Online Companion to a Historical Phonology of English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some English Words Illustrating the Great Vowel Shift. Ca. 1400 Ca. 1500 Ca. 1600 Present 'Bite' Bi:Tə Bəit Bəit

Some English words illustrating the Great Vowel Shift. ca. 1400 ca. 1500 ca. 1600 present ‘bite’ bi:tә bәit bәit baIt ‘beet’ be:t bi:t bi:t bi:t ‘beat’ bɛ:tә be:t be:t ~ bi:t bi:t ‘abate’ aba:tә aba:t > abɛ:t әbe:t әbeIt ‘boat’ bɔ:t bo:t bo:t boUt ‘boot’ bo:t bu:t bu:t bu:t ‘about’ abu:tә abәut әbәut әbaUt Note that, while Chaucer’s pronunciation of the long vowels was quite different from ours, Shakespeare’s pronunciation was similar enough to ours that with a little practice we would probably understand his plays even in the original pronuncia- tion—at least no worse than we do in our own pronunciation! This was mostly an unconditioned change; almost all the words that appear to have es- caped it either no longer had long vowels at the time the change occurred or else entered the language later. However, there was one restriction: /u:/ was not diphthongized when followed immedi- ately by a labial consonant. The original pronunciation of the vowel survives without change in coop, cooper, droop, loop, stoop, troop, and tomb; in room it survives in the speech of some, while others have shortened the vowel to /U/; the vowel has been shortened and unrounded in sup, dove (the bird), shove, crumb, plum, scum, and thumb. This multiple split of long u-vowels is the most signifi- cant IRregularity in the phonological development of English; see the handout on Modern English sound changes for further discussion. -

Case Closed, Vol. 27 Ebook Free Download

CASE CLOSED, VOL. 27 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 29 Oct 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421516790 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed, Vol. 27 PDF Book January 20, [22] Ai Haibara. Views Read Edit View history. Until Jimmy can find a cure for his miniature malady, he takes on the pseudonym Conan Edogawa and continues to solve all the cases that come his way. The Junior Detective League and Dr. Retrieved November 13, January 17, [8]. Product Details. They must solve the mystery of the manor before they are all killed off or kill each other. They talk about how Shinichi's absence has been filled with Dr. Chicago 7. April 10, [18] Rachel calls Richard to get involved. Rachel thinks it could be the ghost of the woman's clock tower mechanic who died four years prior. Conan's deductions impress Jodie who looks at him with great interest. Categories : Case Closed chapter lists. And they could have thought Shimizu was proposing a cigarette to Bito. An unknown person steals the police's investigation records relating to Richard Moore, and Conan is worried it could be the Black Organization. The Junior Detectives find the missing boy and reconstruct the diary pages revealing the kidnapping motive and what happened to the kidnapper. The Junior Detectives meet an elderly man who seems to have a lot on his schedule, but is actually planning on committing suicide. Magic Kaito Episodes. Anime News Network. Later, a kid who is known to be an obsessive liar tells the Detective Boys his home has been invaded but is taken away by his parents. -

The English Language

The English Language Version 5.0 Eala ðu lareow, tæce me sum ðing. [Aelfric, Grammar] Prof. Dr. Russell Block University of Applied Sciences - München Department 13 – General Studies Winter Semester 2008 © 2008 by Russell Block Um eine gute Note in der Klausur zu erzielen genügt es nicht, dieses Skript zu lesen. Sie müssen auch die “Show” sehen! Dieses Skript ist der Entwurf eines Buches: The English Language – A Guide for Inquisitive Students. Nur der Stoff, der in der Vorlesung behandelt wird, ist prüfungsrelevant. Unit 1: Language as a system ................................................8 1 Introduction ...................................... ...................8 2 A simple example of structure ..................... ......................8 Unit 2: The English sound system ...........................................10 3 Introduction..................................... ...................10 4 Standard dialects ................................ ....................10 5 The major differences between German and English . ......................10 5.1 The consonants ................................. ..............10 5.2 Overview of the English consonants . ..................10 5.3 Tense vs. lax .................................. ...............11 5.4 The final devoicing rule ....................... .................12 5.5 The “th”-sounds ................................ ..............12 5.6 The “sh”-sound .................................. ............. 12 5.7 The voiced sounds / Z/ and / dZ / ...................................12 5.8 The -

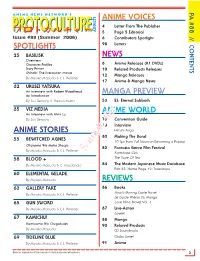

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

ETH-2 Requests to Examine Seis.Pub

Request to Examine Statements of Economic Interests Your name Telephone number Email Address Street address City State Zip code I am making this request solely on my own behalf, independent of any other individual or organizaon. OR I am making this request on behalf of the individual or organizaon below. Requested on behalf of the following Individual or organizaon Telephone number Street address City State Zip code Year(s) Filed Name of individuals whose State‐ State agency or office held, or Format Requested (Each SEI covers the ment are requested posion sought previous calendar year) Electronic Printed Connue on the next page and aach addional pages as needed. W. S. §§ 19.48(8) and 19.55(1) require the Ethics Commission to obtain the above informaon and to nofy each offi‐ cial or candidate of the identy of a person examining the filer’s Statement of Economic Interests. I understand that use of a ficous name or address or failure to idenfy the person on whose behalf the request is made is a violaƟon of law. I un‐ derstand that any person who intenonally violates this subchapter is subject to a fine of up to $5,000 and imprisonment for up to one year. W. S. § 19.58(1). In accordance with W. S. § 15.04(1)(m), the Wisconsin Ethics Commission states that no personally idenfiable informaon is likely to be used for purposes other than those for which it is collected. ¥Ý: Statements are $0.15 per printed page (statements are at least four pages, plus any applicable aachments), and elec‐ tronic copies are $0.07 per PDF file. -

Laryngeal Features in German* Michael Jessen Bundeskriminalamt, Wiesbaden Catherine Ringen University of Iowa

Phonology 19 (2002) 189–218. f 2002 Cambridge University Press DOI: 10.1017/S0952675702004311 Printed in the United Kingdom Laryngeal features in German* Michael Jessen Bundeskriminalamt, Wiesbaden Catherine Ringen University of Iowa It is well known that initially and when preceded by a word that ends with a voiceless sound, German so-called ‘voiced’ stops are usually voiceless, that intervocalically both voiced and voiceless stops occur and that syllable-final (obstruent) stops are voiceless. Such a distribution is consistent with an analysis in which the contrast is one of [voice] and syllable-final stops are devoiced. It is also consistent with the view that in German the contrast is between stops that are [spread glottis] and those that are not. On such a view, the intervocalic voiced stops arise because of passive voicing of the non-[spread glottis] stops. The purpose of this paper is to present experimental results that support the view that German has underlying [spread glottis] stops, not [voice] stops. 1 Introduction In spite of the fact that voiced (obstruent) stops in German (and many other Germanic languages) are markedly different from voiced stops in languages like Spanish, Russian and Hungarian, all of these languages are usually claimed to have stops that contrast in voicing. For example, Wurzel (1970), Rubach (1990), Hall (1993) and Wiese (1996) assume that German has underlying voiced stops in their different accounts of Ger- man syllable-final devoicing in various rule-based frameworks. Similarly, Lombardi (1999) assumes that German has underlying voiced obstruents in her optimality-theoretic (OT) account of syllable-final laryngeal neutralisation and assimilation in obstruent clusters. -

Open House Demonstrates Garrison FD Capabilities

Vol. 48, No. 8, June 2019 Serving the Greater Stuttgart Military Community www.stuttgartcitizen.com Patch Elementary School student Cadence Sherwood, age 7, takes her fi rst ride into the sky on a ladder truck. “It wasn’t at all scary. I think it Garrison fi refi ghters attack a car fi re in a dramatic demonstration. was really good. I could see all of the buildings.” Open house demonstrates garrison FD capabilities Story and photos by John Reese is was just one of the many USAG Stuttgart Public A airs scenes at the USAG FD open house. Included were numerous static dis- Black smoke billowed from plays of re ghting apparatus of a fully engulfed car re, ladder the garrison and supporting re trucks reached skyward and sirens departments from Boeblingen and howled as the re ghters of USAG Leonberg. e German auto club Stuttgart Fire Department raced to ADAC had a life-sized driving simu- the Panzer Exchange parking lot, lator, and the emergency/disaster re- May 18. A large crowd gathered near lief agency THW brought displays of the entrance of the Exchange, react- their equipment and a bouncy house ing to the many explosive pops and for the kids. Some of the events were crackles the car made in its death focused on teaching moments for throes. e intense heat was felt community children, with toy re 20-30 yards from the four-wheeled helmets and a visit by re safety mas- Austin Bail, 22 months old, checks out the driver’s seat of an immaculate inferno until the re ghters aked cot Sparky. -

Birdsong in the Music of Olivier Messiaen a Thesis Submitted To

P Birdsongin the Music of Olivier Messiaen A thesissubmitted to MiddlesexUniversity in partial fulfilment of the requirementsfor the degreeof Doctor of Philosophy David Kraft School of Art, Design and Performing Arts Nfiddlesex University December2000 Abstract 7be intentionof this investigationis to formulatea chronologicalsurvey of Messiaen'streatment of birdsong,taking into accountthe speciesinvolved and the composer'sevolving methods of motivic manipulation,instrumentation, incorporation of intrinsic characteristicsand structure.The approachtaken in this studyis to surveyselected works in turn, developingappropriate tabular formswith regardto Messiaen'suse of 'style oiseau',identified bird vocalisationsand eventhe frequentappearances of musicthat includesfamiliar characteristicsof bird style, althoughnot so labelledin the score.Due to the repetitivenature of so manymotivic fragmentsin birdsong,it has becomenecessary to developnew terminology and incorporatederivations from other research findings.7be 'motivic classification'tables, for instance,present the essentialmotivic featuresin somevery complexbirdsong. The studybegins by establishingthe importanceof the uniquemusical procedures developed by Messiaen:these involve, for example,questions of form, melodyand rhythm.7he problemof is 'authenticity' - that is, the degreeof accuracywith which Messiaenchooses to treat birdsong- then examined.A chronologicalsurvey of Messiaen'suse of birdsongin selectedmajor works follows, demonstratingan evolutionfrom the ge-eralterm 'oiseau' to the preciseattribution -

Chapter ETH 26

Published under s. 35.93, Wis. Stats., by the Legislative Reference Bureau. 19 ETHICS COMMISSION ETH 26.02 Chapter ETH 26 SETTLEMENT OFFER SCHEDULE ETH 26.01 Definitions. ETH 26.03 Settlement of lobbying violations. ETH 26.02 Settlement of campaign finance violations. ETH 26.04 Settlement of ethics violations. ETH 26.01 Definitions. In this chapter: (15) “Preelection campaign finance report” includes the cam- (1) “15 day report” means the report referred to in s. 13.67, paign finance reports referred to in ss. 11.0204 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) Stats. (b), and (5) (a), 11.0304 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), 11.0404 (1m) “Business day” means any day Monday to Friday, (2) (b) and (3) (a), 11.0504 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), excluding Wisconsin legal holidays as defined in s. 995.20, Stats. 11.0604 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), 11.0804 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), and 11.0904 (2) (b), (3) (a), (4) (b), and (5) (a), (2) “Commission” means the Wisconsin Ethics Commission. Stats., that are due no earlier than 14 days and no later than 8 days (3) “Continuing report” includes the campaign finance before an election. reports due in January and July referred to in ss. 11.0204 (2) (c), (16) “Preprimary campaign finance report” includes the cam- (3) (b), (4) (c) and (d), (5) (b) and (c), and (6) (a) and (b), 11.0304 paign finance reports referred to in ss. 11.0204 (2) (a) and (4) (a), (2) (c), (3) (b), (4) (c) and (d), and (5) (b) and (c), 11.0404 (2) (c) 11.0304 (2) (a) and (4) (a), 11.0404 (2) (a), 11.0504 (2) (a) and (4) and (d) and (3) (b) and (c), 11.0504 (2) (c), (3) (b), (4) (c) and (d), (a), 11.0604 (2) (a) and (4) (a), 11.0804 (2) (a) and (4) (a), and and (5) (b) and (c), 11.0604 (2) (c), (3) (b), (4) (c) and (d), and (5) 11.0904 (2) (a) and (4) (a), Stats., that are due no earlier than 14 (b) and (c), 11.0704 (2), (3) (a), (4) (a) and (b), and (5) (a) and (b), days and no later than 8 days before a primary. -

F472aab6-Ca7c-43D1-Bb92-38Be9e2b83da.Pdf

NR TITEL ARTIEST 1 Hotel California Eagles 2 Bohemian Rhapsody Queen 3 Dancing Queen Abba 4 Stayin' Alive Bee Gees 5 You're The First, The Last, My Everything Barry White 6 Child In Time Deep Purple 7 Paradise By The Dashboard Light Meat Loaf 8 Go Your Own Way Fleetwood Mac 9 Stairway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 10 Sultans Of Swing Dire Straits 11 Piano Man Billy Joel 12 Heroes David Bowie 13 Roxanne Police 14 Let It Be Beatles 15 Music John Miles 16 I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor 17 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 18 Nutbush City Limits Ike & Tina Turner 19 No Woman No Cry Bob Marley & The Wailers 20 We Will Rock You Queen 21 Baker Street Gerry Rafferty 22 Angie Rolling Stones 23 Whole Lotta Rosie AC/DC 24 I Was Made For Loving You Kiss 25 Another Brick In The Wall Pink Floyd 26 Radar Love Golden Earring 27 You're The One That I Want John Travolta & Olivia Newton-John 28 Wuthering Heights Kate Bush 29 Born To Be Alive Patrick Hernandez 30 Imagine John Lennon 31 Your Song Elton John 32 Denis Blondie 33 Mr. Blue Sky Electric Light Orchestra 34 Lola Kinks 35 Don't Stop Me Now Queen 36 Dreadlock Holiday 10CC 37 Meisjes Raymond Van Het Groenewoud 38 That's The Way I Like It KC & The Sunshine Band 39 Love Hurts Nazareth 40 Black Betty Ram Jam 41 Down Down Status Quo 42 Riders On The Storm Doors 43 Paranoid Black Sabbath 44 Highway To Hell AC/DC 45 Y.M.C.A. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

Famous People from Czech Republic

2018 R MEMPHIS IN MAY INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL Tennessee Academic Standards 2018 EDUCATION CURRICULUM GUIDE MEMPHIS IN MAY INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL Celebrates the Czech Republic in 2018 Celebrating the Czech Republic is the year-long focus of the 2018 Memphis in May International Festival. The Czech Republic is the twelfth European country to be honored in the festival’s history, and its selection by Memphis in May International Festival coincides with their celebration of 100 years as an independent nation, beginning as Czechoslovakia in 1918. The Czech Republic is a nation with 10 million inhabitants, situated in the middle of Europe, with Germany, Austria, Slovakia and Poland as its neighbors. Known for its rich historical and cultural heritage, more than a thousand years of Czech history has produced over 2,000 castles, chateaux, and fortresses. The country resonates with beautiful landscapes, including a chain of mountains on the border, deep forests, refreshing lakes, as well as architectural and urban masterpieces. Its capital city of Prague is known for stunning architecture and welcoming people, and is the fifth most- visited city in Europe as a result. The late twentieth century saw the Czech Republic rise as one of the youngest and strongest members of today’s European Union and NATO. Interestingly, the Czech Republic is known for peaceful transitions; from the Velvet Revolution in which they left Communism behind in 1989, to the Velvet Divorce in which they parted ways with Slovakia in 1993. Boasting the lowest unemployment rate in the European Union, the Czech Republic’s stable economy is supported by robust exports, chiefly in the automotive and technology sectors, with close economic ties to Germany and their former countrymen in Slovakia.