Politics Kentucky Style Harry M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

^, ^^Tttism^" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> MAY � 1955 6� J�- W" �,V;Y,�.^4'>^, ^^Tttism^

..%:" -^v �^-*..: J^; SCOTT HALL AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY MAY � 1955 6� j�- w" �,v;y,�.^4'>^, ^^tttiSM^ Pat Gibson (Wisconsin) won her second successive National sen ior Women's skating title this past winter to become first woman in 54 years to turn the trick. Both years she achieved a perfect 150 point total, finishing first in five events. Head cheerleader at U.C.L.A. is Ruth Joos, Gamma Phi Beta. Chosen from 60 appli Allen Missouri Univer cants for the job, Ruth brings Audrey of as Orchid Ball queen of color and spirit to school ac sity reigned Delta Tau Delta. tivities, just as she engenders enthusiasm at the Alpha Iota ri* house. Representing Arizona as her Maid of Cotton in the National contest was Pat Hall of the University of Arizona. Pat was one of five finalists in the national. On campus, she served as freshman class treasurer. \a!!'ss�>-� :--- To climax Gamma Phi Beta week, Idaho State Collet' chapter enjoys annual Toga Dinner. "It's fun," they wr. \ "but three meals a day in this fashion could get prelly, tiresome: Queen of the King Kold Karnival at the University of North Dakota was Karen Sather. Gamma Phi iisters gather around to congratulate Karen (at far left) the night she won the queenship. They are (left to right) Patricia Kent. Falls Church, Va.; Jean Jacobson, Bismarck, N.D.; Mary Kate Whalen, Grand Forks, N.D.; De- lores Paulsen, Bismarck, N.D.; and Marion Day Herzer, Grand Forks, N.D. This Month's Front Cover THE CRESCENT Beautiful Scott Hall, across the quadrangle from the Gamma Phi Beta house, bears the name of former Northwestern Univer of Gamma Phi Beta sity President, Walter Dill Scott. -

Reform and Reaction: Education Policy in Kentucky

Reform and Reaction Education Policy in Kentucky By Timothy Collins Copyright © 2017 By Timothy Collins Permission to download this e-book is granted for educational and nonprofit use only. Quotations shall be made with appropriate citation that includes credit to the author and the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University. Published by the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University in cooperation with Then and Now Media, Bushnell, IL ISBN – 978-0-9977873-0-6 Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs Stipes Hall 518 Western Illinois University 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455-1390 www.iira.org Then and Now Media 976 Washington Blvd. Bushnell IL, 61422 www.thenandnowmedia.com Cover Photos “Colored School” at Anthoston, Henderson County, Kentucky, 1916. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ item/ncl2004004792/PP/ Beechwood School, Kenton County Kentucky, 1896. http://www.rootsweb.ancestry. com/~kykenton/beechwood.school.html Washington Junior High School at Paducah, McCracken County, Kentucky, 1950s. http://www. topix.com/album/detail/paducah-ky/V627EME3GKF94BGN Table of Contents Preface vii Acknowledgements ix 1 Reform and Reaction: Fragmentation and Tarnished 1 Idylls 2 Reform Thwarted: The Trap of Tradition 13 3 Advent for Reform: Moving Toward a Minimum 30 Foundation 4 Reluctant Reform: A.B. ‘Happy” Chandler, 1955-1959 46 5 Dollars for Reform: Bert T. Combs, 1959-1963 55 6 Reform and Reluctant Liberalism: Edward T. Breathitt, 72 1963-1967 7 Reform and Nunn’s Nickle: Louie B. Nunn, 1967-1971 101 8 Child-focused Reform: Wendell H. Ford, 1971-1974 120 9 Reform and Falling Flat: Julian Carroll, 1974-1979 141 10 Silent Reformer: John Y. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950. -

Statement, June 1978

MOREHEAD STATE!NjJ~fl)Jl: People, Programs and Progress at Morehead State Univers ity Vol. 1, N o. 5 M orehead, Ky. 4035 1 June, 1978 To find,get and hold a job It's official name is the "employability skil ls project" Essential ly, the program teaches individuals to use but to the growing number of persons benefiting from various sources of job information, to plan personal and Morehead State University's newest regional service vocational goals, to effectively present themselves to effort, it is the "job course." prospective employers and to develop good work habits. In simple terms, its purpose is to help Kentuckians Since its beginning last fall under a grant from the choose, f ind, get and keep a job of their choice. It is the U.S. Office of Education, the program has enrolled 170 first program of MSU's new Appalachian Development students at 10 locations, including Morehead, Mt. Center and, if the growing demand for the instruction is Sterling, Ashland, Lexington, Louisville and Beattyville. an indication of success, the "job course" is on target. The Lexington and Louisville classes were required by ''Our goal is to help our people be more competitive the funding agency for comparative purposes. in today's job market," said Gary Wilson, project The project utilizes the Adkins Life Skills Program, a coordinator and one of three instructors. "Our clientele series of 10 units of instruction developed by Dr. Win range from high school and college students to senior Adkins of Columbia University. Refined over a citizens but all have determined that they need to seven-year period, the program uses a multi-media improve t heir job-related skills." approach and other teaching techniques. -

(Kentucky) Democratic Party : Political Times of "Miss Lennie" Mclaughlin

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-1981 The Louisville (Kentucky) Democratic Party : political times of "Miss Lennie" McLaughlin. Carolyn Luckett Denning 1943- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Denning, Carolyn Luckett 1943-, "The Louisville (Kentucky) Democratic Party : political times of "Miss Lennie" McLaughlin." (1981). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 333. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/333 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LOUISVILLE (KENTUCKY) DEMOCRATIC PARTY: " POLITICAL TIMES OF "MISS LENNIE" McLAUGHLIN By Carolyn Luckett Denning B.A., Webster College, 1966 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Political Science University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky August 1981 © 1981 CAROLYN LUCKETT DENNING All Rights Reserved THE LOUISVILLE (KENTUCKY) DEMOCRATIC PARTY: POLITICAL TIMES OF "MISS LENNIE" McLAUGHLIN By Carolyn Luckett Denning B.A., Webster College, 1966 A Thesis Approved on <DatM :z 7 I 8 I By the Following Reading Committee Carol Dowell, Thesis Director Joel /Go]tJstein Mary K.:; Tachau Dean Of (j{airman ' ii ABSTRACT This thesis seeks to examine the role of the Democratic Party organization in Louisville, Kentucky and its influence in primary elections during the period 1933 to 1963. -

An AMAZING the Day After Her Graduation

THE MOUNTAIN EAGLE, WHITESBURG, KENTUCKY THURSDAY, MAY 24, 1954 Stauffer, Mrs. Oscar Parks, and Woman's Civic Club of Jenkins Conducts Mrs. A. C. Dittrick. Special guest was Mrs. P. E. Sloan, Annual Installation Of Officers For Club Whitesburg. High prize was pre sented to Mrs. J. M. Stauffer, guest prize to Mrs. P. E. Sloan. LET'S CONTINUE KENTUCKY'S LEADERSHIP In an impressive ceremony, monthly bulletins; Mr. George Mrs. Vernoy Tate, of the Wise, O. Tarleton, Sr., president of T nrrw Tnnnuv .TpnWnc TTiffh I Virginia, Woman's Club, con- Consolidation, who has consist School graduate, Class of '55, IN THE UNITED STATES SENATE ducted the annual installation ently lent a hand to the Club in was initiated into the Kappa Iota of officers service of the Wo- whatever capacity was needed, Epsilon honor society for soph man's Civic Club of Jenkins, and who arranged for addition- at omore men, Eastern State C. Clements man who is and Now it is up to YOU, the people, to decide at the close of a dinner pro- al shelves to be built in the College on May 9th. Require Earle is a Mc-- appre- gram held in the large dining library this year; Mr. Russell ments for this honor are out always has been deeply interested in and ifthis man has the experience, the Donough, work room of The Inn at Wise, Sat- for his faithful standing leadership and responsive to all Kentuckiana. His life is ciation of Kentucky's needs, the character urday night, May 19. and help each year at carnival dedicated to you, people. -

The Public Papers of Governor Lawrence W. Wetherby, 1950-1955

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Legislative and Executive Papers Political Science 12-31-1983 The Public Papers of Governor Lawrence W. Wetherby, 1950-1955 Lawrence W. Wetherby John E. Kleber Morehead State University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Wetherby, Lawrence W. and Kleber, John E., "The Public Papers of Governor Lawrence W. Wetherby, 1950-1955" (1983). Legislative and Executive Papers. 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_science_papers/8 THE PUBLIC PAPERS OF THE GOVERNORS OF KENTUCKY Robert F. Sexton General Editor SPONSORED BY THE Kentucky Advisory Commission on Public Documents AND THE Kentucky Historical Society KENTUCKY ADVISORY COMMISSION ON PUBLIC DOCUMENTS William Buster Henry E. Cheaney Thomas D. Clark, Chairman Leonard Curry Richard Drake Kenneth Harrell Lowell H. Harrison James F. Hopkins Malcolm E. Jewell W. Landis Jones George W. Robinson Robert F. Sexton, General Editor W. Frank Steely Lewis Wallace John D. Wright, Jr. THE PUBLIC PAPERS OF GOVERNOR LAWRENCE W WETHERBY 1950-1955 John E. Kleber, Editor THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Wetherby, Lawrence W. (Lawrence Winchester), 190&- The Public papers of Governor Lawrence W. Wetherby, 1950-1955. (The Public papers of the Governors of Kentucky) Includes index. 1. Kentucky—Politics and government—1951- —Sources. -

Alben W. Barkley: Harry S

Kaleidoscope Volume 7 Article 15 September 2015 Alben W. Barkley: Harry S. Truman’s Unexpected Political Asset John Ghaelian University of Kentucky, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kaleidoscope Part of the History Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Ghaelian, John (2008) "Alben W. Barkley: Harry S. Truman’s Unexpected Political Asset," Kaleidoscope: Vol. 7, Article 15. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kaleidoscope/vol7/iss1/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Office of Undergraduate Research at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kaleidoscope by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AUTHOR John Ghaelian am undergraduate senior majoring in both English and history. The work that I present here was done Alben W. Barkley: I for my senior thesis for my honors history class. By making extensive use of Senator Alben W. Barkley’s Harry S. Truman’s archives located in the M.I. King Special Collections in the library, I was able to explore the role Senator Bar- Unexpected Political kley had on the Democratic presidential ticket in 1948. One of the greatest assets that I had while working Asset on the project was my professor and mentor Dr. Kathi Kern of the history de- partment. Dr. Kern constantly pushed me and the other students in the class to produce better work and probe deeper into our research. -

SENATE-Monday, March 3, 1986

March 3, 1986 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 3389 SENATE-Monday, March 3, 1986 <Legislative day of Monday, February 24, 1986) The Senate met at 12 noon, on the business will not extend beyond the lower dollar would slow the growth of expiration of the recess, and was hour of 1:30 p.m., with Senators per imports. We were told that actions called to order by the President pro mitted to speak therein for not more had been taken to prevent foreign tex tempore [Mr. THURMOND]. than 5 minutes each. tile products from flooding our mar The PRESIDENT pro tempore. The Following routine morning business, kets. Unfortunately, this is not the prayer today will be offered by the the Senate may return to the techni case. Reverend Monsignor John Murphy, cal corrections package to the farm For 2 months in a row, textile im St. Joseph's Church, Washington, DC. bill, or the committee funding resolu ports have increased by over 40 per tion, or possibly the balanced budget PRAYER cent. From September 1985 through amendment. January 1986, imports of textiles were The Reverend Monsignor John The Senate may also turn to the up over 31 percent. The year 1985 Murphy, St. Joseph's Church, Wash consideration of any legislative or ex marked the fifth consecutive year that ington, DC, offered the following ecutive items which have been previ textile and apparel imports have prayer: ously cleared for action. Rollcall votes Heavenly Father, Who art in could occur during the session today. reached new record levels. No wonder Heaven, praised be Your name. -

Lexington, Ky.), 96:55–58 Abraham Lincoln, Contemporary: an Abbey, M

Index A Herman Belz: reviewed, 96:201–3 A&M College (Lexington, Ky.), 96:55–58 Abraham Lincoln, Contemporary: An Abbey, M. E., 93:289 American Legacy, edited by Frank J. Abbot, W. W.: ed., The Papers of George Williams and William D. Pederson: Washington: Confederation Series, Vol. reviewed, 94:182–83 4: April 1786—January 1787, reviewed, Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of 94:183–84 Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Abbott, Augustus H., 97:270 Diplomacy of the Civil War, by Howard Abbott, Dorothy: Thomas D. Clark letter Jones: reviewed, 98:431–32 to, 103:400 Abraham Lincoln and the American Abbott, Edith, 93:32 Political Tradition, edited by John L. Abbott, Grace, 93:32 Thomas: reviewed, 85:181–83 Abbott, H. P. Almon, 90:281 Abraham Lincoln and the Quakers, by Abbott, Richard H.: For Free Press and Daniel Bassuk: noted, 86:99 Equal Rights: Republican Newspapers in Abraham Lincoln and the Second the Reconstruction South, reviewed, American Revolution, by James M. 103:803–5; The Republican Party and McPherson: reviewed, 89:411–12 the South, reviewed, 85:89–91 Abraham Lincoln: A Press Portrait, edited Abercrombie, Mary, 90:252 by Herbert Mitgang: noted, 88:490 Abernathy, Jeff: To Hell and Back: Race Abraham Lincoln: Public Speaker, by and Betrayal in the American Novel, Waldo W. Braden: reviewed, 87:457–58 reviewed, 101:558–60 Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, by Abernathy, Ralph David, 99:29 Allen C. Guelzo: reviewed, 98:429–34 Abernethy, Thomas, 91:299 Abraham Lincoln: Sources and Style of Abiding Faith: A Sesquicentennial History Leadership, edited by Frank J. -

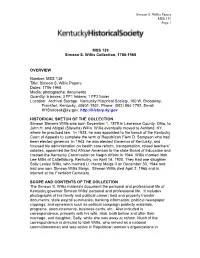

MSS 139 Simeon S. Willis Collection, 1786-1968 OVERVIEW Number

Simeon S. Willis Papers MSS 139 Page 1 MSS 139 Simeon S. Willis Collection, 1786-1968 OVERVIEW Number: MSS 139 Title: Simeon S. Willis Papers Dates: 1786-1968 Media: photographs; documents Quantity: 6 boxes; 3 FF1 folders; 1 FF2 folder Location: Archival Storage. Kentucky Historical Society, 100 W. Broadway, Frankfort, Kentucky, 40601-1931, Phone: (502) 564-1792, Email: [email protected] , http://history.ky.gov HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE COLLECTION Simeon Slavens Willis was born December 1, 1879 in Lawrence County, Ohio, to John H. and Abigail (Slavens) Willis. Willis eventually moved to Ashland, KY, where he practiced law. In 1928, he was appointed to the bench of the Kentucky Court of Appeals to complete the term of Republican Flem D. Sampson who had been elected governor. In 1943, he was elected Governor of Kentucky, and focused his administration on health care reform, transportation, raised teachers' salaries, appointed the first African-American to the state Board of Education and created the Kentucky Commission on Negro Affairs in 1944. Willis married Idah Lee Millis of Catlettsburg, Kentucky, on April 14, 1920. They had one daughter, Sally Lesley Willis, who married Lt. Henry Meigs II on December 30, 1944 and had one son, Simeon Willis Meigs. Simeon Willis died April 2, 1965 and is interred at the Frankfort Cemetery. SCOPE AND CONTENTS OF THE COLLECTION The Simeon S. Willis materials document the personal and professional life of Kentucky governor Simeon Willis' personal and professional life. It includes photographs of his family and political career; land and property transfer documents; state payroll summaries; banking information; political newspaper clippings; and ephemera such as political campaign publicity materials, programs, announcements, business cards, etc. -

Earle C. Clements Interview I

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION The LBJ Library Oral History Collection is composed primarily of interviews conducted for the Library by the University of Texas Oral History Project and the LBJ Library Oral History Project. In addition, some interviews were done for the Library under the auspices of the National Archives and the White House during the Johnson administration. Some of the Library's many oral history transcripts are available on the INTERNET. Individuals whose interviews appear on the INTERNET may have other interviews available on paper at the LBJ Library. Transcripts of oral history interviews may be consulted at the Library or lending copies may be borrowed by writing to the Interlibrary Loan Archivist, LBJ Library, 2313 Red River Street, Austin, Texas, 78705. EARLE C. CLEMENTS ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW I PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, Earle C. Clements Oral History Interview I, 10/24/74, by Michael L. Gillette, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Diskette from the LBJ Library: Transcript, Earle C. Clements Oral History Interview I, 10/24/74, by Michael L. Gillette, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY Legal Agreement Pertaining to the Oral History Interviews of Earle C. Clements In accordance with the provisions of Chapter 21 of Title 44, United States Code and subject to the terms and conditions hereinafter set forth, I, Earle C. Clements of Morganfield, Kentucky do hereby give, donate and convey to the United States of America all my rights, title and interest in the tape recordings and transcripts of the personal interviews conducted on October 24, 1974 and December 6, 1977 in Washington, D.C.