Herskovits' Jewishness Kevin A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Beddoe, M.D., Ll.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.S

Obituary JOHN BEDDOE, M.D., LL.D., F.R.C.P., F.R.S. It was oniy m our last volume ^1910, page 359; mat we gave a review of Dr. Beddoe's life as gathered from his own Memories of Eighty Years (Arrowsmith). He is no longer able to write his own biography, but who could write this better than himself in the life-story he has given us ? It becomes our duty to record our appreciation of the work he has done during his eighty-four years, and to express our regret that the record is now closed. He has been called a veteran British anthropo- logist, and as such his reputation is world-wide as an erudite writer and a brilliant authority on all questions of ethnology and anthropology. But it is more particularly as a physician, and his work in the medical field, to which we would now refer. He was Physician to the Bristol Royal Infirmary from 1862 to 1873, when he resigned his office in order that he might have more leisure for his favourite scientific pursuits. For many years he was one of the leading physicians of the district, and it was a cause of great regret to a large circle of medical and other friends and patients when he retired from his work here and made his home at Bradford-on-Avon, where he died on July 19th, his funeral taking place at Edinburgh on July 22nd,. 1911. He held several other medical appointments in Bristol. The Hospital for Sick Women and Children, the Dispensary in Castle Green, and many other institutions claimed him from time to time as physician or consulting physician, and he was. -

Eugenics & Making of Post-Classical Economics

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book Jepson School of Leadership Studies chapters and other publications 2003 Denying Human Homogeneity: Eugenics & Making of Post-Classical Economics Sandra J. Peart University of Richmond, [email protected] David M. Levy Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/jepson-faculty-publications Part of the Behavioral Economics Commons, and the Economic History Commons Recommended Citation Peart, Sandra J., and David M. Levy. "Denying Human Homogeneity: Eugenics & The akM ing of Post-Classical Economics." Journal of the History of Economic Thought 25, no. 03 (2003): 261-88. doi:10.1080/1042771032000114728. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jepson School of Leadership Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book chapters and other publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, Volume 25, Number 3, September 2003 DENYING HUMAN HOMOGENEITY: EUGENICS & THE MAKING OF POST- CLASSICAL ECONOMICS BY SANDRA J. PEART AND DAVID M. LEVY I believe that now and always the conscious selection of the best for reproduction will be impossible; that to propose it is to display a fundamental misunderstand- ing of what individuality implies. The way of nature has always been to slay the hindmost, and there is still no other way, unless we can prevent those who would become the hindmost being born. It is in the sterilization of failures, and not in the selection of successes for breeding, that the possibility of an improvement of the human stock lies. -

The Historiography of Archaeology and Canon Greenwell

The Historiography of Archaeology and Canon Greenwell Tim Murray ([email protected]) In this paper I will focus the bulk of my remarks on setting studies of Canon Greenwell in two broader contexts. The first of these comprises the general issues raised by research into the historiography of archaeology, which I will exemplify through reference to research and writing I have been doing on a new book A History of Prehistoric Archaeology in England, and a new single-volume history of archaeology Milestones in Archaeology, which is due to be completed this year. The second, somewhat narrower context, has to do with situating Greenwell within the discourse of mid-to-late 19th century race theory, an aspect of the history of archaeology that has yet to attract the attention it deserves from archaeologists and historians of anthropology (but see e.g. Morse 2005). Discussing both of these broader contexts will, I hope, help us address and answer questions about the value of the history of archaeology (and of research into the histories of archaeologists), and the links between these histories and a broader project of understanding the changing relationships between archaeology and its cognate disciplines such as anthropology and history. My comments about the historiography of archaeology are in part a reaction to developments that have occurred over the last decade within archaeology, but in larger part a consequence of my own interest in the field. Of course the history of archaeology is not the sole preserve of archaeologists, and it is one of the most encouraging signs that historians of science, and especially historians writing essentially popular works (usually biographies), have paid growing attention to archaeology and its practitioners. -

Flinders Petrie, Race Theory and Biometrics

Challis, D 2016 Skull Triangles: Flinders Petrie, Race Theory and Biometrics. Bulletin of Bofulletin the History of Archaeology, 26(1): 5, pp. 1–8, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bha-556 the History of Archaeology RESEARCH PAPER Skull Triangles: Flinders Petrie, Race Theory and Biometrics Debbie Challis* In 1902 the Egyptian archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie published a graph of triangles indi- cating skull size, shape and ‘racial ability’. In the same year a paper on Naqada crania that had been excavated by Petrie’s team in 1894–5 was published in the anthropometric journal Biometrika, which played an important part in the methodology of cranial measuring in biometrics and helped establish Karl Pearson’s biometric laboratory at University College London. Cicely D. Fawcett’s and Alice Lee’s paper on the variation and correlation of the human skull used the Naqada crania to argue for a controlled system of measurement of skull size and shape to establish homogeneous racial groups, patterns of migration and evolutionary development. Their work was more cautious in tone and judgement than Petrie’s pro- nouncements on the racial origins of the early Egyptians but both the graph and the paper illustrated shared ideas about skull size, shape, statistical analysis and the ability and need to define ‘race’. This paper explores how Petrie shared his archaeological work with a broad number of people and disciplines, including statistics and biometrics, and the context for measuring and analysing skulls at the turn of the twentieth century. The archaeologist William Matthew Flinders Petrie’s The graph vividly illustrates Petrie’s ideas about biologi- belief in biological determinism and racial hierarchy was cal racial difference in a hierarchy that matched brain size informed by earlier ideas and current developments in and skull shape to assumptions about intelligence. -

Intra-European Racism in Nineteenth-Century Anthropology Gustav Jahoda

Intra-European Racism in Nineteenth-Century Anthropology Gustav Jahoda History and Anthropology, Vol. 20, No. 1, March 2009 Nowadays the term “racism” is usually applied in the context of relationships between Europeans and non-European “others”. During the nineteenth century scientific ideas about innate human differences were also applied extensively to various European popula- tions. This was partly due to a category confusion whereby nations came to be regarded as biologically distinct. The origins of “scientific” racism were connected with the use of race as an explanation of history, and with the rise of physiognomy and phrenology. The devel- opment of “craniology” was paralleled and reinforced by ideological writings about “Nordic” racial superiority. In times of conflict such as the Franco-Prussian war, absurd racial theories emerged and social Darwinist anthropologists connected race and class. Such ideas persisted well into the twentieth century and reached their apogee in Nazism. Keywords: Craniology; France; Germany; Nationalism; Race The French Revolution is usually seen as marking the beginnings of modern national- ism, which spread throughout the nineteenth century and became a powerful force; and the ideas of “the nation” or “the national spirit” took on a quasi-mystical tinge (cf. Hayes 1960). The same period saw the rise of anthropology as a scientific discipline, and its practitioners were not immune to the appeal of national sentiment and national pride. At the same time there was a lack of clarity as to what constitutes a nation, which is hardly surprising since there is still no consensus on this issue.1 During the nineteenth century this was generally identified in terms of race2 or “blood” and language. -

Doing Anthropology in Wartime and War Zones

Reinhard Johler, Christian Marchetti, Monique Scheer (eds.) Doing Anthropology in Wartime and War Zones Histoire | Band 12 Reinhard Johler, Christian Marchetti, Monique Scheer (eds.) Doing Anthropology in Wartime and War Zones. World War I and the Cultural Sciences in Europe Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deut- sche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2010 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reprodu- ced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: The Hamburg anthropologist Paul Hambruch with soldiers from (French) Madagascar imprisoned in the camp in Wünsdorf, Germany, in 1918. Source: Wilhelm Doegen (ed.): Unter Fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde. Berlin: Stollberg, 1925, p. 65. Proofread and Typeset by Christel Fraser and Renate Hoffmann Printed by Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-8376-1422-0 Distributed in North America by: Transaction Publishers Tel.: (732) 445-2280 Rutgers University Fax: (732) 445-3138 35 Berrue Circle for orders (U.S. only): Piscataway, NJ 08854 toll free 888-999-6778 Acknowledgments Financial support for the publication of this volume was provided by the Collaborative Research Centre 437: War Experiences – War and Society in Modern Times, University of Tübingen, Germany. Techni- cal support was provided by the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin. -

A Last Contribution to Scottish Ethnology Author(S): John Beddoe Source: the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol

A Last Contribution to Scottish Ethnology Author(s): John Beddoe Source: The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 38 (Jan. - Jun., 1908), pp. 212-220 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2843134 . Accessed: 28/06/2014 15:19 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 91.238.114.35 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 15:19:10 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 212 A LAST CONTRIBUTION TO SCOTTISH ETHNOLOGY. BY JOHN BEDDOE, M.D., LL.D., F.R.S. [WITH PLATE XVIII.] I PROPOs a little considerationof the progress of Scottish Ethnology,before enteringon any criticismof Mr. Gray's valuable paper (Journ.Roy. Anthrpp.Inst., xxxvii,p. 375). Fifty-fiveyears ago, wlhenI broughtout my Contributionto Scottish Ethnology, there were others already engaged in layinigthe foundationsof the subject. -

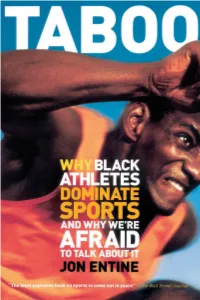

Jon Entine's Taboo

ISBN-13: 978-1-58648-026-4 ISBN-10: 1-58648-026-X PRAISE FOR JON ENTINE'S TABOO "Provocative and informed... A well-intentioned effort for all to come clean on the possibility that black people might just be superior physically, and that there is no negative connection between their physical superiority and their lOs." -John C. Walter, director of the Blacks in Sports Project at the Uni versity of Washington, The Seattle Times "Entine boldly and brilliantly documents numerous physiological differences contributing to black athletic superiority." -Psychology Today "Notable and jarring. It brings intelligence to a little-understood subject." -Business Week "A highly readable blend of science and sports history." -The New York Times Book Review "A powerful history of African-Americans in sports. At long last, someone has the guts to tell it like it is." -St. Petersburg Times "Compelling, bold, comprehensive, informative, enlightening." -Gary Sailes, Associate Professor of Kinesiology, Indiana University and editor of the Journal of the African American Male "Taboo clearly dispenses with the notion that athleticism in Africans or African-Americans is entirely due only to biology or only to culture. Entine understands that as scientists continue to study the complex interactions be tween genes and the environment, population-based genetic differences will continue to surface. Taboo is an excellent survey of a controversial subject." -Human Biology Association President Michael Crawford,University of Kansas professor of Biological Anthropology and Genetics, and former editor of Human Biology "Carefully researched and intellectually honest." -Jay T. Kearney, Former Senior Sports Scientist, United States Olympic Committee "Entine has compiled abundant evidence to support this politically incorrect belief, and it is more than convincing." -The Black World Today "I believe that we need to look at the causes of differences in athletic perfor mance between races as legitimately as we do when we study differences in diseases between the various races. -

Volume 27, Issue 2

History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 27 Issue 2 December 2000 Article 1 January 2000 Volume 27, Issue 2 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation (2000) "Volume 27, Issue 2," History of Anthropology Newsletter: Vol. 27 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol27/iss2/1 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol27/iss2/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. H istoryof A' nthropology N ewsletter XXVII:2 2000 History of Anthropology Newsletter VOLUMEXXVU, NUMBER2 DECEMBER 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOOTNOTES FOR THE HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY Herskovits' Jewishness • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 3 RESEARCH :IN' PROGRESS .•••••••.•••.•• , ••••••••••••••••••••••••••. 9 BmLIOGRAPIDCA ARCANA L History of Twentieth Century Paleoanthropology ••..•••.•..••..• 10 ll. Recent Dissertations • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 16 m. Work by Subscribers ..••...•..•..•.•.••....•.•.•......•.•.. 16 W. Suggested by Our Readers •.......••••.•••...••••••••.•••..•• 17 V. Recent Numbers of Gradhiva •••......••••.....••.•...•••.•..• 21 VI. HistOry of Anthro.pology 9 • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 22 VR Inventario Antropol6gico .••.••.•..•...•••..•.•..•...•.•••... 22 GLEANmGS FROM ACADEMIC GATHERINGS -

Prelims- 1..15

Environment and Ethnicity in India, 1200±1991 Sumit Guha published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011±4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia # Sumit Guha 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Plantin 10/12pt [ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 521 64078 4 hardback Contents `Rama, Sita and Lukshmana in the forest' frontispiece List of maps x List of tables x Acknowledgements xi±xiii Glossary xiv List of abbreviations xv Introduction 1 1 From the archaeology of mind to the archaeology of matter 10 Static societies, changeless races 10 Geology, biology and society in the nineteenth century 11 Indigenous prejudice and colonial knowledge 15 Social segments or living fossils? 21 A historical questioning of the archaeological record 22 2 Subsistence and predation at the margins of cultivation 30 Introduction 30 Nature, culture and landscape in Peninsular India 30 Opportunities and communities 40 The political economy of community interaction -

Colour and Race Author(S): John Beddoe Source: the Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol

Colour and Race Author(s): John Beddoe Source: The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 35 (Jul. - Dec., 1905), pp. 219-250 Published by: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2843064 . Accessed: 14/06/2014 03:00 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 185.44.78.156 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 03:00:32 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ( 219 ) COLOUR AND RACE. The Hquxley Memorial Lectursefor- 1900. BY JOHN BEDDOE, M.D., LL.D., F.R.S. [DELIVERED OCTOBER 31ST, 1905. WITH PLATES XVI, XVII.] THE Huxley lecture is usually said to be commemorativeof the great man whose name it bears. I am not sure that I quite like the adjective. The characterand achievementsof Huxley, the impressionhe made on his countryand his time, are not likely to fade fromour memories. -

THE IDEA of RACE in SCIENCE: GREAT BRITAIN, 1800-1960 St Antony'slmacmillan Series

THE IDEA OF RACE IN SCIENCE: GREAT BRITAIN, 1800-1960 St Antony'slMacmillan Series General editor: Archie Brown, Fellow of St Antony's College, Oxford This series contains academic books written or edited by members of St Antony's College, Oxford, or by authors with a special association with the College, The titles are selected by an editorial board on which both the College and the publishers are represented. S.B. Burman CHIEFDOM POLITICS AND ALIEN LAW Wilhelm Deist THE WEHRMACHT AND GERMAN REARMAMENT Ricardo Ffrench-Davis and Emesto Tironi (editors) LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC ORDER Bohdan Harasymiw POLITICAL ELITE RECRUITMENT IN THE USSR Richard Holt SPORT AND SOCIETY IN MODERN FRANCE Albert Hourani EUROPE AND THE MIDDLE EAST THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST Paul Kennedy and Anthony Nicholls (editors) NATIONALIST AND RACIALIST MOVEMENTS IN BRITAIN AND GERMANY BEFORE 1914 Richard Kindersley (editor) IN SEARCH OF EUROCOMMUNISM GiselaC. Lebzelter POLITICAL ANTI·SEMITISM IN ENGLAND, 1918- 1939 C.A. MacDonald THE UNITED STATES, BRITAIN AND APPEASE MENT, 1936-1939 Pat rick O'Brien (editor) RAILWAYS AND THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF WESTERN EUROPE, 1830-1914 Roger Owen (editor) STUDIES IN THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY OF PALESTINE IN THE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES Irena Powell WRITERS AND SOCIETY IN MODERN JAPAN T.H. Rigby and Ferenc Feher (editors) POLITICAL LEGITIMATION IN COMMUNIST STATES Marilyn Rueschemeyer PROFESSIONAL WORK AND MARRIAGE A.J.R. Russell·Wood THE BLACK MAN IN SLAVERY AND FREEDOM IN COLONIAL BRAZIL David Stafford BRITAIN AND EUROPEAN RESISTANCE, 1940-1945 Nancy Stepan THE IDEA OF RACE IN SCIENCE Guido di Tella ARGENTINA UNDER PERON, 1973-76 Rosemary Thorp and Laurence Whitehead (editors) INFLATION AND STABILISATION IN LATIN AMERICA Rudolf L.