The HOL System DESCRIPTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bit Shifts Bit Operations, Logical Shifts, Arithmetic Shifts, Rotate Shifts

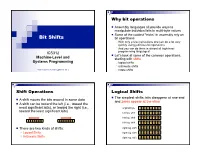

Why bit operations Assembly languages all provide ways to manipulate individual bits in multi-byte values Some of the coolest “tricks” in assembly rely on Bit Shifts bit operations With only a few instructions one can do a lot very quickly using judicious bit operations And you can do them in almost all high-level ICS312 programming languages! Let’s look at some of the common operations, Machine-Level and starting with shifts Systems Programming logical shifts arithmetic shifts Henri Casanova ([email protected]) rotate shifts Shift Operations Logical Shifts The simplest shifts: bits disappear at one end A shift moves the bits around in some data and zeros appear at the other A shift can be toward the left (i.e., toward the most significant bits), or toward the right (i.e., original byte 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 toward the least significant bits) left log. shift 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 left log. shift 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 left log. shift 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 There are two kinds of shifts: right log. shift 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 Logical Shifts right log. shift 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 Arithmetic Shifts right log. shift 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 Logical Shift Instructions Shifts and Numbers Two instructions: shl and shr The common use for shifts: quickly multiply and divide by powers of 2 One specifies by how many bits the data is shifted In decimal, for instance: multiplying 0013 by 10 amounts to doing one left shift to obtain 0130 Either by just passing a constant to the instruction multiplying by 100=102 amounts to doing two left shifts to obtain 1300 Or by using whatever -

Using LLVM for Optimized Lightweight Binary Re-Writing at Runtime

Using LLVM for Optimized Lightweight Binary Re-Writing at Runtime Alexis Engelke, Josef Weidendorfer Department of Informatics Technical University of Munich Munich, Germany EMail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Providing new parallel programming models/ab- helpful in reducing any overhead of provided abstractions. stractions as a set of library functions has the huge advantage But with new languages, porting of existing application that it allows for an relatively easy incremental porting path for code is required, being a high burden for adoption with legacy HPC applications, in contrast to the huge effort needed when novel concepts are only provided in new programming old code bases. Therefore, to provide abstractions such as languages or language extensions. However, performance issues PGAS for legacy codes, APIs implemented as libraries are are to be expected with fine granular usage of library functions. proposed [5], [6]. Libraries have the benefit that they easily In previous work, we argued that binary rewriting can bridge can be composed and can stay small and focused. However, the gap by tightly coupling application and library functions at libraries come with the caveat that fine granular usage of runtime. We showed that runtime specialization at the binary level, starting from a compiled, generic stencil code can help library functions in inner kernels will severely limit compiler in approaching performance of manually written, statically optimizations such as vectorization and thus, may heavily compiled version. reduce performance. In this paper, we analyze the benefits of post-processing the To this end, in previous work [7], we proposed a technique re-written binary code using standard compiler optimizations for lightweight code generation by re-combining existing as provided by LLVM. -

Relational Representation of the LLVM Intermediate Language

NATIONAL AND KAPODISTRIAN UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS SCHOOL OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATICS AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Relational Representation of the LLVM Intermediate Language Eirini I. Psallida Supervisors: Yannis Smaragdakis, Associate Professor NKUA Georgios Balatsouras, PhD Student NKUA ATHENS JANUARY 2014 ΕΘΝΙΚΟ ΚΑΙ ΚΑΠΟΔΙΣΤΡΙΑΚΟ ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ ΑΘΗΝΩΝ ΣΧΟΛΗ ΘΕΤΙΚΩΝ ΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΩΝ ΤΜΗΜΑ ΠΛΗΡΟΦΟΡΙΚΗΣ ΚΑΙ ΤΗΛΕΠΙΚΟΙΝΩΝΙΩΝ ΠΡΟΠΤΥΧΙΑΚΕΣ ΣΠΟΥΔΕΣ ΠΤΥΧΙΑΚΗ ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ Σχεσιακή Αναπαράσταση της Ενδιάμεσης Γλώσσας του LLVM Ειρήνη Ι. Ψαλλίδα Επιβλέποντες: Γιάννης Σμαραγδάκης, Αναπληρωτής Καθηγητής ΕΚΠΑ Γεώργιος Μπαλατσούρας, Διδακτορικός φοιτητής ΕΚΠΑ ΑΘΗΝΑ ΙΑΝΟΥΑΡΙΟΣ 2014 UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Relational Representation of the LLVM Intermediate Language Eirini I. Psallida R.N.: 1115200700272 Supervisor: Yannis Smaragdakis, Associate Professor NKUA Georgios Balatsouras, PhD Student NKUA ΠΤΥΧΙΑΚΗ ΕΡΓΑΣΙΑ Σχεσιακή Αναπαράσταση της ενδιάμεσης γλώσσας του LLVM Ειρήνη Ι. Ψαλλίδα Α.Μ.: 1115200700272 Επιβλέπων: Γιάννης Σμαραγδάκης, Αναπληρωτής Καθηγητής ΕΚΠΑ Γεώργιος Μπαλατσούρας, Διδακτορικός φοιτητής ΕΚΠΑ ΠΕΡΙΛΗΨΗ Περιγράφουμε τη σχεσιακή αναπαράσταση της ενδιάμεσης γλώσσας του LLVM, γνωστή ως LLVM IR. Η υλοποίηση μας παράγει σχέσεις από ένα πρόγραμμα εισόδου σε ενδιάμεση μορφή LLVM. Κάθε σχέση αποθηκεύεται σαν πίνακας βάσης δεδομένων σε ένα περιβάλλον εργασίας Datalog. Αναπαριστούμε το σύστημα τύπων καθώς και το σύνολο εντολών της γλώσσας του LLVM. Υποστηρίζουμε επίσης τους περιορισμούς της γλώσσας προσδιορίζοντάς τους με χρήση της προγραμματιστικής γλώσσας Datalog. ΘΕΜΑΤΙΚΗ ΠΕΡΙΟΧΗ: Μεταγλωτιστές, Γλώσσες Προγραμματισμού ΛΕΞΕΙΣ ΚΛΕΙΔΙΑ: σχεσιακή αναπαράσταση, ενδιάμεση αναπαράσταση, σύστημα τύπων, σύνολο εντολών, LLVM, Datalog ABSTRACT We describe the relational representation of the LLVM intermediate language, known as the LLVM IR. Our implementation produces the relation contents of an input program in the LLVM intermediate form. Each relation is stored as a database table into a Datalog workspace. -

Moscow ML Library Documentation

Moscow ML Library Documentation Version 2.00 of June 2000 Sergei Romanenko, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Claudio Russo, Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom Peter Sestoft, Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Copenhagen, Denmark This document This manual describes the Moscow ML library, which includes parts of the SML Basis Library and several extensions. The manual has been generated automatically from the commented signature files. Alternative formats of this document Hypertext on the World-Wide Web The manual is available at http://www.dina.kvl.dk/~sestoft/mosmllib/ for online browsing. Hypertext in the Moscow ML distribution The manual is available for offline browsing at mosml/doc/mosmllib/index.html in the distribution. On-line help in the Moscow ML interactive system The manual is available also in interactive mosml sessions. Type help "lib"; for an overview of built-in function libraries. Type help "fromstring"; for help on a particular identifier, such as fromString. This will produce a menu of all library structures which contain the identifier fromstring (disregarding the lowercase/uppercase distinction): -------------------------------- | 1 | val Bool.fromString | | 2 | val Char.fromString | | 3 | val Date.fromString | | 4 | val Int.fromString | | 5 | val Path.fromString | | 6 | val Real.fromString | | 7 | val String.fromString | | 8 | val Time.fromString | | 9 | val Word.fromString | | 10 | val Word8.fromString | -------------------------------- Choosing a number from this menu will invoke the -

Bitwise Instructions

Bitwise Instructions CSE 30: Computer Organization and Systems Programming Dept. of Computer Science and Engineering University of California, San Diego Overview vBitwise Instructions vShifts and Rotates vARM Arithmetic Datapath Logical Operators vBasic logical operators: vAND: outputs 1 only if both inputs are 1 vOR: outputs 1 if at least one input is 1 vXOR: outputs 1 if exactly one input is 1 vIn general, can define them to accept >2 inputs, but in the case of ARM assembly, both of these accept exactly 2 inputs and produce 1 output vAgain, rigid syntax, simpler hardware Logical Operators vTruth Table: standard table listing all possible combinations of inputs and resultant output for each vTruth Table for AND, OR and XOR A B A AND B A OR B A XOR B A BIC B 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 Uses for Logical Operators vNote that ANDing a bit with 0 produces a 0 at the output while ANDing a bit with 1 produces the original bit. vThis can be used to create a mask. vExample: 1011 0110 1010 0100 0011 1101 1001 1010 mask: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1111 1111 1111 vThe result of ANDing these: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 1101 1001 1010 mask last 12 bits Uses for Logical Operators vSimilarly, note that ORing a bit with 1 produces a 1 at the output while ORing a bit with 0 produces the original bit. vThis can be used to force certain bits of a string to 1s. -

Bit-Level Transformation and Optimization for Hardware

Bit-Level Transformation and Optimization for Hardware Synthesis of Algorithmic Descriptions Jiyu Zhang*† , Zhiru Zhang+, Sheng Zhou+, Mingxing Tan*, Xianhua Liu*, Xu Cheng*, Jason Cong† *MicroProcessor Research and Development Center, Peking University, Beijing, PRC † Computer Science Department, University Of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA +AutoESL Design Technologies, Los Angeles, CA 90064, USA {zhangjiyu, tanmingxing, liuxianhua, chengxu}@mprc.pku.edu.cn {zhiruz, zhousheng}@autoesl.com, [email protected] ABSTRACT and more popularity [3-6]. However, high-quality As the complexity of integrated circuit systems implementations are difficult to achieve automatically, increases, automated hardware design from higher- especially when the description of the functionality is level abstraction is becoming more and more important. written in a high-level software programming language. However, for many high-level programming languages, For bitwise computation-intensive applications, one of such as C/C++, the description of bitwise access and the main difficulties is the lack of bit-accurate computation is not as direct as hardware description descriptions in high-level software programming languages, and hardware synthesis of algorithmic languages. The wide use of bitwise operations in descriptions may generate sub-optimal implement- certain application domains calls for specific bit-level tations for bitwise computation-intensive applications. transformation and optimization to assist hardware In this paper we introduce a bit-level -

Bitwise Operators

Logical operations ANDORNOTXORAND,OR,NOT,XOR •Loggpical operations are the o perations that have its result as a true or false. • The logical operations can be: • Unary operations that has only one operand (NOT) • ex. NOT operand • Binary operations that has two operands (AND,OR,XOR) • ex. operand 1 AND operand 2 operand 1 OR operand 2 operand 1 XOR operand 2 1 Dr.AbuArqoub Logical operations ANDORNOTXORAND,OR,NOT,XOR • Operands of logical operations can be: - operands that have values true or false - operands that have binary digits 0 or 1. (in this case the operations called bitwise operations). • In computer programming ,a bitwise operation operates on one or two bit patterns or binary numerals at the level of their individual bits. 2 Dr.AbuArqoub Truth tables • The following tables (truth tables ) that shows the result of logical operations that operates on values true, false. x y Z=x AND y x y Z=x OR y F F F F F F F T F F T T T F F T F T T T T T T T x y Z=x XOR y x NOT X F F F F T F T T T F T F T T T F 3 Dr.AbuArqoub Bitwise Operations • In computer programming ,a bitwise operation operates on one or two bit patterns or binary numerals at the level of their individual bits. • Bitwise operators • NOT • The bitwise NOT, or complement, is an unary operation that performs logical negation on each bit, forming the ones' complement of the given binary value. -

Bits, Bytes, and Integers Today: Bits, Bytes, and Integers

Bits, Bytes, and Integers Today: Bits, Bytes, and Integers Representing information as bits Bit-level manipulations Integers . Representation: unsigned and signed . Conversion, casting . Expanding, truncating . Addition, negation, multiplication, shifting . Summary Representations in memory, pointers, strings Everything is bits Each bit is 0 or 1 By encoding/interpreting sets of bits in various ways . Computers determine what to do (instructions) . … and represent and manipulate numbers, sets, strings, etc… Why bits? Electronic Implementation . Easy to store with bistable elements . Reliably transmitted on noisy and inaccurate wires 0 1 0 1.1V 0.9V 0.2V 0.0V For example, can count in binary Base 2 Number Representation . Represent 1521310 as 111011011011012 . Represent 1.2010 as 1.0011001100110011[0011]…2 4 13 . Represent 1.5213 X 10 as 1.11011011011012 X 2 Encoding Byte Values Byte = 8 bits . Binary 000000002 to 111111112 0 0 0000 . Decimal: 010 to 25510 1 1 0001 2 2 0010 . Hexadecimal 0016 to FF16 3 3 0011 . 4 4 0100 Base 16 number representation 5 5 0101 . Use characters ‘0’ to ‘9’ and ‘A’ to ‘F’ 6 6 0110 7 7 0111 . Write FA1D37B16 in C as 8 8 1000 – 0xFA1D37B 9 9 1001 A 10 1010 – 0xfa1d37b B 11 1011 C 12 1100 D 13 1101 E 14 1110 F 15 1111 Example Data Representations C Data Type Typical 32-bit Typical 64-bit x86-64 char 1 1 1 short 2 2 2 int 4 4 4 long 4 8 8 float 4 4 4 double 8 8 8 long double − − 10/16 pointer 4 8 8 Today: Bits, Bytes, and Integers Representing information as bits Bit-level manipulations Integers . -

Episode 7.03 – Coding Bitwise Operations

Episode 7.03 – Coding Bitwise Operations Welcome to the Geek Author series on Computer Organization and Design Fundamentals. I’m David Tarnoff, and in this series, we are working our way through the topics of Computer Organization, Computer Architecture, Digital Design, and Embedded System Design. If you’re interested in the inner workings of a computer, then you’re in the right place. The only background you’ll need for this series is an understanding of integer math, and if possible, a little experience with a programming language such as Java. And one more thing. This episode has direct consequences for our code. You can find coding examples on the episode worksheet, a link to which can be found on the transcript page at intermation.com. Way back in Episode 2.2 – Unsigned Binary Conversion, we introduced three operators that allow us to manipulate integers at the bit level: the logical shift left (represented with two adjacent less-than operators, <<), the arithmetic shift right (represented with two adjacent greater-than operators, >>), and the logical shift right (represented with three adjacent greater-than operators, >>>). These special operators allow us to take all of the bits in a binary integer and move them left or right by a specified number of bit positions. The syntax of all three of these operators is to place the integer we wish to shift on the left side of the operator and the number of bits we wish to shift it by on the right side of the operator. In that episode, we introduced these operators to show how bit shifts could take the place of multiplication or division by powers of two. -

Arithmetic Shift Operations

Computer Science 210 s1c Computer Systems 1 2013 Semester 1 Lecture Notes Lecture 22, 3May13: Real Processors: MIPS, Alpha & the X86 James Goodman! Why am I Talking about the ALPHA? The processor you never heard of 1. It’s real Well, it once was 2. “A design to last 25 years” Introduced in 1992… 3. It’s the best/fastest/cleanest Really! 1-May-13 CS210 658 The MIPS Architecture Millions of Instructions Per Second References Good starting point for the MIPS architecture: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MIPS_architecture ! Very nice summary of architecture ! Lots of pointers to other material Read (more) about the MIPS architecture ! http://www.mrc.uidaho.edu/mrc/people/jff/digital/MIPSir.html • MIPS Instruction reference ! http://www.xs4all.nl/~vhouten/mipsel/r3000-isa.html • Student paper summarizing MIPS Instruction Set ! http://www.langens.eu/tim/ea/mips_en.php • Lots of MIPS documentation: ! http://chortle.ccsu.edu/AssemblyTutorial/TutorialContents.html • Tutorial on MIPS Assembly Language: ! http://www.cs.wisc.edu/~larus/HP_AppA.pdf • Patterson&Hennessy (CS 313 textbook) Appendix A: SPIM, a MIPS simulator (pdf) 1-May-13 CS215s2c 660 The MIPS Computer &*12$ )*+,-.$ "!$ %&$ 3-45*$ !'&($ )/&$ )0&$ &;$ !"#"$%&' ()$*+,"' -"./,0"$,' %:9$ 9"$ /(#$ <4:(,$ %6785$ ;=5>"5>$ &*?@$ 985785$ !"#$ 1-May-13 CS215s2c 661 Registers ! 32 general registers • $0 - $31; also names • $0 is special – when read, gives zero – writing has no effect • $31 sometimes implicit in instruction ! 16/32 floating-point registers • $fgr0-$fgr31 32-bit floating-point registers • Can be configured as 16 64-bit registers ! Special-purpose registers • Hi/Lo (multiplication/division) • Floating-point control/status registers 1-May-13 CS215s2c 662 Pseudoinstructions Some “instructions” are not implemented in the hardware, but are synthesised from two or more real instructions. -

UG902 (V2020.1) May 4, 2021 Revision History

See all versions of this document Vivado Design Suite User Guide High-Level Synthesis UG902 (v2020.1) May 4, 2021 Revision History Revision History The following table shows the revision history for this document. Section Revision Summary 05/04/2021 Version 2020.1 C++ Classes and Templates Removed section detailing support for constructors, destructors, and virtual functions. config_export Updated commands in the Options subsection. config_sdx Updated commands in the Options subsection. UG902 (v2020.1) May 4, 2021Send Feedback www.xilinx.com High-Level Synthesis 2 Table of Contents Revision History...............................................................................................................2 Chapter 1: High-Level Synthesis............................................................................ 5 High-Level Synthesis Benefits....................................................................................................5 High-Level Synthesis Basics....................................................................................................... 6 Understanding Vivado HLS...................................................................................................... 12 Using Vivado HLS...................................................................................................................... 19 Data Types for Efficient Hardware.......................................................................................... 71 Managing Interfaces.................................................................................................................77 -

Design and Implementation of a Tricore Backend for the LLVM Compiler Framework

Design and Implementation of a TriCore Backend for the LLVM Compiler Framework Studienarbeit im Fach Informatik vorgelegt von Christoph Erhardt geboren am 14.11.1984 in Kronach Angefertigt am Department Informatik Lehrstuhl fur¨ Informatik 4 { Verteilte Systeme und Betriebssysteme Friedrich-Alexander-Universit¨at Erlangen-Nurnberg¨ Betreuer: Prof. Dr.-Ing. habil. Wolfgang Schr¨oder-Preikschat Dipl.-Inf. Fabian Scheler Beginn der Arbeit: 01. Dezember 2008 Ende der Arbeit: 01. September 2009 Hiermit versichere ich, dass ich die Arbeit selbstst¨andig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Quellen angefertigt habe und dass die Arbeit in gleicher oder ¨ahnlicher Form noch keiner anderen Prufungsbeh¨ ¨orde vorgelegen hat und von dieser als Teil einer Prufungsleistung¨ angenommen wurde. Alle Stellen, die dem Wortlaut oder dem Sinn nach anderen Werken entnommen sind, habe ich durch Angabe der Quelle als Entlehnung kenntlich gemacht. Erlangen, den 01. September 2009 Uberblick¨ Diese Arbeit beschreibt die Entwicklung und Implementierung eines neuen Backends fur¨ das LLVM-Compiler-Framework, um das Erzeugen von Maschinencode fur¨ die TriCore- Prozessorarchitektur zu erm¨oglichen. Die TriCore-Architektur ist eine fortschrittliche Plattform fur¨ eingebettete Systeme, welche die Merkmale eines Mikrocontrollers, einer RISC-CPU und eines digitalen Signal- prozessors auf sich vereint. Sie findet prim¨ar im Automobilbereich und anderen Echtzeit- systemen Verwendung und wird am Lehrstuhl fur¨ Verteilte Systeme und Betriebssysteme der Universit¨at Erlangen-Nurnberg¨ fur¨ diverse Forschungsprojekte eingesetzt. Bei LLVM handelt es sich um eine moderne Compiler-Infrastruktur, bei deren Ent- wurf besonderer Wert auf Modularit¨at und Erweiterbarkeit gelegt wurde. Aus diesem Grund findet LLVM zunehmend Verbreitung in den verschiedensten Projekten { von Codeanalyse-Werkzeugen uber¨ Just-in-time-Compiler bis hin zu vollst¨andigen Allzweck- Systemcompilern.