An Automatic Part-Of-Speech Tagger for Middle Low German

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The German Civil Code

TUE A ERICANI LAW REGISTER FOUNDED 1852. UNIERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA DEPART=ENT OF LAW VOL. {4 0 - S'I DECEMBER, 1902. No. 12. THE GERMAN CIVIL CODE. (Das Biirgerliche Gesetzbuch.) SOURCES-PREPARATION-ADOPTION. The magnitude of an attempt to codify the German civil. laws can be adequately appreciated only by remembering that for more than fifteefn centuries central Europe was the world's arena for startling political changes radically involv- ing territorial boundaries and of necessity affecting private as well as public law. With no thought of presenting new data, but that the reader may properly marshall events for an accurate compre- hension of the irregular development of the law into the modem and concrete results, it is necessary to call attention to some of the political- and social factors which have been potent and conspicuous since the eighth century. Notwithstanding the boast of Charles the Great that he was both master of Europe and the chosen pr6pagandist of Christianity and despite his efforts in urging general accept- ance of the Roman law, which the Latinized Celts of the western and southern parts of his titular domain had orig- THE GERM AN CIVIL CODE. inally been forced to receive and later had willingly retained, upon none of those three points did the facts sustain his van- ity. He was constrained to recognize that beyond the Rhine there were great tribes, anciently nomadic, but for some cen- turies become agricultural when not engaged in their normal and chief occupation, war, who were by no means under his control. His missii or special commissioners to those people were not well received and his laws were not much respected. -

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN History of the German Language 1 Indo-European and Germanic Background Indo-European Background It has already been mentioned in this course that German and English are related languages. Two languages can be related to each other in much the same way that two people can be related to each other. If two people share a common ancestor, say their mother or their great-grandfather, then they are genetically related. Similarly, German and English are genetically related because they share a common ancestor, a language which was spoken in what is now northern Germany sometime before the Angles and the Saxons migrated to England. We do not have written records of this language, unfortunately, but we have a good idea of what it must have looked and sounded like. We have arrived at our conclusions as to what it looked and sounded like by comparing the sounds of words and morphemes in earlier written stages of English and German (and Dutch) and in modern-day English and German dialects. As a result of the comparisons we are able to reconstruct what the original language, called a proto-language, must have been like. This particular proto-language is usually referred to as Proto-West Germanic. The method of reconstruction based on comparison is called the comparative method. If faced with two languages the comparative method can tell us one of three things: 1) the two languages are related in that both are descended from a common ancestor, e.g. German and English, 2) the two are related in that one is the ancestor of the other, e.g. -

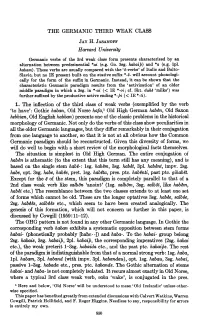

The Germanic Third Weak Class

THE GERMANIC THIRD WEAK CLASS JAY H. JASANOFF Harvard University Germanic verbs of the 3rd weak class form presents characterized by an alternation between predesinential *ai (e.g. Go. 3sg. habai1» and *a (e.g. Ipl. habam). These verbs are usually compared with the 'e-verbs' of Italic and Balto Slavic, but no IE present built on the stative suffix *-e- will account phonologi cally for the form of the suffix in Germanic. Instead, it can be shown that the characteristic Germanic paradigm results from the 'activization' of an older middle paradigm in which a 3sg. in *-ai « IE *-oi; cf. Skt. duh~ 'milks') was further suffixed by the productive active ending *-Pi « IE *-ti). 1. The inflection of the third class of weak verbs (exemplified by the verb 'to have': Gothic haban, Old Norse hafa,! Old High German hab~, Old Saxon hebbian, Old English habban) presents one of the classic problems in the historical morphology of Germanic. Not only do the verbs of this class show peculiarities in all the older Germanic languages, but they differ remarkably in their conjugation from one language to another, so that it is not at all obvious how the Common Germanic paradigm should be reconstructed. Given this diversity of forms, we will do well to begin with a short review of the morphological facts themselves. The situation is simplest in Old High German. The entire conjugation of hab~n is athematic (to the extent that this term still has any meaning), and is based on the single stem hab~-: 1sg. hab~, 3sg. hab~t, 3pl. -

Teaching English-Spanish Cognates Using the Texas 2X2 Picture Book Reading Lists

TEACHING ENGLISH-SPANISH COGNATES USING THE TEXAS 2X2 PICTURE BOOK READING LISTS JOSÉ A. MONTELONGO, ANITA C. HERNÁNDEZ, & ROBERTA J. HERTER ABSTRACT English-Spanish cognates are words that possess identical or nearly identical spellings and meanings in both English and Spanish as a result of being derived mainly from Latin and Greek. Of major importance is the fact that many of the more than 20,000 cognates in English are academic vocabulary words, terms essential for comprehending school texts. The Texas 2x2 Reading List is a list of recommended reading books for children ranging in ages from pre-school to the early primary grades. The list is published yearly by the Children’s Round Table, a division of the Texas Library Association. The books that comprise the Texas 2x2 Reading List are a rich source of vocabulary and contain many English-Spanish cognates. Teachers can use the Texas 2x2 picture books to create a cognate vocabulary lesson that can be taught as a companion to a picture book read- aloud. The purpose of this paper is to present some of the different types of cognate vocabulary lessons that may be created to accompany a picture book read-aloud. The lessons are based on the morphological and spelling regularities between English and Spanish cognates and can be used to teach students how to convert words from one language to another. Examples of the different types of regularities and the Texas 2x2 books that contain them are included, as is an example cognate vocabulary lesson plan to accompany the picture book, Oddrey (Whamond, 2012). -

A Penn-Style Treebank of Middle Low German

A Penn-style Treebank of Middle Low German Hannah Booth Joint work with Anne Breitbarth, Aaron Ecay & Melissa Farasyn Ghent University 12th December, 2019 1 / 47 Context I Diachronic parsed corpora now exist for a range of languages: I English (Taylor et al., 2003; Kroch & Taylor, 2000) I Icelandic (Wallenberg et al., 2011) I French (Martineau et al., 2010) I Portuguese (Galves et al., 2017) I Irish (Lash, 2014) I Have greatly enhanced our understanding of syntactic change: I Quantitative studies of syntactic phenomena over time I Findings which have a strong empirical basis and are (somewhat) reproducible 2 / 47 Context I Corpus of Historical Low German (‘CHLG’) I Anne Breitbarth (Gent) I Sheila Watts (Cambridge) I George Walkden (Konstanz) I Parsed corpus spanning: I Old Low German/Old Saxon (c.800-1050) I Middle Low German (c.1250-1600) I OLG component already available: HeliPaD (Walkden, 2016) I 46,067 words I Heliand text I MLG component currently under development 3 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I MLG = West Germanic scribal dialects in Northern Germany and North-Eastern Netherlands 4 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I The rise and fall of (written) Low German I Pre-800: pre-historical I c.800-1050: Old Low German/Old Saxon I c.1050-1250 Attestation gap (Latin) I c.1250-1370: Early MLG I c.1370-1520: ‘Classical MLG’ (Golden Age) I c.1520-1850: transition to HG as in written domain I c.1850-today: transition to HG in spoken domain 5 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I Hanseatic League: alliance between North German towns and trade outposts abroad to promote economic and diplomatic interests (13th-15th centuries) 6 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I LG served as lingua franca for supraregional communication I High prestige across North Sea and Baltic regions I Associated with trade and economic prosperity I Linguistic legacy I Huge amounts of linguistic borrowings in e.g. -

Old Frisian, an Introduction To

An Introduction to Old Frisian An Introduction to Old Frisian History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. University of Leiden John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremmer, Rolf H. (Rolf Hendrik), 1950- An introduction to Old Frisian : history, grammar, reader, glossary / Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Frisian language--To 1500--Grammar. 2. Frisian language--To 1500--History. 3. Frisian language--To 1550--Texts. I. Title. PF1421.B74 2009 439’.2--dc22 2008045390 isbn 978 90 272 3255 7 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 3256 4 (Pb; alk. paper) © 2009 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Table of contents Preface ix chapter i History: The when, where and what of Old Frisian 1 The Frisians. A short history (§§1–8); Texts and manuscripts (§§9–14); Language (§§15–18); The scope of Old Frisian studies (§§19–21) chapter ii Phonology: The sounds of Old Frisian 21 A. Introductory remarks (§§22–27): Spelling and pronunciation (§§22–23); Axioms and method (§§24–25); West Germanic vowel inventory (§26); A common West Germanic sound-change: gemination (§27) B. -

Rechtsgeschichte Legal History

Zeitschri des Max-Planck-Instituts für europäische Rechtsgeschichte Rechts R Journal of the Max Planck Institute for European Legal History geschichte g Rechtsgeschichte Legal History www.rg.mpg.de http://www.rg-rechtsgeschichte.de/rg22 Rg 22 2014 79 – 89 Zitiervorschlag: Rechtsgeschichte – Legal History Rg 22 (2014) http://dx.doi.org/10.12946/rg22/079-089 Heiner Lück Aspects of the transfer of the Saxon-Magdeburg Law to Central and Eastern Europe Dieser Beitrag steht unter einer Creative Commons cc-by-nc-nd 3.0 Abstract An important impetus forthedevelopmentand dissemination of the Saxon Mirror, the most famous and influential German law book of Central Ger- many between 1220 and 1235 by one Eike von Repgow, was the municipal law of the town of Magdeburg, the so called Magdeburg Law.Itisone of the most important German town laws of the Middle Ages. In conjunction with the Saxon Mirror with which it was closely interconnected, the Magdeburg Law reached the territories of Silesia, Poland, the lands belonging to the Teutonic Order, the Baltic countries (especially Lithuania), Uk- raine, Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia and Hungary. The peculiar symbiosis between Saxon Mirror and Magdeburg Law on the way to Eastern Europe has been expressed in the source texts (ius Teutonicum, ius Maideburgense and ius Saxonum in the early originally carried the same content). Ius Maidebur- gense (Magdeburg Law) has reached the foremost position as a broad term, which encompassed the Saxon territorial law as well as the Magdeburg town law, and, quite frequently, also the German Law (ius Teutonicum) in general. Modern scholar- ship recognizes this terminological overlapping and interrelatedness through the notion of Saxon- Magdeburg Law. -

![The Holy Roman Empire [1873]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7391/the-holy-roman-empire-1873-1457391.webp)

The Holy Roman Empire [1873]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Viscount James Bryce, The Holy Roman Empire [1873] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

A Middle High German Primer, with Grammar, Notes, and Glossary

> 1053 MIDDLE HIGH GERMAN PRIMER WITH GRAMMAR, NOTES, AND GLOSSARY BY JOSEPH WRIGHT M.A., PH.D., D.C.L., LL.D., L1TT.D. FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY CORPUS CHRISTI PROFESSOR OF COMPARATIVE PHILOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD THIRD EDITION RE-WRITTEN AND ENLARGED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1917 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE BOMBAY HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY pr EXTRACTS FROM THE PREFACES TO THE FIRST AND SECOND EDITIONS THE present book has been written in the hope that it will serve as an elementary introduction to the larger German works on the subject from which I have appro- priated whatever seemed necessary for the purpose. In the grammar much aid has been derived from Paul's Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik, second edition, Halle, 1884, and Weinhold's Mittelhochdeutsche Grammatik, second edition, Paderborn, 1883. The former work, besides con- taining by far the most complete syntax, is also the only Middle High German Grammar which is based on the present state of German Philology. ... I believe that the day is not far distant when English students will take a much more lively interest in the study of their own and the other Germanic languages (especially German and Old Norse) than has hitherto been the case. And if this little book should contribute anything towards furthering the cause, it will have amply fulfilled its purpose. LONDON : January, 1888. WHEN I wrote the preface to the first edition of this primer in 1888, I ventured to predict that the interest of English students in the subject would grow and develop as time went on, but I hardly expected that it would grow so much that a second edition of the book would be required within iv Preface to the Second Edition so short a period. -

Schwabenspiegel: Lehenrechtbuch; an English Translation

RICE UNIVERSITY S CHWABENSPIEGSL: LSHEKR2CHTBUCK AH MODISH TRANSLATION by William John Slayton A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FOLB’ILLrLElTi’ OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Thesis Director's signature: Houston, Texas May, 1967 Abstract SCHWA33HSPIEGSL: LBHEHHSCHTBUCH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION ’William John Slayton This English translation of the Lehenrechtbuch (Book of Territorial IJ3.IT) of the thirteenth century Schwabenspiegel (Swabian Mirror), a German lawbook written in Middle High German, has two basic objects. The immediate goal of the translator was to work with the Middle High German text as a philological problem, the solution of which is a rendering of the text into an English version which attempts to express as literally as possible the German sense of the words, yet preserve the spirit in which the Schwabenspiegel was composed. The second goal., the more signifi¬ cant of the two, is to present for the first time to English readers with an interest in medieval law the text of a legal document which was previously accessible only to those who could read Middle High German, The translation procedure was as follows: The main text upon which the translation is based, the edition of F. L, A, von Lassberg (Dor Schwabenspie gel [Neudruck der Ausgabe l81*o\ Oleisenhelin/Glan, 196l3), was supplemented by the translator in places where it seemed garbled, incom¬ plete, or otherwise in error, by making reference to an edition by K, A, Eckhardt (Schwabenspiegel Kuraform [Gdttingen, l°60-6l3). This translator, knows of no other extant translations of the Schwabenspiegel in English, modern German, or any other language, and therefore a comparison of this translation with another one to clarify obscure passages was out of the question, The translator did, however, lean heavily upon the various histories of German law listed in the bibliography. -

Manuscripts and Printed Texts of the Silesian-Małopolska Compilation

Chapter 1 Manuscripts and Printed Texts of the Silesian-Małopolska Compilation 1 Sources and Contents of the Weichbild This project begins with a closer look at the sources of the Magdeburg Weichbild. As we know it to be a compilation, the first step will be to mark out its components. In general, it is possible to distinguish two major branches of the Weichbild, the vulgate used in Eastern Germany and a version prepared for users in the Kingdom of Poland. Traditionally, the latter has been referred to as Konrad of Opole’s compilation. In this study, however, I will refer to it as the Silesian-Małopolska compilation, in order to make a clear distinction between that source and Weichbild’s Polish branch as a whole, which, as I will argue, does not rely exclusively on Konrad of Opole’s autograph. 1.1 Konrad of Opole’s Compilation or the Silesian-Małopolska Compilation: A Question of Terminology Although this study deals primarily with the Latin Weichbild, it would be unwise to ignore the corresponding German sources. This raises the prob- lem of terminology, that is, naming the compilation which comprises all of the manuscripts of that group. Most scholars believe that the compilation is the work of Konrad of Opole.1 However, the text in the Cracow manuscript (BJ 169), attributed to Konrad of Opole, cannot be the archetype of the com- pilation. This is proven by the fact that some passages (provisions) of the Henryków MS (II F 8), also of Silesian provenance, are slightly closer to the 1 Ernst Th. -

Download: Brill.Com/Brill-Typeface

History of Wills, Testators and Their Families in Late Medieval Krakow Later Medieval Europe Managing Editor Douglas Biggs (University of Nebraska – Kearney) Editorial Board Sara M. Butler (The Ohio State University) Kelly DeVries (Loyola University Maryland) William Chester Jordan (Princeton University) Cynthia J. Neville (Dalhousie University) Kathryn L. Reyerson (University of Minnesota) volume 23 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/lme History of Wills, Testators and Their Families in Late Medieval Krakow Tools of Power By Jakub Wysmułek leiden | boston This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. The translation and Open Access publication of the book was supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education. The book received a financial grant (21H 17 0288 85) in the frame of National Programme for the Development of Humanities - 6 Round. Cover illustration: The Payment of the Tithes (The Tax-Collector), also known as Village Lawyer, Pieter Breughel the Younger. LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012442 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012443 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”.