Nº 25 Year 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stay with God.Pdf

STAY WITH GOD A Statement in Illusion on Reality Third edition 1990 By Francis Brabazon An Avatar Meher Baba Trust Online Release June 2011 Copyright © Avatar’s Abode Trust 1984 Source and short publication history: This Online Release reproduces the third edition, which is the first illustrated edition (1990), of Stay With God, published by New Humanity Books, Melbourne, Australia. Stay With God was originally published by Edwards and Shwa for Garuda Books, Woombye, Queensland, in 1959, and a second edition was published in 1977 by Meher House Publications, Bombay, India. eBooks at the Avatar Meher Baba Trust Web Site The Avatar Meher Baba Trust’s eBooks aspire to be textually exact though non- facsimile reproductions of published books, journals and articles. With the consent of the copyright holders, these online editions are being made available through the Avatar Meher Baba Trust’s web site, for the research needs of Meher Baba’s lovers and the general public around the world. Again, the eBooks reproduce the text, though not the exact visual likeness, of the original publications. They have been created through a process of scanning the original pages, running these scans through optical character recognition (OCR) software, reflowing the new text, and proofreading it. Except in rare cases where we specify otherwise, the texts that you will find here correspond, page for page, with those of the original publications: in other words, page citations reliably correspond to those of the source books. But in other respects—such as lineation and font—the page designs differ. Our purpose is to provide digital texts that are more readily downloadable and searchable than photo facsimile images of the originals would have been. -

Muslim Saints of South Asia

MUSLIM SAINTS OF SOUTH ASIA This book studies the veneration practices and rituals of the Muslim saints. It outlines the principle trends of the main Sufi orders in India, the profiles and teachings of the famous and less well-known saints, and the development of pilgrimage to their tombs in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. A detailed discussion of the interaction of the Hindu mystic tradition and Sufism shows the polarity between the rigidity of the orthodox and the flexibility of the popular Islam in South Asia. Treating the cult of saints as a universal and all pervading phenomenon embracing the life of the region in all its aspects, the analysis includes politics, social and family life, interpersonal relations, gender problems and national psyche. The author uses a multidimen- sional approach to the subject: a historical, religious and literary analysis of sources is combined with an anthropological study of the rites and rituals of the veneration of the shrines and the description of the architecture of the tombs. Anna Suvorova is Head of Department of Asian Literatures at the Institute of Oriental Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. A recognized scholar in the field of Indo-Islamic culture and liter- ature, she frequently lectures at universities all over the world. She is the author of several books in Russian and English including The Poetics of Urdu Dastaan; The Sources of the New Indian Drama; The Quest for Theatre: the twentieth century drama in India and Pakistan; Nostalgia for Lucknow and Masnawi: a study of Urdu romance. She has also translated several books on pre-modern Urdu prose into Russian. -

Philosophical Affinity Between Tagore and Sufi Poets of Iran

Philosophical Affinity between Tagore and Sufi Poets of Iran Niaz Ahmed Khan Abstract India and Iran have centuries’ old bond of socio-cultural, philosophical and mystical pursuits firmly deep rooted in the socio-ethical lives of both the countries. They have ever been a potential breeding ground for spiritual endeavours and philosophical reflections. With the advent of Islam there upon the genesis and development of Sufi movement in Iran side by side the Bhakti movement here in India brought both the nations close to each other to interact and share their spiritual gains. These two countries produced many luminaries throughout the ages immemorial. Among them Hafiz, Rumi in Iran and Tagore in India outshined their predecessors in their philosophical outlook and humanistic approach. The present article is a humble attempt to trace, find out and correlate the thread of common elements much pertinent to their works. Key Words: Mysticism, humanism and Philosophy شکر شکن شوند همه طوطیان هند زین قند پارسی که به بنگا له می رود All the parrots (poets) of India will be overwhelmed By the sweetness of this sugar candy of Persia that goes to Bengal Some centuries ago a ruler of Bengal once invited Hafiz Shirazi the divine tongued Persian poet of Iran but owing to his advanced age thereupon strenuous journey involved in he could not venture out and just sent a ghazal in response to that containing this famous couplet. Down a trail of centuries later a sun rose from Translation Today 77 Philosophical Affinity between Tagore and Sufi Poets of Iran the eastern horizon of Bengal and gradually soaring high reached his zenith to spread luminosity throughout the world whose poetic attainment name and fame made every Asian country to be proud of and consider him to be their own. -

The Heart of Islamic Philosophy This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Heart OF

The Heart of Islamic Philosophy This page intentionally left blank tHE hEART OF iSLAMIC pHILOSOPHY the quest for self-knowloge in the teachings of afdal al- din kashhani WILLIAM C. CHITTICK OXFORD 2OOI OXFORD Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Sao Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 2001 by William C. Chittick Published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chittick, William C. The heart of Islamic philosophy : the quest for self-knowledge in the teachings of Afdal al-DIn Kashani / William C. Chittick. p. cm. Includes indexes. ISBN 0-19-513913-5 I. Philosophy, Islamic—Iran. 2. Sufism—Iran. 3. Baba Afdal, I3th ce I. Title. 6743.17045 2OOO iSi'.oy—dc2i 00-020628 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper FOR SEYYED HOSSEIN NASR This page intentionally left blank Preface I set out to write this book with two goals in mind—first, to introduce the major themes of Islamic philosophy to those unfamiliar with them, and second, to add Afdal al-DIn KashanI to the list of Muslim philosophers who can be read in English trans- lation. -

Abstract Studying About the Second Part (Al-Bab) Which Comprises 12 Parts, Shows That the Poet's View About Qur’An Is Generalized in 14 Parts

Global Social Sciences Review (GSSR) Vol. IV, No. I (Winter 2019) | Page: 380 – 386 “The Persian Qur’an” - “Hadigatul-hagiga” by Sanayi Ghaznavi 50 I). - Assistant Professor, Department of Urdu, GCU-Lahore, Punjab, Farzana Riaz Pakistan. Email: [email protected] Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Alizada Aygun, Aygun Alizade Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences. Chairperson, Department of Persian, Lahore College for women Faleeha Zahra Kazmi university, Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. The article studies the second part of "Hadigatul- hagiga" work by Sanayi, which is about Qur’an. Abstract Studying about the second part (al-bab) which comprises 12 parts, shows that the poet's view about Qur’an is generalized in 14 parts. If a human wants to wake up from ignorance and turn away from the rebel way, he has to read the Qur’an. To get pleasure from reading the Qur’an one should know the reason why it was revealed. The Qur’an is a candle of Islamic way, the guara of human faith. The Qur’an came down in order to lift people Key Words up. The Qur’an never reveals its secrets to strangers. Sanayi Ghaznavi, “Hadigatul- Therefore, it drapes musk-emitting curtains between itself and http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2019(IV Hagiga”, Persian Literature, Allah, strangers. From the day it was revealed The Qur’an will be protected till the end of the world, and will never lose its Qur’an, Mystica, Sufizm, Human, URL: freshness. The Qur’an has layers. The letters of The Qur’an Book, Islamic Knowledge are its body, and the spirit is its meaning. -

Flowers of Persian Song and Music: the Gulhā Programmes

Flowers of Persian Song and Music The Gulha Programmes Produced by Davoud Pirnia The Gulha weekly radio programmes were produced by Davoud Pirnia (1901-1971) and aired on Iranian radio between 1956 and 1979. These programmes covered the entire history of classical as well as contemporary Persian poetry, giving marvellous expression to the whole gamut of traditional Persian music and poetry. This CD provides a representative sampling of the programmes, and thereby aims to give an overview of the classical music of Persia. The Gulha Programmes The Gulha programmes have been referred to by many scholars of Persian Studies as a veritable encyclopaedia of Persian music and poetry. These programmes are made up of literary commentary with the declamation of poetry, which is sung with musical accompaniment, interspersed with solo musical pieces. For the 23 years that these programmes were broadcast, the most eminent literary critics, famous radio announcers, singers, composers and musicians in Iran were all invited to participate in them. The foremost and best musicians, vocalists, literary critics, poets and announcers performed, so the programmes provide a unique—in fact still the best and most poetically diverse—recorded collection of the classical corpus of Persian music and poetry Davoud Pirnia Husayn Qavtami made in the twentieth century. The programmes were exemplars of excellence in the sphere of music and refined examples of literary expression, making use of a repertoire of over 500 classical and modern Persian poets, setting literary and musical standards that are still looked up to with admiration in Iran today. They marked a watershed in Persian culture, following which music and musicians gained respectability. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY ABDOLI 2001 = ABDOLI , ɊA.: Farhang-e tatbiqi-e tāleši, tāti, āzari . Tehrān 1380/2001. ABDURAXMANOV 1954 = ABDURAXMANOV , R.: Russko-uzbekskij slovar′: 50000 slov; s pril. grammatičeskix tablič russkogo jazyka . Moskva 1954. ɊABDUL QAYYŪM BALOČ 1997 = ɊABDUL QAYYŪM BALOČ : Baločī būmyā . Qoetta 1997. ABRAHAMIAN 1936 = ABRAHAMIAN , R.: Dialectes des israélites de Hamadan et d’Ispahan et dialecte de Baba Tahir . (Dialectologie iranienne). Paris 1936. ABRAMJAN 1965 = ABRAMJAN , R.: Pexlevijsko-persidsko-armjano-russko-anglijskij slo- var′. Erevan 1965. ɊĀDELXĀNI 2000 = ɊĀDELXĀNI , H.: Farhange Āmorei (vāženāme, farhang-e emsāl va kenāyāt va .. ). Jeld-e avval . Arāk 1379/2000. ADIB TUSI 1963–1964 = ADIB TUSI , M. A: ‘Farhang-e loγāt-e bāzyāfte (mostadarak)’, Našrie- ye dāneškade-ye adabiāt-e Tabriz , 15/3, 15/4 (1342/1963); 16/1, 16/2, 16/3 (1343/1964). ADIB TUSI 1992 = ADIB TUSI , M. A.: ‘Namune-ye čand az loγāt-e āzari’, in AFŠĀR , I. (ed.), Zabān-e fārsi dar Āzerbāi ǐān II. Az neveštehā-ye dānešmandān va zabānšenāsān . Tehrān 1371/1992, 235–361 [first publ. in Našrie-ye Dāneškade-ye adabiāt-e Tabriz 8–9 (1335/1956 − 1336/1957)]. AFΓĀNI NEVIS 1956 = AFΓĀNI NEVIS , ɊA.: Loγāt-e Ɋ āmiāne-ye fārsi-ye Afγānistān . Afγā- nistān 1335/1956. AFŠĀR 1989 = AFŠĀR , I.: Vāženāme-ye yazdi . (Selsele-ye matun-e va tahqiqāt az entešārāt-e ǐedāgāne-ye Farhang-e Irān Zamin 35 – Gan ǐine-ye Ho- sein-e Bašārat barā-ye pežuheš dar farhang va tārix-e Yazd 2) Tehrān 1368/1989. AFŠĀR SISTĀNI 1986 = AFŠĀR SISTĀNI , I.: Vāženāme-ye sistāni . (Bonyād-e Nišāpur 13). Tehrān 1365/1986. -

GHAREHGOZLOU, BAHAREH, Ph.D., August 2018 TRANSLATION STUDIES

GHAREHGOZLOU, BAHAREH, Ph.D., August 2018 TRANSLATION STUDIES A STUDY OF PERSIAN-ENGLISH LITERARY TRANSLATION FLOWS: TEXTS AND PARATEXTS IN THREE HISTORICAL CONTEXTS (261 PP.) Dissertation Advisor: Françoise Massardier-Kenney This dissertation addresses the need to expand translation scholarship through the inclusion of research into different translation traditions and histories (D’hulst 2001: 5; Bandia 2006; Tymoczko 2006: 15; Baker 2009: 1); the importance of compiling bibliographies of translations in a variety of translation traditions (Pym 1998: 42; D’hulst 2010: 400); and the need for empirical studies on the functional aspects of (translation) paratexts (Genette 1997: 12–15). It provides a digital bibliography that documents what works of Persian literature were translated into English, by whom, where, and when, and explores how these translations were presented to Anglophone readers across three historical periods—1925–1941, 1942–1979, and 1980–2015— marked by important socio-political events in the contemporary history of Iran and the country’s shifting relations with the Anglophone West. Through a methodical search in the library of congress catalogued in OCLC WorldCat, a bibliographical database including 863 editions of Persian-English literary translations along with their relevant metadata—titles in Persian, authors, translators, publishers, and dates and places of publication—was compiled and, through a quantitative analysis of this bibliographical data over time, patterns of translation publication across the given periods -

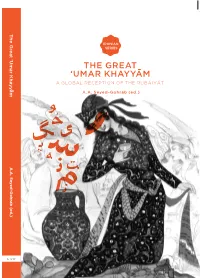

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

Transcendent Philosophy Journal Is an Academic Seyed G

Editor in Cheief Transcendent Philosophy Journal is an academic Seyed G. Safavi peer-reviewed journal published by the London London Academy of Iranian Studies, UK Academy of Iranian Studies (LAIS) and aims to create a dialogue between Eastern, Western and Asistant Editor in Chief Islamic Philosophy and Mysticism is published in Seyed Sadreddin Safavi December. Contributions to Transcendent London Academy of Iranian Studies Philosophy do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial board or the London Academy of Book Review Editor Iranian Studies. Sajjad H. Rizvi Exeter University, UK Contributors are invited to submit papers on the following topics: Comparative studies on Islamic, Editorial Board Eastern and Western schools of Philosophy, Philosophical issues in history of Philosophy, G. A‟awani, Iranian Institue of Philosophy, Iran Issues in contemporary Philosophy, Epistemology, A. Acikgenc, Fatih University, Turkey Philosophy of mind and cognitive science, M. Araki, Islamic Centre England, UK Philosophy of science (physics, mathematics, biology, psychology, etc), Logic and philosophical S. Chan, SOAS University of London, UK logic, Philosophy of language, Ethics and moral W. Chittick, State University of New York, USA philosophy, Theology and philosophy of religion, R. Davari, Tehran University, Iran Sufism and mysticism, Eschatology, Political Philosophy, Philosophy of Art and Metaphysics. G. Dinani, Tehran University, Iran P.S. Fosl, Transylvania University, USA The mailing address of the Transcendent M. Khamenei, SIPRIn, Iran Philosophy is: Dr S.G. Safavi B. Kuspinar, McGill University, Canada Journal of Transcendent Philosophy H. Landolt, McGill University, Canada 121 Royal Langford O. Leaman, University of Kentucky, USA 2 Greville Road Y. Michot, Hartford Seminary, London NW6 5HT Macdonald Center, USA UK M. -

From Qays to Majnun: the Evolution of a Legend Fromʿudhri Roots to Sufi Allegory

Alasdair Watson From Qays to Majnun: the evolution of a legend fromʿUdhri roots to Sufi allegory TOWARDS THE END of the 12th century of the common era,1 the Persian poet Abu Muhammad Nizami of Ganjah, whose proper name was Ilyas son of Yusuf son of Zaki, composed the third masnavi or long poem in rhymed couplets of his Khamsa (‘Quintet’) also known as the Panj Ganj (‘Five Treasures’). This masnavi, entitled Layli u Majnun, was apparently written in the space of four months; quite a feat considering it is composed of more than 4,000 verses.2 It was dedicated to the Sharvan Shah Akhsitan I (d. 1197), ruler of Sharvan,3 the region in the eastern Caucasus where Nizami lived. The Shah had sent a letter to Nizami requesting that he compose a poem ‘like a hidden pearl’ of the love story of Majnun and Layla and dedicate it to him, and, like the Shah’s own lineage which was said to go back to the last of the pre-Islamic Sasanian kings, the poem should be just as long.4 Nizami found himself disconcerted; he did not have the courage to disobey the king’s letter but could not see a way to retell the story in full, until his son Muhammad put a manuscript of the story of Layla and Majnun in his father’s hand and consoled him and encouraged him to write the romance.5 Although it reached its most perfect form in Nizami’s version and is celebrated in several world literatures, the story of Layla and Majnun began in the Arabian desert of the 7th century of the common era with the tragic, ʿUdhri love story of Qays ibn al- Mulawwah and his beloved Layla. -

The Fascinator of South Asian Persian Poets

South Asian Studies A Research Journal of South Asian Studies Vol. 24, No. 1, January 2009, pp. 152-163 Faghani, the Fascinator of South Asian Persian Poets Muhammad Nasir University of the Punjab, Lahore ABSTRACT The impact of Persian language and literature on South Asia in general and Indo-Pak subcontinent in particular is unparalleled to any other language or literature. The cultural traditions, historical bequest, philosophical birthright, religious inheritance and literary heritage of the Muslims of South Asia have been preserved in Persian. Amazingly, this so- called foreign language remained the official and court language of South Asia during the Muslim period and even the Sikh regime followed the course. The classical Persian poetry is divided into three foremost literary styles, namely Khorasani, Iraqi and Indian. Baba Faghani, the founder and innovator of the Indian style has inspired the South Asian Persian poets to a great deal. His impact on every single poet of Indian style is significant and unparallel. More importantly, he was much highly esteemed in India than in his own country. In this article, poetry of Baba Faghani, the forgotten and neglected fascinator of South Asian Persian poets has been introduced and critically evaluated in the light of some renowned literary criticism and narration. The Persian literature (Persian Literature. (n.d.). In Encyclopædia Britannica online. Retrieved March 16, 2008, from http://www.britannica.com) is privileged to have had sheer brilliance over the past thousand years. The history of world literature is left over and curtailed without extending a lions share to Persian poetry. In addition to that, in the same way, its great impact on Persian literature of South Asia is certainly high-flying.