -

Broadcasting

Broadcasting tpc zürich ag: sport studio; control room 1, 2, 3, VR1, VR2 Zurich, Switzerland TSR Télévision Suisse Romande Geneva, Switzerland References: AURUS & NEXUS/NEXUS STAR TVE Radio Televisión Espanola: A4 Studio, Studio 10 + 11 Madrid, Spain Antena 3 Madrid (TV) Madrid, Spain (9 Main Consoles) WDR Westdeutscher Rundfunk: »Philharmonic Hall«; dubbing studio Astro (Malaysian satellite television): HD Sport channel; U+V (2 Main Consoles); dubbing studio S (2 Main Consoles); FS con- TV Studio 1, 2, 3 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia trol room AB, Studio E Cologne; Studio B1/2 Bocklemund; dubbing Anhui TV 1000 m² + 1200 m² Studio Hefei-Anhui, China Dusseldorf Germany (2 Main Consoles) studio 1 + 2 BBC Scotland: Studio A & C Glasgow, United Kingdom BR Bayerischer Rundfunk: FM 1, FM 3 (TV); Radio Studio 1 + 2, References: CRESCENDO & NEXUS/NEXUS BR Residenz Munich; FS Studio Franken Nuremberg, Germany STAR Canal 9 Valencia, Spain ASTRO: HD Sport channel, Arena Studio Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia CCTV: Hall 1 + Studio 9 Beijing, China (3 Main Consoles) (2 Main Consoles) Crow TV Studio Tokyo, Japan Anhui TV: 1000 m²- + 1200 m² studio Hefei-Anhui, China (2 Main Deutschlandradio Berlin, Cologne, Germany Consoles) Deutsche Welle TV: Audio-control room 3 Berlin, Germany CCTV: news studios 06 + 07 Beijing, China (7 Main Consoles) FM 802: Radio Osaka, Japan (4 Main Consoles) Hangzhou TV Hangzhou, China (3 Main Consoles) France 2: TV Studio C; News Studio Paris, France HR Hessischer Rundfunk: TV control room 2 Frankfurt/Main; Fuji TV: DAV Studio; Studio A Tokyo, -

Digest of Terrorist Cases

back to navigation page Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Digest of Terrorist Cases United Nations publication Printed in Austria *0986635*V.09-86635—March 2010—500 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Digest of Terrorist Cases UNITED NATIONS New York, 2010 This publication is dedicated to victims of terrorist acts worldwide © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, January 2010. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: UNOV/DM/CMS/EPLS/Electronic Publishing Unit. “Terrorists may exploit vulnerabilities and grievances to breed extremism at the local level, but they can quickly connect with others at the international level. Similarly, the struggle against terrorism requires us to share experiences and best practices at the global level.” “The UN system has a vital contribution to make in all the relevant areas— from promoting the rule of law and effective criminal justice systems to ensuring countries have the means to counter the financing of terrorism; from strengthening capacity to prevent nuclear, biological, chemical, or radiological materials from falling into the -

Historic Centre of Vienna

WHC Nomination Documentation File Name: 1033.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND THE NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Historic Centre of Vienna DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 16th December 2001 STATE PARTY: AUSTRIA CRITERIA: C (ii)(iv)(vi) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 25th Session of the World Heritage Committee The Committee inscribed the Historic Centre of Vienna on the World Heritage List under criteria (ii), (iv), and (vi): Criterion (ii): The urban and architectural qualities of the Historic Centre of Vienna bear outstanding witness to a continuing interchange of values throughout the second millennium. Criterion (iv): Three key periods of European cultural and political development - the Middle Ages, the Baroque period, and the Gründerzeit - are exceptionally well illustrated by the urban and architectural heritage of the Historic Centre of Vienna. Criterion (vi): Since the 16th century Vienna has been universally acknowledged to be the musical capital of Europe. While taking note of the efforts already made for the protection of the historic town of Vienna, the Committee recommended that the State Party undertake the necessary measures to review the height and volume of the proposed new development near the Stadtpark, east of the Ringstrasse, so as not to impair the visual integrity of the historic town. Furthermore, the Committee recommended that special attention be given to continuous monitoring and control of any changes to the morphology of the historic building stock. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Vienna developed from early Celtic and Roman settlements into a Medieval and Baroque city, the capital of the Austro- Hungarian Empire. It played an essential role as a leading European music centre, from the great age of Viennese Classicism through the early part of the 20th century.