Introduction to Middle High German: a Reader and Grammar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Automatic Part-Of-Speech Tagger for Middle Low German

An automatic part-of-speech tagger for Middle Low German Mariya Koleva, Melissa Farasyn, Bart Desmet, Anne Breitbarth and Véronique Hoste Ghent University Syntactically annotated corpora are highly important for enabling large-scale diachronic and diatopic language research. Such corpora have recently been developed for a variety of historical languages, or are still under development. One of those under development is the fully tagged and parsed Corpus of Historical Low German (CHLG), which is aimed at facilitating research into the highly under-researched diachronic syntax of Low German. The present paper reports on a crucial step in creating the corpus, viz. the creation of a part-of-speech tagger for Middle Low German (MLG). Having been transmitted in several non-standardised written varieties, MLG poses a challenge to standard POS taggers, which usually rely on normalized spelling. We outline the major issues faced in the creation of the tagger and present our solutions to them. Keywords: historical linguistics, part-of-speech tagging, conditional random fields, feature selection, normalization 1. Introduction Corpora of historical texts annotated with different levels of grammatical information, such as parts of speech, (inflectional) morphology, syntactic chunks, clausal syntax, provide an important resource for studies of diachronic syntactic variation and change (e.g. Kroch et al. 2000, Rögnvaldsson & Helgadóttir 2011). They enable the automatic extraction of syntactic information from historical texts (more than is manually possible), and allow making statistically valid observations. Apart from reducing the amount of time required for data retrieval, an important advantage is that they make research testable and replicable. The Corpus of Historical Low German (CHLG) (Breitbarth et al. -

An Independent Assessment of the Sinking of the MV DERBYSHIRE

SNAME Transactions, Vol. 106, 1998, pp. 59-103 An Independent Assessment of the Sinking of the MV DERBYSHIRE Douglas Faulkner, Fellow, Emeritus Professor of Naval Architecture, University of Glasgow, Scotland The author was appointed by the UK Department of Tranq~ort as a fellow Assessor with R.A. Williams during Lord Donaldson's Assessment (1995) of the loss of the OBO ship DERBYSHIRE and throughout the planning and conduct of the two final surveys of the wreck. This paper is drawn from the independ- ent report (b~udknel; 1998a) and may be considered complementary to those of the UK and EC Asses- sors (Williams and Torchio, 1998a and 1998b). The paper deals with the history and loss of the ship, in- cluding the concept developed in 1995 of 13 possible loss scenarios in a Jormal safety Risk Matrix" of probability and seriousness. It analyses abnormal wave effects on hatch cover collapse, on ship bending, and on flooding of bow spaces and no. 1 hold. The implosion-explosion mechanics during sinking is out- lined to explain the devastation of the wreck. The 1996 and 1997 underwater surveys are outlined as are the findings of.fact. Each of the final 14 loss scenarios is analysed in the light of the firm and circum- stantial survey evidence, plus many other factotw of service experience, analyses and experiments. The updated Risk Matrix speaks for itself and leads to the prime conclusions and major recommendations. Nomenclature ~ Register, 1987) which also depicts the oil fuel, fresh water and minimal ballast water distribution. Her estimated displacement as she approached Japan was about A = 194,000 te and hence 1. -

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo-European and Germanic Background Indo-European Background It has already been mentioned in this course that German and English are related languages. Two languages can be related to each other in much the same way that two people can be related to each other. If two people share a common ancestor, say their mother or their great-grandfather, then they are genetically related. Similarly, German and English are genetically related because they share a common ancestor, a language which was spoken in what is now northern Germany sometime before the Angles and the Saxons migrated to England. We do not have written records of this language, unfortunately, but we have a good idea of what it must have looked and sounded like. We have arrived at our conclusions as to what it looked and sounded like by comparing the sounds of words and morphemes in earlier written stages of English and German (and Dutch) and in modern-day English and German dialects. As a result of the comparisons we are able to reconstruct what the original language, called a proto-language, must have been like. This particular proto-language is usually referred to as Proto-West Germanic. The method of reconstruction based on comparison is called the comparative method. If faced with two languages the comparative method can tell us one of three things: 1) the two languages are related in that both are descended from a common ancestor, e.g. German and English, 2) the two are related in that one is the ancestor of the other, e.g. -

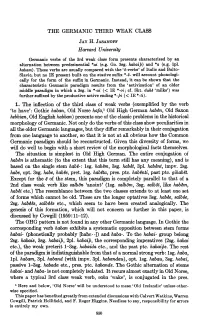

The Germanic Third Weak Class

THE GERMANIC THIRD WEAK CLASS JAY H. JASANOFF Harvard University Germanic verbs of the 3rd weak class form presents characterized by an alternation between predesinential *ai (e.g. Go. 3sg. habai1» and *a (e.g. Ipl. habam). These verbs are usually compared with the 'e-verbs' of Italic and Balto Slavic, but no IE present built on the stative suffix *-e- will account phonologi cally for the form of the suffix in Germanic. Instead, it can be shown that the characteristic Germanic paradigm results from the 'activization' of an older middle paradigm in which a 3sg. in *-ai « IE *-oi; cf. Skt. duh~ 'milks') was further suffixed by the productive active ending *-Pi « IE *-ti). 1. The inflection of the third class of weak verbs (exemplified by the verb 'to have': Gothic haban, Old Norse hafa,! Old High German hab~, Old Saxon hebbian, Old English habban) presents one of the classic problems in the historical morphology of Germanic. Not only do the verbs of this class show peculiarities in all the older Germanic languages, but they differ remarkably in their conjugation from one language to another, so that it is not at all obvious how the Common Germanic paradigm should be reconstructed. Given this diversity of forms, we will do well to begin with a short review of the morphological facts themselves. The situation is simplest in Old High German. The entire conjugation of hab~n is athematic (to the extent that this term still has any meaning), and is based on the single stem hab~-: 1sg. hab~, 3sg. hab~t, 3pl. -

Teaching English-Spanish Cognates Using the Texas 2X2 Picture Book Reading Lists

TEACHING ENGLISH-SPANISH COGNATES USING THE TEXAS 2X2 PICTURE BOOK READING LISTS JOSÉ A. MONTELONGO, ANITA C. HERNÁNDEZ, & ROBERTA J. HERTER ABSTRACT English-Spanish cognates are words that possess identical or nearly identical spellings and meanings in both English and Spanish as a result of being derived mainly from Latin and Greek. Of major importance is the fact that many of the more than 20,000 cognates in English are academic vocabulary words, terms essential for comprehending school texts. The Texas 2x2 Reading List is a list of recommended reading books for children ranging in ages from pre-school to the early primary grades. The list is published yearly by the Children’s Round Table, a division of the Texas Library Association. The books that comprise the Texas 2x2 Reading List are a rich source of vocabulary and contain many English-Spanish cognates. Teachers can use the Texas 2x2 picture books to create a cognate vocabulary lesson that can be taught as a companion to a picture book read- aloud. The purpose of this paper is to present some of the different types of cognate vocabulary lessons that may be created to accompany a picture book read-aloud. The lessons are based on the morphological and spelling regularities between English and Spanish cognates and can be used to teach students how to convert words from one language to another. Examples of the different types of regularities and the Texas 2x2 books that contain them are included, as is an example cognate vocabulary lesson plan to accompany the picture book, Oddrey (Whamond, 2012). -

A Penn-Style Treebank of Middle Low German

A Penn-style Treebank of Middle Low German Hannah Booth Joint work with Anne Breitbarth, Aaron Ecay & Melissa Farasyn Ghent University 12th December, 2019 1 / 47 Context I Diachronic parsed corpora now exist for a range of languages: I English (Taylor et al., 2003; Kroch & Taylor, 2000) I Icelandic (Wallenberg et al., 2011) I French (Martineau et al., 2010) I Portuguese (Galves et al., 2017) I Irish (Lash, 2014) I Have greatly enhanced our understanding of syntactic change: I Quantitative studies of syntactic phenomena over time I Findings which have a strong empirical basis and are (somewhat) reproducible 2 / 47 Context I Corpus of Historical Low German (‘CHLG’) I Anne Breitbarth (Gent) I Sheila Watts (Cambridge) I George Walkden (Konstanz) I Parsed corpus spanning: I Old Low German/Old Saxon (c.800-1050) I Middle Low German (c.1250-1600) I OLG component already available: HeliPaD (Walkden, 2016) I 46,067 words I Heliand text I MLG component currently under development 3 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I MLG = West Germanic scribal dialects in Northern Germany and North-Eastern Netherlands 4 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I The rise and fall of (written) Low German I Pre-800: pre-historical I c.800-1050: Old Low German/Old Saxon I c.1050-1250 Attestation gap (Latin) I c.1250-1370: Early MLG I c.1370-1520: ‘Classical MLG’ (Golden Age) I c.1520-1850: transition to HG as in written domain I c.1850-today: transition to HG in spoken domain 5 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I Hanseatic League: alliance between North German towns and trade outposts abroad to promote economic and diplomatic interests (13th-15th centuries) 6 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I LG served as lingua franca for supraregional communication I High prestige across North Sea and Baltic regions I Associated with trade and economic prosperity I Linguistic legacy I Huge amounts of linguistic borrowings in e.g. -

Old Frisian, an Introduction To

An Introduction to Old Frisian An Introduction to Old Frisian History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. University of Leiden John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremmer, Rolf H. (Rolf Hendrik), 1950- An introduction to Old Frisian : history, grammar, reader, glossary / Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Frisian language--To 1500--Grammar. 2. Frisian language--To 1500--History. 3. Frisian language--To 1550--Texts. I. Title. PF1421.B74 2009 439’.2--dc22 2008045390 isbn 978 90 272 3255 7 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 3256 4 (Pb; alk. paper) © 2009 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Table of contents Preface ix chapter i History: The when, where and what of Old Frisian 1 The Frisians. A short history (§§1–8); Texts and manuscripts (§§9–14); Language (§§15–18); The scope of Old Frisian studies (§§19–21) chapter ii Phonology: The sounds of Old Frisian 21 A. Introductory remarks (§§22–27): Spelling and pronunciation (§§22–23); Axioms and method (§§24–25); West Germanic vowel inventory (§26); A common West Germanic sound-change: gemination (§27) B. -

Yiddish and Relation to the German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 6-30-2016 Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects Bryan Witmore University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Witmore, B.(2016). Yiddish and Relation To The German Dialects. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ etd/3522 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YIDDISH AND ITS RELATION TO THE GERMAN DIALECTS by Bryan Witmore Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in German College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2016 Accepted by: Kurt Goblirsch, Director of Thesis Lara Ducate, Reader Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Bryan Witmore, 2016 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis project was made possible in large part by the German program at the University of South Carolina. The technical assistance that propelled this project was contributed by the staff at the Ted Mimms Foreign Language Learning Center. My family was decisive in keeping me physically functional and emotionally buoyant through the writing process. Many thanks to you all. iii ABSTRACT In an attempt to balance the complex, multi-component nature of Yiddish with its more homogenous speech community – Ashekenazic Jews –Yiddishists have proposed definitions for the Yiddish language that cannot be considered linguistic in nature. -

"Deor" Legends

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1969 The "Deor" Legends: Their Dissemination in Germanic Literature Doris Larraine Mabry Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Mabry, Doris Larraine, "The "Deor" Legends: Their Dissemination in Germanic Literature" (1969). Masters Theses. 4078. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4078 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #3 To: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. Subject: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is rece1v1ng a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements. Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. ' \ Date Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because Date Author /LB1861.CS7XM1126>C2/ THE ".!BOB" 1 00-BHllS1 THBJ:B DJ:SSIHDATXOK IRG'IRMAUCIrrmATUR8 (TITLE) BY D9rla Larraine �bry THESIS SUBMlmD IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Kastertt Arta IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1969 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE ADVISER DEPARTMENT HEAD "D•or" S.• an Old ln&llah P•. -

Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, German, Middle German, East Middle German

1 ALEMANA GERMAN, ALEMÁN, ALLEMAND Language family: Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, German, Middle German, East Middle German. Language codes: ISO 639-1 de ISO 639-2 ger (ISO 639-2/B) deu (ISO 639-2/T) ISO 639-3 Variously: deu – Standard German gmh – Middle High german goh – Old High German gct – Aleman Coloniero bar – Austro-Bavarian cim – Cimbrian geh – Hutterite German kksh – Kölsch nds – Low German sli – Lower Silesian ltz – Luxembourgish vmf – Main-Franconian mhn – Mócheno pfl – Palatinate German pdc – Pennsylvania German pdt – Plautdietsch swg – Swabian German gsw – Swiss German uln – Unserdeutssch sxu – Upper Saxon wae – Walser German wep – Westphalian Glotolog: high1287. Linguasphere: [show] 2 Beste izen batzuk (autoglotonimoa: Deutsch). deutsch alt german, standard [GER]. german, standard [GER] hizk. Alemania; baita AEB, Arabiar Emirerri Batuak, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgika, Bolivia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Brasil, Danimarka, Ekuador, Errumania, Errusia (Europa), Eslovakia, Eslovenia, Estonia, Filipinak, Finlandia, Frantzia, Hegoafrika, Hungaria, Italia, Kanada, Kazakhstan, Kirgizistan, Liechtenstein, Luxenburgo, Moldavia, Namibia, Paraguai, Polonia, Puerto Rico, Suitza, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Txekiar Errepublika, Txile, Ukraina eta Uruguain ere. Dialektoa: erzgebirgisch. Hizkuntza eskualde erlazionatuenak dira Bavarian, Schwäbisch, Allemannisch, Mainfränkisch, Hessisch, Palatinian, Rheinfränkisch, Westfälisch, Saxonian, Thuringian, Brandenburgisch eta Low saxon. Aldaera asko ez dira ulerkorrak beren artean. -

Vowel Change in English and German: a Comparative Analysis

Vowel change in English and German: a comparative analysis Miriam Calvo Fernández Degree in English Studies Academic Year: 2017/2018 Supervisor: Reinhard Bruno Stempel Department of English and German Philology and Translation Abstract English and German descend from the same parent language: West-Germanic, from which other languages, such as Dutch, Afrikaans, Flemish, or Frisian come as well. These would, therefore, be called “sister” languages, since they share a number of features in syntax, morphology or phonology, among others. The history of English and German as sister languages dates back to the Late antiquity, when they were dialects of a Proto-West-Germanic language. After their split, more than 1,400 years ago, they developed their own language systems, which were almost identical at their earlier stages. However, this is not the case anymore, as can be seen in their current vowel systems: the German vowel system is composed of 23 monophthongs and 8 diphthongs, while that of English has only 12 monophthongs and 8 diphthongs. The present paper analyses how the English and German vowels have gradually changed over time in an attempt to understand the differences and similarities found in their current vowel systems. In order to do so, I explain in detail the previous stages through which both English and German went, giving special attention to the vowel changes from a phonological perspective. Not only do I describe such processes, but I also contrast the paths both languages took, which is key to understand all the differences and similarities present in modern English and German. The analysis shows that one of the main reasons for the differences between modern German and English is to be found in all the languages English has come into contact with in the course of its history, which have exerted a significant influence on its vowel system, making it simpler than that of German. -

A Middle High German Primer, with Grammar, Notes, and Glossary

> 1053 MIDDLE HIGH GERMAN PRIMER WITH GRAMMAR, NOTES, AND GLOSSARY BY JOSEPH WRIGHT M.A., PH.D., D.C.L., LL.D., L1TT.D. FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY CORPUS CHRISTI PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE PHILOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD THIRD EDITION RE-WRITTEN AND ENLARGED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1917 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE BOMBAY HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY pr EXTRACTS FROM THE PREFACES TO THE FIRST AND SECOND EDITIONS THE present book has been written in the hope that it will serve as an elementary introduction to the larger German works on the subject from which I have appro- priated whatever seemed necessary for the purpose. In the grammar much aid has been derived from Paul's Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik, second edition, Halle, 1884, and Weinhold's Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik, second edition, Paderborn, 1883. The former work, besides con- taining by far the most complete syntax, is also the only Middle High German Grammar which is based on the present state of German Philology. ... I believe that the day is not far distant when English students will take a much more lively interest in the study of their own and the other Germanic languages (especially German and Old Norse) than has hitherto been the case. And if this little book should contribute anything towards furthering the cause, it will have amply fulfilled its purpose. LONDON : January, 1888. WHEN I wrote the preface to the first edition of this primer in 1888, I ventured to predict that the interest of English students in the subject would grow and develop as time went on, but I hardly expected that it would grow so much that a second edition of the book would be required within iv Preface to the Second Edition so short a period.