Kentucky Government” Deals with Kentucky’S Governmental Functions and Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

^, ^^Tttism^" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> MAY � 1955 6� J�- W" �,V;Y,�.^4'>^, ^^Tttism^

..%:" -^v �^-*..: J^; SCOTT HALL AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY MAY � 1955 6� j�- w" �,v;y,�.^4'>^, ^^tttiSM^ Pat Gibson (Wisconsin) won her second successive National sen ior Women's skating title this past winter to become first woman in 54 years to turn the trick. Both years she achieved a perfect 150 point total, finishing first in five events. Head cheerleader at U.C.L.A. is Ruth Joos, Gamma Phi Beta. Chosen from 60 appli Allen Missouri Univer cants for the job, Ruth brings Audrey of as Orchid Ball queen of color and spirit to school ac sity reigned Delta Tau Delta. tivities, just as she engenders enthusiasm at the Alpha Iota ri* house. Representing Arizona as her Maid of Cotton in the National contest was Pat Hall of the University of Arizona. Pat was one of five finalists in the national. On campus, she served as freshman class treasurer. \a!!'ss�>-� :--- To climax Gamma Phi Beta week, Idaho State Collet' chapter enjoys annual Toga Dinner. "It's fun," they wr. \ "but three meals a day in this fashion could get prelly, tiresome: Queen of the King Kold Karnival at the University of North Dakota was Karen Sather. Gamma Phi iisters gather around to congratulate Karen (at far left) the night she won the queenship. They are (left to right) Patricia Kent. Falls Church, Va.; Jean Jacobson, Bismarck, N.D.; Mary Kate Whalen, Grand Forks, N.D.; De- lores Paulsen, Bismarck, N.D.; and Marion Day Herzer, Grand Forks, N.D. This Month's Front Cover THE CRESCENT Beautiful Scott Hall, across the quadrangle from the Gamma Phi Beta house, bears the name of former Northwestern Univer of Gamma Phi Beta sity President, Walter Dill Scott. -

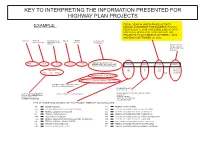

Key to Interpreting the Information Presented for Highway Plan Projects

KEY TO INTERPRETING THE INFORMATION PRESENTED FOR HIGHWAY PLAN PROJECTS FISCAL YEAR IN WHICH PHASE ACTIVITY EXAMPLE: SHOULD COMMENCE. FOR EXAMPLE, FY-2019 BEGINS JULY 1, 2018 AND ENDS JUNE 30, 2019 FOR STATE PROJECTS. FOR. FEDERAL-AID PROJECTS, FY 2019 BEGINS OCTOBER 1, 2018 AND ENDS SEPTEMBER 30, 2019. COUNTY YEAR OF KYTC PROJECT ROUTE LENGTH DESCRIPTION SIX-YEAR PLAN IDENTIFICA TION (MILES) OF PROJECT NUMBER PHASE COST OR TOTAL COST IN SCHEDULED YEAR DOLLARS ADDRESS DEFICIENCIES OF ADAIR 2018 08 - 1068.00 KY-704 0.008 BRIDGE ON KY 704 (11.909) OVER FUNDING PHASE YEAR AMOUNT PETTY'S FORK (001B00078N)(SD) BR D 2019 $175,000 Parent No.: BR C 2020 $490,000 2018 08 - 1068.00 Total $665,000 Milepoints: Fr om: 11.905 T o: 11.913 Purpose and Need: ASSET MANAGEMENT / AM-BRIDGE (P) BEGINNING AND ENDING MILEPOINTS (State Primary Roadway System) STAGE OF PROJECT DEVELOPMENT YEAR OF SIX-YEAR HIGHW AY TYPE OF PRIORITY / TYPE OF WORK P=PRELIMINAR Y ENG./EARLY PUBLIC COORD. PLAN & ITEM NUMBER FROM D=DESIGN WHICH ABOVE ITEM R=RIGHT OF WAY NUMBER WAS DERIVED. U=UTILITY RELOCATION C=CONSTRUCTION TYPE OF FUNDS TO BE UTILIZED FOR THE PROJECT, ABBREVIA TED AS FOLLOWS: BR BRIDGE PROGRAM SAF FEDERAL HIGHWAY SAFETY BR2 JP2 BRAC BOND PROJECTS SECOND PROGRAM SHN FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO HENDERSON CM FEDERAL CONGESTION MITIGATION SLO FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO LOUISVILLE FH FEDERAL FOREST HIGHW AY SLX FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO LEXINGT ON HPP HIGH PRIORITY PROJECTS SNK FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO NORTHERN KENTUCKY KYD FEDERAL DEMONSTRATION FUNDS ALLOCATED TO KENTUCKY SAH FEDERAL STP FUNDS DEDICATED TO ASHLAND NH FEDERAL NATIONAL HIGHW AY SYSTEM SPP STATE CONSTRUCTION HIGH PRIORITY PROJECTS PM PREVENTATIVE MAINTENANCE STP FEDERAL STATEWIDE TRANSPORTATION PROGRAM RRP SAFETY-RAILROAD PROTECTION TE FEDERAL TRANSPORTATION ENHANCEMENT PROGRAM KENTUCKY TRANSPORTATION CABINET Page: 1 SIX YEAR HIGHWAY PLAN 28 JUN 2018 FY - 2018 THRU FY - 2024 COUNTY ITEM NO. -

Kentucky Lawyer, 1993

KENTUCKY UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY COLLEGE OF LAW-1993 APANTHEON OF DEANS: Tom Lewis, Bob Lawson, David Shipley and Bill' Campbell Ci David Shipley becomes Dean of the College of Law he College of Law welcomes David E. fall. His areas of legal expertise are copyright and ad Shipley as its new dean, effective July 1, ministrative law. His most recent publication is a 1993. Dean Shipley comes to us from the casebook, Copyright Law: Cases and Materials, West ~---~ University of Mississippi School of Law, Publishing 1992, with co-authors Howard Abrams of the where he served as Dean and Director of the Law Center University of Detroit School of Law and Sheldon for the last three years. Halpern of Ohio State University. Shipley also has Dean Shipley was raised in Champaign, Illinois, and published two editions of a treatise on administrative was graduated from University High School at the Uni procedure in South Carolina entitled South Carolina versity of Illinois. He received his B.A. degree with Administrative Law. He has taught Civil Procedure, Highest Honors in American History from Oberlin Col- Remedies, Domestic Relations and Intellectual Property lege in 1972, and is as well as Copyright and Administrative Law. In addi a 1975 graduate of tion, he has participated in a wide variety of activities the University of and functions sponsored by the South Carolina and Mis Chicago Law sissippi bars. School, where he Dean Shipley enjoys reading best-selling novels by was Executive authors such as Grisham, Crichton, Turow and Clancy as Editor of the Uni well as history books about the Civil War. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 155 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, JANUARY 12, 2009 No. 6 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Tuesday, January 13, 2009, at 12:30 p.m. Senate MONDAY, JANUARY 12, 2009 The Senate met at 2 p.m. and was The legislative clerk read the fol- was represented in the Senate of the called to order by the Honorable JIM lowing letter: United States by a terrific man and a WEBB, a Senator from the Common- U.S. SENATE, great legislator, Wendell Ford. wealth of Virginia. PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, Senator Ford was known by all as a Washington, DC, January 12, 2009. moderate, deeply respected by both PRAYER To the Senate: sides of the aisle for putting progress The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, ahead of politics. Senator Ford, some of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby fered the following prayer: appoint the Honorable JIM WEBB, a Senator said, was not flashy. He did not seek Let us pray. from the Commonwealth of Virginia, to per- the limelight. He was quietly effective Almighty God, from whom, through form the duties of the Chair. and calmly deliberative. whom, and to whom all things exist, ROBERT C. BYRD, In 1991, Senator Ford was elected by shower Your blessings upon our Sen- President pro tempore. his colleagues to serve as Democratic ators. -

Supplement 1

*^b THE BOOK OF THE STATES .\ • I January, 1949 "'Sto >c THE COUNCIL OF STATE'GOVERNMENTS CHICAGO • ••• • • ••'. •" • • • • • 1 ••• • • I* »• - • • . * • ^ • • • • • • 1 ( • 1* #* t 4 •• -• ', 1 • .1 :.• . -.' . • - •>»»'• • H- • f' ' • • • • J -•» J COPYRIGHT, 1949, BY THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS jk •J . • ) • • • PBir/Tfili i;? THE'UNIfTED STATES OF AMERICA S\ A ' •• • FOREWORD 'he Book of the States, of which this volume is a supplement, is designed rto provide an authoritative source of information on-^state activities, administrations, legislatures, services, problems, and progressi It also reports on work done by the Council of State Governments, the cpm- missions on interstate cooperation, and other agencies concepned with intergovernmental problems. The present suppkinent to the 1948-1949 edition brings up to date, on the basis of information receivjed.from the states by the end of Novem ber, 1948^, the* names of the principal elective administrative officers of the states and of the members of their legislatures. Necessarily, most of the lists of legislators are unofficial, final certification hot having been possible so soon after the election of November 2. In some cases post election contests were pending;. However, every effort for accuracy has been made by state officials who provided the lists aiid by the CouncJLl_ of State Governments. » A second 1949. supplement, to be issued in July, will list appointive administrative officers in all the states, and also their elective officers and legislators, with any revisions of the. present rosters that may be required. ^ Thus the basic, biennial ^oo/t q/7^? States and its two supplements offer comprehensive information on the work of state governments, and current, convenient directories of the men and women who constitute those governments, both in their administrative organizations and in their legislatures. -

Reform and Reaction: Education Policy in Kentucky

Reform and Reaction Education Policy in Kentucky By Timothy Collins Copyright © 2017 By Timothy Collins Permission to download this e-book is granted for educational and nonprofit use only. Quotations shall be made with appropriate citation that includes credit to the author and the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University. Published by the Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs, Western Illinois University in cooperation with Then and Now Media, Bushnell, IL ISBN – 978-0-9977873-0-6 Illinois Institute for Rural Affairs Stipes Hall 518 Western Illinois University 1 University Circle Macomb, IL 61455-1390 www.iira.org Then and Now Media 976 Washington Blvd. Bushnell IL, 61422 www.thenandnowmedia.com Cover Photos “Colored School” at Anthoston, Henderson County, Kentucky, 1916. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/ item/ncl2004004792/PP/ Beechwood School, Kenton County Kentucky, 1896. http://www.rootsweb.ancestry. com/~kykenton/beechwood.school.html Washington Junior High School at Paducah, McCracken County, Kentucky, 1950s. http://www. topix.com/album/detail/paducah-ky/V627EME3GKF94BGN Table of Contents Preface vii Acknowledgements ix 1 Reform and Reaction: Fragmentation and Tarnished 1 Idylls 2 Reform Thwarted: The Trap of Tradition 13 3 Advent for Reform: Moving Toward a Minimum 30 Foundation 4 Reluctant Reform: A.B. ‘Happy” Chandler, 1955-1959 46 5 Dollars for Reform: Bert T. Combs, 1959-1963 55 6 Reform and Reluctant Liberalism: Edward T. Breathitt, 72 1963-1967 7 Reform and Nunn’s Nickle: Louie B. Nunn, 1967-1971 101 8 Child-focused Reform: Wendell H. Ford, 1971-1974 120 9 Reform and Falling Flat: Julian Carroll, 1974-1979 141 10 Silent Reformer: John Y. -

True Conservative Or Enemy of the Base?

Paul Ryan: True Conservative or Enemy of the Base? An analysis of the Relationship between the Tea Party and the GOP Elmar Frederik van Holten (s0951269) Master Thesis: North American Studies Supervisor: Dr. E.F. van de Bilt Word Count: 53.529 September January 31, 2017. 1 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Page intentionally left blank 2 You created this PDF from an application that is not licensed to print to novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Table of Content Table of Content ………………………………………………………………………... p. 3 List of Abbreviations……………………………………………………………………. p. 5 Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………..... p. 6 Chapter 2: The Rise of the Conservative Movement……………………….. p. 16 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 16 Ayn Rand, William F. Buckley and Barry Goldwater: The Reinvention of Conservatism…………………………………………….... p. 17 Nixon and the Silent Majority………………………………………………….. p. 21 Reagan’s Conservative Coalition………………………………………………. p. 22 Post-Reagan Reaganism: The Presidency of George H.W. Bush……………. p. 25 Clinton and the Gingrich Revolutionaries…………………………………….. p. 28 Chapter 3: The Early Years of a Rising Star..................................................... p. 34 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 34 A Moderate District Electing a True Conservative…………………………… p. 35 Ryan’s First Year in Congress…………………………………………………. p. 38 The Rise of Compassionate Conservatism…………………………………….. p. 41 Domestic Politics under a Foreign Policy Administration……………………. p. 45 The Conservative Dream of a Tax Code Overhaul…………………………… p. 46 Privatizing Entitlements: The Fight over Welfare Reform…………………... p. 52 Leaving Office…………………………………………………………………… p. 57 Chapter 4: Understanding the Tea Party……………………………………… p. 58 Introduction……………………………………………………………………… p. 58 A three legged movement: Grassroots Tea Party organizations……………... p. 59 The Movement’s Deep Story…………………………………………………… p. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300a (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM Historic Resources of Ashland CONTINUATION SHEET ITEM NUMBER 8_____PAGE 3______________________ BATH AVENUE HISTORIC DISTRICT Statement of Significance Since the inception of the Kentucky Iron, Coal and Manufacturing Company's plan for Ashland, western Bath Avenue has been considered to be the city's most prestigious residential neighborhood. The first two houses on the street were built in 1855-56 by Hugh and John Means, prominent Ohio iron industrialists who moved to Ashland in conjunction with the Kentucky Iron, Coal and Manufacturing Company. Through the early twentieth century, property on the street was essentially reserved for local industry owners and managers who were related by family or business connections. Multiple lots continued to be held by families, and only one or two houses occupied each block in 1877, according to the Titus, Simmons Atlas map of Ashland. As a result of the slow development of the street, the neighborhood is now characterized by a diversity of architectural styles that is not seen elsewhere in Ashland. Although the neighborhood previously extended for six blocks along Bath Avenue, large-scale commercial development in the 1200 block has severed the western end of the street, and reduced the length of the coherent neighborhood to four blocks. Therefore the National Register boundary has not been extended beyond 13th Street. Form No. 10-300a (Hev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM Historic Resources of Ashland CONTI NU ATION SHEET_________________ITEM NUMBER 8 PAGE 4________________ BATH AVENUE HISTORIC DISTRICT Description The Bath Avenue Historic District includes four blocks of Bath Avenue between ,13th and 17th Streets. -

Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Political History History 1987 Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963 John Ed Pearce Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Pearce, John Ed, "Divide and Dissent: Kentucky Politics, 1930-1963" (1987). Political History. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_political_history/3 Divide and Dissent This page intentionally left blank DIVIDE AND DISSENT KENTUCKY POLITICS 1930-1963 JOHN ED PEARCE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1987 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2006 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Qffices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pearce,John Ed. Divide and dissent. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Kentucky-Politics and government-1865-1950. -

Principal State and Territorial Officers

/ 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Atlorneys .... State Governors Lieulenanl Governors General . Secretaries of State. Alabama. James E. Foisoin J.C.Inzer .A. .A.. Carniichael Sibyl Pool Arizona Dan E. Garvey None Fred O. Wilson Wesley Boiin . Arkansas. Sid McMath Nathan Gordon Ike Marry . C. G. Hall California...... Earl Warren Goodwin J. Knight • Fred N. Howser Frank M. Jordan Colorado........ Lee Knous Walter W. Jolinson John W. Metzger George J. Baker Connecticut... Chester Bowles Wm. T. Carroll William L. Hadden Mrs. Winifred McDonald Delaware...:.. Elbert N. Carvel A. duPont Bayard .Mbert W. James Harris B. McDowell, Jr. Florida.. Fuller Warren None Richard W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia Herman Talmadge Marvin Griffin Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. * Idaho ;C. A. Robins D. S. Whitehead Robert E. Sniylie J.D.Price IlUnola. .-\dlai E. Stevenson Sher^vood Dixon Ivan.A. Elliott Edward J. Barrett Indiana Henry F. Schricker John A. Walkins J. Etnmett McManamon Charles F. Fleiiiing Iowa Wm. S.'Beardsley K.A.Evans Robert L. Larson Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas Frank Carlson Frank L. Hagainan Harold R. Fatzer (a) Larry Ryan Kentucky Earle C. Clements Lawrence Wetherby A. E. Funk • George Glenn Hatcher Louisiana Earl K. Long William J. Dodd Bolivar E. Kemp Wade O. Martin. Jr. Maine.. Frederick G. Pgynp None Ralph W. Farris Harold I. Goss Maryland...... Wm. Preston Lane, Jr. None Hall Hammond Vivian V. Simpson Massachusetts. Paul A. Dever C. F. Jeff Sullivan Francis E. Kelly Edward J. Croiiin Michigan G. Mennen Williams John W. Connolly Stephen J. Roth F. M. Alger, Jr.- Minnesota. -

Hell No, We Won't Go

RIPON SEPTEMBER, 1971 VOL. VII, No. 11 ONE DOLLAR THE LINDSAY SWITCH Hell No, We Won't Go ALSO THIS MONTH: • A Preview of the 1972 Senate Races • A Guide to the Democrats -Partll Clifford Brown • The GOP McGovern Commission • The Learned Man's RaRerty John McClaughry THE RIPON SOCIETY INC is ~ Republican research and SUMMARY OF CONTENTS I • policy organization whose members are young business, academic and professional men and women. It has national headquarters In Cambridge, Massachusetts, THE LINDSAY SWITCH chapters in thirteen cities, National Associate members throughout the fifty states, and several affiliated groups of subchapter status. The Society is supported by chapter dues, individual contribu A reprint of the Ripon Society's statement at a news tions and revenues from its publications and contract work. The conference the day following John Lindsay's registration SOciety offers the following options for annual contribution: Con as a Democrat. As we've said before, Ripon would rather trtbutor $25 or more; Sustainer $100 or more; Founder $1000 or fight than switch. -S more. Inquiries about membership and chapter organization should be addressed to the National Executive Director. NATIONAL GOVERNING BOARD Officers 'Howard F. Gillette, Jr., President 'Josiah Lee Auspitz, Chairman 01 the Executive Committee 'lioward L. Reiter, Vice President EDITORIAL POINTS "Robert L. Beal. Treasurer Ripon advises President Nixon that he can safely 'R. Quincy White, Jr., Secretary Boston Philadelphia ignore the recent conservative "suspension of support." 'Martha Reardon 'Richard R. Block Also Ripon urges reform of the delegate selection process Martin A. LInsky Rohert J. Moss for the '72 national convention. -

Statement, June 1978

MOREHEAD STATE!NjJ~fl)Jl: People, Programs and Progress at Morehead State Univers ity Vol. 1, N o. 5 M orehead, Ky. 4035 1 June, 1978 To find,get and hold a job It's official name is the "employability skil ls project" Essential ly, the program teaches individuals to use but to the growing number of persons benefiting from various sources of job information, to plan personal and Morehead State University's newest regional service vocational goals, to effectively present themselves to effort, it is the "job course." prospective employers and to develop good work habits. In simple terms, its purpose is to help Kentuckians Since its beginning last fall under a grant from the choose, f ind, get and keep a job of their choice. It is the U.S. Office of Education, the program has enrolled 170 first program of MSU's new Appalachian Development students at 10 locations, including Morehead, Mt. Center and, if the growing demand for the instruction is Sterling, Ashland, Lexington, Louisville and Beattyville. an indication of success, the "job course" is on target. The Lexington and Louisville classes were required by ''Our goal is to help our people be more competitive the funding agency for comparative purposes. in today's job market," said Gary Wilson, project The project utilizes the Adkins Life Skills Program, a coordinator and one of three instructors. "Our clientele series of 10 units of instruction developed by Dr. Win range from high school and college students to senior Adkins of Columbia University. Refined over a citizens but all have determined that they need to seven-year period, the program uses a multi-media improve t heir job-related skills." approach and other teaching techniques.